Inside the Dark Fantasy of Hotel Life

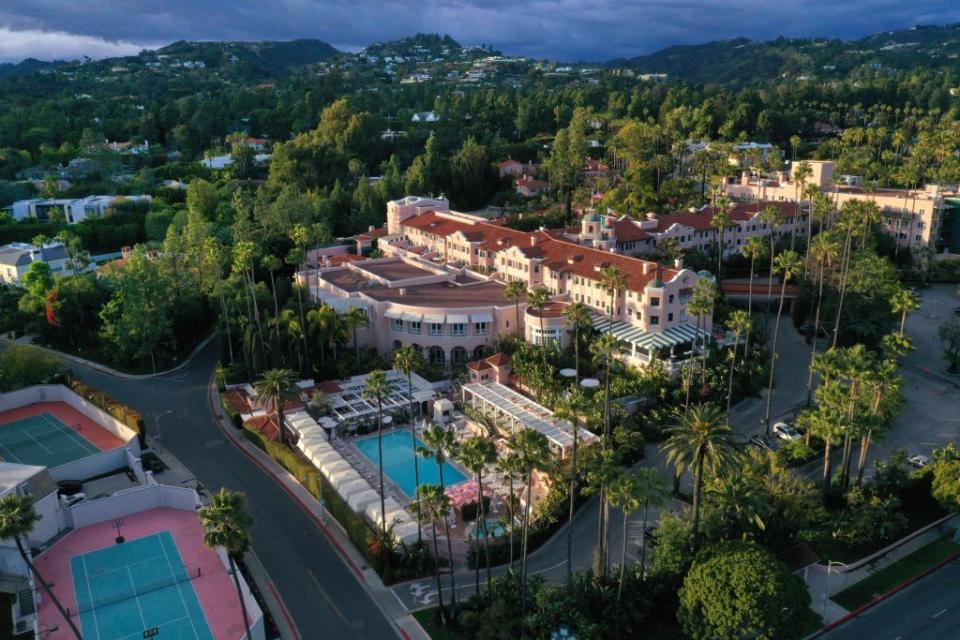

When Liska Jacobs set out to write her latest novel, The Pink Hotel, she went full “method writer,” immersing herself in the set and setting of the story. It wasn’t too much of a hardship: the novel takes place at the legendary Beverly Hills Hotel, where Hollywood elites have hobnobbed since its opening in 1912. Just a month before Covid-19 shut down the world, Jacobs spent a week in luxurious seclusion at the property, where her days were filled with swimming, dining, and people-watching. As she reveals below, the transformation was almost instantaneous.

The Pink Palace, where the Rat Pack drank themselves under the table and the Beatles slipped in through the back for an after-hours dip, has long had this transformative effect on its well-heeled guests. Jacobs’s novel opens in contemporary times, when two astonished visitors roll up to the red carpeted entrance: Kit and Keith Collins, a newlywed couple from small-town California. Kit and Keith have been invited to honeymoon here by Mr. Beaumont, the general manager who hopes to hire Keith as his lieutenant. Charming, upwardly mobile Keith will do anything to land the job, but Kit fails to see herself in her husband’s opulent vision for their married life. “It’s fine to be the passenger when you trust the driver,” she muses, “but now, doubts have reared and questions gnaw.”

Meanwhile, dangerous wildfires sweep through Los Angeles, along with violent riots and rolling blackouts. The Pink Hotel closes its doors to “outsiders,” trapping Kit and Keith with disgruntled staffers and ultra-wealthy eccentrics. In skeptical longtime waitress Coco, Keith finds a powerful enemy; elsewhere, in young and monied Marguerite, Kit discovers a companion who may or may not see her as more than a working class plaything. As tensions rise, the guests’ boredom finds ever-escalating outlets, from grotesque hedonism to unconscionable absurdity.

In this glittering satire about greed, excess, and human folly, Jacobs takes aim at our tenuous class system and sinks a kill shot. She spoke with Esquire by Zoom to take us inside the novel, from her research process to the ethical challenges of travel. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Esquire: Where did this book begin for you?

Liska Jacobs: It’s based on an actual event that happened during the LA riots in 1992. All the wealthy people in Beverly Hills didn't feel safe while the riots were happening, so they ended up at the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel seeking comfort in numbers. The hotel stayed open very late and they wheeled in a TV so that everyone could watch the riots unfold, with drinks in hand. What a scene that must have been! I love writing books that take place in a pressure cooker, so I thought that would be a really fun setup for a novel.

You’ve been described as a method writer. Can you tell me more about that?

I went and stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel to do research for The Pink Hotel. I did a lot of research, actually. I did everything from reading architectural magazines to following the rich and famous on Instagram. I also did a lot of research on fancy dress balls. Truman Capote had a black and white ball in the '60s, while the Vanderbilts had a huge masquerade ball in the 1880s. Outrageous things happened at both of those parties, which got me thinking.

I didn't throw my own party, but I stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel and refused to leave for a week. I didn't want to go out and do anything touristy. People who stay at the Beverly Hills Hotel go there to experience the grounds and be secluded from the rest of the world, so I wanted to know what that was like. I wanted to see how long it would take me to acclimate to the climate there. It's surprising, but within three days, a $44 salad sounds very reasonable all of a sudden, and the outside world starts to disappear.

This was in February 2020, about a month before the whole country shut down due to Covid. All of that news just stopped filtering into my world. I wasn't checking my social media so much. I wasn't keeping up on the news. I was all about waking up in the morning, going swimming, having breakfast or lunch, wandering around the hotel grounds, and meeting people. I experienced what it would be like to be there for an entire week, just like Kit and Keith. It was very surreal. When I left, I felt like I’d been in a coma for a week.

One of the most vividly realized parts of the novel is what it's like to work behind the bar or in the kitchen. How did you get inside those jobs and bring them to life?

I've worked a tremendous amount of different jobs in hospitality. One of my first jobs was working at the Sherbourne Country Club, which is a very secluded club in Hidden Valley, full of influential people. That was my first brush with very wealthy people and their expectations for staff. You're more than staff—you're a friend or a confidante, but there's definitely a line when there needs to be a line. My husband was a longtime waiter at Pizzeria Mozza; he has PTSD-style dreams where he realizes, "There aren’t enough waiters tonight." I totally feel the trauma that goes along with being a server.

There are such powerful moments in the story when the wealthy guests tell Coco that she’s family, but Coco knows that she’s really not.

It’s not just about being family. They want her around—I can say this from my own experience. One of the things I heard a lot when I stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel was, “Rich people are a world unto themselves.” It doesn't matter if they're American or European or something else—they exist in their own global elite. They really enjoy having working class people around so that they feel benevolent. But if you make them feel too much out of place, they're like, "No, you don't understand me. You're not a part of this world." Coco absolutely knows that she doesn't really belong here, but it's so seductive when people with power treat you like an equal, because you want it to be true.

I’m reminded of a moment in the novel when someone describes a friend of Marguerite as “another working class hero for her collection.” How were you thinking about that dynamic as you calibrated these relationships?

I thought a lot about my own experiences with people who are very wealthy, but also: someone like Marguerite is very young. What has she seen while she was growing up? How has she seen people be treated? In some ways you can almost forgive her for being who she is because of the world she's grown up in. But I wanted it to come across that no one in the book is innocent. They're all very complicit in what happens, and in the outrageous things that unfold in the chaos. It’s true that Marguerite uses her friends as working class people in her colored pencil kit, but I really wanted it to seem like she's a product of her environment.

What was your most memorable hotel stay?

It was at The Fifteen Keys in Rome. I was doing research for The Worst Kind of Want, which takes place in Rome. I had to reserve the cheapest, most inexpensive room they had because it cost so much to fly there from Los Angeles. When we checked in, they gave us their largest suite on the top floor—their very best room, called the Grey Room. I kept thinking, “I think they've made a mistake. Do they think I'm somebody else? What's going on?” They treated us like we were famous. It was really wild, but they were very kind. They had champagne for us when we walked in, too. It was one of the first experiences I’ve had where I thought, "Oh, okay. Hotels can be very personable and fun."

This reminds me of something Mr. Beaumont thinks to himself in the novel: “He likes how the hotel can take an average person and turn them into someone else.” What is it about hotels that's such a site of fantasy and transformation?

Part of it is the anonymous quality. You can walk into those doors and be anybody. There's another line in there from Ethan, who says something like, "The worse you dress, the richer people will think you are.” It’s true. When you walk into a hotel, people don't know where to place you, and it's all completely dictated by your attitude. The more a hotel treats you like you deserve the penthouse suite, the more you're like, "You know what? I will go out to an expensive dinner tonight because I'm being treated like somebody else." When people are on vacation, they indulge a different side of themselves.

I’m reminded of how Kit is so anxious about wearing the hotel robe throughout the grounds. I thought, "Oh, Kit! That's exactly what rich people do.”

They don't care at all. That’s one of the things that I find so fascinating about the Beverly Hills Hotel—there aren’t really any walls. There are no gates to keep people off the property. It's entirely an attitude—that you don't belong there—keeping people out. I enjoy going into any extravagant hotel and mustering up so much confidence that security doesn't ask me why I'm there. In downtown Los Angeles, I'd always swan into the Biltmore Hotel and beeline for the restroom.

Certainly you get to tell a different story about yourself when you stay at a hotel, but the novel is also interested in the fabrications we tell about our own lives. At one point, Kit reflects, "This is their story, and she can't shake the feeling that the more Keith tells it, the less it becomes hers." What was the story you were hoping to explore about marriage?

I really wanted to explore love in general, in all its many different types. In today’s chaotic world, I feel like we're constantly in free fall. When I wrote this book, everything felt like it was falling apart, yet somehow we're in a worse situation than when I was writing the book two years ago. I didn’t want to ask, “Is love worth fighting for?” but rather, “Why does anyone still believe in love?” People are still getting married. People are still reaching out for connection.

The book was always going to have wildfires and civil unrest. While I was working on the final draft, there were wildfires in Los Angeles and the Black Lives Matter protests were happening. Los Angeles had these curfews, where at night you could hear flash bangs in the distance. I looked over at my husband, whom I’ve been with for over twenty years, and I just thought, "This is why. It’s love despite the monster.” Despite human ugliness, we still want to seek out companionship. But what are people willing to sacrifice for that?

The end of the novel devolves into a fantasia of hedonism, with exotic cats running around the hotel and young women wrestling in an inflatable pool of crème anglaise. How did you dream up this excess? Much of it defies belief.

All of it is true, based on research about real events. At that Vanderbilt masquerade, they brought in palm trees and all different kinds of plants to make their grand hall look like an interior garden. I read somewhere [about an actress] that was raised with lions, and that was where I came up with the idea, "Oh, people could just have wild cats hanging around their house." Of course that happens. Quite often, you hear about that. As for the crème anglaise, I heard about a party in the Hollywood Hills with mud wrestling. All I did was up the ante.

I was in France a couple of weeks ago, and I went to tour Ephrussi de Rothschild's villa. She had a dog wedding and sent out 1500 embossed invitations. Millions of dollars were spent on an affair that happened in her gardens, where these two dogs were married. I thought about the dog luncheon in The Pink Hotel and thought, "Maybe mine should have been a wedding. What was I thinking? I didn't go big enough.”

I had to have a dark chuckle about what happens with the masks throughout the story. When handed a mask, one person says, "I give these a day. Ain't no way they're on brand." Did the real life mask wars seep into the story?

Yes. Masks entered the story because of the fires, then Covid happened. When New York Fashion Week was cancelled, Christian Siriano ended up doing his show in his backyard. That was the first time I saw couture face masks. I thought, "Of course this is where face masks are going to go." I just wrapped it all into that. For a moment, there were chain mail masks. I don't know if they're popular anymore, but for a minute, you could buy fancy masks at Nordstrom.

Once we peel away all these trappings of wealth and excess from the novel, it has quite a bleeding heart about the hospitality industry, in the very best way. What do you hope that people take away from this novel, in that respect?

When I went and stayed at the hotel, I had already written multiple drafts of the book. I usually do that—I'll write a draft, then go to where the story takes place to see how much it measures up and what else I can mine. When I went to the hotel, one of the things I realized was that I had not really done the hospitality workers justice. I hadn't fully fleshed them out. Even though I’ve worked in hotels and restaurants, I had forgotten how much pride goes into working at a place like the Beverly Hills Hotel. If you're going to work somewhere for twenty or forty years, or if your father worked there and you've been grandfathered in, there's a lot of pride in what you do. We get to be somebody else when we're staying at a hotel, but there's a lot of work that goes into making us feel that way. It's almost like an enormous magic trick, and everyone working at a hotel is involved in that. I want people to remember that when you go anywhere within the hospitality industry, it’s not just a façade. It’s a result of hard work by people who take pride in what they do.

Have you shared this book with anybody from the Beverly Hills Hotel?

My publisher had a lawyer vet it, and for a while they were asking, "Should we mention the Sultan of Brunei at the end, in the acknowledgements?” I joked that we should be so lucky for the Sultan of Brunei to sue us. He owns the hotel, of course. This is the other thing about the hospitality industry: it’s very complicated. The people who work there are not the people who make the money. As I wrote the book, I was conflicted about that. I didn't want to give the Sultan of Brunei any money, but I wanted to have the book take place at the hotel. The people who work there are lovely human beings. So I have not shown it to the workers I met at the Beverly Hills Hotel, though I do plan to go by and hand them a copy.

Now that you've written this book and spent so much time thinking about hotels, has it changed you as a traveler or hotel guest?

At this point, I'm almost always thinking in story mode. When I stay at a hotel, I wonder if the workers want to be there, or if they don't want to be there, and who owns the hotel. Is it a family-owned hotel, or is it a chain hotel? Where is my money going? This is becoming especially relevant as we're seeing more and more hotel conglomerates. It's never just a family hotel—it’s often that somebody else owns it. Ultimately, I’m trying to do more due diligence in terms of researching where I stay. I suppose that's just responsible consumerism, and we should all be doing it anyway, but that’s how I travel now.

You Might Also Like