Jim Morrison’s Sister Reveals His Last Wishes, From Wanting a Family to Quitting Music

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Jim Morrison’s younger sister was escorted into a bank vault to see the trove of notebooks that the 27-year-old music god had left behind after his tragic death, she was overwhelmed.

In 2009, upon gaining control of half the estate after her parents passed, Anne Morrison Chewning found herself partially responsible for carrying on the legacy of the The Doors frontman. The 74-year-old and her brother Andrew own half the estate, while the other half is under the supervision of the family of Morrison’s late partner Pamela Courson, who died of an overdose in 1974, three years after Morrison, also at the age of 27.

“I didn’t realize how much we had,” Chewning tells The Daily Beast. “It was very exciting because I’ve been wanting to see them forever. Then, of course, we had to decide what we were going to do with them. What do you do with someone’s journals like that?”

Michael Caine Is One of the Coolest Motherf*ckers Alive

While perusing the 28 journals and various other fragile loose papers that Morrison had filled with his musings, poetry, screenplay ideas, and lyrics, Chewning came across one page titled “Plan for Book.” It spelled out exactly what Morrison had in mind for all his writings—so that’s exactly what she did.

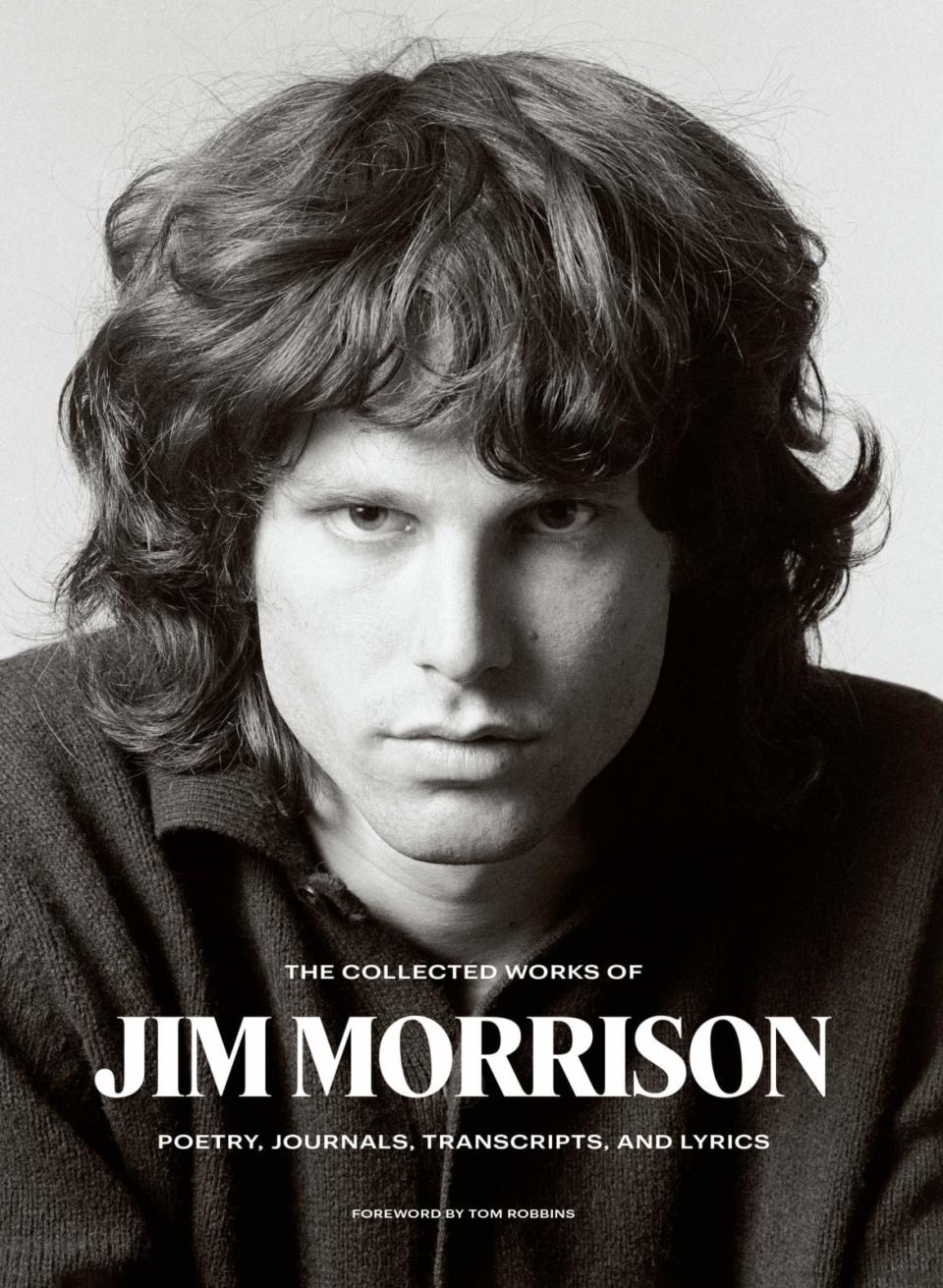

The result is The Collected Works of Jim Morrison, out June 8 and published by HarperCollins. It’s a heavy-duty, nearly 600-page book that contains the entire contents of Morrison’s journals, complete with full-sized photos of the notepads themselves.

The volume of work is astounding. There’s the early poems Morrison wrote in elementary and high school, his first mentions of the Lizard King and Dionysus; recurring themes of Americana, eroticism, and violence; his screenplay for The Hitchhiker; family photos; and a haunting epilogue compiled from Morrison’s thoughts scattered throughout his writings—the closest he’ll get to saying goodbye.

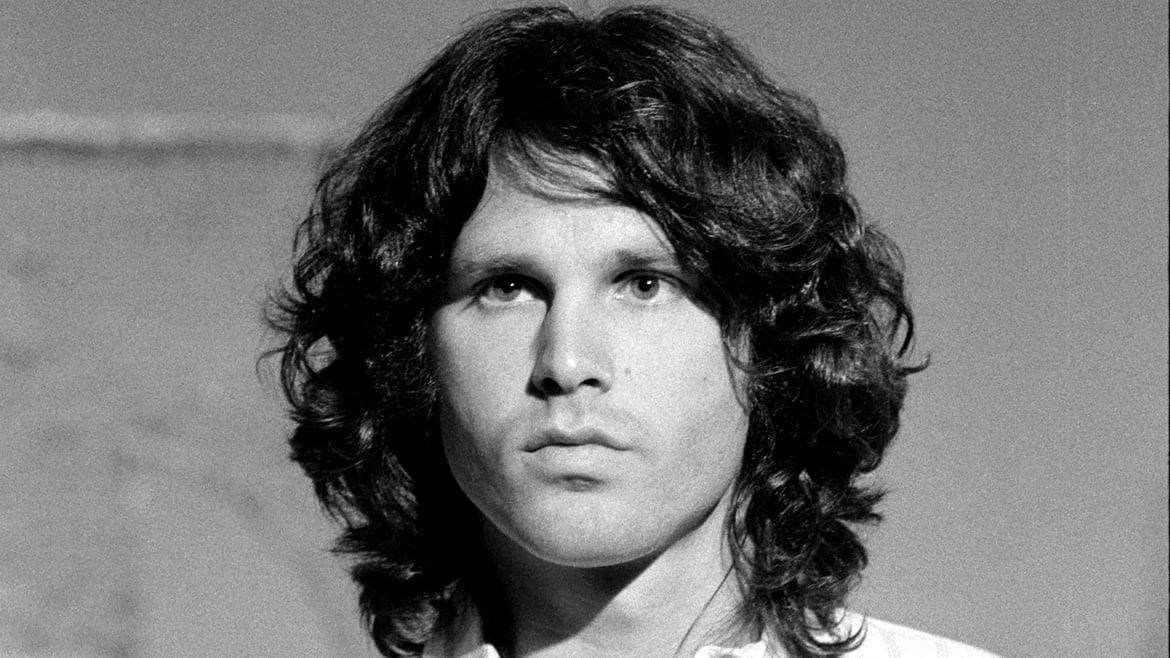

It was important to Chewning and the family that Morrison’s vision was followed and that he was the lone voice throughout the book, including in the sections that offered commentary and explanation to his sometimes difficult-to-decipher writings. Even choosing the stoic black-and-white photo of Morrison for the book’s cover was intentional—designed to peel back his larger-than-life persona and reveal his true depth.

“There’s so many young people who just see him as a rock star,” Chewning explains. “I want to dispel the ‘Lizard King’ and all those things that you hear. We wanted the reader to see the complete Jim, to see that he was a full writer in multiple areas, thinking in lots of different directions. I didn’t want an interpretation. I wanted this to be Jim and in Jim’s words, talking about himself and explaining his words, not other people’s input.”

Working with author and close Morrison pal Frank Lisciandro, who penned the book’s introduction, the musician’s poems are arranged in chronological order, although we can’t be sure since Morrison often didn’t date his entries and bounced between notebooks.

Still, Chewning says readers can see “the inner workings of his mind.” “You see his notes and his ramblings, but you also see the finished product,” she explains. “The repetition of some things and how things came to be, you know, his Hitchhiker and lyrics. I love seeing that. It’s intimate. It makes it closer to you.”

The book also shares, for the first time, Morrison’s uncensored feelings about his high-profile 1970 Miami trial for indecent exposure. He was charged with lewd and lascivious behavior and public drunkenness, which is a felony. However, he was only convicted on misdemeanor charges of indecent exposure and open profanity after getting a crowd worked up into a tizzy and allegedly flashing his penis during a 1969 concert (he was posthumously pardoned in 2010).

He was sentenced to six months in jail in October of 1970, but was released on bail while he appealed the ruling, which was still making its way through court when he died.

It’s in these legal pads and composition notebooks from the 40-day trial that fans get a clearer sense of Morrison and how he thought. Starkly different to his surrealist poetry and abstract lyrics, Morrison comes across more observational, even journalistic.

He pays keen attention throughout the trial, noting how one housewife during the jury selection had two grandchildren and “digs it.” Elsewhere, he wonders if one man’s zodiac sign is a Leo. He also seems surprised by the severity of the charges he’s facing. “The trial is really a trial,” he wrote. “It’s an education in human nature. Funky old human nature.”

In true Morrison fashion, sprinkled throughout his copious notes are also short poems and lyrics. “There once was a group called The Doors / Who sang their dissent to the mores / To be young they protested / As the witnesses attested / While their leader was dropping his drawers,” he doodled.

Morrison viewed the trial as a pivotal moment in his life, making clear that he wanted the entire transcript of his trial included in his future book. It perhaps served as a wake-up call that he was no longer fulfilled creatively by touring with his band. About halfway through the trial he scrawls, “The joy of performing has ended. Joy of films is pleasure of writing.”

A mural of Jim Morrison by Jonas Never aka @never1959 is seen at the Ellison estates in Venice on March 01, 2021, in Los Angeles, California.

According to reports at the time, Morrison had been drinking heavily that day, already missing his flight from Los Angeles to Miami. By the time he turned up to the venue, he was steaming. Stumbling his way through songs, forgetting lyrics, he cursed at the crowd, calling them “idiots” and “slaves.” Later, reflecting on his conviction, he admitted, “Miami blew my confidence, but really I blew it on purpose.”

Agreeing that the trial made Morrison realize he needed a reset and led him to seek solace in Paris, Chewning says the trip was “kind of what he needed.” “He actually said, ‘Maybe I was ready to be done,’” she shares. “He was quite drunk and who knows what he was saying. But he said himself, ‘Maybe I wanted this to happen, so I could be done for a while.’”

Chewning learned of Morrison’s death through the radio, first believing it was a rumor. She was devastated by the loss and his quick burial. “Jim was always my big brother,” she says. “For me, my hardest birthday was 28 because I thought, ‘Now I’m older than my big brother.’ It wasn’t 30 or 40, it was that moment. I think to myself, I’ve had such a full life and his was cut short.”

Morrison’s relationship with his family was tricky. Brought up in a military household, his father George, who served as an admiral in the U.S. Navy and died at the age of 89 in 2008, couldn’t quite understand his son’s music career, Chewning maintains. After Morrison left Florida and headed to California to study film at UCLA in 1964, he began saying his parents and siblings were dead, describing himself as an orphan.

Chewning believes Morrison told that lie to keep his counterculture lifestyle separate from his reserved, clean-cut family. “It was always my belief that he did it to protect my dad who was moving up in the Navy, and to keep his life separate, not to shake it up on both sides,” she says.

“My dad was kind of a classist; he didn’t go far outside of his range. When he left the Navy, he studied ancient Greek so he could read the Bible. He really didn’t understand the music. People used to say, ‘It’s just noise.’ He knew [Jim] was famous, and my mother kept a whole stack of newspaper articles and magazine articles about Jim. They were paying attention, but they didn’t get it.”

A group of people gather to pay homage, on July 3, 2011, in front of singer Jim Morrison's tomb at the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, 40 years after Morrison was found dead in a bathtub in his Paris apartment.

Chewning insists that the family’s relationship with Morrison was relatively fine. She recalls sending Morrison care packages when he was in college, including some button-down shirts. “I thought they were cool, but of course he probably thought they were horrible,” she says. “I’m sure he just laughed.” Pointing to the high cost of cross-country phone bills, Chewning says it was perfectly normal not to keep in constant communication. “When I was at school in Florida, I don’t think I talked to my parents once on the phone for nine months,” she says.

“We weren’t in close contact but when he was in L.A., we went to see him a few times. I assumed when he got back [from Paris], we would see him again. Pamela called my dad after she got back to America after Jim had died and she said Jim had been talking about coming to see the folks,” Chewning adds. “But there just wasn’t time to complete… to finish things.”

“A lot of people don’t realize it, but in his will, he gave Pamela everything, but if she were not to be alive, it was supposed to go to my brother and me. So, he still cared about us.”

For Chewning, going through her late older brother’s writings was bittersweet. She was amazed at the vast sum of writings he completed at such a young age. But it’s what Morrison envisioned for his future that touched Chewning the most.

Lisciandro was able to create a sort of loose autobiography by weaving together lines from Morrison’s journals. The young musician reflected on bouncing around from city to city during his childhood, wondered what happened to the lost notebooks from his youth, compared his nasally vocals to Elvis’ “mature voice,” and admitted using alcohol as a coping mechanism.

But there were glimmers of hope, as he also wrote about his “desire for family” and wished for “a chance to write my Paradise Lost?”

“Doesn’t that break your heart?” Chewning asks, adding that she’d never heard him speak about wanting a family of his own, but that he was always “very sweet with children.” “He was still so young. Where he was in his life, it wasn’t the time yet, but who knows.”

In a haunting conclusion, Morrison seems to contemplate leaving music behind completely, wanting to transition into filmmaking and be taken seriously as a writer. “End w/fond goodbye & plans for future—not an actor, writer-filmmaker,” he writes.

“Which of my cellves [sic] will be remember’d. Goodbye America, I loved you.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.