Inside the world of typewriters and the niche hold they have on the modern world

It was a pandemic distraction from lockdowns and languishing. I had somehow convinced myself I needed a typewriter. Locating one was easy, but I wasn't expecting to find Cincinnati eclectic Richard Polt, a man dedicated to chiseling out a space in the modern world for these old, sturdy writing machines.

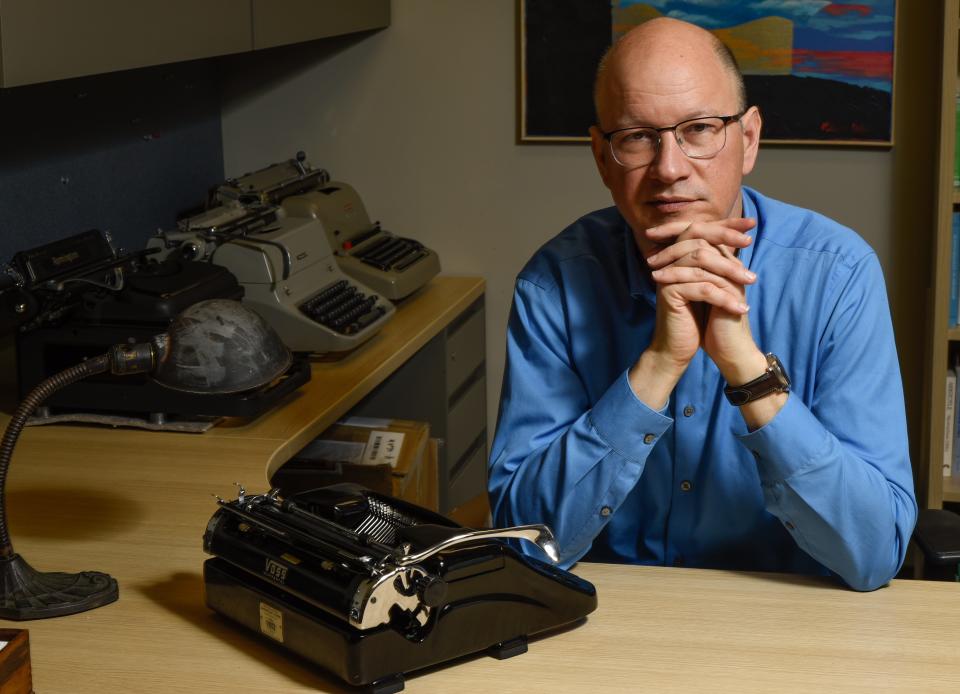

Polt is an avid collector, a godfather among a growing group of enthusiasts and the author of "The Typewriter Revolution," which contains his call to arms, "The Typewriter Manifesto." He was even in a film with Tom Hanks.

Ironically, I found him on Facebook – though I didn't know it was him. In the summer of 2021, I came across the page "Urban Legend Typewriters" selling refurbished machines. Proceeds from the sales go to WordPlay, a local nonprofit writing workshop for kids. I arranged to meet the proprietor a few days later.

I found myself on the front porch of a three-story home, well-shaded by tall trees in the yard, in Spring Grove Village. I was expecting a mid-20s hipster, perhaps with a tattoo of a typewriter on his forearm. Instead, I was met by more of an any-dad with glasses and a shaved head. He brought two typewriters, heavy in their well-worn cases, onto his front porch.

I picked up a Royal Quiet De Luxe typewriter, which I later learned was the preferred weapon of Ernest Hemingway and Ian Fleming, then he offered me a copy of his book.

Book? I thought. And then it clicked, While spiraling down all the internet rabbit holes leading to my purchase, I had come across Polt and his book, but in that moment I was shocked to find myself standing in front of the man. After our brief encounter, I read the tome and I had to know more.

How he got here, what he thinks of today's technology, why he holds dear this past-century machine and how one makes the jump from simply collecting to proselytizing to the masses.

How do you interview someone like Richard Polt? I figured the best approach would be an old-fashioned one: Correspondence by typewritten letter.

The manifesto

For nearly a century, a typewriter was a machine of power, of war.

There's an old Underwood typewriter manual that included instructions for "demolition to prevent enemy use."

"Smash typewriters and components with a sledge or other heavy instrument; burn with kerosene, gasoline, fuel oil, flame thrower, or incendiary bomb; detonate with firearms, grenades, TNT, or other explosives."

Typewriters were dangerous. Polt argues they still are or at least they can be.

"We assert the right to resist the Paradigm, to rebel against the Information Regime, to escape the Data Stream," Polt wrote in the Typewriter Manifesto printed in black and red at the front of his book.

Polt's book casts typewriters as a tool to fight eroding privacy and the overwhelming, all-consuming connectivity of social media. Typewriters offer an analog experience craved by so many, the same folks drawn to records, film cameras and fountain pens.

By documenting those who use typewriters – teachers, poets, artists, students – he shows the value people find in the machines. The way the words feel more concrete. The lack of distraction that comes with being unconnected to the depths of the internet. The physical creation of ink and paper.

"We choose the real over representation, the physical over the digital, the durable over the unsustainable, the self-sufficient over the efficient," Polt wrote in the manifesto.

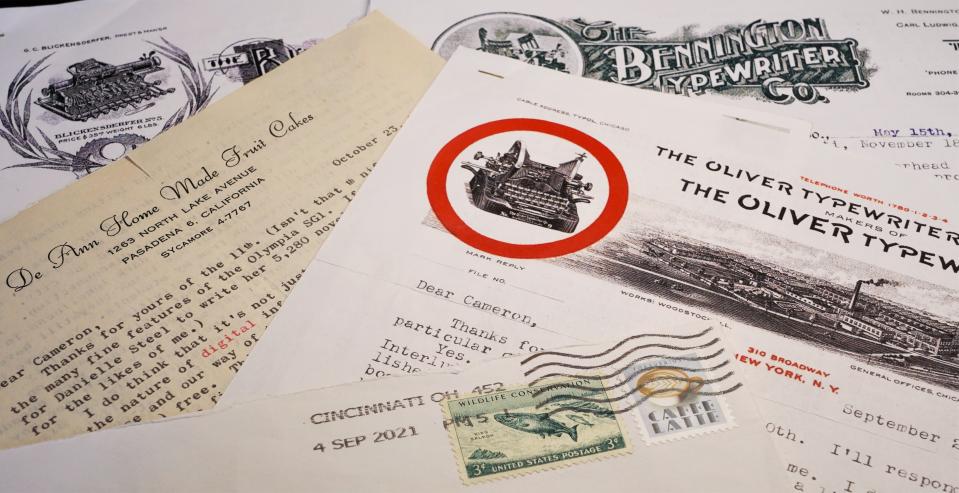

Polt's response to my letter came about a week after I sent mine.

It came in an unassuming white envelope. Where the return address would normally be printed was instead a stamped image of a typewriter. On the opposite corner of the envelope was a modern stamp and a 3-cent stamp featuring a detailed engraving of a king salmon printed in green. In yet another research adventure, I learned the stamp was printed in 1956, part of a wildlife conservation series.

Inside, I found a letter typed on, of course, typewriter letterhead.

I had asked him about one of the main themes of his book: that slow, analog communication can serve as an antidote in a world saturated with social media, censorship and misinformation. We were fresh off the 2020 election and mid-pandemic. Meme bots and wild claims were everywhere online.

"I didn't know that social media has changed so much since 2015, since (ironically) I developed my social media accounts only to promote my book that attacks the omnipresence of digital technology," he typed. "I try to keep clear of the political poison that makes the round of social media and the internet more generally."

For Polt, at least, it seemed the medicine was working.

Key correspondence about machines and a lost art

Polt and I corresponded for several months. We talked about privacy, technology and, of course, typewriters and letter writing, many of the topics he touches on in his book.

He was born in Madrid in 1964, the son of a Spanish literature professor. Growing up, his family split their time between Madrid and Oakland, California, where most of his family still lives.

Several of the letters he wrote were hammered out of the Remington Noiseless No. 7 typewriter he received when he was 12 years old, but his passion for typewriters would not take hold until later.

After college, Polt landed at Xavier University in 1992 to teach philosophy.

He's led a number of different courses exploring everything from the philosophy of communication and memory to the philosopher and holocaust survivor Hannah Arendt. His research focuses on German philosopher Martin Heidegger. He even managed to get a typewriter signed by the man, though Polt believes he never used it because he despised the machines.

In the mid-1990s, Polt really dove into the hobby after finding a defunct newsletter and a book about typewriter collecting. In December 1995, he built "The Classic Typewriter Page" and put it online. The website contains a blog and huge repository of typewriter information and manuals, and it put him in touch with people all over the world.

"I've found that typewriters can interest just about any sort of person, regardless of race, gender, religion, education, wealth, or politics," Polt wrote to me. "The typewriter is a tool for solitude, for dwelling with your own thought. But not just that; it can also be a way of reaching out to others, as typewriter poets do on sidewalks."

Polt said this real-world connection – real letters, meetups called "type-ins" and other public events – is another thing that can make typewriters special.

During the next decade, Polt and other typewriter enthusiasts leveraged the internet to connect. Blogs sprang up, as they did on every topic imaginable, and the "Typosphere" developed its own culture and became a place where people would share typewritten material.

For Polt, philosophy and typewriters came together naturally with the 2015 release of his book. It's a maintenance guide, buyer's guide, mission statement and documentary project all rolled into one. Polt lays out the argument in its pages:

"Online social media promise to provide human connections. And they do – but the connections are filtered, skewed, and spread thin. Beyond a certain level, sharing isn't care," he wrote in the book. "Put a typewriter in front of people and they'll want to write from within. The typewriter doesn't push 'content' at them; it draws words from them."

Information age drawbacks

Polt's third letter came to me on vintage letterhead. "De Ann Home Made Fruit Cakes" was printed at the top of the half-sized sheet in a script font.

We corresponded about the drawbacks of the information age.

"Optimists thought that it would lead to greater enlightenment and cooperation around the world," he wrote. "We now understand that digital mis/dis/information, free of context or evidence, can spread like wildfire and that as we have lost the central set of trusted sources for our culture, we tend to fragment into cliques and cults in which we communicate only with those who already agree with us."

But he admitted abandoning the modern digital world is too extreme. He said he would miss video calls with his son in California and the connections he's made with other enthusiasts. He said he still thinks he has too many digital habits and responsibilities. He tries to approach it all with moderation.

In 2016, he was featured in the documentary "California Typewriter," which gave a look inside an old typewriter repair shop struggling for business and extolled the virtues of mechanical writing. Tom Hanks and John Mayer, both avid typewriter users, appeared in the film as well.

In the movie, Polt showed the letters he received from all over the world in response to his Typewriter Manifesto – communiques from fellow "insurgents," many written in revolutionary style hearkening back to the days of spy craft.

And while social media may, in some ways, be the antithesis of typewriters, it has helped spread the message. YouTube has hundreds of videos about repairing, collecting and using the machines. Prices for used typewriters soared during the pandemic. And many point to Polt and a few other diehards, like Ted Munk and his enormous database of machines, for inspiration.

"I see myself as a participant in and promoter of the typewriter insurgency. I certainly didn't create it, and I'm not its president or leader," Polt wrote, but acknowledged that "The Typewriter Revolution" helped articulate what was already happening and bring it into focus.

"I think there's a good, solid 1% of people who would enjoy and benefit from a typewriter," Polt said, and it's worth trying to reach all those people.

'He's a hero'

Sarah Everett is one of the 1%. She's just a few years out of college in Pennsylvania. She likes to paint her nails to match her typewriters. She also runs a YouTube channel called "Just My Typewriter" where she repairs and sells typewriters, gives tips to newbies and even looks at typewriter merchandise.

"I actually started collecting typewriters because of the documentary 'California Typewriter,' which Polt is featured in," she said. "I was completely fascinated by the machines and the response to the typewriter manifesto Polt released on his blog. He's a hero to the collecting community and an amazing resource of information. His book is a collector's bible."

Joe Van Cleve is another YouTube personality and renaissance man from New Mexico. Unlike Sarah, he's been an enthusiast for many years and started reading Polt's typewriter blog more than a decade ago. He said Polt has helped to shape the typewriter revival and continues to do so. This year, Polt was the keynote speaker at a large online gathering of typewriter enthusiasts, Virtual Herman's.

"Upon first reading the Typewriter Manifesto, contained within the book, I took it to be a somewhat tongue-in-cheek way to explain the usefulness of these outdated machines in our high-tech culture," Van Cleave said. "But as I reread the book, and observed people react to the Manifesto, I noticed there was a more serious undertone present, that I eventually connected with parallels to the 2013 Edward Snowden revelations pertaining to issues of personal privacy in a digital society."

Polt has written on privacy in philosophical work. He said in his letters that typewriters offer a privacy in writing some young people have never enjoyed. He sees this in his students.

"They grow up in some fear that their mistakes on social media will be frozen in amber and used against them decades from now," he wrote to me. "But this is their world, and maybe they can't see any alternative."

Adam Henze is the director of the director of literacy programming at Flanner House in Indianapolis. He and his partner, Siren, launched Antiquated Arts Society in 2020, a typewriter business focused on "restoring writers by reacquainting them with the timeless technologies of creativity." Henze said unlike collector's guides or research-driven book, "The Typewriter Revolution" focuses on the modern world.

"Typewriters are no longer primarily used for memos and business correspondence. They are used to write poems and stories. They're not just office machines anymore. They are beautiful works of art to revere and post about on Instagram."

He and his partner take typewriters to community events as a way to spark conversation between strangers.

"No longer are we using these tools in war or the corporate world," Henze said. "We are using typewriters to slow down the grind and play with language. It's one of the most creative ways you can actively live off the grid."

Tools of the past, comfort in the future

Though he's trying to downsize his collection, which at one point swelled to about 300 machines, Polt is just as active in the typewriter community as ever. He volunteers and lends his services to WordPlay in Northside and provides machines to Community Happens Here in Pleasant Ridge.

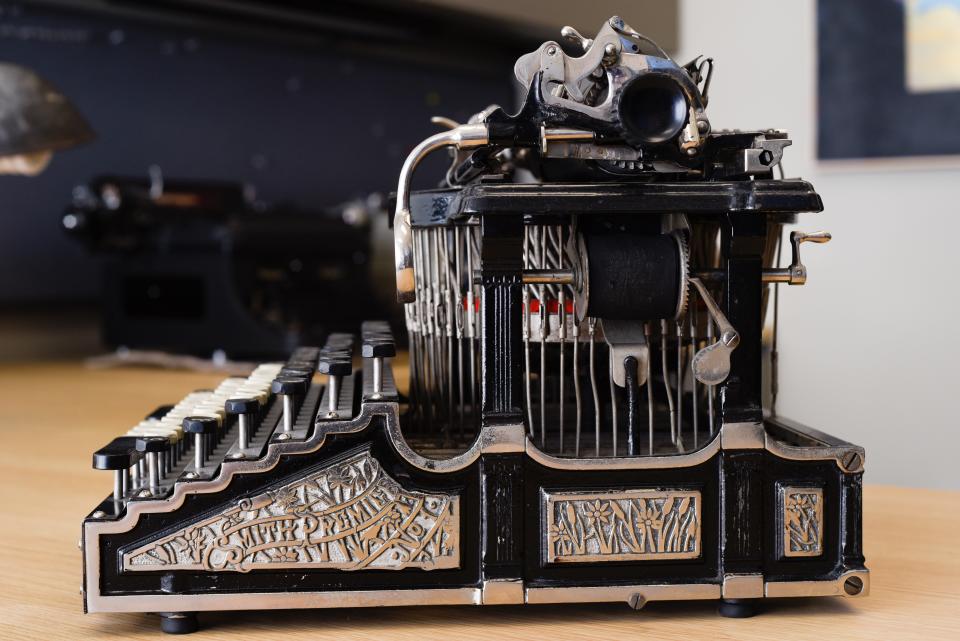

His office at Xavier is lined with typewriters, many of which date back to the early days of the machines in the late 1800s. Some appear to be little more than a nest of metal parts nailed to a plank of wood. Others have all the class and finishing of a grand piano. Every machine had its place there on a shelf and Polt knows the back story of each one. Otherwise, the office has an academic tidiness. His students also have access to his collection, which Polt said they do take advantage of occasionally.

Polt also edits a book series called Cold Hard Type which features typewriter-centric stories and art. He's also searching for a publisher for a novel called "Evertype" about a man trying to escape from digital technology.

In my own small home office, a typewriter now has a permanent place next to my computer desk. The irony of typing by the light of my computer monitor is not lost me. I own several now. There's a joke among typewriter collectors that you should never leave a typewriter unattended in your car because you might come back to find two. For now, there are still a lot of typewriters sitting around in basements and garages unused.

I can attest that a typewriter brings out words in a different way though it might take a late night of clacking away for me to describe exactly how. In a way, Polt summed up the feeling:

"Using the tools of the past helps us understand the worlds from which they came," he wrote. "In this way, we get perspective on our current world instead of accepting it as the be-all and end-all of how to live, or as more 'advanced' than all previous times."

-30-

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: What do vintage typewriters teach us about modern communication?