Johnny Cash’s ‘boom-chick’ acoustic style is worthy of more attention

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

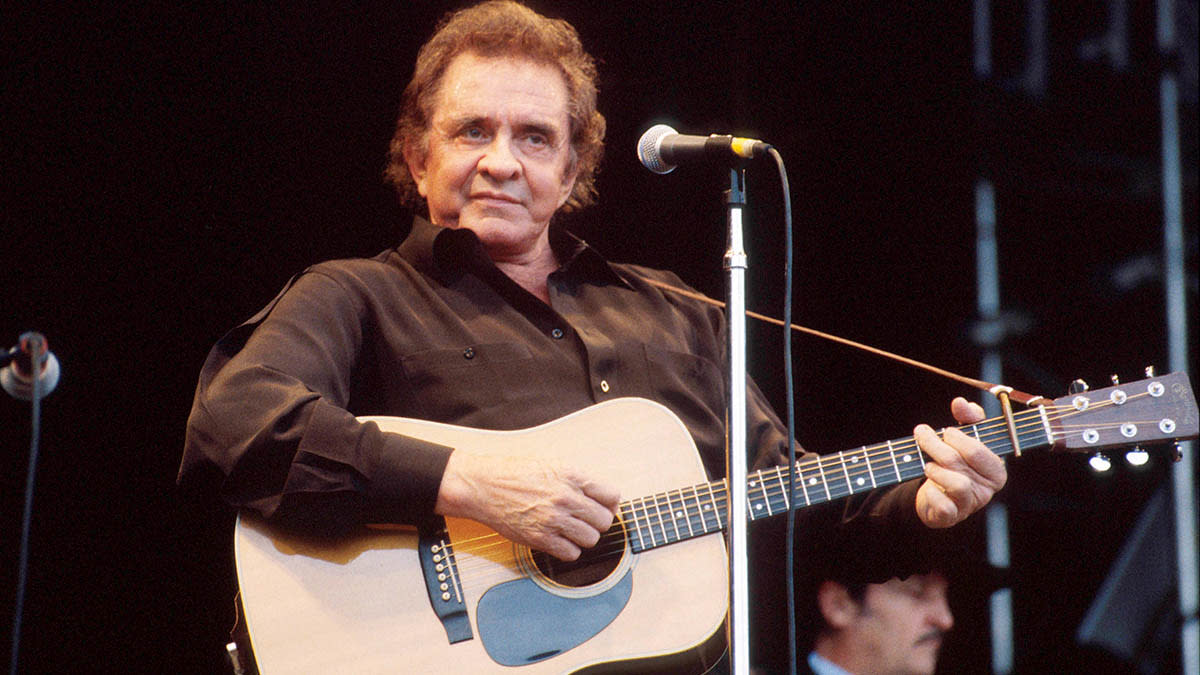

Think of country music and it’s hard not to conjure up an image of the legendary ‘Man In Black’, original outlaw country legend Johnny Cash. His warm bass-baritone voice and relaxed yet tight strumming patterns are immediately recognisable and laid the foundations for country rhythm guitar in the decades that followed.

His mournful songs of heartache, struggle and trouble put him alongside Hank Williams on the pedestal of country fame. Growing up in Arkansas in the 1930s Cash started his working life in cotton fields at the age of five and would have learned the tradition of the ‘work song’ from an early age singing along with his family and fellow workers. Guitar lessons came courtesy of his mother and a friend and by age 12 he was already writing songs.

After a spell in the army Cash set out on his musical career in the early 1950s with the ‘Tennessee Two’, guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant. Perkins’ country/rockabilly lead style married perfectly with Cash’s more traditional stripped back, strumming-based accompaniment and although they started off performing gospel music soon they took on rockabilly as their main sound.

Listen to Cash staples like Folsom Prison Blues, I Walk The Line, and Ring Of Fire (actually written by June Carter and Merle Kigore) and you’ll hear Cash’s simple yet effective rhythm guitar parts at play. Driving, tight and often percussive he locked in with the snare to create a big sound that heralded the arrival of a harder approach to country music. Perkins’ lead guitar and fills were given the perfect foundation in Cash’s driving acoustic playing.

Cash’s rhythm playing initially seems simple, as there are open chords and a basic strumming pattern. There are challenges though, and while the alternating basslines that punctuate each chord seem straightforward, hitting the correct bass string each time is harder than it seems.

His style demands a relaxed strumming hand and an even dynamic on each strum –lose control here and your playing will be all over the place dynamically, and rhythmically.

You also need stamina to keep this part going so try playing this chord sequence for five minutes and see if any fatigue sets in on the strumming hand. This piece follows the classic Cash strumming sequence of ‘1 and 2 and a 3 and 4 and a’. Try the following pattern for this type of strumming - ‘down down down down up’.

You almost want to view yourself as a percussive instrument when playing in this style, as if you are an extension of the drum kit. This style is ruthlessly efficient as a practice tool – put the metronome on or record yourself and you may find some crucial timing issues are exposed. Simple isn’t always as simple as it seems.

Get the tone

Amp Settings: Gain 3, Bass 7, Middle 6, Treble 7, Reverb 2

There’s no getting away from it, an American classic is first choice for this strumming style, and a big one at that! Of course, any acoustic guitar will suffice. Cash was most often seen with Martin dreadnoughts – D-28 and D-35 mainly, though he also played Gibson guitars and could be seen with a J-200 in the late 1950s. I recorded this on a Martin Custom Shop Expert 1937 D-28.

Study piece: Johnny Cash

Bars 1-16: Cash added interest to chords with his ‘boom-chick’ alternating bassnotes in between strums. A relaxed strumming hand gives each down and upstroke equal force so the part doesn’t sound uneven.

From bar 7 the bassline moves from a sixth to fourth-string pattern on the E Major chord to a fifth to sixth-string pattern. There are two main basslines played on chords like this: root/5th and root/3rd or a combination of these. Here we are using root/5th.

Bars 17-34: Cash’s acoustic rhythm ‘trick’ was to mute the strings to emulate the sound of a snare drum or a train on the tracks. To do this either hold the chord shape in place and release the pressure on the fingers before striking the strings, or rest a finger across the strings to mute them – the third finger works well here.