Ken Burns' 'Country Music': Waylon Jennings, Emmylou Harris and 'I Will Always Love You'

Disagreeing over what is or isn't country music? That's nothing new. And it wasn't new 50 years ago.

Still, in the seventh episode of Ken Burns' "Country Music" — titled "Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?" — that battle reaches a new level.

"In the 1970s, defining country music would be debated as never before," Peter Coyote narrates. "But that argument would spark one of its most vibrant eras, making room for new voices and new attitudes."

Chief among those voices are Waylon Jennings, Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris and Hank Williams Jr., along with the continuing saga of George Jones and Tammy Wynette.

Other highlights include the arrival of Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark and Rodney Crowell; Marty Stuart's life-changing performance with Lester Flatt at age 13; the final Opry at The Ryman; Willie Nelson's triumph as an outlaw; and Rosanne Cash stepping out from her father's shadow.

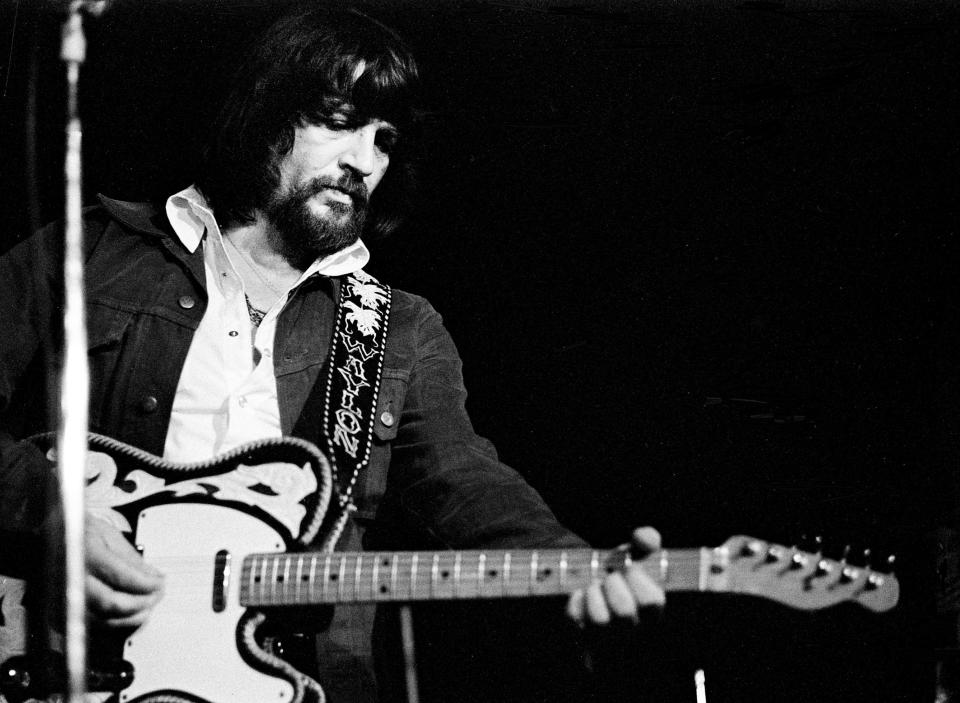

Waylon Jennings

"His voice is what tore me up … just like the way Hank Williams tore me up. He could sing songs that I can't." – Kris Kristofferson

Country music was part of Jennings' life for as long as he could remember — literally. Viewers learn that his earliest memory was of his father hooking up the family radio to the pickup truck's battery and tuning into the Grand Ole Opry.

"In my house, it was the bible on the table, the flag on the walls, and Bill Monroe's picture beside it," he once said.

His early performing experience included a stint in Buddy Holly's band, and he was almost on the plane that crashed and killed Holly, Richie Valens and The Big Bopper.

Despite the warnings from his friend Willie Nelson, Jennings made the move from Texas to Nashville, where he made a string of albums with Chet Atkins. They were modest successes, but the sound wasn't true to Jennings.

"They were good, smooth records, but I was rougher than a … corncob. All the damn sand I swallowed in Texas is in my singing."

"I was the black sheep of Nashville. They thought I was a troublemaker."

In 1972, Jennings signed a new deal with RCA Victor — one that "broke all the prevailing Nashville rules," Coyote narrates. He was able to choose his own material and use his own band in the studio, recording at all hours at Tompall Glaser's "Hillbilly Central."

His status as an outside, independent force in country music was exemplified in his 1975 smash "Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way."

Hank Williams Jr.

As Jennings' song suggests, Williams' shadow still hung over the country world, more than 20 years after his death.

"No one felt it more keenly than his only son," Coyote says.

Hank Williams Jr. was 3 years old when his father died, and has few actual memories of him. Under the guidance of his mother, Audrey Williams, he began performing his dad's songs at age 8, and made his Opry debut at 11.

He felt incredible pressure to fill his father's shoes and mimic his every move — Johnny Cash even urged Audrey to "loosen up" and "let him be Hank Williams Jr. for a while."

Once he turned 18, Williams dropped his mother as his manager and set out to carve his own path.

"Daddy don't need me to promote him," Jr. says in his "Country Music" interview. "How dumb can you be?"

He recorded his Southern rock-inspired breakthrough, "Hank Williams Jr. and Friends" in 1975. Another seismic event occurred that year, when he barely survived a 500-foot fall in the Montana mountains.

After 16 months of recovery and nine surgeries, he reemerged. When he reached 29 — the same age his father was when he died — Williams released "Family Tradition," beginning a string of 21 gold records.

Dolly Parton tells Porter Wagoner, 'I Will Always Love You'

In 1974, Parton had been performing on "The Porter Wagoner Show" for seven years, and for that entire run, Wagoner had "tight control over her career," Coyote narrates.

"I signed the checks, so we did things my way," he once said.

But he also encouraged Parton's undeniable talent as a songwriter, which led to her recording her self-penned classics "Coat of Many Colors" and "Jolene." Soon enough, she'd racked up five No.1 solo hits, all of them self-written.

"Porter dreamed of me staying with his show forever," Parton said. "And I dreamed of having my own show. I wrote more and more songs, and dreamed bigger and bigger dreams."

When Parton planned to part ways with Wagoner after seven years, he wasn't pleased. Parton said he even threatened to sue her.

"I thought, 'He's not gonna listen to me, because I've said it over and over.' And so I thought, 'Do what you do best. Just write a song.' So I wrote the song, took it back in the next day and said, 'Porter, sit down. There's something I have to sing to you.'"

The song was "I Will Always Love You," and it brought Wagoner to tears.

"He said, 'That's the best thing you ever wrote. OK, you can go, but only if I can produce that record.'"

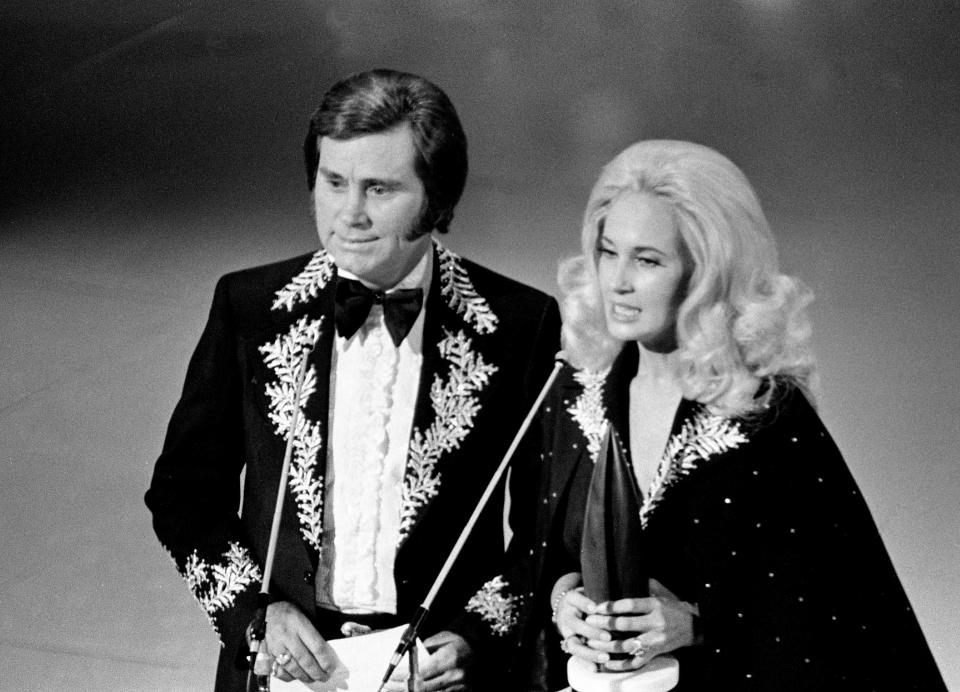

George Jones and Tammy Wynette

"No couple captivated audiences and headlines" more than Jones and Wynette, Coyote narrates. That wasn't only due to their run of incredible hit duets, but a marriage that was "never tranquil," thanks her volatile personality and his out-of-control drinking.

"George is one of those people who can't tolerate happiness," Wynette later said. "If everything is right, there is something in him that makes him destroy it, and destroy me with it."

Wynette first filed for divorce in 1973, but they reconciled long enough to record "We're Gonna Hold On," which played as autobiography as it rose to No. 1. The couple ultimately divorced in 1975.

That didn't stop them from recording "one more duets album" in 1976. (In fact, the pair would reunite for two more albums in 1980 and 1995.)

The title track, "Golden Ring," was another chart-topper.

According to "Country Music," it was playing on Wynette's car radio as she was on her way to marry her fourth husband. And it was still on the charts when that marriage ended 44 days later.

Emmylou Harris

"Except for Johnny Cash, I couldn't be fooled with country music," Harris recalls. "Folk music was what really spoke to me."

The Alabama native, in fact, didn't start on the path to Nashville until she went to Los Angeles to record with Gram Parsons. She became a "huge country music convert."

"I finally felt I had found where I was supposed to be as a singer."

After Parsons died of an overdose in 1973, Harris wanted to make a country album, "almost in memory of Gram."

Two years later, she emerged with two brilliant albums, "Pieces of the Sky" and "Elite Hotel." She surrounded herself with stellar musicians — including Rodney Crowell — in a group dubbed The Hot Band, and became a critical darling. Rolling Stone called her "country without the corn."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Ken Burns' 'Country Music': Waylon Jennings and Emmylou Harris arrive