“Like James Jamerson, Tommy Cogbill was a take-charge guy in the studio”: Inside the recording of Son of a Preacher Man

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“There are plenty of correlations between James Jamerson and Tommy Cogbill,” said Nashville session bassist Michael Rhodes, who was interviewed for the February 2006 issue of Bass Player. “Like James, Tommy was a take-charge guy in the studio; he would stand up and count off the songs, and basically run the session. He had such a strong presence in the music he played that there was a sort of natural deference by the rest of the band. There’s probably no better example of that than Son of a Preacher Man.”

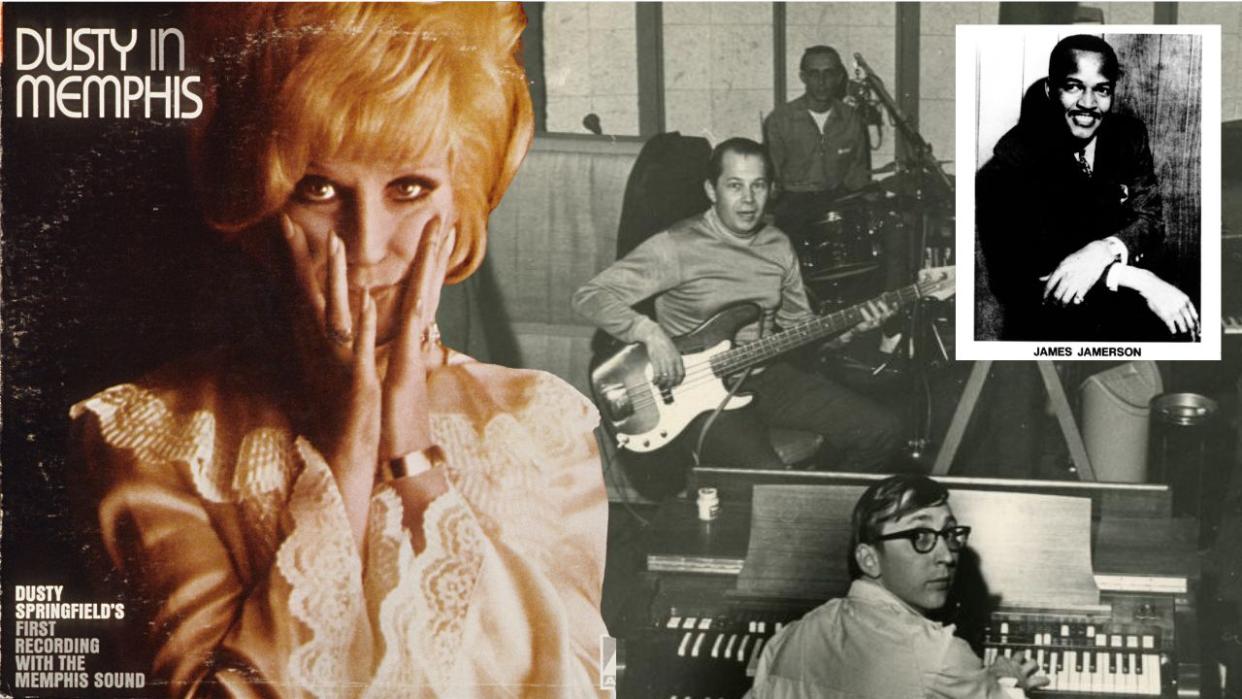

The 1969 Top Ten hit came from British pop/soul singer Dusty Springfield’s album Dusty in Memphis. It’s considered her masterpiece, although it was her last major hit. Rhodes, who sadly died back in March 2023, had gathered some background info on the late-1968 date at American Sound.

“There weren’t a lot of takes done, because the producer (Jerry Wexler), the engineer (Tom Dowd), and the songwriter (John Hurley) were all present, so there was a better degree of direction," said Rhodes. “The rhythm section recorded live to a scratch vocal by Dusty, who – being somewhat out of her element – was reportedly as nervous as a cat in a room full of rocking chairs.”

The two-and-half-minute hit song begins with interplay between Reggie Young’s guitar lick on the downbeat and Cogbill’s instantly funky response in the back half of each bar. “What strikes me is how sparse and laid back the first verse is, except for Tommy,” said Rhodes. “He takes up the bulk of real estate and gives the song a sense of urgency and excitement. You can hear drummer Gene Chrisman and everyone else starting to follow him because he’s really in the zone, right in the middle of the pocket.”

As the track moves to the first chorus, Cogbill continues his syncopated bassline. At times he adds the dominant 7 (D) to the E triad chord change, as well as some expressive hammer-ons and slurs. “The fact that Tommy is playing around the E up at the 7th fret tells me these guys had heard themselves on the radio and knew what translated,” said Rhodes. “If he had played open E it might not have reproduced as well in a car or on a transistor radio. And given that Tommy also played bebop-style guitar, navigating around the upper frets was no sweat.”

Following a re-intro (in which the horns enter and cop Young’s guitar lick), Cogbill continues his percolating bass part – adding subtle variations – through the second verse and chorus. As the bridge begins, in what is a clever setup for a modulation to the key of A, Cogbill keeps driving forward, issuing an ear-catching 5th on the downbeat, followed by a jazzy passing tone.

The third chorus establishes the new key of A, with Cogbill maintaining forward motion. Every time he arrives at the IV chord (D), he outlines a D triad (D-F#-A). He then plays an inspired, bluesy fill as a precursor to the final chorus.

“Tommy felt the final chorus needed to go into another gear,” said Rhodes. “His playing was always headed toward something – the next chord change or the next section, and he knew he had to get right to it before the quick fade. Moving up to a more vocal, conversational register, he plays a linear fill across the bar line without worrying about nailing the roots.”

Gear-wise, Tommy used a 1959 P-Bass, which had a rosewood neck and flatwound strings. “It was the American Studios bass guitar,” said Rhodes. “Mike Leech said that Tommy also kept a jar of Vaseline on hand, and he would stick his right fingers into it to help facilitate his technique.”

Guitarist Reggie Young remembers there being a bass amp at the session, and with Dowd present there was probably a direct as well as a miked amp signal. “Interestingly enough, Mike Leech had said that on the earlier sessions, Tommy’s bass was recorded through an old Fender Twin Reverb that had one of its two 12-inch speakers busted,” said Rhodes. “They would place a mic, probably a Shure SM57, off axis of the single speaker and keep the amp at a low volume.”

Born on April 8, 1932, in Johnson Grove, Tennessee, Cogbill’s trademark busy-yet-unimposing basslines also graced Wilson Pickett’s Funky Broadway, Elvis Presley’s Kentucky Rain and In the Ghetto, the Box Tops’ Cry Like a Baby, and Aretha Franklin’s (You Make Me Feel Like a) Natural Woman and Chain of Fools.

“Tommy's profile has always been subdued – as he wanted it to be,” the late Mike Leech once told BP. “However, from a historical perspective, he should be listed among the top-five most important bassists of the last century.”

Dusty In Memphis is available to buy or stream.