Before the internet, one housewife was there to save your favorite show from cancellation

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was the spring of 1983, and Dorothy Swanson was angry.

Her favorite television show, "Cagney & Lacey," which had premiered a year earlier, was on the verge of cancellation after its first season got poor audience ratings. The married mother of three loved that the procedural centered on two female cops, Christine Cagney and Mary Beth Lacey — fully formed characters who epitomized the struggles of second-wave feminism. "Cagney & Lacey" spoke to her as no television show had before. She had to do something to keep it on the air.

So she wrote a letter imploring CBS to save the show. Then she wrote another, and another.

Swanson didn't know she was walking in the footsteps of the fan-led "Star Trek" letter-writing campaign that had rescued that show from doom nearly two decades earlier, in 1966. "It just sort of fell into my lap," Swanson told me when I reached her over the phone.

But after mailing hundreds of letters — some sneakily signed with other names to create the illusion of a bigger campaign — she had accomplished something incredible. Thanks to Swanson's tenacity, vociferous critics who supported the show, and savvy producers who embraced both, CBS gave "Cagney & Lacey" a second chance. It would run for five more critically acclaimed seasons. Executives credited the outpouring of support from viewers and the letters they'd received as reasons for the reversal of fortune.

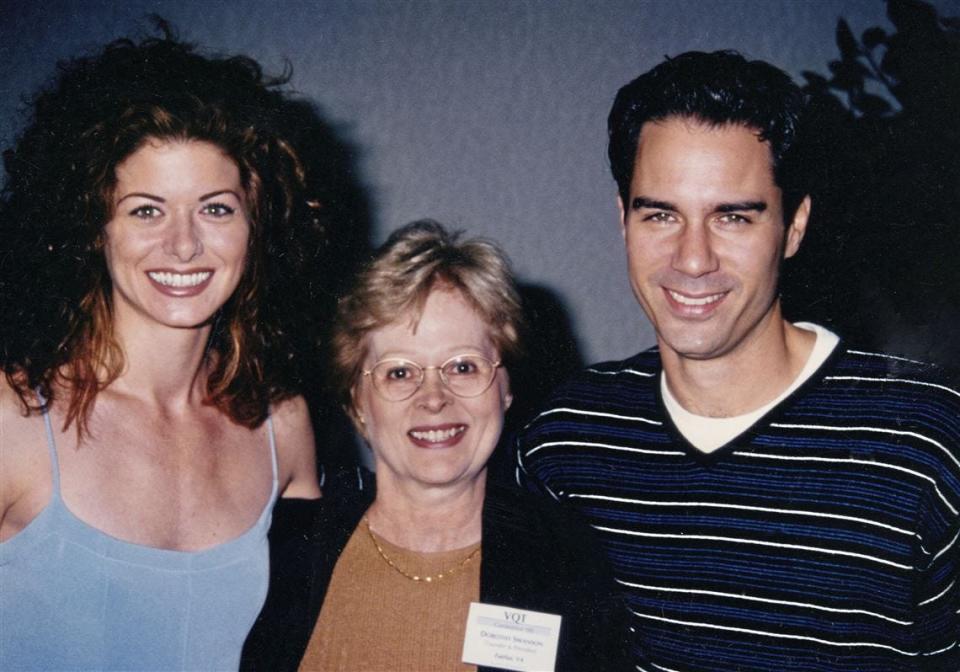

In time, Swanson would parlay that success into a role as a Hollywood tastemaker, rubbing elbows with sitcom stars and network execs. And she'd do it by harnessing the power and enthusiasm of fans.

A grassroots campaign rooted in passion

"Dorothy Swanson undoubtedly started her first campaign because she was a big-time fan," said Michael Sparaga, the director of the 2018 documentary "United We Fan," which chronicled Swanson's story. "Nobody types up 500-plus letters, forges signatures of friends and family, and mails them to CBS while also rallying thousands of other viewers through the media to do the same if they're not absolutely obsessed with a show."

Swanson connected with Donna Deen, a fellow TV fan in Plano, Texas, who'd embarked on a similar letter-writing campaign to save the prestige-y hospital drama "St. Elsewhere." In 1984, the two formed Viewers for Quality Television, an advocacy group aimed at protecting high-value TV shows from cancellation.

Swanson said in an interview from her home in Florida that while VQT "must be looked back on as rather quaint," writing letters "was, in its time, the thing to do."

People who learned about VQT from critics' columns in newspapers and magazines could write to Swanson and pay a fee to become a member. Then they'd receive VQT's monthly newsletter and be able to vote on which shows VQT would endorse as "quality" — and thereby pledge to stand by if they were threatened.

It was a simple strategy focused on democracy. And for more than 15 years, until 2000, it worked. In addition to "Cagney & Lacey," the group strongly advocated smart hourlong dramas, including "Quantum Leap" and "China Beach." In doing so, it portended the type of fan advocacy that would become even more rampant with the advent of the internet.

Ready for prime time

VQT had discerning taste and supported well-remembered critical favorites like "Homicide: Life on the Street" and "ER."

The group also supported the controversial '90s cop show "NYPD: Blue," which featured unprecedented-at-the-time swearing and nudity, after advertisers began to pull out. In a 1994 interview with The New York Times, Swanson described it as "really a very moral show." It went on to win the Emmy for best drama series in 1995.

But plenty of other VQT-supported shows, like "Frank's Place" and "Picket Fences," quietly disappeared into the mists of time.

Where today's fandoms are typically focused on a single show, VQT "became a community of television watchers who liked the same type of shows," Swanson said. At its peak, it had more than 5,000 members.

The group was also singular enough in the '80s to garner attention from network executives and celebrities. Each year the group hosted a VQT convention in Los Angeles featuring panels with executives, writers, and actors, as well as an awards banquet where stars like Jerry Seinfeld, Ron Perlman, and Julia Louis-Dreyfus would show up to accept their Q Awards.

VQT became a part of the industry, representing viewers from a vaunted position that Swanson refers to as a "seat at the table." As an added bonus, stars would hug her when they saw her, invite her to their sets to watch VQT-approved shows during filming, and sometimes even call her up just to say hello.

Swanson considered VQT as "sort of partners" with "the television journalists and the viewers," she said. Critics across the country had Swanson's phone number, and she had the numbers of showrunners, TV executives, and publicists, including heavy hitters like Les Moonves and Dick Wolf. VQT "took a stand on behalf of television, not against it," Swanson said in her 2000 book, "The Story of Viewers for Quality Television: From Grassroots to Prime Time."

For better or worse, that symbiotic relationship between audience and industry doesn't exist today — now, as numerous streaming and social-media platforms aim to cater to each viewer's specific taste, the TV industry is increasingly personalized and fractured. (Just ask me about the time I protested outside Netflix's headquarters in 2021 to bring back "The OA" — there were only about 20 of us, and nobody treated our presence as anything more than a curiosity now.)

And anyway, that relationship would eventually end up burning Swanson.

Upholding the professional objectivity that lent VQT its legitimacy sometimes cost her friends and connections. Deen, Swanson's cofounder, dropped out after a few years over a disagreement about campaigning for the sitcom "Designing Women." And Barney Rosenzweig, the "Cagney & Lacey" executive producer, never forgave Swanson's group for printing critiques of his follow-up show, "The Trials of Rosie O'Neill," after helping launch Swanson and VQT to prominence.

A fan empire in decline

At 84, Swanson doesn't watch much TV anymore because of vision loss, but she looks back fondly on VQT's impact on the industry during its active years: the shows it saved and the stars it supported. She said that by the time she decided to close down VQT in 2000 amid declining membership, "we had accomplished what we set out to do, which was educate viewers in how to make a difference by themselves."

Twenty-three years later, the TV landscape is nearly unrecognizable — as is the way fans campaign to keep their shows on the air.

It's difficult for fans to speak as one voice loudly enough to attract attention when shows' audiences are small and divided. Plus, it's easy for networks and platforms to kick shows to the curb for any reason at all, especially when they aren't obligated to disclose viewership numbers.

It's a far cry from Swanson's direct line to CBS's C-suite.

Because Viewers for Quality Television was a product of its analog environment, it's hard to imagine an organization like it existing today.

"They were discerning, disciplined, passionate, and I miss them," said Matt Roush, a senior critic at TV Guide whom Swanson fondly recalled as one of VQT's most loyal supporters.

But there are plenty of lessons today's fans can learn from VQT about the importance of building community, the difficulties of remaining objective, and the fickleness of the industry.

VQT's "idea of 'We're your core audience, we are valuable' has never gone away," said Mel Stanfill, a professor at the University of Central Florida who studies fan labor, including fan campaigning.

Sparaga said what he found most interesting about VQT "was that not every member loved every show VQT supported, but they all loved belonging to an organization that was dedicated to supporting higher quality TV in general." There was a broad feeling of loyalty and obligation among members: They "would write letters to try and save TV shows they might not even be watching," Sparaga said, "because then other members would write letters to support the shows they were watching."

It's a simple but game-changing idea: Everyday viewers deserved programming that challenged them, enthralled them, and changed their minds even as it entertained them.

For her part, Swanson was glad for an opportunity to reflect on her days as doyenne of VQT. "If you're going to take a path less walked, then leave your footprint," she told me. "I guess we left our footprint."

Read more on the past, present, and future of fandom:

The streaming apocalypse is nigh. Some are preparing their storm shelters now.

Netflix canceled their favorite show. They mounted a global campaign to save it.

Read the original article on Insider