Jimmy Buffett, ‘Margaritaville’ Singer Who Turned Island Escapism Into an Empire, Dead at 76

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Jimmy Buffett, the singer-songwriter known for his enduring anthem “Margaritaville” and a businessman who transformed the 1977 song into an empire that encompassed restaurants, resorts, and more, has died at the age of 76.

A statement released on his website and social media late Friday read, “Jimmy passed away peacefully on the night of September 1st surrounded by his family, friends, music and dogs. He lived his life like a song till the very last breath and will be missed beyond measure by so many.”

More from Rolling Stone

An obituary on Buffett’s website later revealed that the singer died following a four-year battle with Merkel cell skin cancer. Buffett had postponed tour dates due to unspecified “health issues and brief hospitalization” last year and postponed more shows this year after an unexpected trip to the hospital “to address some issues that needed immediate attention.” “He continued to perform during treatment, playing his last show, a surprise appearance in Rhode Island, in early July,” his website noted.

“A poet of paradise, Jimmy Buffett was an American music icon who inspired generations to step back and find the joy in life and in one another,” President Joe Biden tweeted Saturday. “We had the honor to meet and get to know Jimmy over the years, and he was in life as he was performing on stage – full of goodwill and joy, using his gift to bring people together.” The president also sent his condolences to Buffett’s family and “to the millions of fans who will continue to love him even as his ship now sails for new shores. “

“Jimmy painted pictures and short stories in all the songs he wrote. He taught a lot of people about the poetry in just living, especially this kid from East Tennessee…,” Kenny Chesney said in a statement to Rolling Stone.

Buffett spent most of his life living in or near the tropics, and his country-rock music allowed listeners to experience the carefree feeling of a beach vacation whether or not they had saved up any paid time off. His name alone evokes visions of white sands and fruity drinks, and his devotees, “Parrotheads,” have organized themselves into a genuine subculture, with over 200 local chapters across the United States. A shrewd businessman, he developed multiple chain restaurants inspired by lyrics from his songs. In 2023, Forbes magazine estimated his net worth to exceed $1 billion.

Such success would have come as a surprise after his first album, 1970’s Down to Earth, sold less than 400 copies.

Buffett was born on December 25, 1946, in Pascagoula, Mississippi. He grew up in Mobile, Alabama, where his father worked at the Alabama Dry Docks and Shipyard. His grandfather was a sea captain who filled Buffett’s imagination with stories of his ocean journeys around the world.

Buffett left Mobile as soon as he could, but the city’s outsized celebration of Mardi Gras, the oldest Carnival holiday in the United States, shaped his outlook and his art for the rest of his life. “The way I understand it growing up, Mardi Gras was a time for partying, and partying at Mardi Gras took on a whole other definition,” he wrote in his memoir, A Pirate Looks at Fifty. “To most people, it was allowing themselves to disregard many of the rules by which they lived most of their lives.”

In college at the University of Southern Mississippi, Buffett learned guitar with the hope of impressing girls. The mission didn’t succeed, as he had been the first to admit, but his ambitions quickly grew. By his senior year, he was picking up gigs in New Orleans, and after graduation, he and his wife Maggie Washichek moved to Nashville to pursue his music career. (He has claimed that 26 labels rejected him in Nashville.)

He made his first trip to the Florida Keys in 1971, as a passenger in Jerry Jeff Walker’s 1947 Packard. Buffett left Nashville after he and Washichek split, and while playing gigs in Miami he tracked down Jerry Jeff, whom he had met while working as a reporter for Billboard. They fixed up the car together and drove it down to Key West. Soon, he told Jerry Jeff to go back without him. Buffett had found his new home

In Key West, Buffett fell in with a crew that included novelists Tom McGuane, Jim Harrison, and Tom Corcoran. “You could get by cheaply in this run-down, undone, semi-Bohemian place and it attracted various rebellious types,” McGuane remembered.

“It was still a Navy town,” Buffett said of Key West. “It was a gay town. It was a hippie town. It was a local fisherman’s town. You want a melting pot? It was just that. It never ceased to give me ideas or hear stories from which those first songs came.”

The scene was centered around a bar called the Chart Room, where Corcoran and later Buffett worked. Buffett picked up a gig playing cocktail hour at a bar called Howie’s Lounge. “I got a job as a mate on a fishing boat so I played by day, go raise hell all night, sleep for a few hours, and then get up at 4 o’clock in the morning and go catch fish. So I thought, ‘I have got this made.’”

Over the course of 1973 and 1974, Buffett would release three albums that charted a new course for the singer. A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean has plenty of Nashville twang — it was recorded at Tompall Glaser’s studio there — but tracks like “Why Don’t We We Get Drunk” and “Grapefruit – Juicy Fruit” brought the Key West joie de vivre into his music for the first time. These songs are timeless, in the sense that they capture the spirit of a place where people are too unbothered to worry about what time it is.

Up next was Living and Dying in 3/4 Time, the most cynical record of his career — in fact, the only one. Yet his cynicism was aimed wholly at Nashville, shot like a long-range missile from his new base. The near complete lack of lyrics about jellyfish, blackened shrimp, and other finer points of Buffettiana make this record a good starting point for Buffett skeptics. The sharp songwriting makes it a fan favorite, too. Yes, there is a line about lobster in “The Wino and I Know,” but other than that, the pleasures of island living stay in the background.

That made A1A, his next album — named for the one road in and out of Key West — something of a change of address announcement. The first side was in line with Buffett’s previous releases, but Side Two, opening with “A Pirate Looks at Forty,” offered a suite of songs entirely about or inspired by his island home. Three of the five songs take place at least partly on the water, and the two that don’t are both set shoreside, finding the singer either drinking by the beach or waking up hammock after doing so. He had found his artistic purpose, and he never second guessed it.

He just needed an audience. “Come Monday,” off Living and Dying, had given Buffett his first hit, rising to Number Three on Billboard’s Easy Listening chart and Number 30 on the Hot 100. A1A became his first successful album, reaching Number 25 on the charts and earning him and his Coral Reefer Band a slot opening for the Eagles.

Yet the true breakout was Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes, which was released in 1977 and contained “Margaritaville,” Buffett’s signature song. Buffett had started writing “Margaritaville” in Austin when he bridged the gap between a morning hangover and an afternoon flight with a drink. “I had a margarita, which helped with the hangover, and in the car on the way to the airport the chorus of a new song started to come to me,” he said. “I wrote a little more on the plane and finished the rest of ‘Margaritaville’ back in Key West.”

Buffett intended the song to be, in part, a send-up of tourists who flocked to Key West, a subject he had previously touched on “Migration” off A1A. There was even an extra verse, left off the record, about “Old men in tank tops/Cruisin’ the gift shops.” But Buffett, to his credit, may have identified with the song’s vision of tropical purgatory too closely to fully sell the critique. Just as “Born in the U.S.A.” has often been mistaken for a patriotic anthem, “Margaritaville” called tourists to Key West in numbers Buffett could never have anticipated.

Buffett didn’t exactly dissuade people from this interpretation. Buffett lent the Margaritaville name to two Key West tourist destinations: the Margaritaville Beach House resort and the Margaritaville Restaurant, the latter the flagship for dozens of restaurants. The empire would go on to include Margaritaville resorts, multiple casinos, Margaritaville at Sea cruises, and Latitude Margaritaville retirement communities.

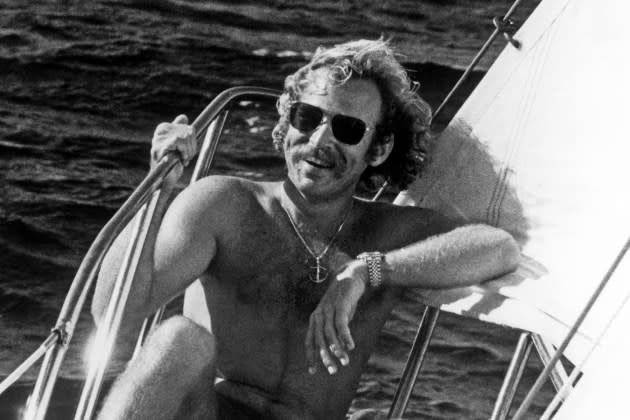

Buffett’s own Key West era ended in 1977, when he sublet his apartment to Hunter S. Thompson. When Rolling Stone put him on the cover in 1979, he was living on the island of Saint Barts, where he was able to access an even higher plane of island existence, making all kinds of new friends in the process. Saint Barts drug smugglers, journalist Chet Flippo wrote, “swear by the man and would no more make a run in their boats without Buffett cassettes on board than set sail without a few cases of [Heinekens].” Buffett’s own boat was named the Euphoria II. In the cabin hung a framed picture of Buffett in the Oval Office with Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale.

Few artists of Buffett’s stature, or net worth, have relied so little on album sales. Songs You Know By Heart, a greatest hits album released in 1985, was the best seller of his career, going seven-times platinum. None of his 1980s albums climbed higher than Number 30 on the Billboard 200, yet it was during this time that he developed one of the most reliable touring operations in popular music.

It was also during this time that the fans who turn out to Buffett shows year after year became known as Parrotheads. The term was coined by Timothy B. Schmit, then the bassist for the Coral Reefer Band. “People had already started wearing Hawaiian shirts to our shows, but we looked out at this Cincinnati crowd and they were glaringly brilliant to the point where it got our attention immediately,” Buffett said. “I said ‘Look at that!’ Then Schmit says to me, ‘They look like Deadheads in tropical suits. They’re like Parrotheads!’”

Buffett remained a reliable draw, and a reliable good time, until the end of his life. Even in 2010, the trade publication Pollstar named Buffett the tenth biggest touring artist of the decade, tallying 4.5 million ticket sales over the previous 10 years. For Buffett and his fans, each show was a minor Mardi Gras, a space where people could forget about everything else going on in their lives and enjoy something fun, festive, and a little weird.

In the mid-1980s, Buffett recorded two albums in Nashville, Riddles in the Sand and Last Mango in Paris. Although they marked a détente in his relationship with Music City, their modest airplay hardly foreshadowed the influence Buffett would have on country music in the following decades. In the early 2000s, thanks to fellow island-hopper Kenny Chesney, country radio was far more Jimmy than Willie or Lefty. Two songs that featured Buffett, Alan Jackson’s “It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere” and the Zac Brown Band’s “Knee Deep,” even went to Number One, the only two Number One hits of his career.

Both songs capture the feeling of escape that was so essential to both Buffett’s music and his life. The singer spent his final years touring, sailing, and occasionally even acting. He always kept a sense of humor about his exploits. In The Beach Bum, he portrayed an exaggerated version of himself, helping Matthew McConaughey’s Moondog (an exaggerated version of Richard Brautigan) navigate an exaggerated version of Key West. In Jurassic World, he played a bartender at a Margaritaville location set in the movie’s dinosaur theme park.

“You know Death will get you in the end,” Buffett wrote in A Pirate Looks at Fifty, “but if you are smart and have a sense of humor, you can thumb your nose at it for a while.”

Best of Rolling Stone