Inside Tony Bennett's Civil Rights Work, Marching with Martin Luther King Jr. and Liberating Nazi Camp

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The legendary jazz vocalist, who had been quietly living with Alzheimer's disease since 2016, died on Friday morning

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Tony BennettTony Bennett was more than a legendary jazz vocalist. He was also a soldier who witnessed horrors as he fought in World War II and was enraged by racism. As his career skyrocketed and he became a voice of his generation, he never lost sight of what he truly cared about: advocating for equal rights.

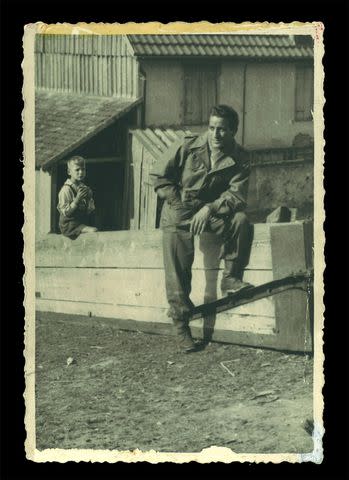

Bennett — who died on Friday at age 96 — was drafted into the U.S. Army at age 18 in 1944. The next year, he was deployed to Europe with the 63rd Infantry Division where he replaced deceased soldiers in the frontlines at the Battle of the Bulge. He opened up about his experience in his 1988 autobiography The Good Life.

Dave Kotinsky/Getty

Tony BennettHis division fought its way across Germany and he was among the soldiers who liberated the Kaufering Concentration Camp, which was the largest subcamp of the Dachau complex. Days later, the war in Europe ended with Nazi Germany's unconditional surrender and Bennett (born Anthony Dominick Benedetto) was sent to Mannheim as a part of the Allied occupation force of postwar Germany.

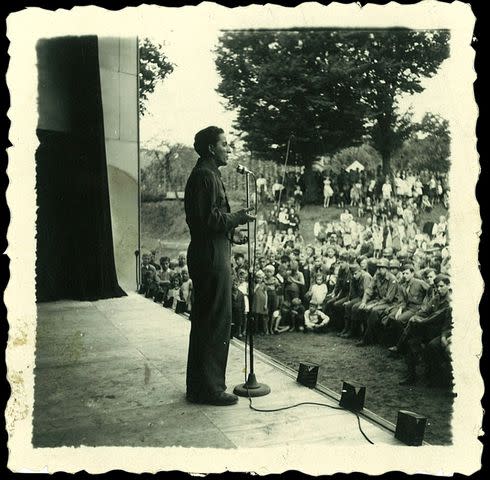

It was there that he first picked up the microphone and would entertain the troops with his vocal talent and began singing with the 314th Army Special Services Band. On Thanksgiving Day, he bumped into an old friend named Frank Smith who he had known in high school and played in a quartet with. They were excited to see each other so they attended a church service and Bennett invited Smith to join him for dinner. However, it wasn't long before they ran into an officer who berated them. (At the time, the military was segregated and they two men were not allowed to be seen with each other).

“This officer took out a razor blade and cut my corporal stripes off my uniform right then and there,” the 20-time Grammy winner wrote in his book, per the Washington Post. “He spit on them and threw them on the floor, and said, ‘Get your ass out of here!’”

TonyBennett.com

Tony BennettRelated: Nile Rodgers, Flea, Rev. Jesse Jackson, More Pay Tribute to Tony Bennett: 'Last of His Kind'

He was then reassigned from Special Forces to Graves Registration, where he dug up the bodies of American soldiers killed in combat for reburial. Later, an Army officer learned what happened and pulled strings to get Bennett back to singing in Europe.

Fast forward to the '50s, Bennett had left the army and began building a career for himself. He became enraged when he witnessed Black musicians like Nat King Cole and Duke Ellington being denied entry to concert hall dining rooms and hotels.

"I'd never been politically inclined, but these things went beyond politics," Bennett wrote in his autobiography, per NBC. "Nate and Duke were geniuses, brilliant human beings who gave the world some of the most beautiful music it's ever heard, and yet they were treated like second-class citizens. The whole situation enraged me."

TonyBennett.com

Tony BennettThis is what fueled Bennett — a tireless civil rights activist — to accept Harry Belafonte's offer to march alongside Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

"When the march started, I had a strange sense of déjà vu," the singer wrote. "I kept flashing back to a time twenty years earlier when my buddies and I had fought our way into Germany."

"It felt the same way down in Selma: the white state troopers were really hostile, and they were not shy about showing it," Bennett wrote. "There was the threat of violence all along the march route, from Montgomery to Selma, some of which was broadcast on the nightly news and really helped to make the country aware of the ugliness that was still going on in the South."

Though he did not walk all 54 miles, he went ahead to Montgomery to greet King and sing for the marchers alongside Ella Fitzgerald, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Sammy Davis Jr., Mahalia Jackson and others.

“I’m enormously proud that I was able to take part in such a historic event,” Bennett wrote in his autobiography, “but I’m saddened to think that it was ever necessary and that any person should suffer simply because of the color of his skin.”

Bennett went on to advocate for Black artists in the music industry and worked for racial equality. He also received the Citizen of the World Award and Humanitarian Award from the United Nations for his civil rights work.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.