Inside Pixar’s Existential Crisis and How It Can Bounce Back After Disney+ Stole Its Mojo

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Elemental” is the quintessential Pixar movie.

The company’s latest animated wonder takes place in a cleverly imagined city populated exclusively by anthropomorphic elements in which two characters made of fire and water meet and fall in love. That whimsical logline is enough to recall “Inside Out” and “Monsters, Inc.,” beloved Pixar classics from an earlier era that some see as the company’s heyday. The technology that brought “Elemental” to life is also deeply indebted to the culture and history of the studio, pushing its capabilities to the very limits of possibility. “Elemental” director Peter Sohn told TheWrap that at one point Pixar servers were strained so hard they started smoking.

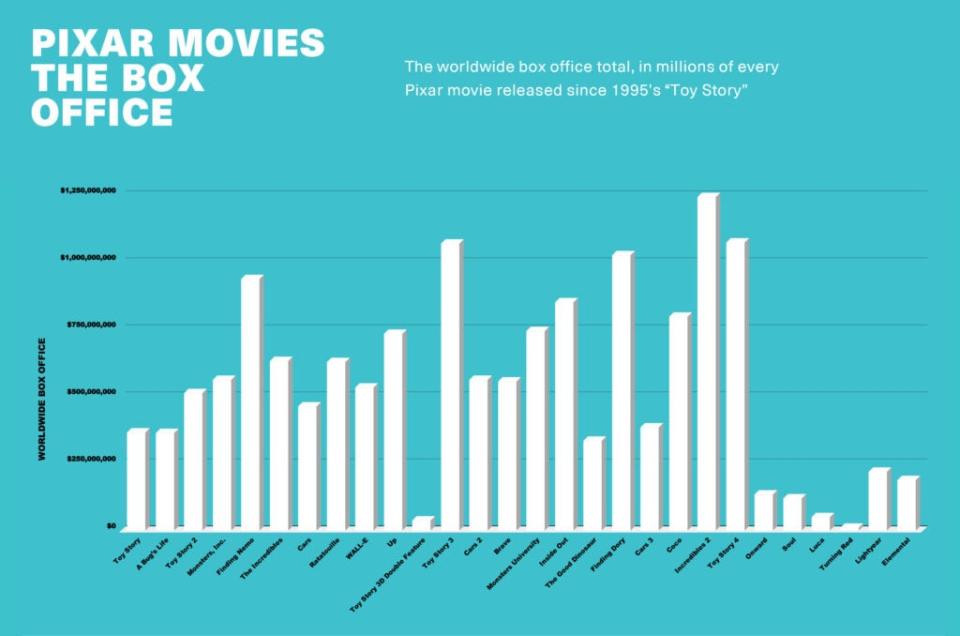

But “Elemental” isn’t pushing box-office boundaries like those earlier Pixar triumphs.

Over its opening weekend, “Elemental” made $29.6 million, which is enough to carry the distinction of being the worst three-day Pixar opening ever, taking inflation into account. Warm critical notices and a five-minute standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival didn’t seem to draw in the moviegoers Pixar has long courted.

Also Read:

‘Elemental’ Is Shaping Up to Be Another Pixar Flop

“Elemental” was an attempt, after a wobbly few years defined by a dramatic change in leadership and a global pandemic, to recapture the Pixar magic that audiences all used to feel, the sensation that would prompt moviegoers, young and old, to race to the theater and get a ticket, the reputation that every Pixar movie was a must-see event.

The problem: The pandemic, and Disney’s response to it, broke the habit. Three of Pixar’s most recent movies arrived without much fanfare on Disney+. In a recent ad, Pixar’s marketers seemed to acknowledge this struggle to convince moviegoers to not wait for streaming, calling on them to come back to theaters for the “Pixar experience” the studio has delivered for more than a quarter-century.

Grab your

and prepare to

with another amazing Pixar experience with #Elemental, only in theaters June 16!

— Pixar’s Elemental (@pixarelemental) May 28, 2023

Does the commercial failure of “Elemental” mean that the special alchemy that made Pixar movies so special is gone? The New York Times wrote gravely of the opening-week tally: “Pixar is damaged as a big-screen brand.” What’s causing the bulb in the studio’s Luxo Jr. lamp to start blinking? And is there any hope that the magic can be restored?

Pixar declined a request for comment, but TheWrap spoke to multiple current and former employees, who said a frenzied push to create more content for Disney+, paired with a much different approach to the development of material by Pixar leadership under Pete Docter, who has been chief creative officer since 2018, and a loss of institutional knowledge thanks to company stalwarts either leaving or getting laid off, puts Pixar in a dangerously precarious spot.

Also Read:

Pete Docter Opens Up About the Past, Present and Future of Pixar

A mostly happy history of failures

The legendary studio has been in similarly tricky positions many times before and always managed to find a way out and produce some of the most beloved, boundary-pushing animated films of all time.

But things are much harder these days.

When Pixar began, it wasn’t comprised of world-class, Oscar-winning filmmakers. The team was a ragtag bunch of programmers and cartoon enthusiasts at George Lucas’ effects house Industrial Light & Magic whose wild-eyed zealotry for the unproven medium of computer animation and the technology that went along with it was enough to force Lucas to sell the unit off. For Lucas, a man whose restless innovation has shaped seismic changes in the industry, this decision might seem incredibly short-sighted. But Lucas was going through a divorce and needed the money.

What’s even more shocking — and rarely talked about — is that Disney had a chance to buy Pixar from Lucas. The asking price? $15 million. Then-Disney President Jeffrey Katzenberg couldn’t be bothered. Steve Jobs, the once and future Apple mastermind, stepped in.

Still, Disney and Pixar had a relationship from early on. Pixar helped develop CAPS, or Computer Animation Production System, which revolutionized the way Disney’s animated features were assembled and painted. (It was first implemented for an entire production on “The Rescuers Down Under” in 1990 after a single test shot in 1989’s “The Little Mermaid” proved promising.) While working on “The Rescuers Down Under,” then-Walt Disney Feature Animation (as it was known) President Peter Schneider proposed making Pixar’s first feature-length animated film. That film would become “Toy Story.”

And while we now remember “Toy Story” for what it is — a groundbreaking technical accomplishment and a storytelling triumph, winner of a Special Achievement Academy Award and the foundation of a rich franchise that is still going today — it was a messy, troubled production full of creative dead ends and forced studio intervention.

Then there was the time the entire working copy of “Toy Story 2” got deleted thanks to a stray Unix command. Or the time the studio decided it had to start over from scratch on “The Good Dinosaur.” As Wired once put it, “a truer history of Pixar might be described as a repeated string of failures, occasionally punctuated by the release of a hit movie.”

The difference is this: For the first decade-plus of Pixar’s film output, the pace was slow, and the company had time to recover from its mistakes. Its second feature, “A Bug’s Life,” didn’t open until 1998, a full three years after “Toy Story.” And these early productions were all hands on deck. Many of the chief creative forces of Pixar — among them John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Docter, Lee Unkrich and Joe Ranft — worked on each project, challenging each other’s ideas and learning how to make movies in the process.

According to several Pixar employees, “Toy Story 2,” released in 1999, was the pinnacle of this early approach. Initially meant to be a direct-to-video follow-up to the original, Lasseter saw potential in a big-screen sequel and jettisoned an earlier attempt. All of Pixar rallied and they released the movie a year after “A Bug’s Life,” producing the rare sequel that topped the original critically and financially.

Even so, there were doubts. In August 2002, just before the release of “Finding Nemo,” Disney CEO Michael Eisner sent a note to his board members: “Yesterday, we saw for the second time the new Pixar movie ‘Finding Nemo’ that comes out next May. This will be a reality check for those guys. It’s OK, but nowhere near as good as their previous films. Of course, they think it is great. Trust me, it’s not, but it will open.”

After opening in the summer of 2003, “Finding Nemo,” directed by Stanton and co-directed by Unkrich, became the most successful animated film of all time.

Even during the golden era of the company, disaster frequently visited: In 2005, Ranft was tragically killed in an automobile accident at the age of 45; “Ratatouille” went through a dramatic creative overhaul shortly before release that saw the original director removed and replaced by Brad Bird; with negotiations between Pixar and Disney breaking down, Disney started working on its own sequels to Pixar films while Pixar looked for another suitor (eventually Jobs sold the company to Disney in 2006 for $7.4 billion). Directors were replaced, projects canceled and an entire stop-motion studio, led by Henry Selick, crashed and burned, leading to an $80 million write-down for Disney.

But throughout all of this, those initial filmmakers — including Docter, Stanton, Unkrich and Bird — were there, making sure that the brand was never tarnished, steadily releasing a single film every year until 2015, when unexpected production problems forced “The Good Dinosaur” to be released the same year as “Inside Out.”

A generational shift

In 2017, Lasseter took a six-month sabbatical after accusations he had inappropriately touched female colleagues. In June 2018, he was gone. Docter, the brainy filmmaker behind “Up” and “Inside Out,” would step in to replace him. In a 2021 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Docter said: “I did wonder, ‘If I say no, what happens?’ I don’t want to seem too self-aggrandizing here, but I wasn’t sure who else would do it. And so I said yes.” At the time, it seemed like the biggest shake-up in the studio’s history.

And then came Disney+.

Launched in November 2019, Disney+ was the company’s direct-to-consumer streaming service, its Wall Street-pleasing answer to Netflix.

Quickly, the company leaned on all of its divisions for more product to feed its new streaming beast — including Pixar, which would be called upon to provide shorts, series and documentaries.

Just a few months later, the world would grind to a halt in the shadow of a looming pandemic. “Onward,” Pixar’s spring 2020 movie, would have the misfortune of opening less than a week before theaters would shut down due to COVID-19. It would only make $142 million worldwide before a swift move to premium video on demand (PVOD) and, crucially, Disney+ after that.

In the years that followed, three of Pixar’s most artistically ambitious and commercially viable movies arrived exclusively on the streaming platform (“Soul” in 2020, “Luca” in 2021 and “Turning Red” in 2022). Audiences were conditioned to expect Pixar fare on Disney+. Pixar employees, including Docter, were outraged, with many speaking out against the practice of putting new Pixar movies on Disney+, a move pushed by former CEO Bob Chapek.

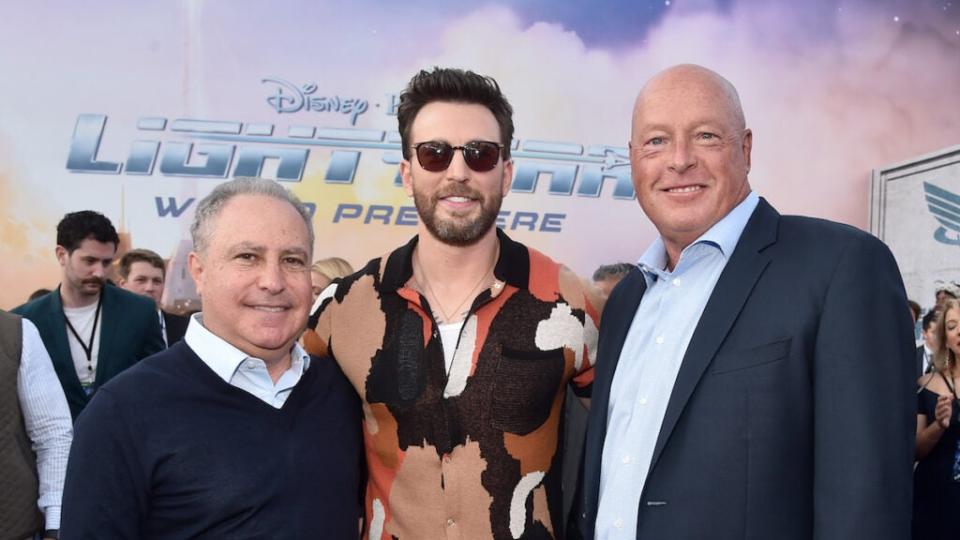

When “Lightyear” opened theatrically last summer, it seemed like a sure bet — a novel concept that expanded the “Toy Story” franchise. It starred Chris Evans and was directed by Angus MacLane, a longtime Pixar vet who had helmed several “Toy Story” spin-off projects and co-directed “Finding Dory.” But when it finally opened, it underperformed.

A lackluster and muddled marketing campaign for “Lightyear” certainly contributed to the film’s financial shortfall, as did a surprisingly crowded market which kept the film out of premium screen formats. Internally, Pixar saw a direct connection between how the previous three films were delivered and how “Lightyear” was received. Both box office prognosticators and those actually making the movies asked the same question: Why would audiences rush to movie in theaters when they knew it would be on Disney+ soon enough? And they were right — the movie showed up on the direct-to-consumer streaming platform on Aug. 3, less than three months since the movie’s theatrical debut.

Now “Elemental” seems to be doing even worse.

Beyond Disney+, there are two huge factors impacting Pixar right now.

One is Docter’s management of the studio. Instead of making one movie every couple of years, the studio is now cranking out at least one movie a year, sometimes two, plus all of the additional supplemental content for Disney+, including “Win or Lose,” a full-fledged animated series coming later this year. The workload has never been greater and those at Pixar have never been stretched so thin, according to those we spoke with.

Those who have worked for both creative leaders describe Docter’s style as more cerebral than Lasseter’s, with Docter putting a premium on the filmmaker’s personal experiences over movies with more outward scope and commercial appeal.

“Luca” recounted filmmaker Enrico Casarosa’s childhood experiences growing up in a small coastal Italy town, embellished with magical realism and a romantic, postwar setting; “Turning Red” dramatized director Domee Shi’s adolescence in turn-of-the-millennium Canada with a similarly fantastic overlay; and “Elemental” sees filmmaker Peter Sohn recount his experience as the son of immigrants, only set in a sprawling metropolis filled with anthropomorphic elements.

Also Read:

How ‘Turning Red’ Avoided Chinatown Clichés

Pixar’s next film, March 2024’s “Elio,” continues the trend, with Adrian Molina (a co-director of “Coco”) telling an autobiographical story of a self-described “indoor kid” who winds up getting abducted by a group of colorful aliens.

Those interviewed by TheWrap, all of whom admire Docter, noted that his style is in stark contrast to Lasseter’s, who would throw out constricting frameworks and force filmmakers to rise to the challenge to make them great. (He famously had a rule about never allowing nonhuman and human characters to verbally communicate.) But some have suggested the importance Docter puts on personal stories has robbed the studio of some of its ambition and appeal, which is a problem when the movies cost so much.

Can Pixar sustain $200 million personal stories that double as therapy sessions for their very talented directors? Sohn admitted, when we spoke to him a few weeks ago, that there were times when he felt too close to the story of “Elemental.” “I had heard stories that there’s a danger that when you do something personal, you’re going to start to lock down and you won’t let it evolve… there are moments of the film where it was like that for me,” Sohn said. “And you know, I lost my dad early on in the development and I started getting really tight about things, which I didn’t know consciously was going on.”

In contrast, those earlier, more successful Pixar movies often hinged around simple, ingenious concepts that were childlike in their fantasy: What if toys came to life when you weren’t looking? What if there really were monsters in your closet? What if humans left Earth but forgot to turn off the last robot?

Also Read:

‘Turning Red’ Director Domee Shi Finds Fresh Ideas by Trusting Her ‘Weird Gut’

The other problem is that the institutional knowledge of the company has eroded over time. “It has always been my goal to create a culture at Pixar that will outlast its founders,” wrote Ed Catmull, one of Pixar’s co-founders, in his book “Creativity, Inc.” Catmull left the company in 2018 and stayed on as an advisor until the end of 2019.

It’s hard to know if Catmull has achieved that goal. He and Lasseter are gone. (Towards the end of his tenure, Disney paid out $100 million to settle accusations that Catmull had orchestrated a wage-fixing scheme to cap animators’ salaries.)

Docter is now running the company. Stanton is away making a live-action feature for Searchlight and also directed episodes of Netflix’s upcoming “3 Body Problem.” Unkrich is mostly gone but occasionally consults. Bird is at Skydance Animation, reunited with Lasseter. MacLane, longtime producer Galyn Susman — the one who saved “Toy Story 2” — and director Steve Purcell (co-director of “Brave”) have all been forced out during a recent round of layoffs.

There are a new crop of filmmakers currently making movies at Pixar and the group is both younger and more diverse. According to the studio’s slate, there are movies scheduled through at least 2026. As an animation historian who recently co-wrote a two-volume book about Imagineer and animator Marc Davis, Docter realized how badly Disney Animation suffered when the Nine Old Men, Walt’s original group of animators, outstayed their welcome and lost their touch.

Some have already been elevated to leadership positions, like “Turning Red” producer Lindsey Collins, now senior vice president of development, and Shi and Sohn, who are creative vice presidents. The tight working relationship between Shi and Collins is rare these days, but it speaks to the effectiveness of the partnership that it produced one of the greatest Pixar movies ever in “Turning Red.”

Collins, who also worked on “Wall-E,” is a 26-year veteran of the company. But some insiders worry that many of Pixar’s younger, more inexperienced filmmakers don’t have the necessary guidance and leadership. Instead of close-knit teams working throughout a single production, the sheer volume of content that Pixar is now responsible for and the highly competitive environment mean that key creative people will usually not stay on a project all the way through completion. Instead, they’ll hop onto the next thing, leaving that original project to suffer and the filmmakers in charge of the projects even more adrift.

“Win or Lose,” the new longform Pixar series, is set to debut in December on Disney+. We’ve seen some of it and it feels like one of the bolder things the studio has produced in years. It’s using a lower budget and simplified designs to its advantage without losing any of the trademark Pixar emotionality. It is striking. And it was conceived and directed by Carrie Hobson and Michael Yates, two talented young storyboard artists from “Toy Story 4” who represent the younger, more diverse new crop of talented filmmakers at the studio.

But the creative success of the show is not an indication that the relationship between Disney+ and Pixar has gotten any easier. A follow-up series from Pixar has been quietly canceled. It might get reworked as a feature film later.

Also Read:

The Alternate Versions of Pixar’s ‘Turning Red’ That We’ll Never See

Where Pixar needs to go

So where does Pixar go from here?

One of the best things it can do is invest in new, young talent whose stories could propel Pixar once again to greatness. But can they prosper without guidance from the original Pixar crew?

Maybe the expectation associated with Pixar has to change. Few of the things that made Pixar the brand it is still remain. Not to get too philosophical, but are the Beach Boys still the Beach Boys if it’s Mike Love and four session guys?

Making the movies cheaper isn’t going to help. The staff is already overworked, and the movies still take a lot of time: “Elemental” was in production for seven years.

Pixar might benefit from simply slowing its roll. Disney has already mandated less spending (which equals less content) and the demands from Disney+ has ebbed. Fewer Pixar productions means that each individual film will carry that much more weight. A Pixar movie could feel special again.

And eventually, schooled by their own failures, this new crop of Pixar talent may become seasoned vets. They may help Docter (and whoever comes after him) run the place even better and maybe more efficiently. And if all else fails, they have a few sequels up their sleeve, like next summer’s “Inside Out 2” and a fifth “Toy Story” film.

Pixar is something special. Maybe it just needs to remember that.