Jumping Jupiter! How did all our schools get planetariums? NJ has more than a dozen

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Scientists playing God."

That's a phrase you've heard before. In connection with Dr. Oppenheimer, perhaps — or Dr. Frankenstein. But 100 years ago, this month, came the most stunning case of all.

On Oct. 21, 1923, engineers at the Carl Zeiss firm in Jena, Germany, created the universe.

"The planetarium is really one of the most amazing things," said astronomer Gary Swangin, past director of the Dreyfuss Planetarium at the Newark Museum, and the Panther Academy Planetarium in Paterson.

"The first time I went, I couldn't believe there was such a machine, that could recreate the universe, night or day, at different times of the year," Swangin said. "It was awesome. Magical."

They're everywhere

Today, the planetarium is commonplace. The cliché school field trip. New Jersey alone has more than a dozen — including several in local schools (Fair Lawn, Northern Highlands Regional High School, Glenfield Middle School in Montclair), and in big cities (Newark, Trenton). The one at the Liberty Science Center in Jersey City is the largest in the western hemisphere.

But when the first of these star theaters was officially demonstrated, 100 years ago, people were gobsmacked. The gasp — the "ahhhhhh!" — that echoed around the chamber, as the stars came out indoors, was almost religious.

"German sources speak about the 'Ah' — maybe in English, 'Wow' — that came from the audience when the projector was switched on," said Volkmar Schorcht of Carl Zeiss AG, which still makes these intricate star machines (the Panther Academy Planetarium, and the Novins Planetarium at Ocean County College in Toms River, both have Zeiss instruments).

"It is a school, a theater, a cinema in one; a schoolroom under the vault of heaven, a drama with the celestial bodies as actors," gushed professor Bengt Strömgren of the Copenhagen Observatory.

But the planetarium is not only amazing in itself. It was the culmination of an amazing movement — an attempt to build world peace through science education.

At its center was the Deutsches Museum von Meisterwerken der Naturwissenschaft und Technik (the German Museum of Masterworks of Science and Technology) in Munich, which opened to the public on May 2, 1925. The star attraction was the planetarium. The world's first.

"The enthusiasm started with the sight of the starry sky," Schorcht said.

What the times demand

It was with some urgency that the Deutsches Museum, and other 1920s "museums of the peaceful arts," came into being.

The world had just been through hell. Upwards of 20 million people had been killed in the Great War, with the aid of terrifying new technologies: tanks, planes, mustard gas. In peace, the new age of the machine was ominous. People felt alienated. They no longer seemed to understand how the world worked, or what their neighbors did in it. Everywhere people were asking: Would the machines save us, or destroy us?

"The processes of production that underlie the civilization of today are hidden behind factory walls," complained educator Charles R. Richards in his influential 1925 book "The Industrial Museum." "Little is known about these operations by the growing boy and girl."

The answer was museums. Showcases of science and industry. Places that could demonstrate how technology worked, and how all professions — all people — were connected.

The most spectacular of these, the Deutsches Museum, had been founded as early as 1903. But its new headquarters, which opened in Munich in 1925, was a Disneyland of mechanical marvels. Kids could see a 20-foot cutaway model ocean liner with working engines, or walk through a realistic coal mine whose floors were believably soggy. They could perform their own "experiments" by pushing buttons and turning cranks.

But what, wondered the museum's visionary founder, Dr. Oskar von Miller, to do about an astronomy exhibit?

Artificial sky

Clearly, it had to be something sensational. The teaching tools already out there — celestial globes, the clockwork "orrery" models of the solar system — seemed tame.

What was needed was an artificial sky.

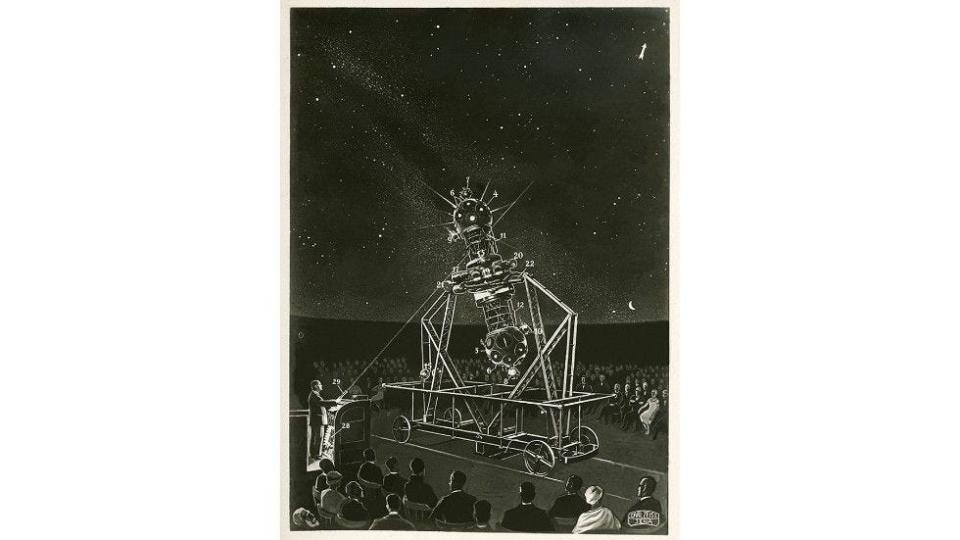

For a while, the Zeiss optical company, commissioned by von Miller to develop the new attraction, toyed with the idea of a giant, walk-in globe. "Stars" would be created by tiny holes in the surface, lit from outside. But this was the age of the motion picture. Why not, said Zeiss engineers Walther Bauersfeld and Rudolf Straubel, just reverse this idea — and project images of stars onto the sphere? Perhaps, even, onto a dome...?

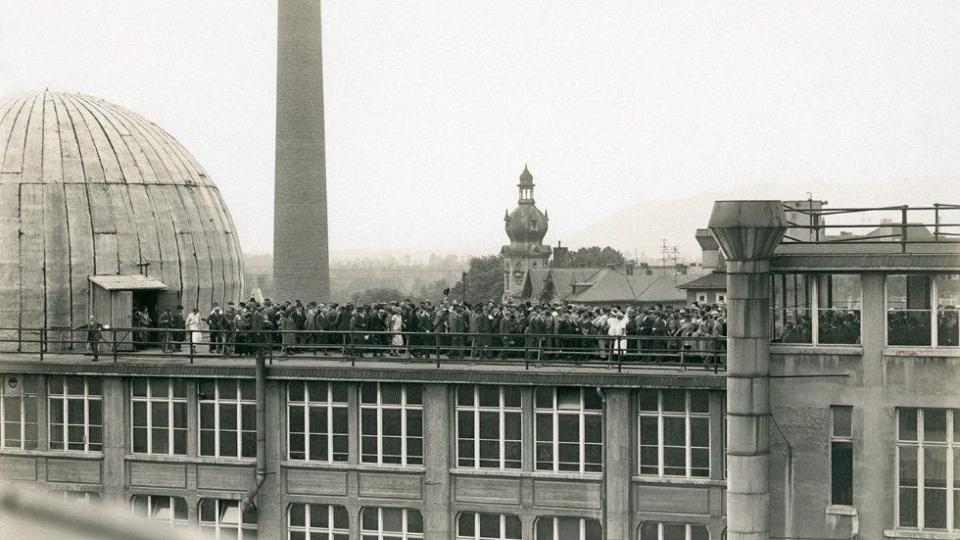

Word soon got out that something extraordinary was happening on the roof of the Zeiss plant in Jena, Germany.

"From early morning till late at night a constant stream of eager visitors, mostly students from distant parts of Germany, jostle one another for places in the elevator going up to the roof of the factory where the planetarium has been erected," read one account in Scientific American.

What they saw left them dumbstruck.

The entire universe, created by machine! Man, like a god, working the controls! Planets, stars and galaxies whizzing by; time speeding up, slowing down, reversing. "The Wonder of Jena," people called it. "Ten years came and went in one minute," marveled Eric Keyser, a United News Staff correspondent. "Stars chased like swarming gnats. The sun looped across the domed sky as though flung from a cannon."

Allow us to demonstrate...

The machine was first officially demonstrated to trustees at Munich's still-unfinished Deutsches Museum on the Isar River, on Oct 21, 1923. Two years later, in May 1925, it opened to the public. Both times, the response was electrifying.

Throngs lined up in front of the world's first geodesic dome — decades before Buckminster Fuller — to see the weird contraption that could show the drama of the heavens.

Germany went planetarium-crazy. A dozen more went up in the 1920s; they became big-time entertainment to compete with the movie theater and the cabaret. "They vie in popularity with films in which Charlie Chaplin and Emil Jannings appear," wrote Waldemar Kaempffert in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

In America, philanthropists competed to see who would fund the first U.S. planetarium. So did hucksters and showmen.

Serious purpose

One wanted a projector for his nightclub. Another wanted one for his excursion boat. A Coney Island entrepreneur wanted a planetarium as an amusement park attraction. Zeiss wasn't having it. "Coney is too frivolous for us," a Zeiss engineer told the Brooklyn Eagle.

To Zeiss, to "industrial museum" advocates like von Miller, the planetarium was serious business. Education was the goal. And with it — maybe — wisdom. "Let [each man] view the heavens one hour each day, and wars on earth will cease," the American astronomer James Hartness had said.

History had other plans.

By the early 1930s, Deutsches Museum director Oskar von Miller was getting pressure to toe the Nazi line. When he resisted, he was forced out, and in 1933 a more pliant director was put in his place. Straubel, one of the two inventors of the planetarium, was booted from Zeiss because of his unacceptable marriage. His Jewish wife later killed herself.

At the museum, new exhibits began to showcase Hitler's achievements in car and plane manufacture; the Fuehrer himself paid a visit in April 1935. In 1937, the Deutsches Museum — the citadel of enlightenment, and the birthplace of the planetarium — opened an exhibit called "The Eternal Jew."

Meanwhile, in America...

But the planetarium idea had spread. By the mid-1930s, America had several. Including one at Philadelphia's Franklin Institute, an "industrial museum" that was a virtual duplicate of the one in Munich — complete with do-it-yourself science experiments.

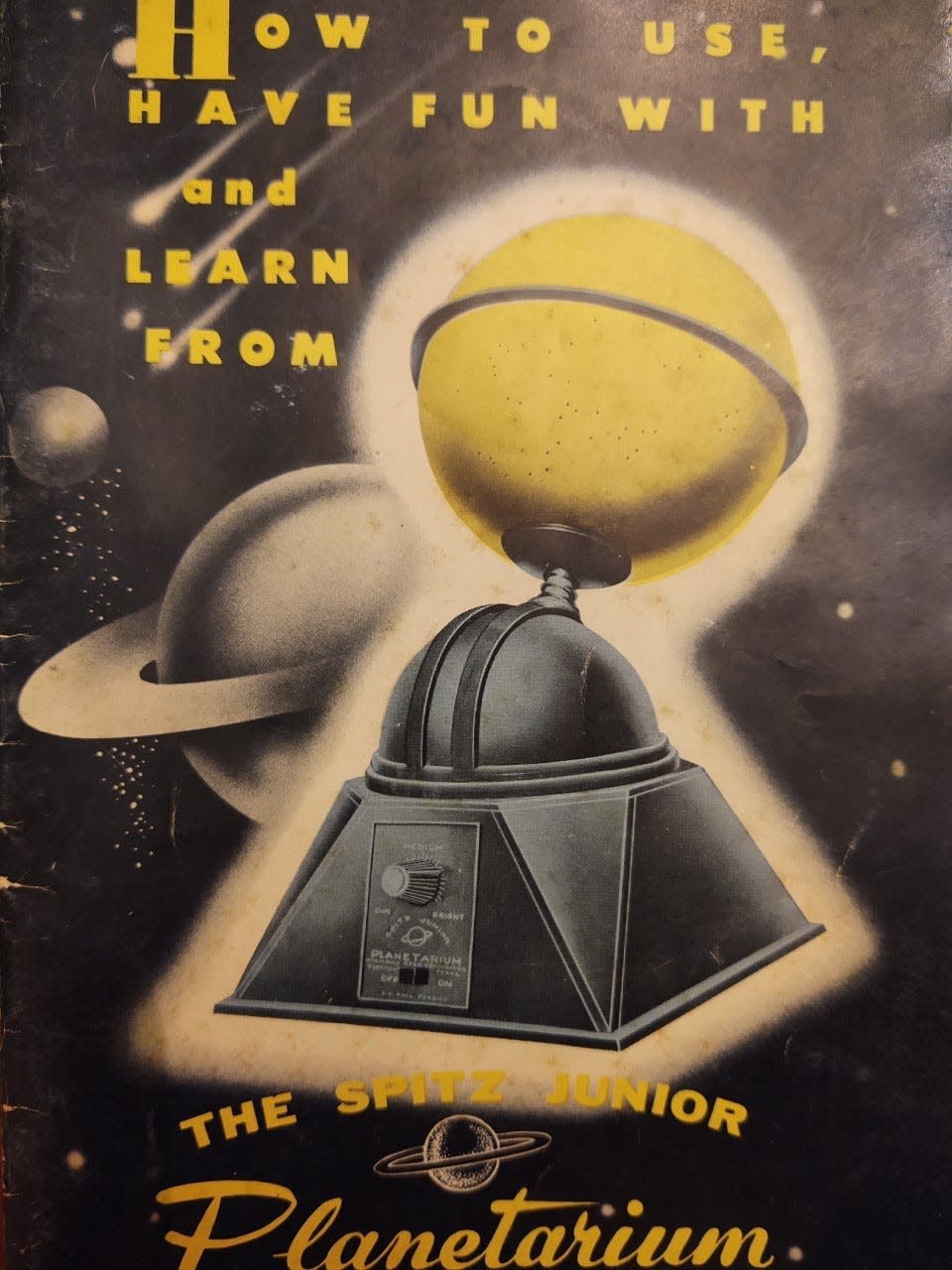

On the staff was an eccentric genius named Armand Spitz. He loved Philadelphia's planetarium, and didn't see why every town shouldn't have one — apart from the minor detail that the Zeiss machine had, in 1937, a $128,000 price tag. He began to tinker with his own low-cost projector — first by poking holes in a soap can, then by slapping together, in 1947, a simplified device called the "Model A" that sold for $500.

Churches, schools, small museums bought them. In 1954, a $15 toy projector, the "Spitz Junior," became the year's Christmas bestseller. Then in 1957, came Sputnik — and panic. America was falling behind! How were kids going to learn about science?

In 1958 the National Defense Education Act, signed by President Dwight Eisenhower, provided $70 million a year in federal funds for public school science education. Spitz — a terrific salesman, the Harold Hill of astronomy — had a pitch. Why not, he told school boards, use that funding for a planetarium?

Which is why there are planetariums, today, at Fair Lawn High School (1960) Northern Highlands in Allendale (1965), Princeton Day School (1967), Jonas Salk Middle School in Old Bridge (1968), and other New Jersey institutions. More than a thousand projectors were sold in the U.S. by Spitz alone; competitors probably doubled that number.

Though not all the schools knew what to do with them when they got them.

Sharing space

"The original planetarium was on wheels, on the stage of the school," said Anthony Villano, former instructor at the Fair Lawn planetarium, first located in one of the district's junior high schools. Later it was moved to the high school.

"They tucked it off into the corner, and when they wanted to do lessons, they would wheel out the console, wheel the dome out," he said. "The dome was suspended on a crane. When they wanted to do stage shows, they would push it off to the side somehow."

It was the 1960s — the space age, the era of American-Soviet rivalry. Clearly, all those "museums of the peaceful arts" had not helped people understand each other. In that respect, the grand 1920s experiment had been a failure.

Yet the planetarium continued to fascinate. As it does to this day. When the lights come down and the stars appear, the kids are still going "Ahhhhhhh!"

"They get the biggest kick out of it," Villano said.

Meanwhile, Fair Lawn provides its own unique bookend to the planetarium story.

When, in the 1980s, their Spitz A2 model was replaced with a more sophisticated Spitz A3P, the original projector found a new home. In Jena Germany, of all places — birthplace of the planetarium, 100 years ago.

"The Zeiss company bought it," Villano said. "They put it in their museum of optical history. As an example of an early Spitz model."

Go...

Alice and Leonard Dreyfuss Planetarium, 49 Washington St., Newark. newarkmuseumart.org

Longo Planetarium, County College of Morris, 214 Center Grove Rd. Randolph. ccm.edu

Ric and Jean Edelman Planetarium, Rowan University, 201 Mullica Hill Road, Glassboro. rowan.edu

Raritan Valley Community College Planetarium, 118 Lamington Road, Branchburg. raritanval.edu

New Jersey State Museum Planetarium, 205 W. State Street, Trenton, nj,gov

Jennifer Chalsty Planetarium, Liberty State Park, 222 Jersey City Boulevard, Jersey City. lsc.org

Robert J. Novins Planetarium, Ocean County College, 1 College Drive, Toms River. ocean.edu

Hayden Planetarium, Rose Center for Earth and Space, American Museum of Natural History, 81st Street between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue, New York. amnh.org

Fels Planetarium, Franklin Institute, 222 N 20th St, Philadelphia. fi.edu

Hudson River Museum, 511 Warburton Ave., Yonkers. hrm.org

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NJ planetariums: How did North Jersey schools get locations?