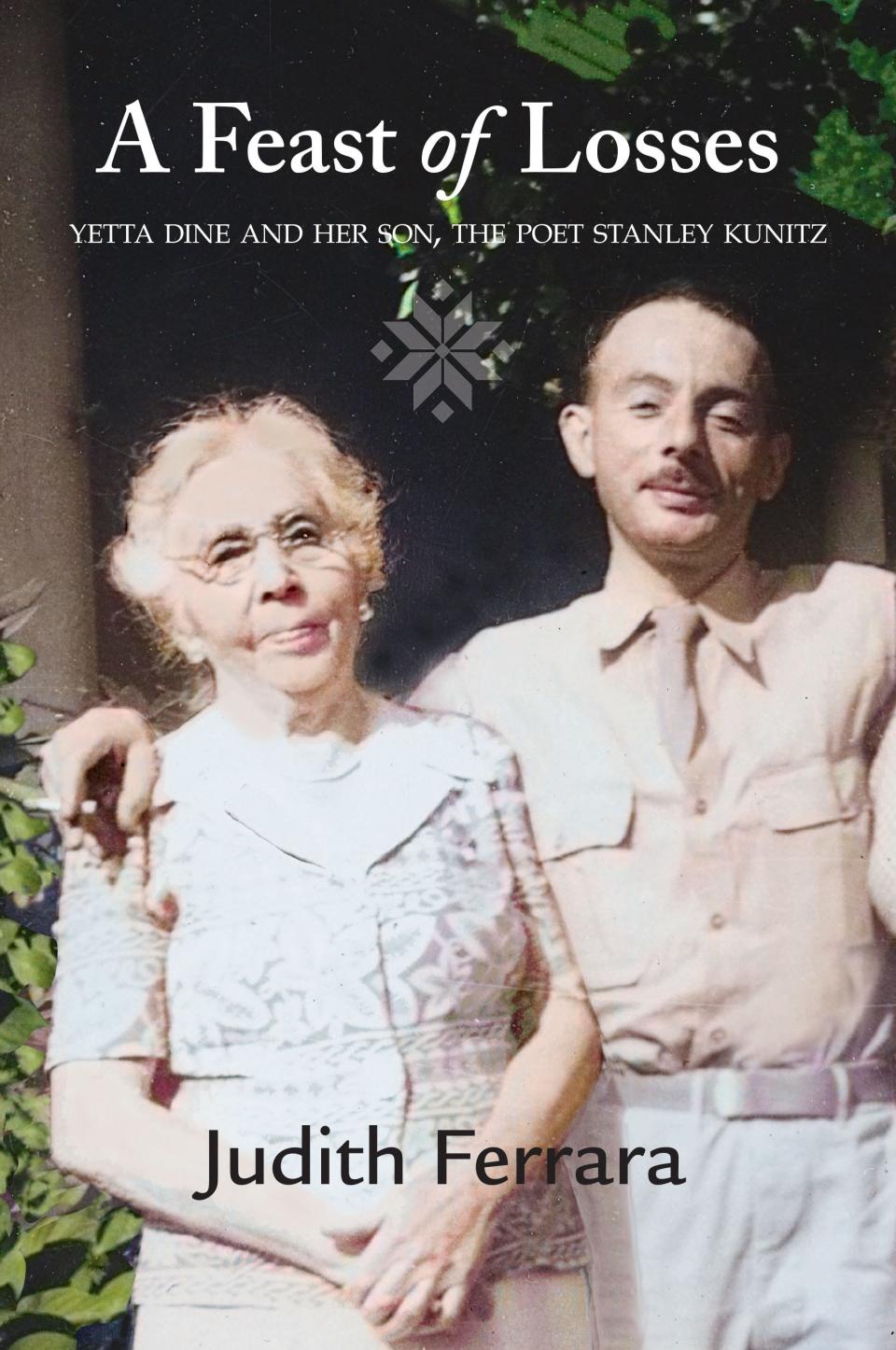

Judith Ferrara uncovers new perspectives on Stanley Kunitz's mother in 'A Feast of Losses'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In his award-winning poetry, Worcester's Stanley Kunitz sometimes sought the elusive father, unknown or dead, a haunting figure. His mother, however, is present in some poems, but not in an affectionately recalled or depicted way.

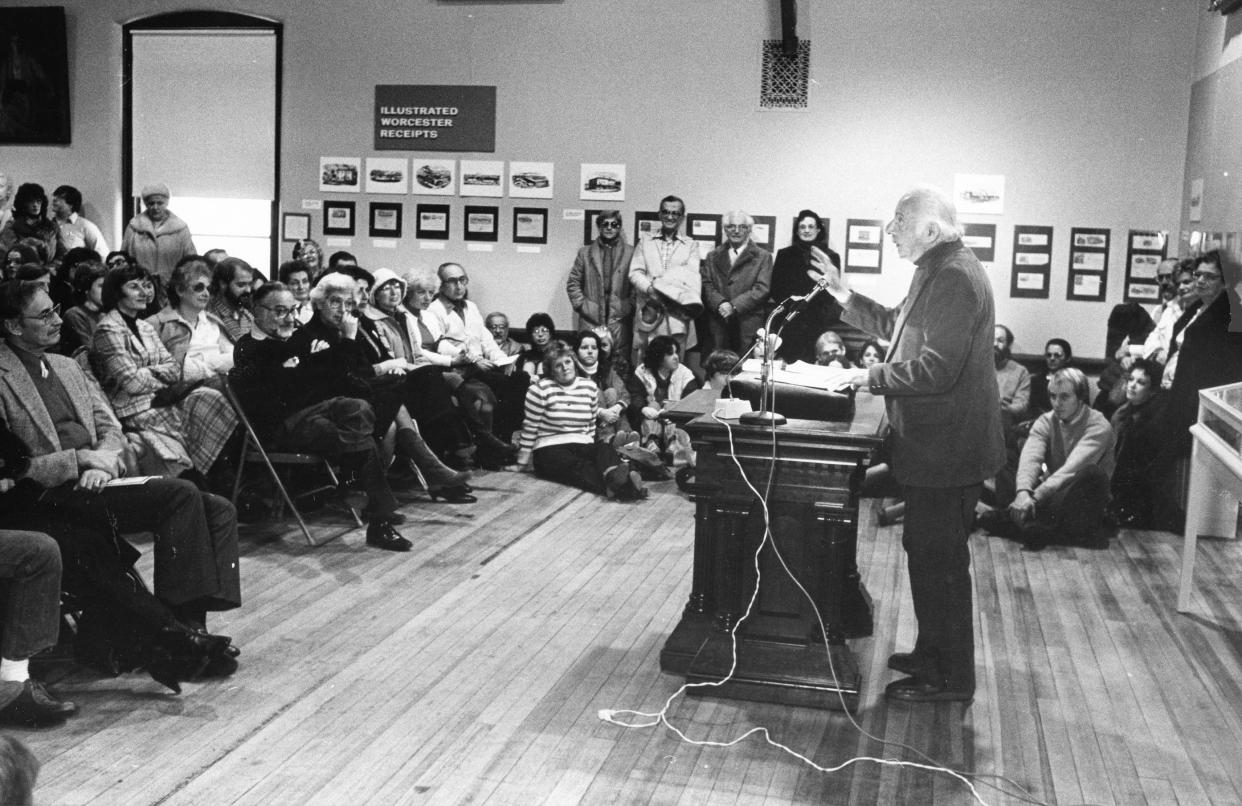

"Her presence is not comforting by any stretch," said poet, author, artist and educator Judith Ferrara of Worcester, who attended poetry readings given by Kunitz. "Unaffectionate, unforgiving, too busy to pay much attention," she said.

Kunitz (1905-2006) never knew his father. Solomon Kunitz swallowed a bottle of carbolic acid in Elm Park, committing suicide on June 2, 1905, less than two months before his third child and only son, Stanley, was born. Financial troubles had taken a heavy toll from the time the dress-manufacturing shop he had started with his wife, Yetta, at the corner of Winter and Harding streets, was gutted by fire. Besides his unborn son, he left two daughters.

Yetta Dine, who married Mark Dine, a clerk and salesman in Worcester in 1910, but was widowed again in 1920, refused to speak of Solomon in the house. In the poem "The Portrait," Kunitz writes "She locked his name/in her deepest cabinet/and would not let him out,/though I could hear him thumping ..."

In the poem’s final lines, Kunitz as a boy discovers a portrait of his father in the attic and brings it downstairs where his mother sees it in his hands: "she ripped it into shreds/without a single word/and slapped me hard./In my sixty-fourth year/I can feel my cheek/still burning."

Ferrara said during a recent interview that she was teaching a class on Kunitz at the Worcester Institute for Senior Education (WISE) program at Assumption University when some students asked about the grim portrayal of his mother.

Initially, "I have to admit that she (Yetta Dine) she was rather minor in my focus," she said.

Still, "I started wondering about his mother," Ferrara recalled. "I said there's got to be more."

'I was brought into the world much too early'

Her book, "A Feast of Losses: Yetta Dine And Her Son, The Poet Stanley Kunitz," which was published on June 13 by TidePool Press, shows there is lot more to learn and indeed appreciate about Kunitz's mother.

Without denigrating Kunitz, now recognized as one of America's great 20th century poets, Ferrara, as Grafton author Nicholas Gage puts it in his praise for the book, "has dug deep into the Kunitz family archives to humanize the woman whose celebrated son was too angry to appreciate the impact she had in forging the poet he became."

The book is also the result of "a small miracle" of discovery and finding sources that remarkably, but only just, physically survived the years.

"A Feast of Losses" includes Ferrara's transcription of a memoir that Yetta Dine had written at her son's encouragement. The memoir recalls Yetta Dine's childhood home in the small town of Yashwen in Lithuania, where Jewish families like hers lived generally in peace but also in an atmosphere of latent menace that one day would bring a dreadful reckoning with the Holocaust. The memoir begins, "Without my consent, I was brought into the world much too early in the year 1866 — and if I had my choice, it was the in wrong place, Yashwen, a God-forsaken town in the Province of Kovno, Lithuania."

Yetta describes her family and life in the town. Her father unquestionably rules over his wife and six children, but his health and finances were ruined after being accused of supporting Russia during the Polish-Lithuanian revolution. He barely escaped hanging.

The memoir also covers Yetta's coming to New York’s Lower East Side in 1890 and learning the garment trade before moving to Worcester in 1893 to marry Solomon Kunitz. In New York, Yetta comes across as establishing a feisty, independent presence, making relatively good money in the garment shops due to her own diligence and creativity.

The memoir ends, "I worked there until I left New York to be married in Worcester, Massachusetts."

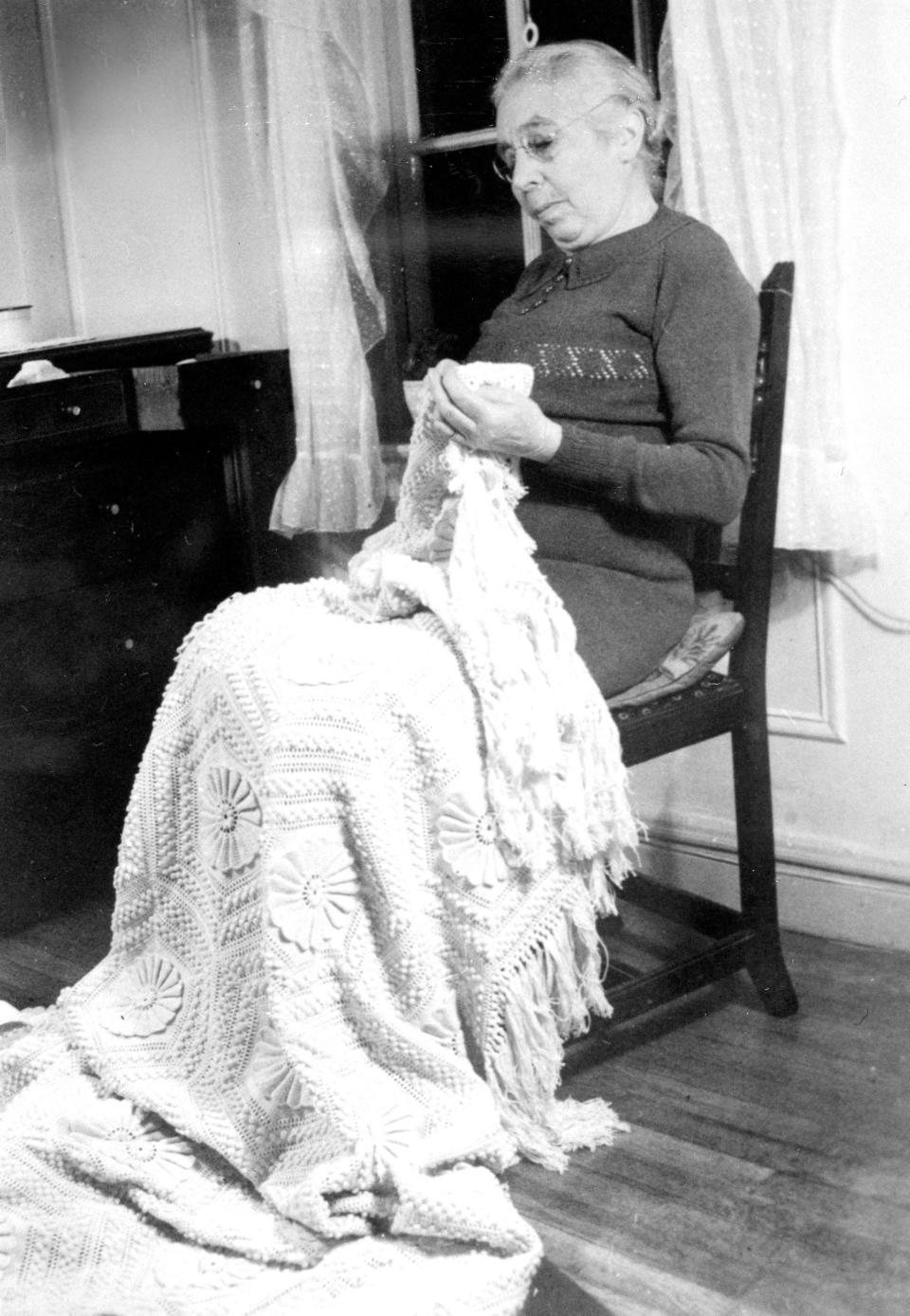

"Her writing reveals an outspoken, shrewd, compassionate, independent, resilient, and loving individual with strong family ties," Ferrara writes.

The memoir is also very well-written, something people have commented on to Ferrara since the book was published.

"I just corrected her punctuation and spelling. It's all her. The apple doesn't fall far from the tree does it? He (Kunitz) must have got some of his talent to write from her," Ferrara said.

'The sweet drops in the bitter cup of my struggling'

Besides the memoir, "A Feast of Losses" includes letters as well as a diary that Yetta Dine wrote in a rest home in 1951 after she suffered a stroke. She died in 1952.

In the diary Yetta Dine knows that she is at the end of her journey and begs for death to ease her suffering. She also writes about "the sweet drops in the bitter cup of my struggling" — small moments of happiness.

But Ferrara said she was stunned when she found in the diary Yetta Dine attempting to write a poem, with draft lines such as "Back to friends of yore/ Back through the dark and/dreary ways to life/health and hope once more."

'"Look at what she did in the diary — what does she do? She starts to write a poem," Ferrara said.

"That stunned me, that she had to express it by writing a poem. People may look at it and say, 'Oh that's doggerel. It should have more structure.' But this is a poem. It represented her trying to pull herself out of despair and that's what poetry can do for you. She was feeling so very abandoned, so very depressed. Her poetry is one of the strongest pieces of evidence of why do people have to write poetry."

In Ferrara's research she came across a draft of Kunitz's poem "The Portrait" which had the line "... and slapped me hard,/inconsolably sobbing."

Kunitz erased "inconsolably sobbing."

"He took that line out. That would have changed my experience of the poem," Ferrara said. And the mother.

Ferrara writes in "A Feast of Losses" that "Stanley Kunitz created a narrative which would not detract from his legend — a son haunted by the suicide of his father and angered by his mother's stubborn silence by the event."

However, "Yetta Dine's biography/memoir acts as a counterbalance to Stanley Kunitz's dramatic lyric poetry and interviews," Ferrara writes. "Now a larger and more intricate, but perhaps less comfortable garment has been created."

'Learning how to write, how to learn'

For a key period while growing up, Kunitz had lived at 4 Woodford St., off of Providence Street on Worcester's East Side. It was there that his stepfather Mark Dine died of a heart attack while putting up curtains in 1920.

In a fictional piece related to what happened that Kunitz submitted to a professor while he was a student at Harvard University that Ferrara cites, a young man knows that death has occurred and feels his heart harden. "He hears 'There is no God.'"

Kunitz graduated from Classical High School in 1922, and received bachelor's and master's degrees in English and philosophy from Harvard University. Any thoughts of teaching at Harvard ended when he was told by the university that the Anglo-Saxon students would not like to be taught by a Jew.

During an interview with the Telegram & Gazette at his house in Provincetown just before his 100th birthday, July 29, 2005, Kunitz pointed out that his first job was as a reporter with the Worcester Telegram. "It was a good learning experience," he said. He joined the Telegram in 1927, just after getting his master's degree, and worked at the paper for about a year. One of his Telegram assignments was covering the Sacco and Vanzetti trial in 1927.

Kunitz moved to New York City in 1928 and worked as an editor and teacher while accumulating applause and awards for his poetry. He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1959 for "Selected Poems 1928-1958," and in 1995 received the National Book Award in Poetry for "Passing Through: The Later Poems, New and Selected." In 2000, the Library of Congress named him Poet Laureate. He died May 14, 2006, a few weeks away from his 101st birthday.

For a while, a long absence from visiting Worcester was deliberate, but he later said that it was important to return to his roots and try to understand them.

"I still have fond memories of my early years (in Worcester), despite the losses that you know about. But I really look back on those years as years of learning about the world, learning how to write, how to learn," he said.

In 1985, Kunitz drove by 4 Woodford St. with his wife, Elise Asher (who died in 2004), to the house to take a look at the home he hadn't been inside in 60 years. Greg and Carol Stockmal, who had owned the house since 1979, invited him in and a great friendship developed. Along with many letters back and forth, the Stockmals would also send Kunitz a shipment of pears from a pear tree he had planted with his mother. Kunitz dedicated his famous late poem, "My Mother's Pears," to the Stockmals.

The Stockmals subsequently offered tours of Kunitz's boyhood home on occasion (the house would be restored to its original interior appearance).

'It's all so familiar, all so special'

The Worcester County Poetry Association asked Ferrara and her husband, the poet John Gaumond, to room sit when they would have the house tours.

Ferrara said she had become a fan of Kunitz's poetry. "I knew some of the places (Kunitz refers to). We'd enjoy the poetry. It's all so familiar, all so special." She holds degrees from the University of New Hampshire, Fitchburg State University and the State University College at Buffalo. In 2018, she received the Stanley Kunitz Medal from the Worcester County Poetry Association. The medal is presented annually "to a person with a strong Worcester County (Mass.) connection who best exemplifies Stanley Kunitz’s life-long commitment to poetry and poets."

Greg Stockmal usually gave the house tours but died in 2008. Carol Stockmal asked Ferrara to develop a docent program.

As a reference guide, it grew to 200 pages of information about the house, Stanley Kunitz’s poetry, and his parents’ life. The guide ended up in Princeton University’s Archives and Special Collections where Kunitz had sold his papers. Ferrara went to Princeton to do research, and when she finished the reference guide Princeton accepted it into the papers.

Meanwhile, in 2010, Kunitz's former home at 4 Woodford St. was officially designated as a Literary Landmark by the American Library Association/Association of Library Trustees, Advocates, Friends and Foundations.

Gretchen Kunitz, Stanley Kunitz's daughter and only child, visited Worcester for the first time for the occasion, and met Ferrara.

Later, Ferrara, who knew that Stanley Kunitz had suggested to his mother that he write a memoir, asked Gretchen Kunitz if she knew where such a memoir existed.

"I knew that Gretchen had to have it, if anybody did. Or else it was destroyed," Ferrara said.

In a foreword to "A Feast of Losses," Gretchen Kunitz writes, "As Judith's research uncovered more history about my father's family, we began an email correspondence. When she inquired as to the existence of my grandmother's memoir, I was delighted to inform her that the original memoir, along with her diary and letters were stored in my attic. I sent these materials to Judith."

Ferrara said, "As soon as I started reading, I knew there was something very interesting and special about this woman."

There was also a surprise of a different sort.

"When I saw it I think rather than shocked I was more afraid the pages were going to crumble in my hand. It was very cheap paper. The pages were never stored in a vacuum," Ferrara said of the manuscript and diary.

Ferrara contacted the American Antiquarian Society for help, and the papers were put in special archival folders.

"It was a little miracle. Very little text was lost. I was so super cautious," she said.

"The transcription was another thing. I could do four pages a day. It took me weeks transcribing ... The challenge was, I don't want to wreck this."

Stanley Kuntiz's poem "The Layers" includes the lines "How shall the heart be reconciled/ to its feast of losses?"

"'A Feast of Losses' is such an appropriate title," Ferrara said. Her original title was "A Few Sweet Drops in my Bitter Cup," which would also have been fitting.

"Seeing her son's name on a faculty door — these were moments, they were sweet drops in her bitter cup," Ferrara said.

"But there's no doubt about it, she had a lot of loss. Stanley didn't directly experience the loss of his father, but he did experience the loss of his step father. Yetta was raising three children alone."

Kunitz's sisters lived to adulthood and had children but died relatively young.

Did Kunitz love his mother? Some of the letters he wrote to her quoted by Ferrara do not brim with great affection.

'A contest of strong wills'

Toward the end of his long life, Kunitz said he had changed the way he feels about his mother, "but it's way to late to make a change in this life (in his poetry)," Ferrara said.

"I think he says she was a strong willed person and it was a contest of strong wills," Ferrara said.

With his step father Mark Dine "he did have a male in the house. There was always the need for a father, and when the mother is left to do the raising of the son there is a real struggle ... She was who she was, a strong person. I think he was trying to be himself. He was expecting something (mothering) that she could not give him. Dealing with her loss forever changed her, and yet her grandsons (from her daughters) became her children in as sense."

One relative implored Ferrara to "make sure you tell how loving she was."

Ferrara said "Every family is a dynamic. It's changing. I think Stanley knew that when he came into the world, things were dire."

Having done so much research and new discovery about Stanley Kunitz, is the next step for Ferrara to write a full biography of the poet?

"That's not anything I'm headed for," Ferrara said emphatically. "I'm hoping that this book will provide a basis or a help to someone who is doing that. That (a biography) would take many years more. Anyone who reached out to me I will open up to that person, but I'm not the one for that job. I hope I'm around to see it, that's all I can say. Nothing would make me happier. He deserves a biography, absolutely," she said.

In addition to outlets such as Amazon.com, "A Feast of Losses" is available at TidePool Bookshop, 372 Chandler St., Ferrara said. She gave one of her early readings from the book there in June.

The initial reaction has been very encouraging. "I've had some wonderful responses from people who have read it or attended one of the readings," Ferrara said.

The revision of the draft line from "The Portrait" ("inconsolably sobbing") sparks a conversation," Ferrara said.

"People are saying she was such a good writer ... One person said, 'I really liked her but, I could see that she could be difficult.' That kind of capped it," Ferrara said.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Sweet drops in a bitter cup — new book depicts Stanley Kunitz's mother