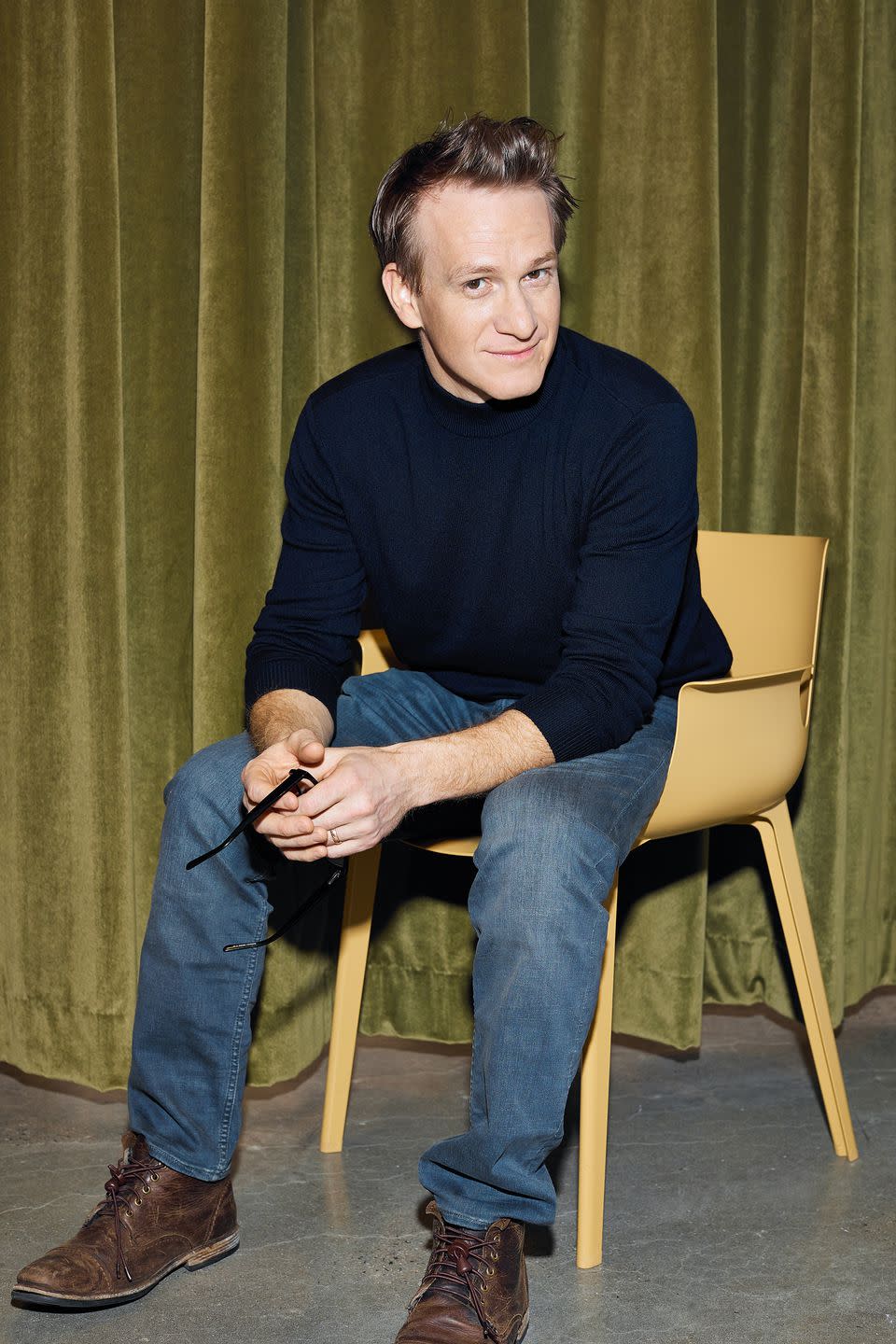

Jamie Parker Is Not Your Typical Harry Potter

Jamie Parker, the actor who plays Harry Potter, is shaking his fist at me. I’ve just told him how cynical I was about Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, a two-part, five-hour sequel to J.K. Rowling’s books that opened on Broadway Sunday night. What was this play, I asked, beyond a cash grab-a performance that will earn millions for its producers and run until the end of time? In an age of remakes, this is Harry Potter’s reboot.

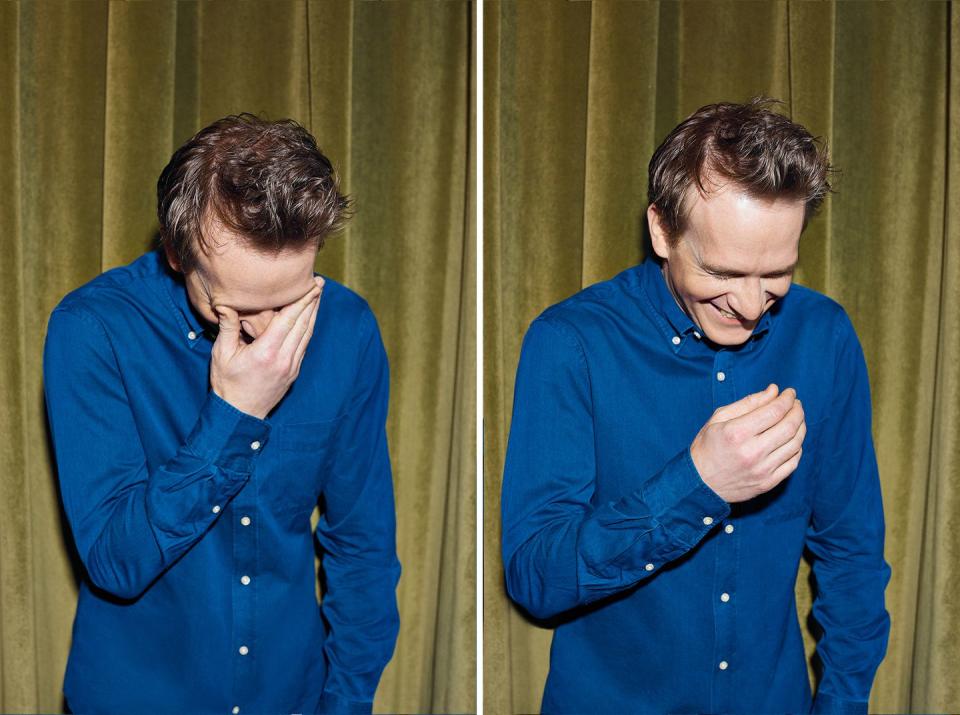

What I also tell Parker is that by the end of the play’s fourth act, after taking in more than five hours of the show’s dazzling wizardry, I was crying. Not a single tear-more like a waterfall. In a show packed with stage illusions and trickery, I was moved, unexpectedly, by the intense theatrical experience.

Parker, who is reprising his award-winning performance in the original London production of Cursed Child, laughs at me and shakes his fist as he mimics my fake-outrage at being brought to tears by his play: “Damn you!” He’s heard this before, and he’ll likely hear it again.

“You’d be forgiven for being intensely cynical going into this play,” Parker tells me, as he knows exactly what the show looks like from the outside. “But I defy you to be cynical when you come out.”

It’s safe to say most people are quite affected by the show. While Cursed Child’s success should come as no surprise-it is part of a hugely popular book and film franchise, after all-the critical response is equally glowing. The London production earned eleven Olivier Awards (the U.K. equivalent to the Tony) and took home nine of them. Parker earned his first Olivier for Best Actor, as did two of his cast mates. The Broadway production will no doubt be a smash on this side of the Atlantic, too-and it could very well earn Parker a Tony. Harry Potter and the Cursed Child might change Broadway forever; Jamie Parker, too, might change what audiences think of Harry Potter.

“What house are you in?” Parker asks me.

I should have expected this question. Among fans of the Harry Potter series, it’s essential conversational currency. Harry and his friends, Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, were famously sorted into Gryffindor; their teenage foes, Draco Malfoy and his henchmen, were Slytherin. There are also Ravenclaw and Hufflepuff. In the books, the dormitories determine their class schedules, their friend groups, and general life trajectory. For Harry Potter fans-Potterheads-the houses represent four distinct personality types.

When Parker asks me the question, I’m slightly embarrassed to admit that I don’t have an answer. I wouldn’t identify as a Potterhead by any means. I read, and very much enjoyed, the books when they were first published in the States. (The same goes for the films, the first of which premiered my freshman year of college.)

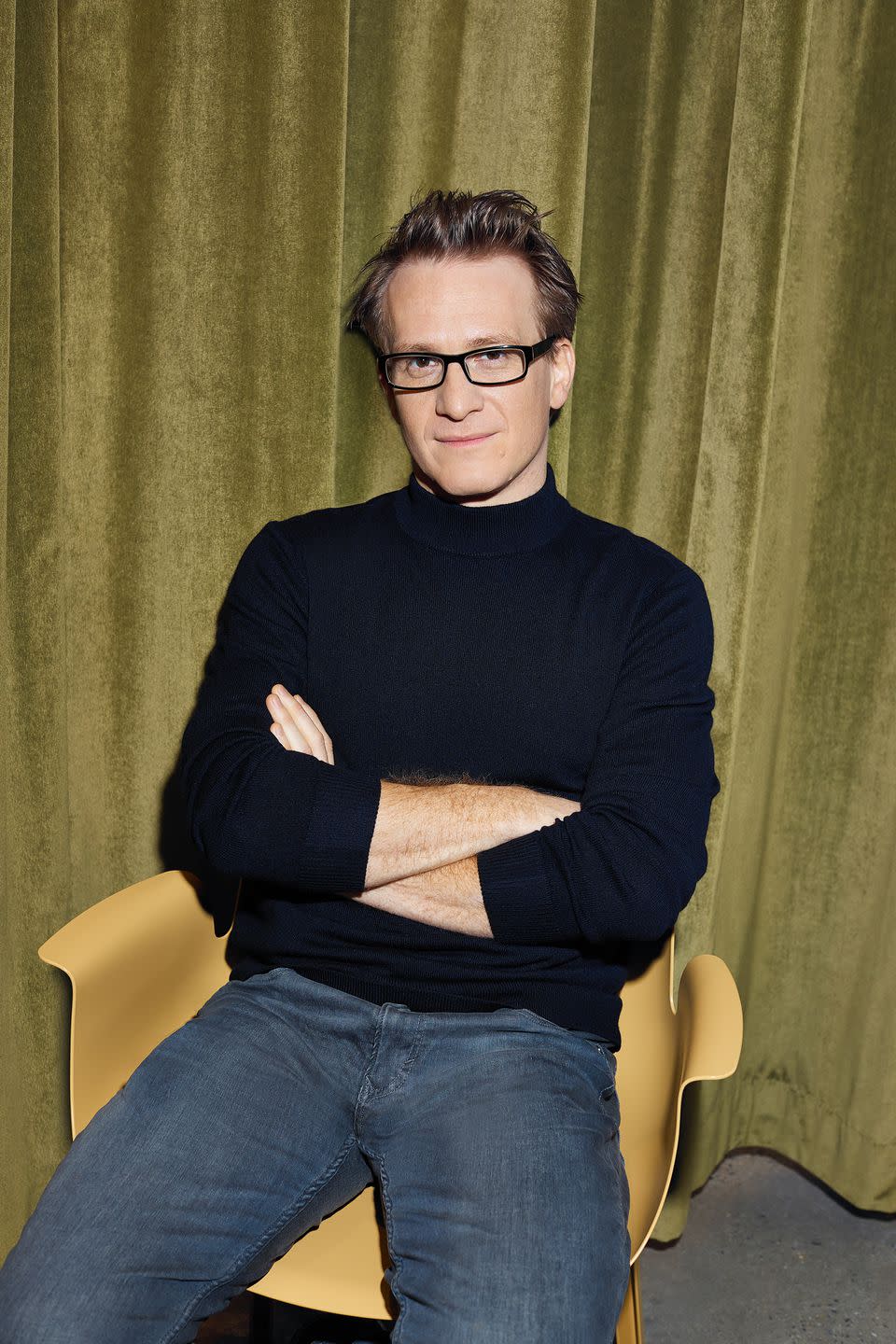

Parker was in a similar position before he landed the role in the original West End production of Cursed Child, which opened in London in summer 2016. “I was definitely a part of that generation,” he tells me. Parker is roughly the same age as Harry Potter. (Parker was born in 1979; in the Potter timeline, Harry was born in 1980.) “I was twelve when I went to boarding school in Edinburgh,” he says. “I had my little round glasses, I used to hang around all of the places where Jo [Rowling] was writing the books. But I was a bit older when [the mania] was properly kicking off, and I slightly missed it.”

Parker implores me to find out my Hogwarts house, instructing me to log onto Pottermore.com to take the quiz and have the digital Sorting Hat choose my fate. So I answer a few questions about my deepest fears, the animal I’d take with me to the magical boarding school, and there it is: Slytherin. I’m not particularly surprised (I mean, I’m the guy who has just admitted his cynicism about the Harry Potter play). But Parker, who’s a Gryffindor just like his on-stage counterpart (“Of course!” he laughs), exhibits a moment of apprehension.

“A Slytherin journalist!” he says, “just like Rita Skeeter, with her Quick-Quotes quill. I’ll have to be careful with this one.” (Parker is referencing the gossip-slinging writer for the Daily Prophet-London’s newspaper for wizards in the Potter series-who crafts sensational tabloid stories about Harry.)

I can see why Parker is a little nervous to talk about Cursed Child. In fact, there’s so much about the show that I can’t talk about. The whole production is shrouded in secrecy, which is surprising. The play has run for almost two years nin London and millions of fans bought a copy of the script when it was published the day after the West End premiere.

Here’s what I can say about the play’s plot: It takes place nineteen years after the events of the final book in the original series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Harry and Ginny Weasley are married with three children, and their middle son Albus is about to begin his first year at Hogwarts. His cousin Rose (daughter of Hermione and Ron) is also a first-year, and so is Scorpius Malfoy-the son of Harry’s nemesis, Draco. Albus and Scorpius become unlikely friends, and just like Harry, Ron, and Hermione, they set out on an adventure that puts them in danger and creates plenty of conflicts for the adults who want to keep them safe at any cost.

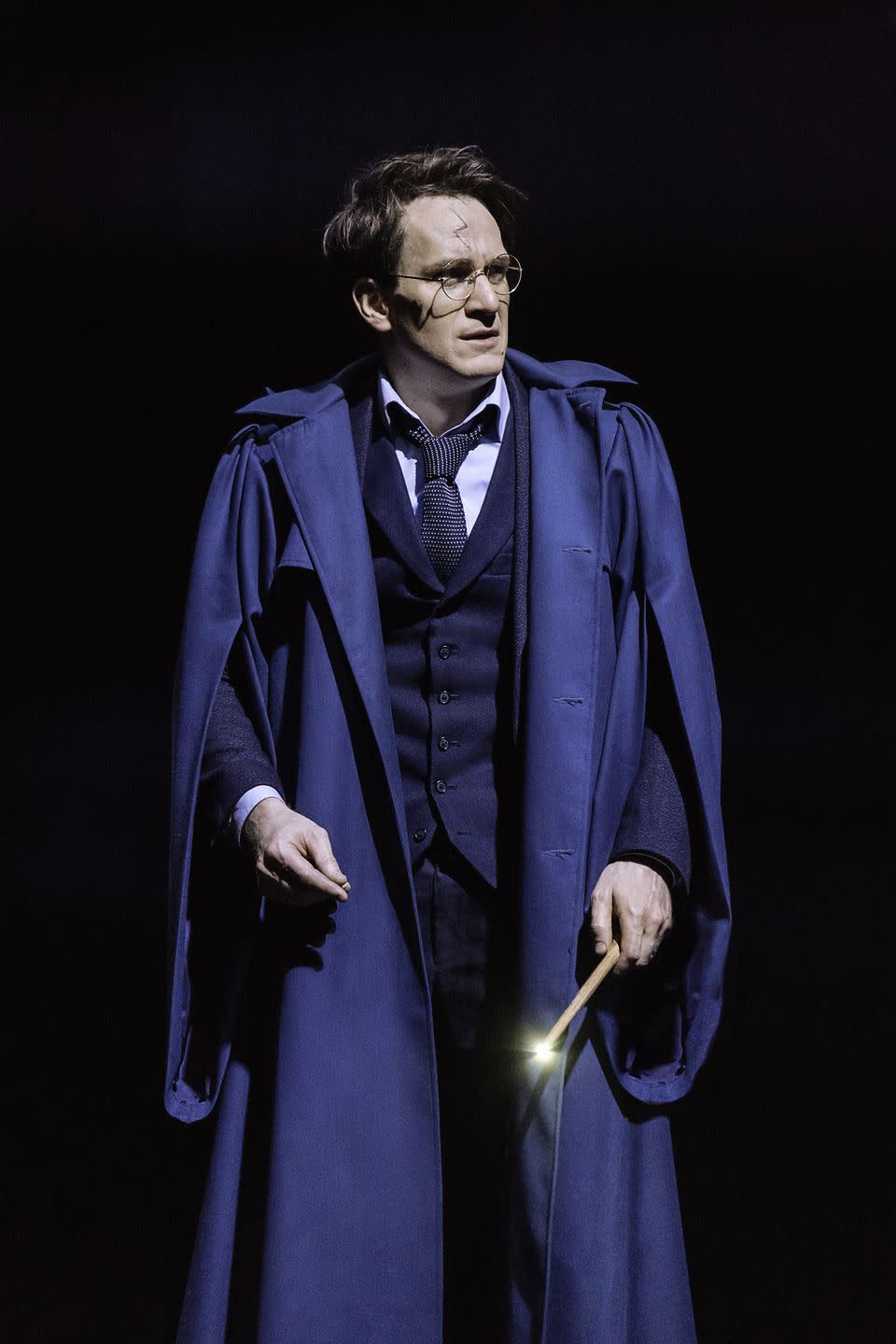

While the young duo may drive the plot of Cursed Child, the original trio of Harry, Hermione, and Ron-plus Ginny and Draco-get in on plenty of the action, even though they’re approaching middle age and are dealing with the emotional weight of being parents. That’s the thematic core of the play, and what Parker’s Harry Potter drives home: the complexities of parenthood, the conflict that occurs when you want to allow your child to become his own person, to learn from his mistakes, but also to keep him from making the mistakes that could alter his life irrevocably.

That emotional thrust of the play is what appealed to Parker, a seasoned actor who has plays by William Shakespeare and musicals by Steven Sondheim on his resume. He had read an early draft of Cursed Child after it had already begun development. “I signed an NDA and sat in somebody’s office for a few hours, reading 250 pages in a sitting,” he says of his first encounter with the script. He hadn’t yet done his Harry Potter research, having not read (or seen) the events in the later books and films. He didn’t even know which role he was being considered-and he was a bit dubious about the concept altogether.

But then he read the script, and made it to the final moments in the play’s fourth act. (The entire play is so long-over five hours in full-that it is presented in two parts à la a weighty Shakespearian history.) It’s then that Cursed Child meets an emotional crescendo, when the play becomes less like a highly profitable tie-in to a massively popular franchise and more of a staggering piece of theater. For an actor like Parker, that was the draw. “I was circumspect going in,” he admits, “but it was clear the producers were aiming to make the best possible piece of theater they could. They weren’t just doing one of the books in a place where they could charge tickets for it.”

There is plenty of magic in Cursed Child, and that’s exactly why this five-hour play is worth seeing: Even the most casual Potterhead-or the average theatergoer-will be stunned to see the wizardry that J.K. Rowling created on the page take place before their eyes.

Despite the show’s dazzle, the script shines through. Playwright Jack Thorne wrote it, based on a story he developed with Rowling and the play’s director, John Tiffany. Many Potter fans who eagerly got their hands on the script before seeing the play have bristled at the idea of this outsider’s perspective on Rowling’s world. Some even called the story little more than fan-fiction. It’s an understandable criticism. These beloved characters are, after all, nearly two decades older than when we last saw them. Their lives have unfolded off the page. Any time-jump creates a jarring affect: This is not the Harry Potter that many people know and love.

There’s the other obvious change: Before Parker, of course, only one actor had played Harry Potter-a role more strictly defined by the person who played him than, say, anyone in a Tennessee Williams play. Sure, Parker once played Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, but Paul Newman’s portrayal isn’t the definitive version of that character. Daniel Radcliff, on the other hand, became famous because he was Harry Potter.

Parker doesn’t see Harry Potter as simply a movie character. “It would be incomplete to take the movies as the source material, because they're not,” he says. “I don't think it's necessarily about being a different version of Harry from Daniel's Harry, or anybody else's Harry. I think both of us were trying to draw a straight from the books to whatever we were interpreting.”

But Jamie Parker’s Harry Potter isn’t too far removed from the character in the books or the movies. He still carries the traumas he experienced throughout his childhood, which he now tries to avoid projecting onto his son. He must reexamine and reckon with those experiences from a new point of view, which is why a new actor-and a fresh perspective-is so vital to this version of the character. and bring the perspective of an actor new to the character.

When Parker speaks of Harry Potter as a character, he avoids the mythical elements that many other characters in Rowling’s world see him as. He’s more than a famous wizard who lost his parents to Voldemort and then defeated the Dark Lord as a teenager. In the books, he’s still a boy. “He has to learn, and he has to find out what happens when he doesn't file his homework, when he fails or when he gets marked down, justly or unjustly,” Parker says. Like anybody else, Harry continued to learn valuable lessons about being a person as he maneuvered through adulthood-particularly as a father.

Theater is a medium that relies on emotions; not just that, but watching an actor externalize emotions in big ways. It’s with that understanding that Parker approached this role. “You take a child who's been through this trauma through his most formative years,” he says. “What kind of parent does that create?”

Harry’s relationship with Albus is complex and complicated; they are two bold characters who often butt heads-two of the play’s protagonists, really, vying for your attention-and the journey they go on together leaves the audience primed for a catharsis by the curtain call. Parker is a father; his son, William, is seven. And while he’s not a recent dad, this marks the first time he’s playing one on stage after being on the opposite side of father-son dialogue. “I think that is the experience of parenthood, generally,” he laughs. “’But I’m the kid!’ I’m suddenly saying this as a father?”

When I ask him if he got any specific advice from Rowling when it came to tackling the character, Parker doesn’t miss a beat. “She gave me seven volumes of it,” he replies. “I mean, not to be glib, but it’s all there.” He speaks of Rowling as one of the great literary masters, someone who built a grand world that, at its root, is incredibly humane and therefore personal. “It goes back a long way,” Parker says, “that very old, primordial level. Whatever your demons are-or dementors-it’s very personal for everyone. When you bump into people at the stage door, you see they’ve had a visceral, physical reaction to the show. It’s the same for me, I think. There are a lot of personal conversations that have been provoked by the play, and that’s caught people by surprise.”

Rowling also recognized that the theatrical world offered a chance to tell this story in a different, specific way, and she put her full trust in director John Tiffany, the show’s producers, and its cast to tell that story. “She didn’t pretend to be a playwright or a director or an actor or a sound designer,” Parker says. “It astounds me, the degree to which the tight control that could have happened on this has been willfully relinquished just in the name of letting people do their jobs.”

The true collaborative effort has proven to be a success; Cursed Child, unlike any theatrical event I’ve ever seen, is primed to have a long and healthy run on Broadway. It’s a true game changer for a play, as the longest-running productions-shows like The Phantom of the Opera, Chicago, Wicked, potentially even Hamilton-are all musicals. But despite this being a commercial no-brainer, something that will make more money than any of the goblins in the Gringotts Wizarding Bank could possibly imagine, Cursed Child also has the heart of any other well-crafted, evocative play.

“There's a reason that mythic template is told over and over and over again,” Parker says. “We go through that so many times over the course of our lives, and we need to keep telling that story. That's why I think we've got seven-year-olds in the audience sitting next to the 35-year-olds, sitting next to 70-year-olds. It’s never irrelevant.”

By bringing the world of Harry Potter into this new medium, expanding beyond the page and film and into a space somewhere in between, the creative team has cemented its timelessness even firmer. And the themes of the play-of evolution, and change-are so easily extended to justify Harry Potter and the Cursed Child’s existence. “It can be painful leaving parts of yourself behind,” Parker says, “Change and shuffling off your previous skin is traumatic, but it can be done.”

Photography by Kat Wirsing • Grooming by Ellen Guhin at See Management

You Might Also Like