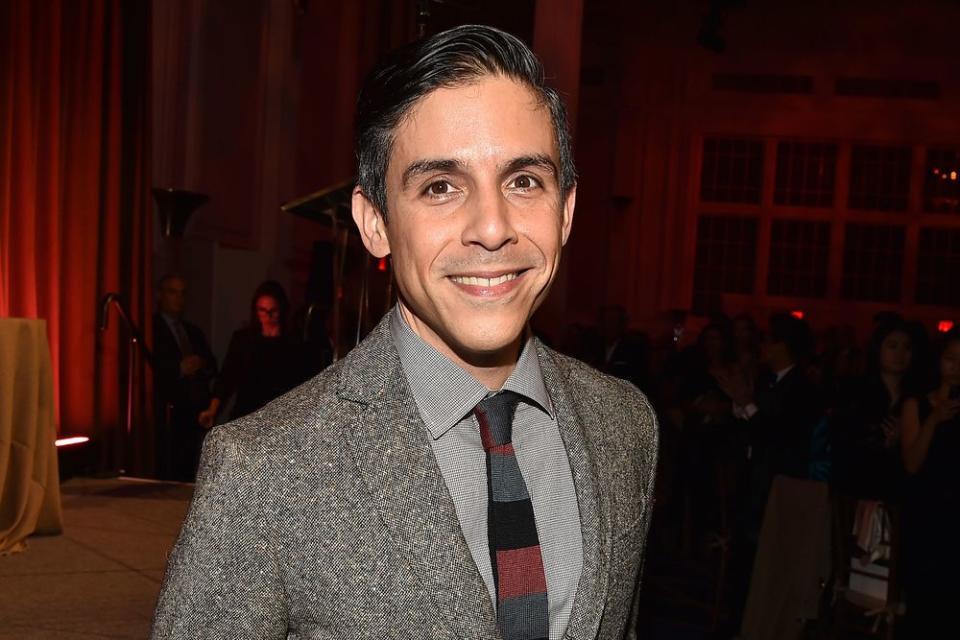

The Inheritance writer Matthew Lopez on crafting his supersized Broadway play

One of the most talked about (and Instagrammed) shows on Broadway this season is Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance. The epic, two-part play is a modern-day adaptation of E.M. Forster’s classic novel Howards End but told from the perspective of gay men in New York City. The show opened Sunday night on Broadway after a much-lauded run in London’s West End.

Over its nearly seven-hour running time, The Inheritance tackles everything from love to AIDS to loss to Broad City. It’s a hugely ambitious endeavor from Lopez and director Stephen Daldry (The Hours).

EW sat down with Lopez last week to talk about what inspired him to take on this classic work (hint: Entertainment Weekly was involved) and what he hopes people take from this emotional story.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: Where did The Inheritance come from?

MATTHEW LOPEZ: Well, it’s actually because of Entertainment Weekly. So I lived in Panama City, Florida, raised in panhandle Florida. My three big outlets were theater, books, and movies and what I relied on to know about anything was Entertainment Weekly. Entertainment Weekly was my outlet, and I remember reading an article about Emma Thompson, who no one had ever heard of over here at that time, and how she was getting Oscar buzz for Howards End. I think my memory has it that they were talking about how there’s nothing about her performance that’s just typical Oscar bait, it’s just a great performance. I wanted to see what that looked like and because I lived in a small town, I knew that I had a week and it’ll probably be gone. So I had my mom take me to see it. I was maybe 15 or 16 and she took me one Sunday after church. That Sunday my life changed as a result of watching that movie.

What was it about Howard’s End that resonated with you?

I think it was the foreignness of it was so appealing to me in some way. It was such a transporting experience. I doubt it was the first period piece I’ve seen, I was a teenager, but it was probably the first period piece that I saw that felt alive and present at the time that I saw it. Even though it was so steeped in its period, and because of course it was a Merchant Ivory film, period details were just sumptuous and perfect, it still felt contemporary. I really latched onto it and I really, really fell in love with the story and the characters. The characters most especially, I think. My mother was a teacher, and she went out and bought me the book, and I read the novel and fell in love with the novel. I fell in love with Forster.

It wasn’t until a lot later when I was in my 30s and I was rereading the book, I think what drew me to the story in the first place and what drew me to Forster in general was his queerness. His closeted queerness but that perspective on the world, especially at that time, that outsider’s perspective sort of living the life of that insider pretending to be an insider when he’s really an outsider And the way it caused him to view the world, It was so unique. I think I responded to that cause there was nothing about that story that really sort of spoke to a young Puerto Rican kid living in Florida, but I think it was sort of the queerness without being a queer book and then later finding out that he did write a queer bible [Maurice, which was published after Forster’s death] and that he lived his life in the closet. I felt a lot of empathy for him as a person. I felt protective of him as a reader, as a fan and I wanted to do something to honor that, what he gave me. That’s sort of where the idea came from to take my favorite novel by my favorite author and queer it.

Gay it up!

And gay it up. And the truth is that he stopped writing books early in life, and it was because he couldn’t write honestly. He couldn’t write truthfully. And he didn’t think he could write if he couldn’t write truthfully. I just sort of wanted to take one of his most beloved novels and f— with it.

Tell me about the way you decided to structure it with the main characters writing their story and having the ghost of E.M. Forster helping them. Did you always imagine Forster to be in the play?

I remember looking back at my early notes, and the idea of including him was always present. I think once I really got to know him in a granular way because before I started writing this, I started to do a lot of research into his life and reading biographies. He felt so alive to me. He felt so like he deserved to be in this play. It could not just be a straight-forward…I wanted to acknowledge in the writing and in the presentation of the play what we’re engaged in. I didn’t want to sort of create a false film over the play that denies that it’s based on a novel.

I wanted to create an actual frame around the play that not just acknowledges that this is based on a book, but that the characters in the play, know of the book and that the book exists in the world that they exist in, that E.M. Forster existed as a person. I wanted to include Howards End as a truth in the world as I’m doing my adaptation of Howards End.

So the idea of the frame that we use in the play of the young men trying to tell their story and summoning the spirit of E.M. Forster to help them, really does largely reflect how I came to writing this play. The frame of the play is about the writing of the play. We avoided at all costs getting too cleverly meta about it. I think of Charlie Kaufman’s script for Adaptation. In part, what the play is about is the creation of the play itself.

You write a great deal about the lost generation—the men who died of AIDS in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Do you have touchstones from that age group that helped you with those portions?

One of the reasons I wrote the play is because I did not feel like I had touchstones with that generation. I didn’t have relationships with them and if I’m being honest, I largely found that generation, for the longest time, to be very unknowable and opaque to me. Even more honest, I would say as a young gay man of color, my relationship to older white gay men was really not good. I found I had no compassion for them, and I felt they had no desire to understand me, not just as a younger gay man but as a younger gay man of color. I wanted to understand them, I really wanted to. It grieved me because there was, in my life at least, this divide between us.

In part what I wanted to do was just understand the generation. I [wanted that] as a young queer Puerto Rican, and I wanted to understand older gay white men in particular because, well, I married a white man, so I really wanted to understand that generation. What I didn’t want to do was just sit down and interview people and research because that could yield a lot of dry writing. So the only thing I did, the only real way to create compassion, is to put myself in their shoes. I said, “What would I have done in this situation? What would my reaction be? What would my friend’s reaction be?” The scene at the end of Act One when Walter asks Eric to imagine this happening to his friends is something that I had to force myself to do.

What you learn when you attempt to understand other people, the differences that seem to be between you that divide you, are not as great as you think they are, and once you attempt to just understand someone else, walk in their shoes for a bit, you can write very compassionately. You can hopefully write honestly about them without having had lived their life as well. I hope in return, I’ve explained my generation to the older generation a little better and in the relationships that I’ve forged is a result of working on the play. Stephen Daldry, the director of the play, is a gay man of that generation. And then a lot of younger gay men in the company who are of the younger generation from me, I’ve forged relationships with them. The play has allowed me a broader understanding of the community that I belonged to. It has expanded my definition of what that community looks like. It’s given me a real sense of belonging when I felt a real sense of alienation.

The play is told in two parts. Did you ever consider cutting it purely from a marketability perspective?

Yeah, sure. I was told, “Don’t make it two parts. Do it in four hours if you have to. Don’t do it in six and a half.” No. My attitude is always like, you’re under no obligation to produce this. If this never gets done then so be it. What I don’t want to do is present something that doesn’t resemble my intention.

The staging is very sparse and is basically just one big table. Did you write it like that? Or is that something Stephen came up with?

It was the first play I ever wrote, not really knowing how it might be staged. Normally, I think it’s in the best interest of any young playwright to sort of have the answer to how do you stage this. It was the first time I ever just decided not to worry about that and just write the thing I wanted to write and let that be the director’s worry. When Stephen and I started working on this, we did our first workshop, and what you see in the production was in many ways there in the first workshop. He set up a big rectangle of tables and he put all the actors on the outside of the rectangles sitting in chairs, and then he used the space in the middle to stage scenes, which is essentially what we do in the play.

Stephen drew his staging ideas, helped me really harness the play once it had been written and really make it producible and directable. From that moment on, Stephen and I worked hand in hand to make this thing what it is. His staging has been very influential on the further development of the play.

Since this is a play about what it means to be a gay man, do you prioritize casting gay actors or the best person for the job?

I have to go for whoever’s right for the role. The play is too enormous. The roles are too enormous to not do that. I’m very sensitive to the feelings of out gay actors in this business who see roles going to straight actors. As we were casting, we made a lot of overtures to out gay actors, many of whom passed on these roles. So, I’ve learned you cannot force an actor to do a play at gunpoint. We opened the doors to all corners and we looked at who was best for the part in terms of their spirit, in terms of their voices, and we cast the show according to those needs.

Before Broadway, the play was staged in London. Did you make significant changes before you brought it to New York?

There’s two types of changes that were made. One was simply we hadn’t gotten everything right, so a lot of the work that we did was getting it right. Part 1 is very clean and simple and spare — there’s an elegance and a simplicity to the staging that reflects the simplicity of the storytelling. Then in Part 2, the story gets messy and it’s consciously messy because their lives get messy. But it also means that the storytelling is harder to block. We spent a lot of time from the Young Vic to the West End and from the West End to Broadway, honing and refining and clarifying the story of Part 2.

The other thing that we wanted to do when we moved to New York is really put in references that a New York audience would get. There were things that we reserved that we took out in London because we knew a London audience wouldn’t respond to them. When they list the gay bars that have closed in New York City, London audiences aren’t going to get that and there’s nothing worse than throwing things out in front of an audience and have it be received with silence.

Henry Wilcox, played by John Benjamin Hickey, is the only name from the book that you carried over. Why is that?

Good name. I couldn’t best it. It sounds so Republican. Don’t mess with perfection.

Speaking of Republicans, the play deals with the 2016 election. We’re on the cusp of a new election — do you imagine you’ll update the play at all?

No, because the play is set in his very specific timeline. The play starts in 2015. I did have to go back and rewrite the play. Well, what happened was I had the play written and then Trump won. I had a talk with Stephen shortly thereafter, and we were like, we can’t ignore this. You cannot write a play about history and then have it be a historical when it comes to what America is going through in the present moment. So I had this play all done, “done” in air-quotes, and then I had to go back and write the whole thing again.

There are also a lot of current pop culture references. Do you think you’ll update those?

No, I think the play is going to be what it is. I think the play is not going to move with any further time. The play has to live in the time that it was set, and that needs to be a snapshot, which I know it means that the play will start to age over the decades if I’m lucky enough to have it be remembered in decades time. But that’s okay because the play is so much about the continuum of history, I’m not worried about the play aging out.

I think that because the play also speaks so much to things that don’t require a timeline to understand. What is our responsibility from one generation to another? What are our responsibilities to others in our community, not just in the queer community, but as Americans? This play is about the gay experience specifically nestled within the queer experience universally. But beyond that, it’s also I hope very relatable universally. A lot of our audience is straight and there are themes in the play about the responsibility to each other as Americans. I look at the response to the AIDS epidemic in the ’80s and the ’90s. It was a community response. That was individual citizens banding together to affect change in the world, and that is an example to us in the age of Trump. If you want a lesson on how to respond to the election of Donald Trump, you need to look no further than the actions of the activists in the ’80s and ’90s.

The man I sat next to had seen the show three times. You have such fervent fans and people react so emotionally to this. What kind of fan encounters do you have with people?

I realized early on, once we realized what this play could do to an audience, I quickly learned at the Young Vic, because you leave the theater at the Young Vic and you go right into the bar. There’s a restaurant in the bar and everybody just hangs out there. It’s inescapable that you will encounter people who have just seen the play and I realized very quickly that my job after the play is over, after having them listen to my story for six and a half hours, is to listen to theirs in return — and they’re so willing and desiring to tell their stories after seeing this play. It’s very humbling and it’s very moving. You can ask any actors in the play too, I have held so many strangers as they’ve cried for the last two years of my life. Just the other night in front of the theater, a young man came to me and started crying and I stood on the sidewalk with him and two of the other actors and we just listened to him tell us his story. It’s a responsibility and I love that the actors also take it very seriously. They don’t take it for granted. It’s been like I wrote this play in part because I felt alone in the world and it has cured me of that feeling.

Have you been approached for this to be turned into a limited series? Is that something you’d want to do?

Yeah, of course I would love to do that. I’d love to get this play open first and then I’d like to take vacation and then I’d like to work on other things. It’s definitely a very compelling idea. In an effort to make sure that the play isn’t longer than it needs to be, we’ve cut so many things out of the play that we love. So many scenes that we love dearly that we cut, that might find another life in a limited series. But that’s further down the road and we’re not really seriously thinking about that right now.

What do you think about being compared to Angels in America?

Obviously it’s flattering. Being a young man in college in the 1990s, Angels in America was inescapable, especially for a theater student. I studied it in every class so it is the seminal piece of dramatic writing for my generation in our formative years. That said, they are very different plays.

I think the comparisons ultimately are superficial. It’s in response basically to run time and structure more than anything else. I wasn’t chasing after Angels in America. What I certainly wasn’t doing when I sat down to write this was, let me write the next Angels in America. I don’t like that comparison in that I’d like to be the first Inheritance. Angels in America wasn’t the next whatever.

I wouldn’t be the writer that I am if it weren’t for that play and for the work of Tony Kushner and I don’t know a single theater artists my age who would say differently. The debt that I have to him and the debt I have to that play is immeasurable. But I’m writing my own story.

What do you hope audiences take from watching The Inheritance?

I hope that this play gives audiences what it’s given me, which is a sense of belonging to something larger than myself. I think we live in an age because of social media, because of such fractured lives that we lead, it’s really hard to feel connected to something, and the connections that we do have seem to always be an opposition to things. We seem to be more connected these days by what we dislike than what really moves us and what we really feel we belong to. I hope this play allows people to feel a part of something, even if it is simply a part of the human story that we’re telling.

I was never ever trying to speak for a community. I was never ever trying to speak even for other gay men. I was simply attempting through investigating my favorite novel, to tell my story of my life. But more importantly, I just wanted to write something that was deeply personal and hope that it would have universal applications and what we’re discovering is that it does and that people see themselves in the play.

—The Inheritance is a funny, tender marathon drama

—In Broadway’s For The Girls, Kristin Chenoweth is center stage — but she lets everyone shine

—A hectic, music-packed Tina: The Tina Turner Musical brings electricity to Broadway, not subtlety