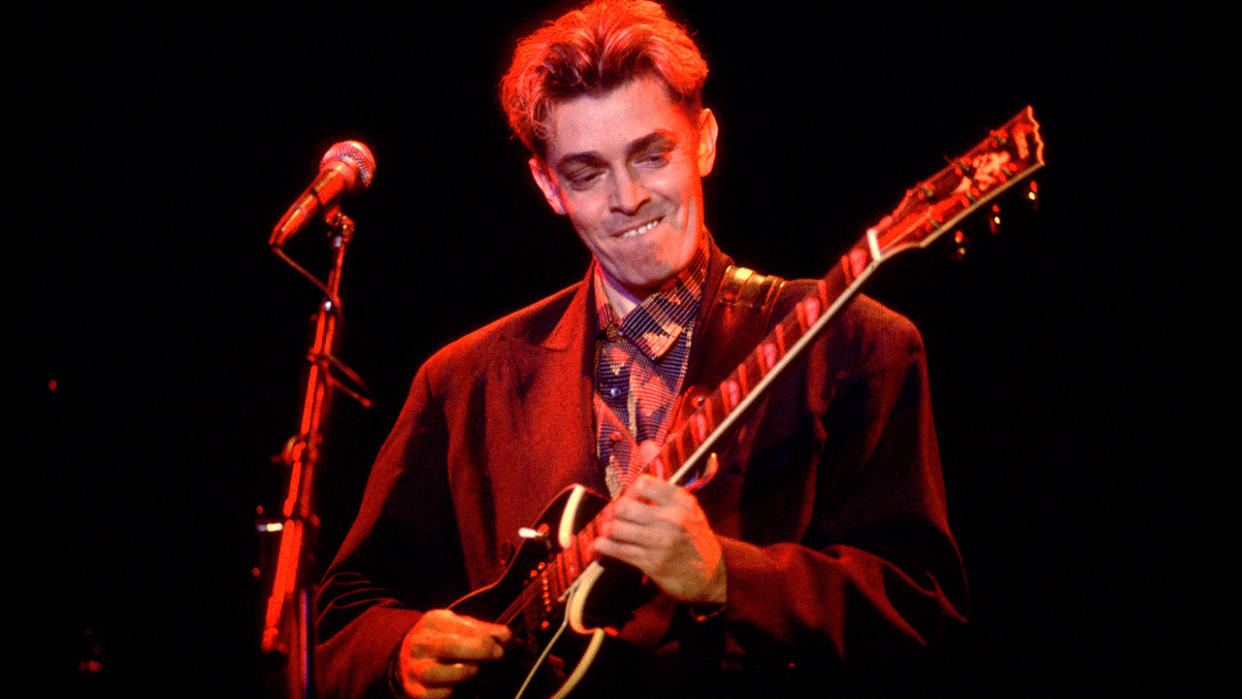

“It should be illegal to be in a band, and only those willing to be arrested and locked up should try and pursue music”: Bill Nelson was only partly joking with his pre-punk manifesto

In 2011 Bill Nelson had a total of 20 albums due to for launch, consisting of a five-record set of Be-Bop Deluxe material, and eight-disc collection of solo work and six completely new solo releases, which he’d produced, arranged and mixed in his Yorkshire home studio. He found time to talk to Prog about his work ethic and future plans.

Bill Nelson is surely one of only a few musicians ever to appear in Prog to have recorded upwards of 90 albums in total, which he records these days at the rate of between four and six a year. The question is, what do you call this almost ludicrously prolific recording artist and who has recorded in virtually every style in the modern music canon – from pop and rock to new wave, ambient and electronica – composed soundtracks and even made forays into painting and photography?

How about ‘maverick’? He considers this description. “Well,” he says with a wry chuckle, “I guess that’s not too far off the mark.”

In the late 60s, Nelson attended Wakefield Art College, staged multimedia happenings and played in a variety of bands with names like Purple Tangerine Snowflake. Officially his career began in 1971 with the solo album Northern Dream, whose meditative ballads and folky, bluesy rock reflected the hippie era and his adoption of fundamentalist beliefs after marrying a Pentecostal Christian and taking up with the Gentle Revolution church group.

“I was involved in a search for meaning,” he says, describing himself at the time as a psychedelic troubadour. “A spiritual search. Everyone wants to discover the meaning of life, don’t they?” This, he explains, has been a constant of his work, whatever the stylistic detours he might have made over the past decades. “If you understand your life, you’ve got a better chance of integrating with others. ‘Know thyself,’ as they say.”

Northern Dream drew the attention of a certain John Peel, which in turn led to a deal with EMI for the band of jazz-tinged art-glam-prog gypsies Nelson had gathered around him and decided to christen Be-Bop Deluxe. “A lot of people didn’t get what we were doing at the time, in the same way that they didn’t get Red Noise because they found it too jagged and abrasive,” he smiles, recalling his late-70s post-Be-Bop venture. “But they do now; now it clicks.”

Maybe the problem with B-BD, who he admits he formed “as a way of getting up the noses of people in the working men’s clubs and pubs of Yorkshire in our theatrical glam rags,” was that they were just too hard to categorise.

“We covered so many different styles in so many subtle ways,” he agrees. “I grew up listening to lots of different types of music, not just rock, from 40s swing and 50s modern jazz to classical and folk. I love music full stop and don’t build barriers. I fight against that and encourage my fans to do the same.”

Still, a couple of genre tags don’t offend too much. “‘Art rock’ would fit to some degree,” he decides. “And ‘postmodern pop’.” In their complexity, did Be-Bop have anything in common with the prog brigade? “The Futurama album [1975] definitely did,” he replies. “That had some quite elaborate arrangements.” The difference between B-BD and the prog bands was, he says, largely conceptual.

“It’s a bit of a generalisation, maybe, but they were kind of neo-classical and Tolkienesque, whereas I was always more into pop culture: Lichtenstein, Warhol, Peter Blake, those sorts of influences. On Sunburst Finish [1976] there were quotes from Duane Eddy as well as from pantomime Chinese music. I’d plant all these little clues, nods and winks so that someone into this plethora of pop culture references would recognise them and get the sense of play.”

More than anyone in either the prog or glam camps, Nelson would place Be-Bop alongside those other exponents of reference-heavy postmodern pop, Roxy Music, 10cc and Sparks. “That was my territory. Like those bands, I absorbed everything around me.”

Not that he ever felt he really belonged in any camp. B-BD toured with Cockney Rebel, but Nelson never socialised with Steve Harley any more than he did with Messrs Bowie or Ferry. He even wrote a song for Sunburst Finish called Fair Exchange about “the artificial experience of being in a band, the temptations of the music industry which I was never comfortable with, and the phonies...”

There were some rock star indulgences, including a Rolls-Royce and a Porsche, that were “a bit of fun – I came from a working-class background where those things were complete fantasy, and I was young, so I kind of went for it briefly.” But in a sense he was a performer out of time – or rather, ahead of his time.

“I had a letter published in the NME in 1974,” he recalls, “saying that the music industry was basically a dinosaur, bands were out of touch, and it was time to move on. It was like a manifesto, and it predated punk by two years. So when punk came along I laughed. I meant to stir things up, because I was frustrated with the pace of the industry and I felt there were too many bands playing very poor music without any sense of adventure.”

I was frustrated with the pace of the industry and I felt there were too many bands playing very poor music without any sense of adventure

Nelson’s proposal to the weekly music paper was that “it should be illegal to be in a band, and only those willing to be arrested and locked up should try and pursue music.” He laughs when he looks back at this now. “It was partly a joke, but partly a challenge, because everything had become too easy and complacent. It needed more danger, and a greater sense of commitment.”

How did he feel when punk came along in 1976, with its anyone-can-do-it credo? “I thought it was okay up to a point, but I also believed someone should have been given the job of weeding out the rubbish being made made by people who clearly shouldn’t be doing it.”

In fact, in 1977 the NME invited Nelson to pen a follow-up article once punk had taken hold. In it, he asserted that Be-Bop Deluxe were in some ways more radical than the Sex Pistols. “I made the point that if you took a Be-Bop Deluxe record and played it to a grandfather and then did the same with the Sex Pistols, he would enjoy and understand the Pistols one but think the Be-Bop one was impenetrable,” he recalls. “Because the Pistols were really just hyped-up 50s rock’n’roll. They were incredibly retrogressive, although Steve Jones [Pistols guitarist] was apparently a huge Be-Bop Deluxe fan!”

Nelson was equally sceptical in the period after punk when bands started incorporating electronic music elements into their work. “I was never a fan of The Human League – I was listening to Kraftwerk in the early 70s, before they had hits, and to people like Terry Riley, Stockhausen and John Cage. At art college I’d been involved in electronic tape manipulation for theatre companies, so I thought the post-punk electronica crowd were a little late!”

At art college I’d been involved in electronic tape manipulation for theatre companies, so I thought the post-punk electronica crowd were a little late!

Be-Bop, too, he argues, were ahead of their time in the proto-electronica stakes. “I remember getting a second-hand mini-Moog, the first seriously affordable synth, when we were recording Drastic Plastic [1978]. I used it on the track Electrical Language. And we were doing drum loops. Even on Modern Music [1977] we were doing cut-ups. We were there first.”

Sound-On-Sound, the album he made in 1979 as Bill Nelson’s Red Noise – following Be-Bop’s dissolution – was arguably his first that chimed with the times, featuring the jerky new-wave pop of XTC and the corrosive, cerebral post-punk of Magazine.

“That period is when things started opening up,” he say. “Punk saw a narrowing down, but at the turn of the decade I felt more encouraged, and I got asked to collaborate with a lot of those people.”

By the early 80s he’d produced Days In Europa for Skids and collaborated with everyone from David Sylvian of Japan to Yellow Magic Orchestra. He had also become, in the famous words of King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, a “small, mobile, intelligent unit,” a solo synth-pop artist in the manner of John Foxx and Gary Numan.

He even had a near-hit single in 1981: Do You Dream In Colour? which, although stalling at number 52, gave Nelson his biggest mainstream exposure since Be-Bop Deluxe had appeared on Top Of The Pops five years earlier with Ships In The Night.

Many fans were dismayed at his apparent abandonment of the electric guitar in favour of the synthesizer. “It wasn’t as though I thought, ‘Here’s an opportunity to make some money: stop playing guitar and play electronic music.’ I’d just got absolutely bored with playing guitar! There were so many players. It had lost its power.”

I’d just got absolutely bored with playing guitar! There were so many players. It had lost its power

Of course, since then, diehards have had to get used to his numerous changes of direction. They’re a fanatical bunch, a small yet devoted cult who monitor his every move, even holding an annual convention called Nelsonica (although the less said about his stalkers – “I had to get a court order against one who proved to be dangerous” – the better).

They have followed him through the lean years, notably the late 80s and early 90s when he had marriage and financial problems and endured “a lot of dark times when I had to sell my guitars to survive.”

There have been digressions – not just musical but spiritual: Nelson has, over the years, embraced Christianity, Gnosticism and Rosicrucianism; he even had a temple in his loft at one point where recruits would come to pray. These days he’s a Buddhist. “I’m the laziest Buddhist in the world,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t exactly sit there and meditate. Making music is meditation for me.”

If he’s lazy in his religious practice, he’s a workaholic in the studio. This year he released Fantasmatron, which be followed by an album of improvisational guitar work, a pastoral symphonic suite, an album of neo-psychedelic pop songs, a collaboration with American comic book artist Matt Howarth called Last Of The Neon Cynics, and another titled Songs Of The Blossom Tree Optimists.

“Oh,” he suddenly remembers, “and I’ve got one that’s not finished that I’m going to call Joy Through Amplification that will be vocal-led, with hard-edged percussion and processed guitars, quite stripped back and raw, because a lot of the stuff I’ve been doing recently has been fairly lush and rich.”

It’s all over the place, and that over-the-placeness can happen in one song! I can’t describe my own stuff

The process of doing album after album can, he says, be “physically demanding,” but he never worries about running out of ideas. Is he concerned that, through this system of patronage, the fans who literally support him will be put off by his more esoteric ventures? “No,” he decides, “because they know by now to expect the unexpected.”

Which brings us back to the start, and the impossibility of pigeonholing Bill Nelson. “It’s all over the place,” he says of his massive back catalogue. “And that over-the-placeness can happen in one song! It might be a quiet, melodic ballad with digital distress in the background. I can’t describe my own stuff.”

Besides, Nelson doesn’t get like to get too bogged down in classification – he’s too busy with his numerous ongoing projects. “Once an album is finished I move on,” he says. “I’m always looking for the next thrill. It’s chasing comets, really. But I’ve still got so many ideas, and I’m still not remotely at the point where I can say: ‘I’m done.’ I’m nowhere hitting that satisfaction button.”