Jeff Jensen says goodbye to Entertainment Weekly

I got my job at Entertainment Weekly because of a fire drill.

The year was 1998. I was 28 and a reporter at Advertising Age, the place that gave me my start in journalism right out of college. I covered sports and entertainment marketing; I wrote a lot about basketball shoes. I was also an unapologetic geek, pop culture obsessive, and insufferable pretentious twit with a passion for comic books, TV, and prattling on about auteur theory to my friends. I was a Christian, but I’ve prayed as much to David Lynch as Jesus since Twin Peaks ascended into heaven in 1991. Dear Almighty Eraserhead, please dwell among us again…

Okay, exaggerating. But I’m not kidding when I say that my Bible at the time was Entertainment Weekly, the curator of my cultural life, the pusher-man of pop addictions. Every Friday, I’d steal the new issue of EW from Michael Schneider’s mailbox, take an early lunch and read it cover to cover — and then return it without him ever knowing. One night, I found myself at a dinner party, sitting across the table from my favorite EW writer, Chris Nashawaty, listening to him talk about a piece he had done on the cultural significance of Godzilla. I burned with covetous envy. That sounded like my dream job. Feeling I had reached a crossroads in life, I decided to make the dream come true or get out of journalism. The other options: English professor, pastor, or open a single-screen indie theater with an adjoining bookstore/coffee bar. My soon-to-be fiancée, Amy — weighing possible futures for herself – strongly encouraged the EW idea.

I sent clips to every editor and hoped one of them would call me. Maggie Murphy did. Soon, I was meeting with Mary Kaye Schilling to audition for the next act of my life. Fail and I was teaching Kakfa 101, attending seminary, or trying to convince a bank that I actually knew something about lattes. We were a couple minutes into the interview – barely beyond pleasantries – when the fire alarm went off. It was a drill. Everyone out of the building.

Mary Kaye and I joined other staffers in the hall. We tried to continue the interview (“So, who’s in your Rolodex?” “Uh, the head of publicity at Reebok?”), but it was awkward. Enter Dan Snierson, soon to be one of my best friends in the world. He was the last person to join the line because Dan Snierson is the hardest working person in entertainment journalism, the last man out every night. As we began walking down a stairwell to a street 17 floors below, Dan and Mary Kaye started talking about Fox’s Party of Five. I presented a face of attentive listening; privately, I was freaking. This interview was a train wreck.

My first couple years at EW were exhilarating and overwhelming. Covering Oscar parties, Cannes, and Showest when it was still Showest. Writing filmographies on Milos Forman and Mike Nichols, a profile on Richard Farnsworth, an obit on Bob Kane. My first cover story was about The Haunting, the remake starring Liam Neeson and Catherine Zeta-Jones. What I remember most is that it came out the weekend Amy and I got married. The first cover story I actually liked was about X-Men. A long interview with a young unknown named Hugh Jackman inside a Statue of Liberty gift shop set on a subzero day in Montreal remains a career highlight. We were two golly-gee-whiz guys making the most of a big break. This concludes the degree to which Hugh Jackman and I have ever had anything in common.

Most of my early work at EW was edited by two of the greatest journalists I’ve ever known. Mark Harris pushed me to think better. Jess Cagle demanded I write better. One time, Jess sent back a small thing I did for a Fall Movie Preview with the following note: “This thing is so boring that my eyes rolled out the back of my head, down my back, and got lost with the loose change in my chair. Okay, it’s not that bad, but can you try again? Thx.” I printed this note out and tacked it above my computer where it inspired me for years.

If I improved, it was because of the example and push of the extraordinary writers on staff. Critics like Ken Tucker, Lisa Schwarzbaum, Owen Gleiberman, Gillian Flynn. Feature writers like Nashawaty, David Hochman, Chris Willman, Karen Valby, and the great Benjamin Svetkey. But first and foremost, there was Dan. Our offices were next to each other in the early days. We were always in each other’s offices, assessing and vetting prose, structure, jokes, and everything else. Tenacious D. Van Halen. My wild ideas for comic books. A game we used to play called “Tell me everything you know about [BLANK] in five minutes GO!” Those were the days. Now, we work too much. All of us.

The thrill of talking to artists about how they do what they do was sometimes mitigated by the requirement of inquiring about… other things. No assignment made me more anxious than interviewing Nicole Kidman about Moulin Rouge!, because it meant asking her about tabloid rumors concerning her recent divorce from Tom Cruise. I crapped liquid for a week leading up that conversation and hated myself for a while after it. A close second was interviewing Tom Cruise a couple months later about Vanilla Sky, for the same reason. More liquid crappage, more self-loathing. Nothing about this job really spooked me after that, except the time I interviewed Al Pacino and Meryl Streep, together, for HBO’s adaptation of Angels in America. Their combined suffer-no-fools intensity was so annihilating, actual angels had to be sent to glue me back together.

The first half of my EW tenure was spent mostly covering the new century Geek Pop revolution, and with it, Hollywood’s increasing embrace of franchise filmmaking. It was a nostalgia thrill for me: As I wrote in this personal essay, my sometimes criminal zeal for comic books pretty much made me who I am today. I saw Superman fly over The Daily Planet on a soundstage in Sydney, Spider-Man swing by a web through a studio in Los Angeles, Captain America jump onto a train outside London, Bruce Wayne limp through a Batcave in Studio City, and Hulk smash through Universal City… except the Hulk wasn’t really there, it was just a Hulk head on a stick carried around by a special effects guy. A memory to mirror Hugh Jackman: Sitting with Robert Downey Jr. in his trailer while filming Iron Man, a movie that sealed his comeback and transformed his career. “I remember running into Keanu after he got back from The Matrix, and he said, ‘Brother, it feels like I’ve been on another planet,'” Downey told me while smoking a cigar. “Well, I feel like I’m on Planet Iron Man. And it’s the greatest.” As pop culture evolved to become Planet Comic-Con, EW began going to Comic-Con in San Diego every summer, led by Lisa Simpson, Sean Smith, and an assortment of outstanding editors. Moderating panels became a thing at Geek Mardi Gras; doing the Firefly reunion and the Veronica Mars comeback were highlights. Comic-Con has become an overwhelming zoo. A very sweaty overwhelming zoo. I do not like sweating. But I’ll probably miss it.

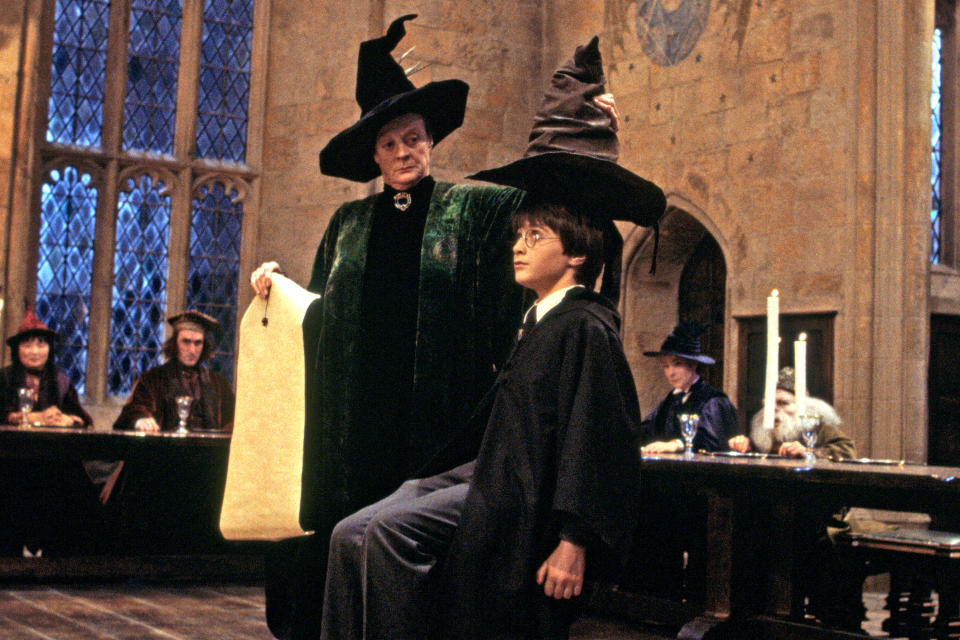

Nothing beat going to Hogwarts. Our coverage of Harry Potter got off to an interesting start. Warner Bros. had a very specific media strategy for launching that brand — and it didn’t include Entertainment Weekly. Silly Warner Bros. We responded by getting Glenn Close-in-Fatal Attraction on them. We would not be ignored. Mark teamed with Dan Fierman — one of the most tenacious journalists I have ever known — to write and report a cover story on the first Potter movie. We scooped everyone else and served our readers well. Fierman did the heavy-lifting; Mark edited the hell out of it and protected us from the corporate wrath that followed.

In the fall of 2004, ABC debuted a high-concept, intensely-serialized, mystery-driven drama from J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof about castaways on a mystical island inhabited by smokey monsters, feral polar bears, and assorted Others. Only three other shows have ever lit me up the way Lost did: Miami Vice, Twin Peaks, and The X-Files. By the time the show premiered, I was well known in the office for emailing staffers my elaborate theories about shared obsessions, most notably Alias. As Lost captured my imagination and ran away with it, I began besieging my colleagues with conjectures about The Island, The Monster, The Numbers, and What it All Meant. In season 2, Henry and Dan Fierman pitched me on the idea of posting these theories on line, using the handle “Doc Jensen.” So it was their fault. The column earned a following. Some people loved it. Some hated it but read it anyway. I’m grateful beyond words for all of those readers.

In the summer of 2006, I pitched the idea of J.J., Damon, and Carlton Cuse sitting down with one of their creative heroes and big-time Lost fan Stephen King for a conversation about how to tell mystery stories on TV. They all agreed. I didn’t need to be there; King served as moderator and did an ace job of it. But hell yes I was going to Maine to be a fly on the wall for that! Afterward, we all went to dinner and a movie, The Descent. After King left us, we all stood in the parking lot, in the rain, a bit dazed. Did we just go on a date with Stephen King? We did.

The Lost adventure meant so much to me, professionally and personally, in so many ways, but the story that means to the most to me is this. In January of 2007, I was in my office writing the first paragraph of a cover story about the third season when my phone rang. It was Amy. She was talking but she wasn’t making sense. It just sounded wrong. I called an ambulance for her. By the end of the evening, we knew she had a brain tumor. This was a crisis. This was a fire drill, but with, like, real fire. And that’s when I realized I didn’t just work with some of the best writers, reporters, and thinkers in journalism, but with a Scooby gang of world-savers. When I think about my time at EW, I think about a group of people who carried my family through an inferno and are now permanently knitted into the fabric of my being like mythology; they are superheroes, none more super than Dan Snierson. That Lost cover story — which he took on and finished, with editing by Dalton Ross and Kristen Baldwin — represents perhaps the smallest of his gestures in the grand scheme of things, but because there’s a physical expression of it, in the form of a magazine with our shared byline on the cover, it’s a symbol of his support and the support of everyone at EW at that time. It’s the first thing that pops into my head when I think about all the things I did here.

I became even more obsessed with Lost as I took on the recap duties in the middle of season 3. Edited and built by an array of editors who were surely traumatized by the experience, those recaps got increasingly longer and goofier and denser and heavier as they became an escape from what was going on at home, for better and worse. They took my mind off my fear and uncertainty, while at the same time nudging me to confront my disorientation and despair. After all, it was a show about being lost. But the recaps are difficult for me to read now because their search for meaning was my search for meaning, their beyond-my-grasp ambition was my need for significance amid a season of life in which I felt very small, their messiness, my messiness. They show me how I use and abuse pop culture to numb and run away, they show me how I make work a self-serving idol. I question how well they served you all. They represented an attempt to “solve Lost,” thus encouraging the impression that Lost was a puzzle to be solved, which is not the best way to engage the show, or any show. It’s a fun way. I can defend it! But it’s not the best. If the recaps enriched your experience, I’m glad. If they exacerbated your confusion, I’m truly sorry. That wasn’t fair to you or Lost.

In my last four years at EW, I’ve had the honor of being the TV critic, writing for several editors, most recently, the very patient Amy Wilkinson. In that time, I also wrote features about Christopher Nolan movies for Sean and various TV shows for Meeta Agrawal, Bill Keith, and more, but nothing has been more growing and challenging than trying to engage TV with a more critical mind. It’s been a struggle for me — a guy who only ever wanted to work in print — to evolve into a digital-era journalist. So I appreciate the grace of all our website editors over the years, especially Christopher Rosen. I have been terrible at telling every photo editor, designer, and copy editor how much their work has meant to me, even as I made their work harder with late copy and changes. Forgive me. The late, great researcher extraordinaire Jenny Boeth, dearly missed here, made everything better and worth the page and your attention. So did Josh Rich and Jeff Labrecque, now a fantastic editor here. I worked on a couple different podcasts with Darren Franich, a great guy with a huge, geeky brain, dynamite way with words, and generous spirit. And a beard. Our conversations remind me of why I love pop culture, why I think it’s important to take it seriously but also to have fun with it, and why I wanted to work for Entertainment Weekly. Thank you, Henry Goldblatt, for every opportunity you’ve given me here, your leadership, and your massive heart. I will never love Shondaland shows the way you love Shondaland shows, but I do love you.

In my first year at EW, I interviewed David Lynch on three separate occasions for three different pieces, including an oral history of Twin Peaks that we did for the magazine’s 10th anniversary issue. I visited him at his home in the Hollywood Hills, and the walk up the winding path to his painting studio in his backyard is seared into my memory. That movement represents everything I ever wanted from this job: The chance to talk to great artists in their space about the stories that fill our culture and move us and shape us, that tell us who we are and help make us who we are. It was full-circle fitting to go out covering Twin Peaks: The Return and to engage a masterpiece with features (edited by Bill), reviews (Amy!), recaps (Kelly Connolly!), and very, very long podcasts recorded with Darren and produced by Cristina Everett. To borrow from Agent Cooper, The Return was a journey that led us to “a place both wonderful and strange,” which is exactly how I would sum up my time at EW, too. I leave here to chase some new dreams in different fields away from journalism — the movie theater/bookstore/coffee shop thing is on hold; still figuring our lattes — but I doubt I’ll ever have a better job than the one I had at EW. Thanks for letting me reflect on it. I hope to engage you in other places both wonderful and strange in the years to come.