Jerry Bruckheimer, Viola Davis and THR’s Producer Roundtable: “I Don’t Want to Go to My Grave Saying I Wasn’t Brave Enough”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

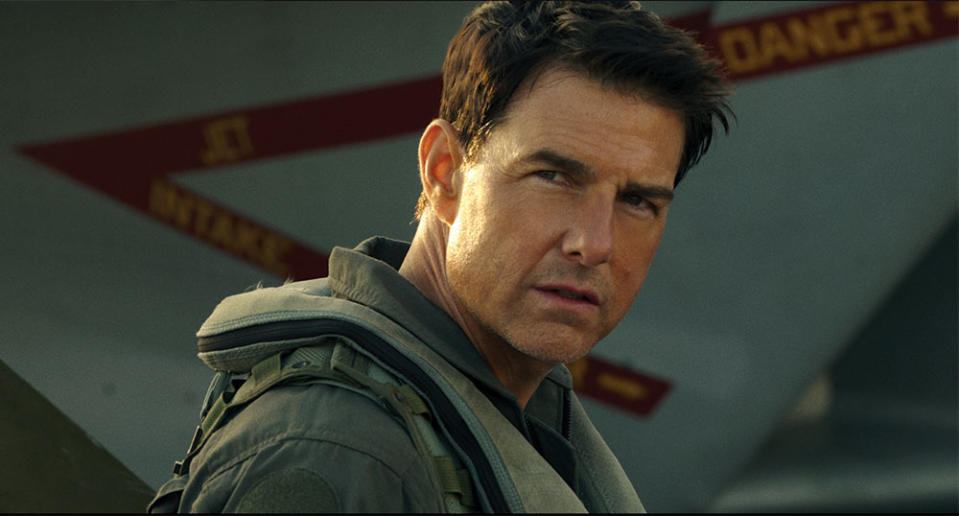

From getting phone calls that Tom Hanks had contracted a then-little-understood disease called the coronavirus to learning that the lead of their movie was in a hospital-bound ambulance after an on-set accident several states away, these producers had to navigate nerve-racking situations on their movies’ journeys to the big screen. Gail Berman (Elvis), Jerry Bruckheimer (Top Gun: Maverick), Viola Davis (The Woman King), Kristie Macosko Krieger (The Fabelmans), Nate Moore (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever) and Jonathan Wang (Everything Everywhere All at Once) came together in Los Angeles for THR‘s Producer Roundtable.

How would you describe the job of a producer to a 5-year-old?

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Oscars: Film Academy Creates and Fills New Position of Chief Membership, Impact and Industry Officer

'Beau Is Afraid' Ignites 2023 Art House Box Office With Near-Record Opening

'The Porter,' 'Sort Of' Take Top TV Prizes at Canadian Screen Awards

JONATHAN WANG It’s just on my mind because I’m under construction on my house, so I would say it’s like a general contractor. You’re going to hire vendors. You’re going to communicate vision. You’re going to make sure you are creative and logistics, all in one. Beat that, guys.

NATE MOORE I actually use the contractor comparison a lot. It’s knowing the bigger vision of what you’re trying to build without necessarily being an expert at any part of it. I’m not going to hammer the nails, I’m not going to paint the walls, but I know what we’re trying to achieve.

VIOLA DAVIS I compare it to an interior designer, because they have an overall vision and scope objective of what they want. And then they find the curtains. I also compare it to Morgan Freeman in The Shawshank Redemption when he says, “I’m the guy that they come to to find things.”

What was the scariest moment on each of your projects and why?

GAIL BERMAN I think most people probably know what the scariest moment was in our project: When Warner Bros. picked up the phone and called me and said, “Tom Hanks and Rita [Wilson] are both sick with the coronavirus.” It was a few days before we started shooting. Nobody really knew what that meant. And then they said, “And you can’t tell anybody.” That’s, like, the hardest thing anybody could ever say to me. (Laughs.) A few hours later, that became something the world found out about.

WANG I remember specifically when Tom Hanks got it, the world went, “Oh, this is real, and we have to take it seriously.” We shot for 38 days before we heard [about the] landfall of COVID in the U.S. in Seattle and New York. We were at our 35th day, and then the virus ramped up so fast that I had to make the decision to be like, “We’re going to have to shut down this production.” That was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. So, 38 days into the shoot, we shut down, and then the following Monday, the world shut down.

DAVIS We shut down for a month. Listen, with The Woman King, there was no precedent for anything. You have a movie that’s predominantly Black-female-led. There is no male lead. We’re not in G-strings rolling down poles. We’re in dirt, not looking like any sort of bastion of male desirability. So here we are in South Africa shooting what was supposed to be a few months, and then all of a sudden more than 200 cast and crew come down with omicron. And it was happening rapidly. Like, one day there would be two people, the next day 25, and it just started growing and growing until we just shut it down. We were right into the fight scenes, and we trained for the fight scenes for three months, five hours a day. But miraculously, we made it happen.

JERRY BRUCKHEIMER It’s always when it opens for me. For us, it was 35 years between the first movie and the sequel. You put all this time, this energy into this, and then you hold the picture for two years and it’s sitting on the shelf, and then you open the movie and you have no idea if people are going to accept it. The audience walked into that movie with their arms folded. They said, “We love the first one. Come on, you just can’t do any better.” And then as the jets started taking off and they heard the music, their arms kind of went to their side. But that is always the scariest thing: You work so hard on these movies, and then you’ve got to give birth to your baby and it’s not up to you anymore. It’s up to the audience and, collectively, they’re all geniuses. We think we know what we’re doing. We really don’t. I don’t care who you are, if you say you just made a hit movie before it hits the theaters, you’re lying. I’ve been on pictures where they tested through the roof. They were phenomenal. Right?

DAVIS Yep.

BRUCKHEIMER And nobody showed up.

DAVIS Yep.

BRUCKHEIMER You can have all the good intentions, you can have all the good press, or you could have all the bad press. When we did Pirates [of the Caribbean], we had terrible press. “How are you going to make a movie about a theme park ride?” Two of them before were failures: Country Bears and Haunted Mansion. They were both flops. Then we go out and the picture’s successful. You just don’t know.

MOORE Panther was a tough one to get to the screen, but the scariest moment was actually when Tish [Letitia Wright] got injured. We were shooting some second-unit work [and] some stunt work in Boston. The full crew was still in Atlanta, so I got a call in the middle of the night from the ambulance. That is terrifying because it’s not just about the movie at that point, it’s about a person, and a person I’ve known for years. As a producer, you feel responsible for everybody in your crew. You feel responsible for having her in that position in the first place and picking up the pieces. Figuring out the schedule was almost the easier part than figuring out how to get Tish’s head right and to get her the help that she needed, both physically and mentally. That was a huge, traumatic thing for her to go through. To make her comfortable to come back and perform at the level that she was performing — you don’t know if you’re going to come back from that, to be quite honest, but she did.

Kristie, I see you nodding along to all of this.

KRISTIE MACOSKO KRIEGER We shot in the middle of COVID, so there were vaccines, but you wake up every morning going, “Who has COVID today?” And you go to bed every night going, “How do we keep people safe from COVID tomorrow?” You get a phone call at 3 in the morning and the caterers have COVID, so what are we going to do for breakfast in two hours? So you buy breakfast burritos for everybody, and you figure out a new catering staff, and you just have to keep going.

WANG There are so many times that we’re like, “How are we going to solve these major problems in our world?” And then when it came to our doorstep, our industry adapted. None of us had any conversations about it, but we all figured out how to do it. We all did it individually, but collectively.

BRUCKHEIMER As long as you have money, you can solve a problem.

DAVIS If you have the money and the desire to solve the problem. When it comes to making movies, I always say, “Everybody just wants to make the movie. There’s too much money involved, so they’ll figure it out.”

Viola, you have talked about getting a lot of no’s at studios before getting one yes on The Woman King. How did you get that yes?

DAVIS Let me take a breath first. (Inhales deeply.) Here’s the thing. Maria Bello pitched the movie to me when she gave me an award at the Skirball Center — instead of giving me the award, she had the treatment for the movie, so she pitched it to the audience: “Wouldn’t you like to see Viola Davis in The Woman King?!” And everybody cheered. And I was like, “That’s some bullshit. Who’s ever seen anything like that before?” I certainly hadn’t. I don’t think, up until that point, I had been the lead in a movie. I was doing a TV show at the time. So to make a long, long story very, very, very, very short: The reason why it’s hard is because all of the characters are Black females. There are no stars. There are no white male stars. There is no big Black male star. There is not a name in front of it that says it’s going to make money and that it deserves to get a proper budget. You’re taking it to the studios, going, “We have an idea of a movie that’s set in 1826 with me, Lashana Lynch, Sheila Atim, Thuso Mbedu!” And they’re like, “Who?” And then you’ve got to get a director that the studio approves. What big director is going to direct The Woman King? You’re going to have a lot of great, really top white directors who are like, “I don’t want to touch that because I don’t want to deal with the controversy of directing a predominantly Black film.” So we’re not going to touch it, but we won’t say we won’t touch it yet. We’ll say we’re going to touch it because we don’t want to be mean. Then that takes the longest time, to go back to the director and get a definite no. Then you have to go to the directors who are available, who want to direct it, who can direct it, who are Black, but they don’t have the studio approval. So then you have to fight for that. Everything is a fight. And then, like Jerry said, the movie comes out and you’re praying it works because of all the obstacles placed in front of it. It’s the feeling that if it doesn’t work, there’s no other Black female that can do a movie after this and lead a global box office. It takes on a larger responsibility.

KRIEGER But were you so thrilled [after] opening weekend? You must have been like, absolutely, “Hot damn!”

DAVIS Absolutely. I’m happy that we got it made. I’m grateful for Tom Rothman. I’m grateful for Nicole Brown. I’m grateful for anyone that gave a yes vote. You just don’t know the price you have to pay to get into the party.

BRUCKHEIMER It’s interesting you talk about all the trials and tribulations. We all went through that.

DAVIS All of us.

BRUCKHEIMER But the reason the six of us are here is because of the emotion in our movies. [Viola] went through all of these things, like training, and we had our actors three months in different types of jets so they could handle the G-forces. They were hammered in the first [Top Gun]. Every one of ’em threw up, except for Tom. We couldn’t use any of the footage. So Tom designed something where [the actors] first started in a prop plane, and they went to an aerobatic prop, then they went into a jet, and then they went into the F-18. And there was only one person that didn’t throw up through the entire process, and that’s Monica [Barbaro]. All the rest of them, they were throwing up in the planes. They had to wipe their faces because the cameras were on. They were up [in the air] for up to two hours. They had to redo their makeup. They had to figure out where the sun is in the sky. And when they came down, the director and Tom would look at the footage and say, “Go back up.” They went through hell, just like you. But it’s the emotion. It’s what you feel about these characters when you walk out of the theater and what you made the audience feel. And that’s why all of us are here right now.

How do you convince a studio that all of that is necessary to get that emotion?

BRUCKHEIMER You have a secret weapon called Tom Cruise. I don’t know if any of you work with him.

DAVIS I have.

KRIEGER I have.

BRUCKHEIMER He’s a force of nature. Nobody cares more. Nobody works harder. And all of us work very hard.

Kristie, Steven Spielberg has talked a lot about the time he met John Ford, but what was the hardest part of actually reproducing that moment?

KRIEGER I mean, it was getting John Ford. Like, who is going to play John Ford? We couldn’t figure it out. Mark Harris, Tony Kushner’s husband, said, “How about David Lynch?” Steven called him on the phone and [Lynch] said, “Oh, no, thank you very much. I’m not interested. I’m not going to do that.” Steven said, “OK, I’m going to call you back in two weeks and you’re going to let me know.” Steven called his friend Laura Dern, who’s friends with David Lynch, and Laura Dern went to David. Two weeks later, Steven picked up the phone and [Lynch] said, “OK, I’ll do it.” And he said, “I want you to send me the costume. I’d like to wear it for two weeks before I shoot.” So our costume designer sent his costume, put it on his doorstep, he put it on. Two days later, somebody called from his office and said the arms are a little short. They put the bag on the doorstep. They fixed it. We never saw him on set until the day he shot. He showed up in his costume. It was well-worn.

Gail, you were also making a movie about an incredibly well-known figure: Elvis. What was step one in telling that story?

BERMAN Part of the problem was that he wasn’t so well known. Everybody had an image. Everybody had something to say about it. Everybody thought he was somebody from Vegas, but nobody knew the story. When I went to see [director] Baz [Luhrmann] about it, the idea wasn’t to do Elvis, let me be clear. The idea was Baz doing Elvis. That was the idea I went to him with. I thought, “Who could tell this story?” Somebody who could look at the country as an outsider. Somebody who knows how to make music a central part of their movies. The first time I sat with him, he literally pitched out the movie to me. The movie that you saw in the theater was the movie he pitched me 10 years ago. It was a remarkable story because it was a story about America. It was a story about this young man and his journey. And it was also a story told in what Baz would say was an Amadeus-like style, with Elvis as Mozart, if you will, and Colonel [Tom Parker] as Salieri.

Jonathan, Everything Everywhere has so many complicated sequences and set pieces that you were producing on a very tight budget. Taking a look at one: Raccacoonie, which is a take on Ratatouille but with a raccoon voiced by Randy Newman. How do you go about producing something like that?

WANG I’ll start by saying that the Raccacoonie character is an homage to my dad. My dad’s from Taiwan, and anyone who has Asian parents knows that they are famously bad at movie titles. My favorite one of his is, “Let’s go see Outside Good People Shooting.” What do you guys think that movie is?

KRIEGER Good Will Hunting?

WANG Yeah! You are honorary Taiwanese now! It was an homage to [co-director] Dan [Kwan]’s mom, my dad, because they would just butcher these movie titles. The premise of the movie is that in the multiverse, everything exists, so if she thinks of a world where raccoons are puppeting a chef, which is the bizarro Ratatouille, it exists. But to answer your question — the how. I love that [Jerry] said if you have money, you can get things done. We had $14.3 million to make our movie, so we had no money. Daniels [i.e., Kwan and Daniel Scheinert] and I come from the Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry and arguably the Jordan Peele background, where we had smaller scale; we could cut our teeth with our crew and learn a shorthand and put in our 10,000 hours. So we made Swiss Army Man for $3 million, and when we got Everything Everywhere, it felt like a big amount. But we still made Everything Everywhere like a music video. [Kwan, Scheinert and Wang have made many music videos together, including Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What.”] We would often say “quantity over quality” for the sets. It was [then about] training our crew, who are so used to covering their ass. As my grandpa said, “If you use both your hands to cover your ass, you can’t get any work done.” So we were just trying to let everyone know [to] calm down. It’s going to be quantity over quality for a lot of these [scenes]. These few we have to be very good at, but we’re going to spend all of our resources there, and these [are] just rapid-fire. The biggest praise has to go to Michelle Yeoh. Without her tethering us back to the heart of the film — as you said, the emotion of the film — it would’ve been a jumbled mess.

Speaking to the heart of films, Nate, you had a particularly difficult situation on Wakanda Forever. Ryan Coogler has talked about being in the middle of scripting when you all learned of the death of Chadwick Boseman. At the same time you are personally grieving someone you knew and worked with, you are now tasked, professionally, with producing an entirely different film.

MOORE Look, it was hard. We were in prep on a movie with T’Challa as the centerpiece, and Chadwick’s passing was a surprise. You’d have all the conversations you’d have when you lose anyone, right? “What do we do? How are we going to get through this?” And we couldn’t get through it together. We couldn’t be in the same space and mourn him. We had all the conversations you’d expect to have. “Should we even make this movie?” Ryan and I especially had grown really close to Chad over the years. It felt weird to consider a movie without him because he was so much a part of that character. Then we really thought about it and talked to Simone Boseman, his wife, and realized on our own and collectively that Chad would’ve wanted us to continue. I say this all the time: He knew more than all of us what Wakanda could mean to people, if we got it right the first time. And [the first Black Panther] wasn’t the easiest to make, either. There were times where Chad would come up to Ryan, who would be in the dumps about any given thing, and say, “Hey, man, don’t worry about it. This is our Star Wars.” Chad was investing so much of his spiritual energy into that film, and to not have him in this film was terrifying. That’s why recasting also was never a consideration. We would be doing anybody a disservice, frankly, to say, “Hey, stand in those shoes.” You can’t stand in those shoes. Then it became a question of: How do you reconceive a movie but also keep the crew together? It’s a credit to the crew, who all, for the most part, had been with us on the first movie. Even when we couldn’t get them answers [as] to what the movie was going to be, because we didn’t know — we were finding it out — they continued to work on the things they did know.

You talk beautifully about creative partnerships. You’ve each worked with actors, writers, directors and crewmembers time and again. When you find a lifelong creative collaborator, how do you know?

BRUCKHEIMER “Show me” is what it is. Hollywood is so full of fantastic salesmen. They can sit in a room with a writer or producer or director and spin you a tale, and when they’ve got to put pen to paper, it’s a whole different story. You find that out quickly. You want something special and interesting on that screen, because we’re all competing against each other. Can you help create something that’s special that audiences will embrace and pay money for?

BERMAN Well, Jerry, we were very happy that [Top Gun: Maverick came out] before us, because it showed us that adults would come back to theaters and watch a movie. We were in your wake.

BRUCKHEIMER We found that initially our audience, which was older, hadn’t been to the theater for two years. And that movie kind of drew them out.

WANG I think oftentimes we want to define ourselves by these really narrow groups. We want to say, “We’re this, we’re that, and we’re against that.” But to your point, your film opened up this space for us to be able to thrive. And big, huge studio films and independent films are great bedfellows. They speak to each other. But at the heart of it, we still needed to get that emotion. It was shocking to see how many people have come up and said, “I was thinking about getting a divorce. We were fighting in the car on our way to the theater. We watched your movie, and we’re not going to get a divorce.” It’s not even being hyperbolic. The amount of people who came up to us crying after a screening — it’s almost like, I’m not equipped to be a therapist, but I’m having to console someone to say, “I see you and I’m with you in this, and we all are experiencing our trauma.”

DAVIS Uta Hagen, the famous acting teacher, said, “The mark of any great art, whether it be theater, whether it be film, is that when you walk into the theater, you have a human experience.” All of these films right here — like you said, Jerry — they moved people emotionally, collectively. But no matter what, if you walk into a studio and … for instance, you are a wonderful actor who is disabled but has a really great story. Or you are a woman of a certain size and age, and you’re a dark-skinned Black woman, and you have a great story. Selling that story in the room is really hard. Even if the nucleus of that story is one that every human being feels, you are going to have a hard time selling it because of the player. When I have a collaborator, the two things I look for is ability and bravery. The bravery of knowing that whatever is on this page, we’re not going to water it down, we’re not going to hustle, we’re not going to barter, we’re going to keep it absolutely the way it is. And we’re going to sell the shit out of this. That’s my husband: We are going to ride this into the ground until we get a yes. What does not go away, creating any sense of art, is rejection and impostor syndrome. Fear. The fear that it’s not going to work. I look for bravery all the time. I don’t want to go to my grave saying I wasn’t brave enough.

You need the buy-in, so the audiences are able to see it too.

DAVIS Truth is bravery, and a lot of times we don’t get truth on that screen. We’re afraid that that person who’s drinking that Diet Coke, [eating] Sour Patch Kids and popcorn, is going to get up and leave. It’s too much truth for a Saturday night. But when you really go for it — which I think is the reason why we’re all here — when you really go for it, that is a sweet spot. Feels like church.

What were the movies that first inspired that emotion and made you say, “I want to do that too”?

MOORE It was The Goonies. It is a movie that transports you to a different place and you go, “Oh, I want to do that for someone else.”

WANG And thank God Data [played by Everything Everywhere star Ke Huy Quan as a teen] is back.

MOORE That’s right, he’s back!

WANG I always brand it as if a movie has umami. It’s not sadness, sweetness or fear. It’s this other thing that sticks to your bones. For me, it was Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

BERMAN When I went to Paramount Pictures, and all the press was like, “This TV girl got to Paramount Pictures? The whole world is going to blow up!,” they [asked], “What’s your favorite movie?” I was like, “It’s The Godfather.” By the way, I love The Godfather, but what I wanted to say — and I was able to say to some people who weren’t as critical of me — was “every melodrama that I watched at 4 o’clock in the afternoon when I got out of school that would come on after Another World.” I watched them every single day. I learned from my couch in Bellmore, Long Island, New York, and not in film school.

KRIEGER I love all the John Hughes films. Those were, for me, my childhood. [His characters] are what we aspire to when we make all of our films. They are just great characters that you can rely on.

DAVIS The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman changed my life. It made me go to a place in my imagination where I could be anything. I didn’t know that that existed. I thought that the world put a stamp on you and that’s exactly who you were. And all of a sudden, I saw the magic of transformation with acting.

BRUCKHEIMER I’m the last one? I think I’m the oldest, too.

BERMAN Not by much, Jerry.

BRUCKHEIMER It was always about character, and it was Bridge on the River Kwai. David Lean is somebody that I thought was a master visualist and master storyteller. That’s why you went to the theater. You wanted to see these big, character-driven dramas, on that big screen, in worlds that you’re not a part of.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

This story first appeared in a Jan. stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

'The Super Mario Bros. Movie': See Who Voices the Beloved Characters

Hollywood Reporter Critics Pick the 50 Best Films of the 21st Century (So Far)

Hollywood Flashback: 'Soylent Green' Depicted an Overpopulated Planet With a Dark Secret