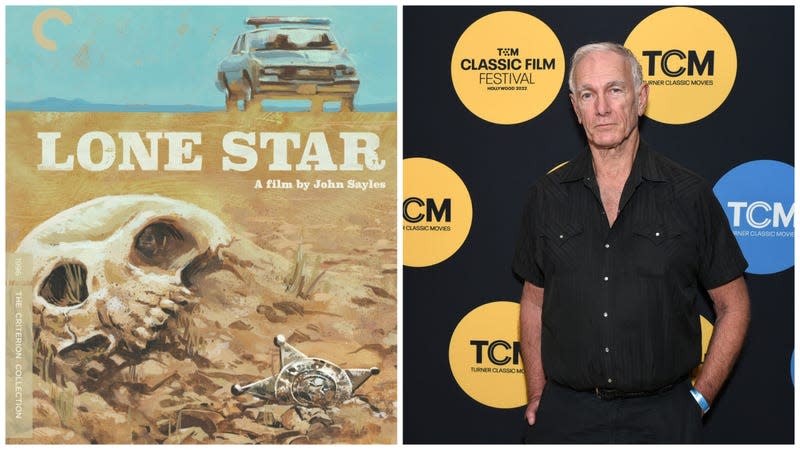

John Sayles on Lone Star, the state of TV, and making movies on the border

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

John Sayles has been a fixture of American independent cinema for nearly 50 years. Like many indie filmmakers, Sayles began his career making monster movies before directing his microbudget debut, Return Of The Secaucus 7. His shaggy, soulful, and funny look at the Baby Boomer generation was far more political and less sentimental than The Big Chill, which would benefit from Sayles’ originality only a few years later, but Sayles’ ear for dialogue, visual inventiveness, and nuanced and principled political expression is often imitated but never equaled.

Sayles has become the conscience of American cinema across his 18 films, six novels, three Bruce Springsteen music videos, and screenwriter. Nowhere is that more apparent than in his 1996 neo-Western masterpiece Lone Star. Set in Rio County, Texas, just along the border, Lone Star is a sprawling story that, in Sayles’ words, creates a “knot” that the border town’s residents can’t escape. Chris Cooper plays Sam Deeds, a disillusioned sheriff who took up the post from his father, Buddy (Matthew McConaughey), a mythic lawman whose legacy falters when the skull of Buddy’s predecessor (Kris Kristofferson) shows up just outside of town. It’s a discovery that has implications for just about everybody in town because history doesn’t repeat itself in Lone Star; it lives alongside the characters and haunts their spaces and relationships.

Through his inventive visual language and refusal to let any character go undeveloped, Sayles’ film continues to grow in relevance with each passing year. Recently released as a 4K Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection, Lone Star can find a new audience willing to face the past without fear. The A.V. Club spoke with Sayles about the film, the border, and his thoughts about the state of show business.

The A.V. Club: Lone Star continues to grow in relevance, particularly that school board scene, which hits like a ton of bricks

John Sayles: Yeah, we’ve made a lot of progress in the last 25, 30 years, haven’t we?

AVC: Are we doomed to repeat these conversations forever?

JS: Culture and history will always be a battlefield, but some things have changed. I spent a lot of time in the South, and I don’t see the Confederate flag the way that I used to see it. There are states where they’re basically saying, if you teach history the way it happens, you’ll be fired. But there have been some [states] where that kind of Confederate iconography has been reconsidered, so there is some progress. I think of it as progress. Sometimes, it’s just time. Sometimes, it’s a concerted effort on certain people’s behalf. But sometimes, it’s just, “Oh, well, grandpa’s dead. We can take the flag down.”

AVC: What would change if you were making the movie today?

JS: I was just down in Arivaca, Arizona, right at the border. First of all, there would be a big wall. The symbolic weight and literal weight of that wall would have to be dealt with. It’s just part of this big political conversation now that means votes.

But the main thing that upsettingly would have to be different: When we made the movie, there was narco activity in El Paso and Laredo. All those little border towns in between were free from that. It hadn’t moved down there. I played a U.S. Federal Border Guard in a movie, so I got to talk to the guys that were doing that job then, and they didn’t have to wear body armor.

You couldn’t ignore the drug thing. When you’re apprehending somebody who’s crossing the border illegally, you don’t know if they’re carrying an automatic weapon or not. So it changes that job quite a bit.

AVC: There are no small stories in Lone Star. These supposedly tertiary characters seem unimportant at the onset, like Enrique (Richard Coca), the busboy. When you see him bussing tables at the beginning, you don’t expect to follow his whole experience. Why is it important to add those extra layers for those characters?

JS: I was an actor before I was a fiction writer getting stuff published, and one of the things that you look for as an actor is what glues me into this story. I have this dialog, and it may be pretty small, but who is my guy, and how much does he care about what’s going on? Does he even notice what’s going on with the main characters, or does he have his own agenda?

It’s the kind of thing where I realize there’s going to be a deputy sheriff [character]. Well, this is today, not 1957, so he would probably be a Mexican-American deputy sheriff. Because of the way the population is moving and because Hispanic people can vote now, and their votes will be counted, it’s probably the end of the days of having an Anglo sheriff in this county. So I just said, “Okay, I’m going to have a scene where the deputy [played by Tony Guana] says to Sam, ‘I thought you should know the boys have approached me about running for sheriff the next time.’ And Sam says, ‘Good. You’d be a good one.’” Sam walks away from it because he doesn’t necessarily want to stay in that job, but it glues that character in. So when [the deputy] is doing his stuff, and he’s arresting somebody, and he’s giving him some shit, he’s practicing being the man. But also, he’s got this worried look on his face because he likes Sam, and he’s worried. “When am I going to tell him that I may run against him? I hope he’s walking away from the job, but I might have to run against him because I want to be sheriff, and I should be sheriff.” Well, that gives the actor a lot more to live with.

AVC: That scene is beautiful because it says so much about him and Sam. Lone Star reminds me of It’s A Wonderful Life, where, by the end of the movie, you have a sense of this whole community; you can see anyone and have a sense of who they are and how they relate to this.

JS: One of the things that I talk to people about is that [most of these characters] are going to stay in this community. Not a whole lot is going to change. The people who are going to have to leave are Sam and Pilar [played by Elizabeth Peña]. They really want to stay together, and they can’t do it at that time. The weight of the history—the personal history and the border history—is just too heavy on them. It’s going to suffocate them. There’s no way they could stay together in that town. Somewhere else? They might make it. It’s not going to be easy. She’s not going to tell her kids, “Oh, this is your stepfather and your uncle, your half-uncle, or whatever. There’s a lot of messy stuff to work out, but for the rest of the people, I just said, ”Who are you in this thing now, and are you comfortable with it or not?

So Jesse Borrego plays Danny, the reporter, and he’s got a chip on his shoulder, and he’s going to run an article about Buddy Deeds’ real estate transactions or something like that. And they’ll get a certain amount of traction, and it won’t change a whole lot.

AVC: I love the last scene, where Sam and Pilar are looking at the empty movie screen, especially after these characters evoke all these Western tropes. They’re looking at a history that’s not been written.

JS: That’s the last place that they got to be together; when they were kids, they were literally dragged apart there. So it has some real emotional weight in the past, but they’re also looking at a blank screen, and there is this possible future. They’re going to work out whether they’re going to go into that screen and live it together or not.

As you start to have a little bit more money to make a movie than your first couple, you can do a little bit more with the mise en scene, what’s in the background. Where are you? Is there construction noise, or is it quiet? Are you in a confessional? Are you in a church? Are you in a soulless office building? Are you in a Chinese restaurant that’s really busy and affects the vibe of the scene? For that heavy scene between them, which is really a two-hander scene, I don’t want to shoot it with matching close-ups. I want to see them both the whole time. I want to see both of their faces as they work this thing at the same time. But where should it be? It’s kind of symbolically from there, but also a place where nobody’s going to see them sitting together because they still have to be a little circumspect about who’s seeing us. Are we dating? We don’t want the town talking about us. So it’s way out in the boonies. Nobody goes there anymore, just like their first meeting, when they have their first big walk and talk; it’s along the Rio Grande River, where they used to go to be alone and not be seen.

AVC: Kris Kristofferson is a classical Western hero, an icon from a previous generation, and Matthew McConaughey represents a new kind of hero. Were you looking for someone to fill that cowboy role like that and evoke these archetypes?

JS: One of the first things that I said was who are the actors from Texas. Certainly, Dennis and Randy Quaid are real Texans, and they can bring that to their performance of it if it’s what’s necessary. There’s a bunch of really good actors from Texas.

Kris Kristofferson is not only from Texas; he’s from the border. He knows that world. He knows that music. He knows those redneck sheriffs, and he knows that strange other side of the tracks thing where the Mexicans, you know, you can hear their music, but they’re not in your neighborhood unless they’re your gardener. That kind of weird thing. He came from a military family. He lived down in the Brownsville area. Matamoros, that area. I’ve never seen him play a really bad guy, but he’s got that voice and that presence. He’d make a really scary bad guy. And then with with Matthew McConaughey. I knew Richard Linklater a little bit, and I really liked Dazed And Confused. One of the things I liked the most about it was that laid-back Texan, that “just keep living” guy. From [Linklater], I learned he was a film student. I asked him to do a little part, and he was so charismatic I kept making the part bigger. He’s from Uvalde, Texas. He knows how to wear the boots. He’s grown up in that world, too. When he came in to read, there was just a comfort level. A key to the guy is that I felt he could have a confrontation with Kris Kristofferson, and it could be a stalemate. And he didn’t have to stand up. It’s not like he’s going to hide. He’s going to keep sitting there and doing it, and I think he can pull it off, even though he’s only been in one movie.

That was just one of those nice things of timing. He was going to get known and be somebody we’d see on the screen again and again. But he was starting, and we were lucky. There he was when we were auditioning for guys from Texas.

AVC: Lone Star is the type of movie that would get elongated into a 10-episode miniseries today. Why is it important to tell these stories in a contained movie?

JS: Things get elongated because of economics. The hardest thing economically for people to make now is a stand alone feature. So, for the last 10 or 15 years, I’ve been trying to pitch these ideas. And they always say, “Can you make a series?” because that’s what’s getting made.

Quite honestly, yeah, you could make this into a series. I wanted to make it into a feature because you have to see the knot. You have to see the intertwining right away. And you can’t be treading water and say, “Oh, we’re going to spend half this episode in this community, but nothing’s going to really happen.” Our movie City Of Hope is like that. Of course, you could make it into a miniseries. You could make something like The Wire, which was terrific. But as a standalone feature, you say, “Oh my God, look at this tangle that this movie tells us.” There’s an arc to it, and there’s an immediacy to it that doesn’t happen over months and months and months. It happens over days. They are different animals. Unfortunately, there are really good features that get pushed into being a series, and then they run out of story about five episodes in. Then either they do something brilliant, like, “Let’s just change the game and make up a new whole thing that we’re aiming at,” or they start to tread water. Some of them do that better than others, and they last longer.

The guy who I thought did the best job of it was David Lynch. When he did Twin Peaks, it took two years to figure out who killed Laura Palmer, But he kept the thing going because it was just so weird. What’s going to happen next? Anything could happen here, and it’s going to be interesting when we get into it. It’s much more twisted than just some girl got killed. That was that was a real feat: One murder, two years, and it just got more and more crazy and interesting. That’s not an easy thing to do.

AVC: Lone Star has a bit of Twin Peaks in it, where sometimes characters appear from a different time, and sometimes it feels more modern.

JS: Time has passed, and I didn’t put a cut between the transitions from 1957 to what the modern time was when we made it. But things had changed. The style had changed. Those Charlie Wade sheriffs in the American South or the Southwest don’t get to do that anymore. Occasionally, they do, and they don’t last very long. I wanted to show this is what people had to put up with back then. This guy could run the town and kill pretty much whoever he wanted to. Nowadays, you might be just as corrupt as him, but you don’t get to do it above the table the way that he got to. Everybody just said, “Well, that’s what we hired him for, you know, to keep the Mexicans down.” You know that. That’s what he’s good at. That’s not what that’s not the job anymore.

There is this phenomenon—you really notice it in Los Angeles—years ago, it was quite a problem, which is cops watch cop shows. In Los Angeles, it was Dragnet, and he worked with the LAPD. There was a certain swagger to these guys that they partly got from the movies. Sometimes that’s okay. Sometimes it’s a bit of a problem, you know? This guy has the music going in his head. When in reality, he’s giving me a fucking parking ticket. Why is this thing getting ratcheted up here? I wanted that kind of feeling that there was a guerilla war between the Texas Rangers and the Hispanic community in South Texas for decades after the U.S.-Mexican War. It was bad. People were getting murdered, but people with badges were doing some of the murdering. I wanted Charlie Wade to be a holdover from that. It’s 1957. This is when people are getting lynched. Mexican Americans, as well as African Americans in America, fairly often. He’s not so much somebody who’s just a creation of the movies. He was a real guy. There were guys on the border who were famous. So you don’t fuck with this guy. You don’t go into his town.

We know a guy whose father got to be the mayor of a little Texas town, and he was more of a moderate, so he changed [the slogan on the sign] when you drove into town. It used to say the “Whitest town in Texas.” He changed it to the “Nicest town in Texas.” But it used to be, “You do not let the sun set on you if you’re not white in this town.” Mexican, Black, Native American, you get out. That was 1957.

AVC: Sundance is coming up. Given that the strikes have prevented Hollywood from producing anything for roughly six months, what impact could that have on indie movies? Could it spur a buying spree?

JS: Yeah, it could. Probably not the big studios, but the smaller distribution people might buy a little more. You know, “If we’re going to stay in business, we’ve got to have something come out. We’ve got all these employees. They have to make trailers and do some distribution, work on something. So let’s take a good hard look.” Occasionally, that means you’ll get a little bit more money than you probably should if there’s a bidding war or something like that. But everybody’s just guessing on what’s going to be commercial. Our friend Larry Estes, one of his first jobs working for a video company, was to find things for them to put out and find a theatrical distributor for them. One of the first movies he saw was Sex, Lies, And Videotape. And it was like, “Okay, my career is made.” But that doesn’t happen that often. More often, it’s like, “Well, I like this movie, but is there a way for us to get an audience for it?” You’re always taking a risk, and unfortunately, most people who take over the official big movie business want to get rid of the risk. They want to rely on their algorithms. I’m afraid you’re still taking a risk even if the algorithms say this will probably work.

AVC: Will we see a new John Sayles movie anytime soon? I’ve read that you have a Western in the works, and a film about the 1968 Democratic convention in writing. Is there any movement on these?

JS: Those have been written for several years, and I’ve been trying to raise money for them for several years and have failed for several years. They may or may not happen, but they’re written. I like them; they’d be good movies. But the gods of financing. It’s really hard to get a standalone drama made these days. So we just keep our fingers crossed, and every once in a while, we have a meeting.

AVC: Is there a chance you and Joe Dante will make a monster movie again?

JS: I wrote a screenplay called Them! Again that’s like a modern take on the giant ant movie. I sent it to Joe and said you should direct this. Basically, Warners owns the property, and we haven’t been able to wrench it away from Warners. Who knows? Now, it’s one of those things that would have been a really good movie if Joe could have gotten to direct it. But because it is based on a movie that belongs to somebody, it’s hard to crack that nut, especially if they’re busy being bought by international multinational corporations and putting movies on the shelf and this and that. There’s a lot going on at Warners now.