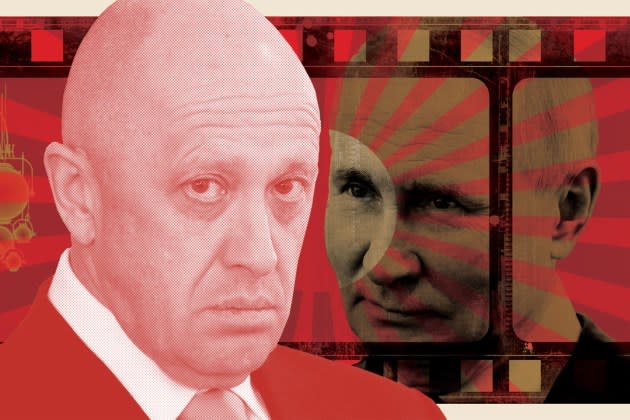

Before He Turned on Putin, Yevgeny Prigozhin Made Hollywood-Style Propaganda Films to Sell His War

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Update: Yevgeny Prigozhin, the former chief of the Wagner group, is presumed dead after a plane he is said to have been aboard crashed on Aug. 23, 2023, killing all 10 passengers, according to Russia’s civil aviation agency. Once one of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s closest advisors, he had been sidelined after mercenaries under his command seized control of the southern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don on June 23, 2023, in the strongest challenge to Putin’s presidency since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Last October, a small Russian production company called Aurum released The Best in Hell, a 107-minute feature film chronicling a brutal struggle for territory in an unnamed European city. The scenes of urban warfare are visceral and raw, and the only respite from the violence comes in the form of periodic tactical lectures aimed directly at the viewer.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

The setting for The Best in Hell is the current war in Ukraine. Online detectives seem to disagree about which of the war’s recent battles the movie is based on. Some believe it’s a re-creation of the 2022 siege of Mariupol, in the disputed Donetsk region, in which thousands of civilians perished in a three-month-long battle that the Red Cross later described as “apocalyptic.”

Others think it refers to the battle of Popasna where, once the fighting had ended, the severed head and hands of a Ukrainian prisoner of war were discovered impaled on a wooden pole. Released online, the movie received wide coverage and was lauded for its realism.

The Best in Hell was shot, edited and released while the actual combatants and survivors of the battles in Mariupol and Popasna — both of which ended last May with Russian victories — were still collecting and mourning their dead. Seen in that light, the most striking feature of The Best in Hell is that it exists at all.

That a current event of such magnitude and tragedy was so quickly and seamlessly transformed into stylized movie fare is a feature of what former national security adviser H.R. McMaster calls “Russian new generation warfare.” Other experts who study Russia have described this dynamic more simply: hybrid war.

Since coming to power in Russia two decades ago, Vladimir Putin has engineered a massive propagandistic operation that stretches across Russia’s billion-dollar film and TV industry into a global network of state-run disinformation-as-journalism and on to the mysterious online world of right-wing mercenary worship known as the Wagnerverse. Mason Clark, the Russia Team lead at the Institute for the Study of War, in Washington, D.C., notes that as Putin’s global influence operations have expanded over the past two decades, and as his intentions to restore both the landmass and the stature of the former Russian Empire have become clearer, “the pool of assets engaged in national security” has grown in tandem to encompass “all of Russian society, including government, business, culture and media institutions.”

To get a sense of just how blurred the lines between the imperatives of the security state and Russian pop culture have become, look no further than The Best in Hell. Aleksey Nagin, who co-authored the script, was no ordinary screenwriter. He was a former Russian soldier turned professional mercenary for the Wagner Group, a notorious private military company that functions as a de facto wing of the Russian military. Wagner is responsible for battlefield atrocities in Ukraine, Syria, Libya and nearly two dozen African countries. In 2021, the United Nations accused Wagner of war crimes, including “torture” and “summary executions.” The group has been the target of recriminations and sanctions, to no effect.

As a member of one of the Wagner Group’s elite assault detachments, Nagin fought in multiple battles in Ukraine and was wounded several times. Last September, just weeks before The Best in Hell was released, Nagin was back on the real front lines, this time in the Eastern Ukrainian city of Bakhmut, where fighting continues. In late September, Nagin was killed. After his death, the Russian government posthumously awarded him its highest honor, the Hero of the Russian Federation. But while Nagin spent his life as a professional killer, his most enduring legacy will likely be a piece of propaganda.

***

The Best in Hell and other similar Wagner movies remain noteworthy for the outsized impact they wield in the burgeoning information war. Another Wagner title, 2021’s Tourist, chronicles the group’s activities in the Central African Republic. It was released in Russia and later in CAR, to a sold-out audience. “These are Hollywood like productions,” said Jason Blazakis, director of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism, and an expert on Wagner’s activities, including its forays into moviemaking. “Their [high] ratings on IMDb are quite problematic.”

Blazakis offered that observation in March in Washington, D.C., during congressional testimony held by the U.S. Helsinki Commission titled “Countering Russia’s Terroristic Mercenaries,” which focused specifically on Wagner’s activities. It is a sign of just how powerful Wagner has become in recent years that American lawmakers are trying to curb the group’s reach. In 2021, the U.S. government designated Wagner as a “transnational criminal organization” and placed its leader, a former hot-dog vendor named Yevgeny Prigozhin, on a Most Wanted List. Neither move made much of a dent.

However, in February, U.S. lawmakers further ratcheted up the pressure by introducing the “Holding Accountable Russian Mercenaries” (HARM) bill in the Senate. If the legislation passes, the United States will officially designate Wagner as a foreign terrorist organization, or FTO, an extraordinary step that would give the U.S. unparalleled economic and legal leeway to go after Wagner, Prigozhin and any person or company that does business with them, both in the U.S. and abroad.

Aside from Putin himself, no one has emerged as a more powerful force in Russia’s information war than Prigozhin. His transformation from petty criminal and prisoner to warlord and movie producer is emblematic of the twisting contours of the hybrid war. Born in 1961, Prigozhin was raised in St. Petersburg. In the early 1980s, he was convicted of armed robbery and fraud and spent nine years in a penal colony. After his release in 1990, he built a network of construction and food catering companies and soon racked up an impressive array of prominent clients in the worlds of politics and business, including the soon-to-be president, Vladimir Putin.

A savvy political operator, Prigozhin cultivated the relationship and earned a spot in Putin’s inner circle, along with the nickname “Putin’s chef.” Behind the scenes, Prigozhin worked quietly to advance Putin’s agenda. In 2014, he created the Wagner Group, a private army of roughly 1,000 mercenaries. That year, he sent them into battle alongside the Russian army in support of Putin’s illegal annexation of Crimea.

In 2019, Prigozhin began producing blockbuster war movies. The heroes of many of his feature films are based on the mercenaries he controls, with Putin’s support, in Russian-sponsored military activities across the globe. Prigozhin’s films are a slicker, higher-octane version of the so-called boeviki movies of the late 1990s, cheap, Rambo-style action flicks that, all available evidence to the contrary, somehow managed to spin the Soviet Union’s inglorious defeat in Afghanistan in 1989 as a triumph. Wagner productions further Russia’s current objectives, subverting the successful Hollywood action movie trope and casting the Russians in the role of the “good guys,” uncovering evil plots and foiling the rapacious appetites of a succession of evildoers who invariably look and act like American capitalists. “It’s the boeviki model, but with more money and more Hollywood inspiration,” says Marlene Laruelle, who directs the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at George Washington University, and who has studied Wagner extensively.

In Shugaley (2020), the first of what would become a trilogy, Prigozhin focused on a real figure, Maxim Shugaley, who had worked for Prigozhin as the director of the Internet Research Agency, a notorious Russian troll factory based in St. Petersburg. U.S. officials believe Shugaley helped interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections by using the IRA and its affiliated companies to spread disinformation and sow public discord through fake social media accounts. Libyan authorities arrested Shugaley and another Russian in 2019, allegedly on suspicion of attempting to interfere in elections there.

When Libyan prosecutors charged the real Maxim Shugaley and his translator in 2019 with espionage, Prigozhin successfully enlisted the help of several Hollywood actors, including Charlie Sheen, Vinnie Jones and Dolph Lundgren, to publicly come to Shugaley’s defense. “Do not give up,” Sheen crowed in a clip he posted to the video-sharing platform Cameo, which allows any of the 30,000 or so celebrities who are members to send personalized messages to their fans. “Freedom will come!” The clip has since been removed after the actors were contacted by the magazine Foreign Policy. A representative for Jones said at the time that the actor received $300 from an unknown donor to make his video. Shugaley was eventually released and later returned to Russia.

Similar films soon followed, featuring Russian soldiers forced to save the world from destruction. In 2021, Prigozhin released Granit, in which an eponymous hero leads a band of Russian mercenaries against Islamic terrorists in Mozambique. The ensuing battle leads the hero to utter a line that could have been cribbed from any number of Hollywood war flicks: “It’s not scary to die for the Motherland, it’s scary to lose it.” The storyline of the 2021 Wagner production Blazing Sun, which featured mercenaries fighting to keep Ukraine’s government from committing genocide, read more like a blueprint for the real invasion that occurred the following year.

The aesthetic displayed in the low-budget Wagner movies, what Laruelle describes as a culture that “admires survivalism, mercenaries, and non-Asian martial arts,” quickly spread online. In the Wagnerverse, which exists primarily on Telegram, YouTube and Instagram, fans of the mercenary life can bond over Russia’s state-sponsored mayhem and buy the merchandise — T-shirts and patches — that celebrates it. One online Wagnerverse community calling itself “Reverse Side of the Metal” is a gathering platform for the mercenaries themselves.

Making movies didn’t prevent Prigozhin from making war — just the opposite. Prigozhin has made himself indispensable in Putin’s war in Ukraine. Wagner troops have borne the brunt of the fighting in some of the war’s fiercest battles, including the bloody siege of Bakhmut. Last September, a grainy video surfaced showing Prigozhin addressing convicted felons at a penal colony several hundred miles east of Moscow. He offered them early release from prison if they signed up to fight in Ukraine. “Who do we need?” Prigozhin barked, “We need shock troops!” Volunteers would receive a presidential pardon after six months of service and, if needed, a burial at the site of their choosing. He gave them five minutes to decide.

In the months since that video was released, Prigozhin has sent tens of thousands of these prisoners to front lines in Bakhmut and elsewhere, using them as cannon fodder in so-called “wave assaults” designed to overwhelm Ukrainian lines. U.S. officials have estimated that as many as 20,000 Wagner soldiers have been killed or injured since the war began. Deserters have been executed. When the Ukrainians sent a Wagner felon back to Russia as part of a prisoner exchange, Wagner soldiers executed him, bludgeoning his head with a sledgehammer, according to a video that was later released. “A dog’s death for a dog,” Prigozhin said in a statement.

Wagner’s onslaught in Ukraine has met with mixed results. Months of fighting in Bakhmut have destroyed the city and killed tens of thousands on both sides. But even as droves of Wagner fighters die in battle, movies like The Best in Hell continue to boost the group’s image, allowing Prigozhin to further expand.

“We see the value [of The Best in Hell] chiefly as an effort to build the Wagner brand,” says Blazakis in an email to The Hollywood Reporter. “It is twisted, warped, but effective with many Russians, sadly.” And not just Russians. According to Blazakis, Wagner has used the movies to successfully find new recruits in Iraq, Syria and Venezuela. Western intelligence agencies estimate that Wagner numbers have grown to more than 50,000 fighters.

In a move reminiscent of the old Soviet youth guard, Prigozhin established the Little Wagnerite, an offshoot targeting Russian youth. With each of these moves, Prigozhin is emerging from the shadows, becoming in the process a loud and vehement driver of Russia’s expanding information war. “The fact that Wagner also spends money on sophisticated Hollywood style propaganda glorifying Russia makes it clear that the group is not there just for economic spoils but also to project Russian power abroad,” said Justyna Gudzowska, former attorney-adviser for the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, during congressional hearings in March. In recent months, Wagner began an even more aggressive massive public relations push, declaring its intention to open 42 recruitment centers across Russia in a bid to find fresh bodies for what Putin has called “the long war” of Russia against the West.

***

Not so long ago, Russia’s views toward the West and NATO were decidedly less hostile. By the end of the ’90s, Putin himself, then still the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, was informally floating the idea of Russia joining NATO, declaring at one point that Russia’s future was to be found in a “wider Europe that is not divided by walls of any kind.”

As NATO continued to expand eastward, however, accompanied by increased military presence in the Balkans and within Russia’s other historic spheres of influence, Putin’s enthusiasm began to sour. As early as 2001, during Putin’s first year of power, then-minister of Press, Broadcasting and Mass Communications Mikhail Lesin returned from a trip to the U.S., dismayed by the grim way Russia was portrayed. “We need to propagandize Russia in the international market,” he announced, “or we’ll look like bears in their eyes, wandering the streets growling.”

With Russia still economically weak, and strategically diminished, Putin turned to an area of operations he had mastered as a former spy: psychological and information operations. Culture was a powerful propaganda tool, but the world of high Russian art was another story entirely. For the first several years after coming to power, Putin treaded carefully, mindful of the immense shadows cast by auteurs like Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Eisenstein. “In the beginning Putin, was trying to create something to share,” says Laruelle. “They were figuring out how to use culture to legitimize the regime and create a sense of shared belonging.”

Moviemaking in Russia is often dependent on state-sponsored largesse, specifically from the Ministry of Culture and Fond Kino. Aware of its vulnerability in Putin’s early years in power, the government welcomed an array of pitches and scripts, including for festival contenders that were openly critical of the regime. Russia’s chaotic emergence from Soviet communism was creating immense opportunities, and Hollywood was paying attention. In 2002, the American-British billionaire Len Blavatnik invested $45 million in Amedia Productions with Russian producer Alexander Akopov, producing the period drama Poor Nastya, at the time Russia’s most expensive TV production. Blavatnik’s investment foretold a surge of foreign money and interest into the Russian market.

However, other forces were also emerging. Facing widespread discontent early in his second term, Putin needed loyal soldiers to help quell dissent. In the spring of 2012, Putin appointed Vladimir Medinsky, a regime loyalist and self-described advocate for traditional values, as minister of culture. In the eyes of nationalists like Medinsky, successful movies glorified Russia, even as they sidelined voices the regime viewed as subversive. “You could get quite a bit of public money to make a movie in Russia,” says one Russian director who is currently living in exile in the West, “if it was patriotic.”

Under Medinsky, the Ministry of Culture focused on the three achievements of which Russia could be proudest: its victory over the Nazis in “The Great Patriotic War,” as World War II is called in Russia; the accomplishments of Yuri Gagarin and other Russian cosmonauts; and Russia’s triumphs in the sporting world. In 2013, the government injected $300 million to refurbish and rebrand the decrepit state-run studio Mosfilm as a Hollywood rival. Medinsky published a list of approved subjects that cash-strapped producers might consider, including “exemplary labor,” “traditional values” and “heroes fighting crime, terrorism and extremism.”

Medinsky’s efforts led to some Orwellian outcomes. One evening in the winter of 2012, an American screenwriter and his wife took their seats inside an elegant Moscow movie theater, just down the street from Red Square. The screenwriter had spent the previous two years researching and writing what he described as an “interesting, imaginative war movie” set in the hills of South Ossetia, where Russia was fighting Georgian separatists. That evening was to be his Russian debut. No sooner had the theater lights dimmed, however, than things onscreen took an unexpected turn.

The screenwriter watched as a handsome and confident Russian president laid out a bold plan of action to save the day. There was only one problem: His script didn’t feature a Russian president, or a bold plan of action. More such scenes followed, each more galling than the last. The insipid, jingoistic fare was turning what had been a “completely apolitical” movie into a potent piece of state propaganda. “We have to get out of here,” he whispered to his wife. During the afterparty, the movie’s Russian director asked the screenwriter if he thought they could get international distribution. “Sure,” the American replied, “if you take out the four fucking scenes that turned this into a piece of propaganda.”

Looking back, the screenwriter sees signs he didn’t discern at the time. “I get the sense now that this was all part of an organized tactic,” he says. “I think there was a concerted effort that ramped up to take hold of the arts, movies, and use them to serve the larger propaganda purposes of the state. I can’t help feeling like a quisling.”

Soon enough, Medinsky was organizing televised banquets between Putin and appropriately patriotic directors. In 2014, Russian viewers tuned in to watch Putin and the celebrated director Fydor Bondarchuk sipping tea while Putin lectured the audience about the importance of showcasing Russian accomplishments. Bondarchuk proved to be an early and reliable Putin backer. In 2014, he publicly supported Putin’s annexation of Crimea. But even as his aesthetic choices clearly aligned with Putin’s, Bondarchuk took issue with the idea of state interference. “They listen to us,” he insisted to The Guardian in an interview following the release of his globally successful World War II epic Stalingrad, which celebrated Russian stalwartness. “I can’t remember any stories like: Do a super-patriotic movie!”

Nevertheless, more tea parties followed as directors and producers began to fall in line with Putin. A few exceptions were to be found among Russia’s powerful oligarchs, some of whom had begun funding art house movies. In some circles, people even spoke of a “renaissance” in Russian moviemaking, pointing to private financing and distribution deals that continued to wash up on Russian shores. Netflix’s arrival in 2016 foretold the growth of streaming services and other co-production opportunities. Early investors ramped up their activities. Blavatnik, who had upped his profile in the entertainment world with his 2011 purchase of Warner Music Group for $3.3 billion in cash, doubled down on his earlier investments in Russian TV and film. Blavatnik’s company helped produce a Russian remake of Ugly Betty that found distribution in 25 countries. As a foreigner, the Ukrainian-born Blavatnik avoided domestic political squabbles. More recently, Blavatnik, who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s, helped produce A Dog Named Palma, and the 2019 war film T-34.

Less sheltered oligarchs continued to fund and support controversial movies, dodging pressure from the regime with varying degrees of success. The Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich emerged as a steadfast supporter of independent films, contributing financing to director Kirill Serebrennikov’s movie, Tchaikovsky’s Wife, as well as his legal fees when Serebrennikov was imprisoned for running afoul of Kremlin tastes. Even the Ministry of Culture sometimes got behind projects that ultimately ran counter to its stated objectives. In 2014, Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan nabbed an Oscar nomination for best foreign-language film. “That’s one of the paradoxes of the Putin regime,” argues Laruelle. “You can be co-opted and still make good things.”

But with the Ministry of Culture getting involved in some 80 percent of Russian productions, movies about sports, space and war continued to proliferate. When projects offended the regime, a resurgent Russian hammer came down hard. Medinsky didn’t mince words, slamming unsympathetic movies as “anti-Russian” or worse. In 2015, he pilloried Alexander Mindadze’s festival darling My Good Hans as “anti-historical” and tried to rescind government funding. When the Ministry of Culture got wind in 2017 that a movie it had helped fund, Moscow Never Sleeps, included a storyline about corruption, it withdrew financing. “People said, ‘What the hell,’ and began to make movies the government wanted, and they got rich,” says the exiled director. In some cases, the repression took on more extreme forms. After Russian director Aleksey Krasovskiy released Prazdnik, a black comedy, the government came after him. His bank accounts were frozen and prosecutors filed criminal charges.

The war in Ukraine has exacerbated these tensions. The Russian State Duma issued a list of 142 celebrities who hadn’t expressed adequate support for the war. Artists and journalists have been arrested and jailed; critics of the war face years-long prison terms. The cultural boycott of all things Russian has arguably been equally damaging. Hollywood has essentially frozen Russia out of the movie business. Highly anticipated productions, including adaptations of the Russian novels The Master and Margarita and Anna Karenina, are stalled as distributors weigh the potential risks of an association with all things Russian. Apple canceled its first Russian-language TV series, Container. Netflix, Universal and half a dozen other major studios have pulled out. One day last spring, Krasovskiy returned home to find that his front door had been spray-painted with a “Z,” a swastika-like symbol indicating support for the regime and the war in Ukraine. Krasovskiy fled the country and also now lives in exile. Last March, after spending several years on probation and in court fighting embezzlement charges, director Kirill Serebrennikov also fled.

Last year, for the first time since the fall of the Iron Curtain, Russia pulled its entries for the Academy Awards. The chairman of the Russian film academy, Pavel Chukhray, who said he wasn’t consulted before the government announced its decision, called the move “illegal” and protested by resigning. Former Oscar winner Nikita Mikhalkov, whose Burnt by the Sun won best foreign-language film in 1995, had by 2022 risen to become head of the Russian Cinematographer’s Association, and was in favor.

“Cultural policy is already changing,” says Dmitry Shlykov, a Russian cinematographer whose views align with the new nationalism. In written responses to questions, Shlykov expressed satisfaction with the direction Russian cinema is taking. “There will be no more attempts to fit into the Western ‘liberal’ agenda,” he wrote. In fact, he said, even more repressive measures might be needed. “The forces that have been promoting all this for the past 30 years are still quite strong and do not give up their positions without a fight both in the theater and in the film industry.”

Six decades ago, while NASA was still fumbling in the dark, the Soviet Union sent Yuri Gagarin into orbit aboard Sputnik. In 2021, eager to best the Americans again, the Russian Space Agency helped director Klim Shipenko become the first director to shoot a movie in outer space. Tom Cruise and Doug Liman, who were pursuing their own space project, were said to be close on the Russians’ heels. Shipenko spent 12 days filming in zero gravity, 227 miles above the Earth. “Man can fly,” Shipenko said in a recent telephone interview from Moscow. “You float around the earth and you see continents go by one after the other. There’s Africa. Ten minutes later, there’s South America. It’s hard not to see everyone as unified. We’re all the same.”

In the end, Shipenko won the race to movie space. But at what cost? Shipenko was circumspect. He was open about not wanting to say anything that might land him in hot water. “I would be reluctant to say that in public right now,” he said, when I asked about the war in Ukraine. “You know how the situation is in Russia and I’m not going to — and I live here and work here so I can’t really speak about this in the interview.” Before the war in Ukraine, Shipenko was on the brink of signing a worldwide distribution deal with a major studio. “At this point, I don’t know if that’s going to happen,” he said. The film, titled Challenge, topped the Russian box office when it was released in April, but it is unclear if the rest of the world will ever get to see it. “He’s trapped now,” says one person who knows Shipenko. “He fell into a pit with shit.”

***

While the contours of Russia’s information operations will to some extent be influenced by palace intrigue in Moscow, there is little doubt that the propaganda war will continue to expand. In March, for the first time since the war in Ukraine began, Putin ventured out from Moscow toward the front lines. He toured Mariupol, one of the possible settings for The Best in Hell. The day before, the International Criminal Court in the Hague had issued an arrest warrant for Putin on charges of war crimes, and the visit to Mariupol had all the trappings of a propaganda coup. Since then he has taken several more trips to disputed areas close to the Russian front. Wagner’s atrocities on the battlefield, refashioned into heroics in movies like The Best in Hell, have helped earn Prigozhin high approval ratings in national polls.

With every death of a Wagner mercenary, Prigozhin’s own ambitions seem to grow. In recent weeks he has maneuvered to become one of Russia’s most powerful political figures, using his platform to excoriate top Russian generals as “scoundrels” and lambasting Putin’s defense minister Sergei Shoigu for failing to provide Wagner soldiers with ammunition and supplies. He has openly taunted Russian officers engaged in fighting elsewhere that they need to follow the example set by Wagner mercenaries if they hope to “save face” with Putin. In early March, he took aim at Shoigu’s son-in-law, accusing him of being a peacenik and vacationing in Dubai.

Some have speculated that Prigozhin has become so powerful as to pose a direct threat to Putin himself. Prigozhin recently declared that he would transform Wagner, once little more than a rag-tag group of mercenaries, into a full-fledged “army with ideology.” During the battle for Bakhmut, in a March speech delivered against a backdrop of Wagner corpses, Prigozhin threatened to withdraw his soldiers entirely and hinted at even more drastic moves. He reversed course a day later after extracting a promise from the Russian Ministry of Defense for more ammunition. Having secured this new arrangement with the Kremlin, Prigozhin announced that his soldiers had been authorized “to act as we see fit.” In late May, Wagner’s troops broke the brutal, bloody stalemate and declared victory in Bakhmut. So far, no movie has been announced.

This story was first published on June 8 at 7:35 a.m.

Aug. 23, 2:22 p.m.: Updated with statement from Russia’s civil aviation agency regarding a plane crash north of Moscow that it says killed all 10 people on board, including Yevgeny Prigozhin.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter