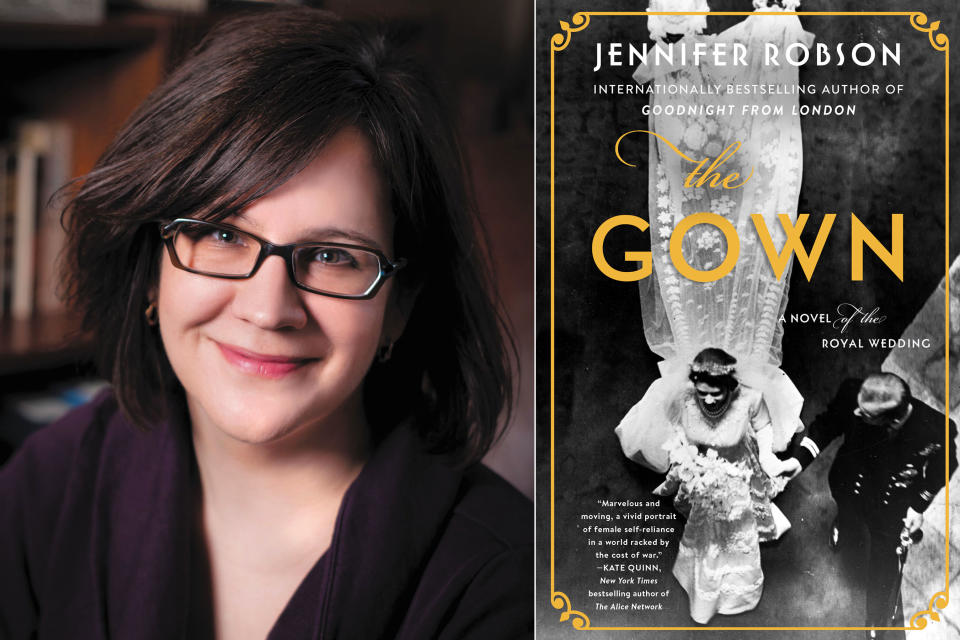

Jennifer Robson talks royal weddings and giving voice to historical women in The Gown

Jennifer Robson has particular reason to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip’s wedding anniversary this year: Her latest book, The Gown, which hits shelves Dec. 31, takes Elizabeth’s wedding gown as its central element.

In 1947 London, two women — Ann Hughes, a Londoner trying to cope with austerity measures after surviving the Blitz, and Miriam Dassin, a French Holocaust survivor — form an unlikely friendship while working as embroiderers at the house of Norman Hartnell. When the royal family gives Hartnell the commission to make Elizabeth’s wedding gown, the two women find their lives turned upside down. And in 2016, Heather Mackenzie uses the familiar embroidery motifs in the scraps left to her by her grandmother to uncover her most beloved relative’s secret past.

“If there’s one overriding reason that I write, it’s to give voices to women who lived in the past,” Robson says of her approach to historical fiction. While trying to do so for these artisans, she found herself on a journey similar to Heather’s contemporary storyline — a hunt rife with kismet and inspiration. Her quest for details took her to visit the Queen’s dress on display at the Fashioning a Reign exhibit, and to the embroidery house Hand & Lock to get a handle on the skills required to complete a royal wedding gown. As luck would have it, Robson’s visit coincided with that of a documentary crew, who pointed her to Betty Foster, a seamstress who had worked at Hartnell on the Queen’s wedding gown in 1947.

For Robson, highlighting women like Foster is why she does what she does, and she learned a wealth of necessary details during their time together. In advance of the Queen’s Nov. 20 wedding anniversary, EW called up Robson to get all the details on her new novel giving readers a rare glimpse into the invisible world beyond the public face of the royal family.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: Before you hit on the gown idea, you knew you wanted to write a novel set in postwar Britain; why that time period?

JENNIFER ROBSON: It’s a conviction that what happens after a war is often just as interesting as what happens during the war. My previous book, Goodnight From London, ends on V-E Day, and so then I thought, “What happens the next morning?” What happens is people look around and they see that their country is in ruins, figuratively and literally. Britain was more or less bankrupt. The immediate years that followed were just so grim, and it’s something we don’t often talk about. A lot of popular history skates from 1945 straight into the 1950s. Everything is suddenly in Technicolor, and women are in their crinolines, and life is on the up and up. There was this long period of people effectively being on their knees. That first step when you’re trying to heave yourself onto your feet again is sometimes the hardest step, and I wanted to capture that year. But at the same point, who wants to read a book just set in the grim, gray, dour, miserable, cold, hungry period? If you’re writing highbrow literary fiction, then obviously, the more depressing the better. I need something beyond that. Some kind of light at the end of the tunnel.… I went straight from 1947 to “What’s the counterbalance?” Globally, the news was depressing all around, but the one bright spot I could find in that year was the royal wedding.

How did you decide to focus in on the embroiderers of this gown?

What is the focus beyond the people involved with a royal wedding? It’s invariably the gown that the bride wears. I thought, “Who made it?” Because that was a question I remember having when William and Kate got married. Everyone talked about the designer, but I never saw an interview with any of the women who worked on Kate’s gown. Now, I think that’s in deference to privacy issues, but I did want to know their stories. What is it like to work on this wedding gown? How did they make it? What set [the Queen’s gown] apart was the embroidery. I knew from the beginning that’s what I wanted to capture: Who were the women who did the embroidery? And what was it like to work in those work rooms, under that pressure? It’s almost as if the gown was made out of stardust, but then they had to leave work and go home to cold, miserable houses with not quite enough to eat and wearing rationed clothes that they’d probably been wearing since 1942. What was that like? That’s what I wanted to know.

Why do you think the royal wedding in 1947 was such a huge event?

As soon as I started to dig into it, I went into it thinking there’s going to be a lot of people who are saying, “The last thing we need to concentrate on now is the royal wedding. People are starving, we’re running out of coal, everything’s rationed up the wazoo — why are we even talking about this?” What surprised me was that broadly speaking, most people really got behind it and embraced the notion. The royal family had stayed in Britain even as it was being bombed. They had stayed and done their bit. Princess Elizabeth herself was in the [Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women’s branch of the British Army in World War II]. Just the idea of her having some kind of austerity wedding, people really rebelled against that. Immediately after the announcement of the engagement, people agitated for her to have a decent wedding. Nobody wanted to see the princess go down the aisle in her ATS uniform. They wanted her to have a beautiful gown, and not to scrimp on that.

Ann loves the royal family, while Miriam is more skeptical. How do you feel about the royals?

The thing is, I have a tremendous fondness for the Queen. Very few of us can remember what it’s like to be alive before she was the Queen. The thought of the world without the Queen is very hard for me to wrap my head around. It’s kind of nice to go back to 1947, where she’s this beautiful young princess, 21 years old, and her whole life lies before her. The Queen is this real point of reference in a world that changes. I find it comforting to know she’s out there. You can privately deplore the excesses and the way tax dollars are spent and the constitutional implications of a hereditary monarchy. That aside, it is very comforting to have someone like the Queen at the helm. What I tried to balance in the book was these differing points of view that are both legitimate. It’s legitimate to love the Queen and the royal family, especially if, like Ann, you have just come through this punishing war where they were a real point of unity. But it’s also fair, if you’re like Miriam, to be really skeptical. Like, who are these people? Sitting in their palace, eating off their gold plates. Why should I care?

Can you tell us about Betty Foster and what you learned from her?

If there’s a point in my adult life as a historian and a writer that I can single out as being the the single greatest moment in terms of personal satisfaction, it was the day I spent with Betty listening to her tell me about what it was like to work at Hartnell.… I have hours of taped conversation with her, and I listened to her tell me about what it was like to work there and to make the Queen’s wedding dress. There were points where I felt like I could hardly breathe. She wad so forthcoming. She remembered everything. She had pictures and this precious scrapbook. She had scraps of the fabric from the wedding dress and the gown and the veil. She has the row of practice buttonholes that she made. Buttonholes you can’t move or change once you put them in; they have to be exactly right. There were 22 of these things that had to be lined up perfectly, and the bodice of the gown had already been embroidered, which had taken weeks and weeks. If she messed it up, I don’t know what they would’ve done. I’m not sure how they would’ve fixed that. I remember asking her, “You must’ve been so nervous.” She said, “No I wasn’t.” Because they were used to [working] quickly. They were always getting in rush orders for famous actresses. I had all these spots where I didn’t have the detail that I require of myself when I’m writing a book, and I had been so unwilling to just skate over. The book was mostly there, and I had to go back and take what Betty had told me and add washes of color. But also fix things that I got wrong. As soon as I’d done that, the book came to life.

Your book was already written by the time of Harry and Meghan’s wedding, but did the embroidery representing all the Commonwealth nations on her veil tempt you to go back in?

That symbolizes the power of something that doesn’t necessarily seem important to people, like embroidery. In choosing that veil and incorporating every nation in the Commonwealth, she made a very powerful statement. It’s a statement about the importance of craft. Nothing in her gown or veil was done quickly or sloppily. Nobody was stuffing it through the sewing machine. That was something that was made with care and reverence, and with the skill and devotion of people who spent many years learning to do what they do. And they don’t get recognized for it.… These women were artists. Just because we don’t apply that term to them doesn’t mean they aren’t artists. They are. If anything, I think we should all try and think a little bit more widely in terms of what constitutes art. These gowns to me are works of art and should be treated as the precious things they are.

The lives of women are largely missing from the historical record. Do you think historical fiction can help fill that gap?

When my female characters achieve something, [it] is because they’ve done it. It’s not because somebody else has handed it to them, which is the feminist message running through all my work. If people don’t see it, I don’t think they’re looking hard enough, because it’s there. I think to myself, “My daughter is going to be reading these books one day, and I need her to see that women were and are powerful and that our voices matter.” Women’s stories are important and matter. Just because they haven’t been told doesn’t mean they’re not worth telling.