Kate Bush Steps Out of the Pages of James Joyce and into The Sensual World

The post Kate Bush Steps Out of the Pages of James Joyce and into The Sensual World appeared first on Consequence of Sound.

Music and literature have a long history of affiliation. From the ancient Greek poet Sappho, whose poems were set to music and performed, to the Italian madrigals of the Italian Renaissance (often based on Petrarch’s sonnets), which would be sung communally in people’s homes, to the lyrical masterminds of rap like Biggie, Lauryn Hill, and Jay-Z, poets have often found a medium in song. Kendrick Lamar is already inspiring college courses and theses. You could write a book on Joanna Newsom’s lyrics alone, not to mention the music itself. And this summer, we said goodbye to one of the great contemporary poet-musicians, David Berman — known for his work with the band Silver Jews, his poetry collection Actual Air, and, most recently, his great album as Purple Mountains.

Kate Bush is one of those fascinating songwriters not only interested in making literature through music, but also in making music about literature — consciously alluding to and complicating literary and literary-critical traditions, a tendency perhaps most pronounced on her masterful album The Sensual World, which turns 30 this year. There’s an art to the implied commentary of juxtaposition and allusion. Bob Dylan was known for it — name-dropping Eliot, comparing his own tempestuous relationship to that of the French poets Verlaine and Rimbaud, and then there was some Italian poet from the 13th century, considered by some to be Petrarch (who technically lived in the 14th century) or Dante. (Side note: Dylan once claimed in an interview it was “Plutarch,” the Greek writer of antiquity. He might have meant Petrarch — or he might have just been fucking with the interviewer, as he’s been known to do.)

These kinds of allusions can be a way for a musician to position themselves, not only within a musical canon but within a literary canon as well, Dylan’s recent Nobel Prize in literature being an institutional confirmation of this, as well as an institutional confirmation of the intertwining histories of the two genres. We see the same tendency in The Doors’ decision to name their band after Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, which described his experience on mescaline, itself a reference to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by the English poet William Blake. Jim Morrison was, of course, a poet himself, a reader of William Blake and the Beats.

But unlike The Doors or Bob Dylan, Kate Bush went beyond allusion, entering the territory of interpretation and criticism in her music. It’s been 30 years since the release of her masterful record The Sensual World, an album that likewise uses song as a vehicle for exploring and commenting on literature — in this case James Joyce’s Ulysses, as well as (less prominently) William Blake. This was not without precedent for Bush, whose breakout hit, “Wuthering Heights”, surely one of the strangest songs to ever hit No. 1 on the UK charts, evoked the tormented sorrow of Emily Brontë’s novel of the same name. Even if you haven’t read the novel, the lines “Heathcliff, it’s me, Cathy/ Come home, I’m so cold” will no doubt still strike a chord due to Bush’s acrobatic phrasing and her melody, which constantly winds back on itself.

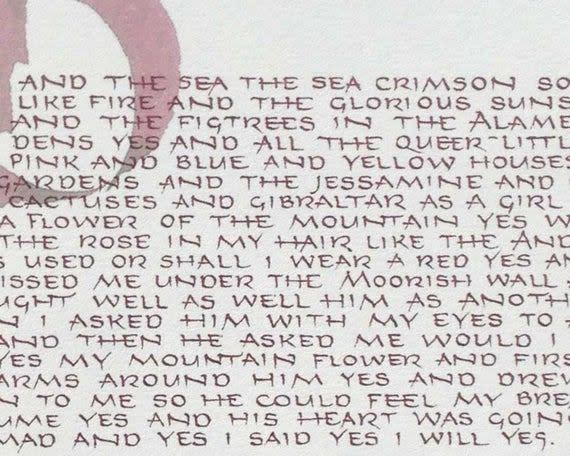

For the opening, title track of The Sensual World, Bush had originally planned to take an excerpt of Molly Bloom’s final soliloquy from James Joyce’s Ulysses — a continuous, un-punctuated mass of text — and put it to music. However, unable to get the rights from the Joyce estate, she wrote her own version of Molly Bloom’s speech, incorporating elements of the original text while making something that was her own. (In 2011, the Joyce estate actually did grant Bush’s request, and you can hear another version of the song, which quotes Ulysses verbatim, on the 2011 record Director’s Cut.) The song unfolds from Bush’s words. It is rhythmically punctuated by Bush singing, “Mmm, yes,” evoking Molly Bloom’s repetition of yes near the end of the book. Adorning these words, Davy Spillane plays the uilleann pipes, a traditional Irish instrument, the melody adapted from a Macedonian dance. By recontextualizing language in song, Bush gives form to a piece of text by Joyce that is, by its nature, formless (insofar as it lacks punctuation). Bush characterizes this form in terms of moving from text to the real world: “Stepping out of the page into the sensual world.”

The lack of punctuation in the final chapter of Ulysses has led many literary critics to attribute to Molly Bloom’s thoughts a kind of “flow.” The English academic Derek Attridge, however, has taken issue with this characterization. Attridge points out that many critics’ comments on the unconventional nature of Molly Bloom’s language, to which this sense of “flow” is attributed, is based not in her language itself, but in its presentation. As he puts it, “Once the missing punctuation and other typographical absences have been made good, the language of this episode is relatively conventional.” For example, add conventional punctuation to “God of heaven there’s nothing like nature the wild mountains then the sea and the waves rushing then the beautiful country with the fields of oats and wheat and all kinds of things,” and you have: “God of heaven, there’s nothing like nature — the wild mountains, then the sea and the waves rushing, then the beautiful country with the fields of oats and wheat and all kinds of things.” Definitely a long sentence, but not a particularly atypical one. Attridge effectively summarizes the phenomenon at work here: “We have to conclude, then, that the sense of an unstoppable onward movement ignoring all conventional limits is derived from the language, not as it supposedly takes shape in the human brain, but as it is presented (unknown to Molly) on the page.”

The fact that this is unknown to Molly is crucial to Bush’s project in bringing Molly off the page. As a speaker, Molly Bloom does not have control over her own lack of cohesion. The language itself is relatively conventional. It is Joyce who renders it unstable by leaving out punctuation. Bush, in taking Joyce’s words, initially would have done for Joyce what Joyce did for Molly Bloom, within the fiction of the text — that is, appropriate his words unbeknownst to him and place them in a new context. However, as Bush was unable to obtain the rights from Joyce’s estate, she took on the role of both author and framer of the words. In doing so, she lends additional form to Molly Bloom’s thoughts, through her own appropriation of Joyce’s/Molly Bloom’s language. Though the form of music is different from that of literature, Bush does punctuate the song through the rhythm of “Mmm, yes.” The vocals that open the song are highly percussive, as Bush spits each word out like a metronome: “Then—I’d—ta—ken—the kiss of—seedcake—back from his mouth.” Prefigured by church-bells, the verses unfold, accompanied by the woozy dance of uillean pipes.

Direct quotes from Ulysses like the reference to the seedcake and the “flower of the mountain” stand alongside Bush’s own commentary, which adds clarity to her own project: “Stepping out of the page into the sensual world.” With these words, Bush acknowledges her own stepping away from Joyce’s text. Her allusion to Blake in this song — “And my arrows of desire rewrite the speech” – likewise evokes Bush’s rewriting of the soliloquy. In the context of Attridge’s argument, Bush’s project of taking Molly Bloom off of the page is an act of liberation, perhaps, giving Molly cogency and agency she didn’t have before. At the same time, Bush, in giving form to Molly Bloom’s thoughts, and, much like Joyce, making her own commentary, is not so much liberating Molly Bloom’s speech as she is recontextualizing it. In doing so, she demonstrates the way in which form and lack of form both are impositions on an imagined speaker.

This game of power, control, creation, and desire carries through the rest of the album. There’s the dramatic irony of “Heads We’re Dancing,” the tenuous dance of flirtation, evil, and political power reflected in Mick Karn’s restless, anxious bass. “Between a Man and a Woman” describes the balance of power within a relationship as a pendulum swinging. On “Never Be Mine,” the speaker takes ownership of her own desire, “This is where I want to be/ This is what I need.” Bush’s reverbed vocals, alongside the Bulgarian vocal ensemble Trio Bulgarka, give the statement the force of a declaration.

By 1989, Kate Bush had already made a string of classics — including Hounds of Love, The Dreaming, and The Kick Inside — but The Sensual World, in particular the multi-layered, allusive title track, marked another ambitious statement of artistic and critical intent in an already storied career. On The Sensual World, Bush explores, through her engagement with Joyce’s text, the power of love, texts, and art in general — their capacity for both liberation and confinement.

Kate Bush Steps Out of the Pages of James Joyce and into The Sensual World

Matt Melis

Popular Posts