Jermaine Dupri’s So So Def Records 30th Anniversary Proves Longevity, Surviving The Times and Hit-Making Equals A Hall of Fame Legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Duality can be a gift and a curse, pending from what side of the coin you view it.

For Jermaine Dupri Mauldin, that gift side has afforded him great success, to the tune of more than 400 million records sold (and counting) while traversing between the world’s of Hip-Hop and R&B. Yet, that ability to navigate various realms of the curse side has been seen as a hindrance. Or even worse, a weakness. And for the man who proclaimed “Money Ain’t a Thang” on his breakout rap single 25 years ago, that has left enough chips on his shoulder to rival the largest casino bank in Sin City. You see, despite boasting one of the most impressive resumes of any songwriter or producer of his generation, with hits under his belt that have likely kept you partying til the morning, folks continue to sleep on Jermaine Dupri. You think we’re reaching? Take it from the man himself.

Speaking with VIBE via phone days prior to his 51st birthday, he laments the notion that he hasn’t been attributed the proper credit for many of the songs he’s helped write or produce. In this particular case, he bemoans that fans, and even friends, were oblivious to the fact that the production on JAY-Z’s 2007 American Gangstar album standout cut “Fallin'” was crafted by his hands. “Ni**as is actually calling my phone like ‘Yo Jermaine, I can’t believe you made this record,'” he says, in apparent disbelief. “How many records… how many hit records do I have to make before you stop saying ‘I can’t believe you made it.’ It’s really crazy because in 2023, ni**as is still saying that.”

In the multi-hyphenate’s defense, he has a point, as the Billboard charts and credits don’t lie. Having written and scored hits for Mariah Carey, Usher, Destiny’s Child, and TLC, he’s played a hand in the creation of nearly a dozen No. 1 records on the Billboard charts. He is also the only producer to secure the top three slots on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart at the same time, a feat he accomplished in 2005.

On the chart dated August 25, 2005, Mariah Carey’s record-setting single “We Belong Together” hit No. 1, with Bow Wow’s duet with Ciara “Like You” peaking at No. 2, and Carey’s “Shake It Off” trailing in third. If that wasn’t impressive enough, he narrowly missed having five records in the Top 5, as Bow Wow’s hit “Let Me Hold You” fell to No. 6 after placing at No. 2 the week prior. Add in the fact that he nabbed his first chart-topping record at the tender age of 19 with Kriss Kross’ seismic, trendsetting debut single “Jump” in 1992 and what you have is a prodigious talent that long showed a proficiency for making moves, as well as helping adorn musical royalty with some of their crowning achievements.

Born in Asheville, North Carolina in 1972, Dupri first showed promise as a dancer. He found his way to the Fresh Fest stage as an opening act during the mid ’80s mega Hip-Hop tour via his father (a production manager for the tour), Michael Mauldin. Befriending producer Chad Elliott during his time on the road, Dupri received what he describes as his “Hip-Hop Crash Course” while visiting Elliott in New York City at the height of the genre’s first golden era. “I just wanted to be a part of it so bad,” the boardsman shared of his cultural aspirations. “Nothing was gonna stop me.” Bitten by the Hip-Hop bug, upon returning home to Atlanta, Dupri sought out local female rap trio Silk Tymes Leather, writing and producing material for the group, helping secure them a deal with Warner Bros. Records.

Yet, it would be the burgeoning music man’s second finding that would put him on the map. In 1991, Dupri discovered kid-rap sensation duo Kris Kross at an Atlanta mall. J.D. cultivated their unique backwards clothing for mass consumption while penning and producing the duo’s 1992 debut album, Totally Krossed Out. Earning Kris Kross a deal with Ruffhouse Records, the group instantly became one of the hottest acts in music, with their debut single “Jump” skyrocketing to No. 1 and Totally Krossed Out, certified multi-platinum after selling over four million copies in the U.S. The youngest producer with a chart-topping record at that time, Dupri suddenly became the talk of the music industry.

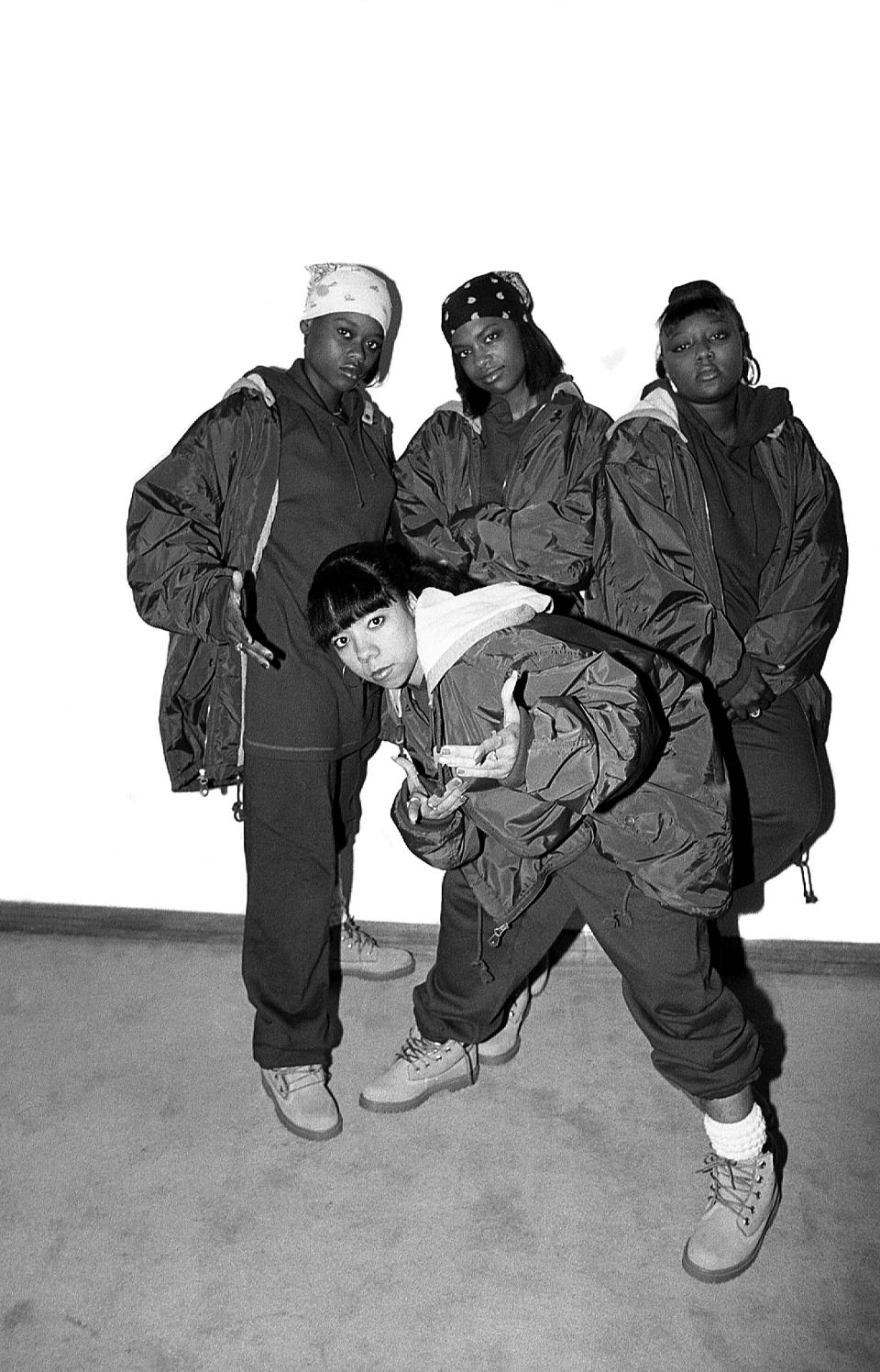

For all of the success he would find over the course of three decades, his biggest contribution came with the launch of his own record label So So Def in 1993. At a time when Atlanta and the South had yet to fully find its footing, not only for musical talent, but the music business, So So Def quickly stood tall as a force to be reckoned with. Introducing platinum R&B quartet Xscape and groundbreaking female rapper Da Brat, the label was among the most popular in Hip-Hop and R&B, with acts like Ghost Town DJs, INOJ, and veteran rap group Whodini helping fill out the roster. After years of contributing vocals on records, Dupri stepped into the spotlight in 1998 with his own solo debut Life in 1472, which sold a million copies and minted him as a star in his own right.

Over the subsequent decade, So So Def housed platinum-selling acts that impacted the airwaves and infiltrated the hearts of fans. Jagged Edge, the rugged vocal quartet out of the A asked the question we all have pondered on their chart-topping R&B smash “Where the Party At” and are responsible for arguable the most ubiquitous wedding song of the past quarter century.

The young pup that grew up into a man before our eyes, Bow Wow found success off the kid-rap blueprint of Kriss Kross, but took things a step further, solidifying himself as a bonafide hitmaker and one of the biggest rap stars of the ’00s. Soulful crooner Anthony Hamilton helped bridge the gap as the So So Def transitioned into a new era following its first decade in the game, hallmarked by successful signees like YoungBloodz, BoneCrusher, and Dem Franchize Boyz.

Accounting for millions of albums sold and timeless classics, the label remains a legacy brand in music, with many of its artists still recording music and touring across the country and globe. But the ride has come with its adverse moments. Beef with his peers. Relationships gone awry. Fallouts with artists. Adapting to a changing industry and musical landscape.

You name it and JD has probably experienced it. But one thing the Grammy Award-winner remains definitely adamant about is that he’s no longer taking shorts. Having released For Motivational Use, Vol. 1, his 2023 collaborative album with Curren$y, fostered relationships with some of the brightest young stars in R&B, and with numerous celebrations of the 30th anniversary of So So Def on the horizon, by no means is Dupri done making history.

So So Def and JD’s genesis also coincided with VIBE’s, as we are also celebrating 30 years of impacting Black music and culture through reporting and documentation. We’ve witnessed the highs and lows and have put many, if not all, of his most trusted collaborators on the cover, at one point in time. Ironically, Dupri has never been on a VIBE cover, making this his first. But the timing couldn’t be any better, as he’s ready to let loose and put the world on notice. And in spite of his duality, one thing’s for certain: his place within the Black music pantheon cannot be denied.

For VIBE’s 30th anniversary issue, Jermaine Dupri spoke with VIBE about 30 years of So So Def, his illustrious career as a mogul and creative, making Atlanta a hotbed for Hip-Hop, rivalries with fellow hit-makers and what’s next.

So So Def was originally a production company that was successful off the strength of Kris Kross’ debut Totally Krossed Out. What spurred you to transform So So Def into a record label?

When I did the Silk Tymes Leather record, I was 16. It was the first time that Warner Brothers had ever had to deal with a songwriter and producer of that age. And I was the person telling everybody what to do at 16. So what I knew was that I wasn’t great at what I was trying to do. Two, this is my first time doing it, so I wasn’t gonna try to do everything. I was going to do the producing and the writing. I asked my Dad to be their manager, that’s how he got into the music industry.

My dad got a company with a guy named Phillip Calloway. They got a deal for Silk Tymes Leather with Warner Bros. They had never dealt with a producer of this age, so they they decided to put me with Joe Nicolo, who was Joe The Butcher. And Joe The Butcher became the owner of Ruffhouse Records. That’s the only reason why Kris Kross was on Ruffhouse because I didn’t know nobody else. I didn’t want to go to Warner Brothers ’cause I didn’t think they did a great job with Silk Tymes Leather, but still, I went to somebody I felt like knew me better.

Before this deal happened, I’d never even thought about having my own label. The label situation came from me having to deal with Sony once Kris Kross came out. I started realizing like, ‘Wait a minute. I’m telling everybody at this label what to do. The group is successful and all of these adults are doing everything that I’m telling them.’ So I’m telling them what to do and at this time, you’ve never seen nobody that young in record companies in 1991. When I saw that I’m like, ‘You know what? I’ll set up my own label because I’m telling you guys what to do.’

So once again, it was like a big idea. It wasn’t something that was etched in stone. The idea was like, ‘Okay, yeah, I can have my own label. Let me get my own label.’ And Kris Kross had sold so many records so fast and Columbia had just lost Def Jam, so it was perfect for me. Columbia actually needed another source of music. They didn’t know if I was gonna be that person, but they saw what happened with Kris Kross. I think Columbia had just lost the whole Def Jam catalog. So they lost all of that and I think it just made sense for them to be like, ‘Okay, look, we got a guy here that looks promising.’ Kris Kross, I think was at two million [records sold] on “Jump” and it became the fastest selling single that year. So they offered me a situation to make more music and once they said it, I already had it in my head that I wanted a label. And that’s how we got So So Def.

What was your vision for So So Def as you were putting the pieces in place?

I knew that it was gonna probably be hard already coming from Atlanta trying to be a rap label. Atlanta wasn’t known for rap and this was at a time where the South getting the opportunity to do anything in Hip-Hop was unheard of. So I decided to sign these girls that I had saw come to my house for a birthday party prior to Kris Kross. Xscape came to sing [me] happy birthday. When they sang happy birthday, I told them ‘You know what, I’ma sign y’all.’ I was just talking big sh*t. I’m just thinking if I ever got an opportunity to sign these girls, I was gonna sign them. And lo and behold, Columbia offered me this deal.

I got the deal, I signed them. I was like ‘This is an R&B group. If I could break them, my label won’t be pigeonholed as a one trick pony.’ So I wanted to do an R&B group first and then come back with more rap. So that was the move and the plan I tried to make happen.

By 1995, So So Def was a powerhouse, but you were only 22 at the time. How did reaching that level of success at such a young age affect you?

I think it affected me good and bad. [It was] both sides because I didn’t have teaching or anything like that, but I never got in trouble or a situation where I needed a person to come bail me out. But yeah, I was pretty much just moving the needle myself. Nobody was showing or telling me what to do.

I had my father, but he basically got in it the same time that I got in. We was just moving at the same time, so a lot of it was good. I had a couple of bad things that could happen, but for the most part, it was just a learning experience.

Given your proximity to LaFace Records in location (ATL) and sound, was there a rivalry on your part to compete?

With me, it definitely was a competitiveness on my side. I don’t know about their side, but it was definitely competitiveness on my side. I looked up to Russell Simmons. When I got my label, I wanted So So Def to become the Def Jam of Atlanta. That meant I wanted to have an office, but I wanted So So Def to be synonymous with Atlanta as the label that’s from Atlanta. Just like Def Jam became the label from New York. So when LaFace came, I felt like ‘They’re getting ready to try to take over what I’m doing and they ain’t even from the city.’

That was my mentality. And strangely enough. I thought that LaFace had a better deal than me when they came to Atlanta because they moved their whole operation to Atlanta. I just found out like two years ago that my deal was still bigger than LaFace deal when they came to Atlanta. I never really knew that. But I felt it was because their presence of who they were. The way people was treating them was much different than the way I was getting treated.

You pursued your own career as a rapper, releasing your debut album Life in 1472 in 1998. How did that evolution occurred?

The Da Brat record, “Funkdafied,” became a platinum single. It became such a huge success that I had to perform the record with Da Brat all the time. I was out in the mix being an artist more than I was at home being the CEO of a label. So that song carried me into my own album. Once people heard me rapping and I would do interviews with Da Brat, people would ask me, ‘Jermaine, so we hear you rapping on this song, you’re gonna make an album?’ But I was making so much music and I was writing songs. Songs that I was writing, I was throwing them away.

And I start seeing my friends wanting to hear my demos and wanting to listen to what I was doing. So then I was like, ‘You know what, f**k it. What’s it gonna hurt?’ And then I thought about another person who was my idol, Quincy Jones. He had just done Back on the Block. I was like, ‘You know what, I could do an album like this.’ I can do a rap album like Quincy Jones that’s a producer’s album. Where I rap on some songs and then I basically make all the beats on the album. I put all the big superstars on this one record the same way Quincy Jones did. So that was my mindset at that point, to just try to do a Hip-Hop version of Quincy Jones’ Back on the Block.

Was there backlash or any doubt or critics, like ‘This guy’s trying to make a rap record?’

Always. We still had to prove ourselves as a rap state and as rappers coming from Atlanta. That’s why my first single was with Jay-Z because I was in full-blown Hip-Hop mode and I wanted everybody to notice. I think people thought the first record that I was gonna come out with was gonna be like “Funkdafied.” But I chose to go a different direction and I put out a rap song. I put out a rap record because there were other things that I was caring about. Like DJ Clue mixtapes. It was shit that I was listening to that I’ve never heard ni**as from the South on. I never heard nobody from the south on the DJ Clue mixtape and I was like, ‘F**k this. I’ma be the first rap ni**a from Atlanta to be on a DJ Clue mixtape.’

I didn’t care about radio. I didn’t care about having a single that was as big as “Jump.” When I came with “Money Ain’t a Thang,” they was like ‘Why are you gonna put out this song with this guy Jay-Z?’ Nobody at Sony knew what Jay-Z was about. They knew Jay-Z was a rapper from New York, but they didn’t think that Jay-Z did anything for Jermaine Dupri. Me having a Jay-Z record seemed like nothing to them. And that’s ultimately why “Money Ain’t a Thang” isn’t as big as it should have been. Because if they knew the value of Jay-Z back then, that probably would have been one of the biggest rap records ever in history.

Hip-Hop gravitated to that record in a way like nobody else. For a person from Atlanta, Georgia to have a record like that, it was unheard of. And that’s all my goal was, to make people understand that ni**as in the South ain’t just like whatever you think they are. I’m the first person taking this step forward and the first step I took was with Jay-Z.

Back then you were making a name in the industry, but now you’re a household name and superstar. How did that change the game for you, personally and professionally?

I had to get out of that space. I was in that space and I was doing shows, then I got scared of it. I started ignoring Jermaine Dupri duties as an artist and went back to being Jermaine Dupri the producer. I didn’t go on tour, I didn’t do no shows. I didn’t do anything. I regret that to this day. I feel like little did I know, I could do it all, I just didn’t. I was scared. I was still running at a pace where I didn’t know. I saw the success of me becoming an artist taking away from me being at home in the studio. And I know that I’m a producer first. Making records and being able to continue to make records for So So Def, I didn’t want to ever lose sight of that. I didn’t want nobody else to start making the record[s] that I put out, either. So it was a decision that I had to make. I could’ve done both, I just didn’t know I could do both at the time.

Around this period, you developed a rivalry with Dr. Dre and Timbaland. Give us your version of how that started and why it went down?

You’ve got to remember, I’m still younger than all these ni**as. I still was a kid out here doing and trying to do stuff. In Hip-Hop, they weren’t used to allowing kids access to the same things that they was getting. That’s why we took a lot of those punches. They dissed me for no reason. At that point when they did it, once again, I’m a Hip-Hop guy. These guys don’t know me. They don’t know nothing about me. They just believe what I am and I retaliated the same way anybody else would retaliate. I started realizing, ‘Wait a minute.’ One thing people understand about me, I really, really pay attention.

So I started really paying attention to all of these producers and all of these songwriters and I’m starting to realize, ‘Okay wait a minute. This ni**a don’t even do this. Oh, this guy did this for this dude?’ I’m building this confidence like, ‘Oh, these guys really ain’t built like me. I’m really the person that’s in here making these beats.’ So I think I said something about Timbaland and Dre or somebody asked me [a] question. I said, ‘If you put all three of us in separate rooms. You put me in a room, put Timbaland in a room, put Dre a room, who you think gonna come out with a full song first?’ I think I asked somebody that question and that got back to them and that threw them off. That made them mad. It made them look like I was trying to [make them look bad]. Whatever it was, it was the truth. But they weren’t trying to deal with it and they weren’t trying to hear that at that point in time [laughs].

I mean, it wasn’t really no beef. It wasn’t even a rivalry. Eminem was protecting Dre and I was just protecting myself. It’s crazy cause Proof, rest in peace, he came to my studio and he told me, ‘Man, JD, I want you to holla at Em. I want y’all to talk, it ain’t even no beef.’ It wasn’t no real beef. For me, it was a misunderstanding of ni**as not understanding that people from the South ain’t just regular a** ni**as or whatever you thought they were. Ni**as in the South got just as much chops and we deserve to be treated the same way that everybody else in Hip-Hop was being treated.

Did you ever get a chance to sit down with them either of them?

Oh, yeah. I had a party at Dre’s house one night. Me and Timbaland, we basically became cool and sh*t. Like I said, it was a thing that was nothing. The more records I made, I think they started realizing like ‘Damn. Okay, this guy really ain’t what we thought he was.’ And that’s all I think it was.

I’m a name a couple of these names and I want to know what comes to mind when you think of these names. I’m gonna start with Mariah Carey. What comes to mind when you think of her?

Architect. She’s an architect of Pop and Hip-Hop music. She’s the reason there’s a Ariana Grande. She’s the reason why Taylor Swift can go from making country to pop music and it’s accepted in a way and it’s thought of [as] how to do it. Mariah was the blueprint for all of that. And it’s all her mind-state, it’s not anything else. All the ideas that Mariah wants to do and the things that she’s talked about, they’re all Hip-Hop ideas. And in her mind, she always knew that ‘I’m already a girl that can sing whatever I want to sing. If you put melodies on top of this, it’s gonna turn into something completely different.’ She was an architect of that.

How did y’all meet?

We were all on Columbia Records. She was the biggest artist on Columbia Records and what I did with Xscape’s first album interested her. And she was like, ‘Who’s the guy that’s producing Xscape? It sound like somebody I should worked with. I like the sound.’ So they called me. And Columbia had just lost Def Jam, so they were trying to make Jermaine Dupri the golden guy to go to in that building. So they was putting me in the studio with the biggest artists. So that was one of the lobs that they threw me.

Can you describe the personal relationship outside of music?

That’s my homie. It’s a real love. If we don’t make records, we’re still the same people without making music. We talk all the time. We’re always trying to make music, but for the most part, she also has a different life and I have a different life. So yeah, we’re best of friends and I feel like she trusts me. I’ve managed Mariah and all of that. So I’ve been in the space where I know she trusts. I got a hundred percent trust from her and she’s got 100% trust from me.

What comes to mind when you think of Usher?

Superstar. Hands down, just a bona fide superstar. He was put on this Earth to entertain people. Dance, sing, act, just a complete superstar. He always just needed a team of people that understood that he was that superstar. Once that happened, you see where he is now.

How did y’all first meet?

Well, Usher also was an artist that came to me first. He actually came to Kris Kross concert that I was having in Atlanta and his manager at the time, AJ, brought him. And he’s like, ‘Jermaine, I want you to sign this kid named Usher,’ and at the time I was having a back and forth situation with Kris Kross’s parents. And their parents was starting to be more involved and it just started seeming like more of a headache than I actually wanted to deal with. So I was just like, ‘I don’t want no more kid artists, I’m gonna try to get out this kid business.’ I was actually trying to not do no more kid artists. Kris Kross had worked, I was trying to go to Xscape and get the hell away from the kid business. So when Usher came, I just wasn’t on the kid sh*t no more. I was trying to be away from it. And as good as he was, I still was like, ‘You know, what? If y’all get a deal, I’ll work with him.’ That’s what I told him because I wasn’t really trying to deal with no more parents.

That was the only reason I passed on Usher. But that’s how I met Usher and then from there, they made that [debut] album. And then me, working with LaFace, they always came to me for remixes and they asked me to do a remix of “Think of You.” When I was doing the remix, they asked could I write another part because his voice was changing. And this is the first time I was producing an R&B artist solo, so none of that stuff scared me or anything. I ain’t know what was going on, I was just going with the motion. They brought Usher in, we redid the bridge on “Think of You” and I rewrote the bridge for him. And when I rewrote it and he sang the way I wrote it, he felt comfortable. I felt like it was a win-win, and I think he went back to them and he told them ‘I think you should let JD work on my next record.’ They also loved the remix and they was like, ‘You think that you could do that with him on a whole album?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah.’ And they gave me my opportunity to do his second album My Way.

Can you speak on the friendship that y’all have still to this day?

Usher is like a son of mine. Not just a best friend. Everything that I talk to him about is always for the better of him. And he understands that and he trusts that to a level that he knows when he comes to see me or we hang out or whatever it is. I’m not a guy that’s trying to live off Usher. I’m not the guy that’s trying to take pictures around us to make myself look better or anything like that. I’m genuinely there for him to make him a better person. And when you have that type of relationship and people understand both sides of the relationship, it’ll last forever.

Come Back for Part 2 of 2 as Jermaine Dupri speaks on Janet, Latto, Diddy, Verzuz and more, on October 25th 2023.

More from VIBE.com

Doja Cat Gets Serenaded By Usher During His Las Vegas Residency

Usher Gets Key To Las Vegas, City Declares 10/17 Usher Raymond Day: Watch

Best of VIBE.com