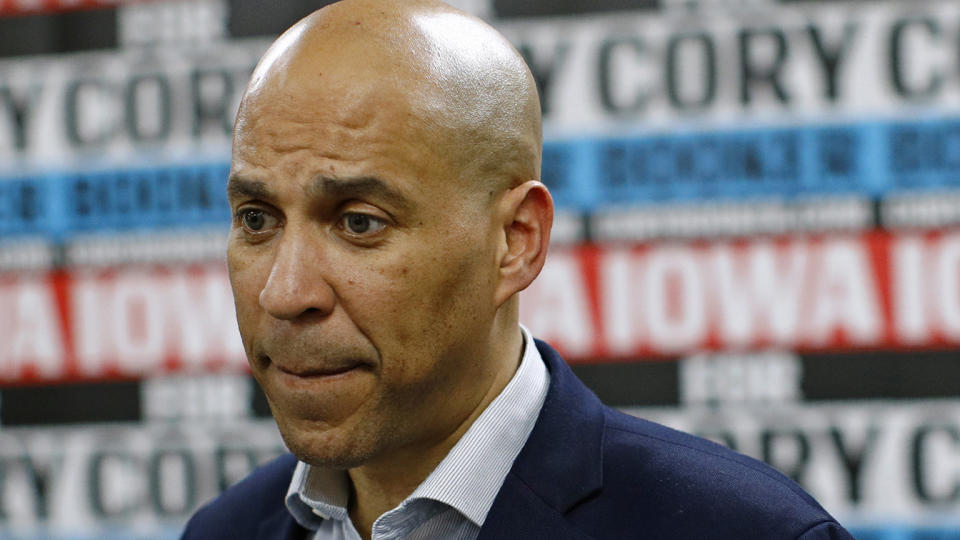

How race hurt Cory Booker — and the rest of 2020's diverse field

Welcome to 2020 Vision, the Yahoo News column covering the presidential race with one key takeaway every weekday and a wrap-up each weekend. Reminder: There are 21 days until the Iowa caucuses and 295 days until the 2020 election.

And then there were … none.

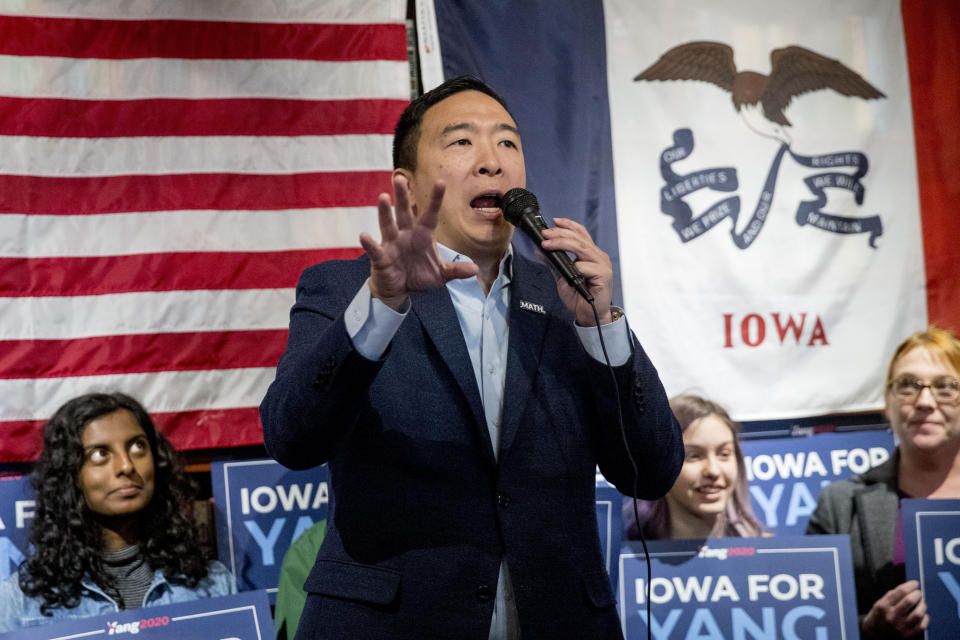

On Monday, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker announced that he was suspending his campaign for president; last week, the Democratic National Committee announced that not one of the party’s remaining candidates of color had qualified for the opening debate of 2020, to be held this Tuesday in Des Moines, Iowa. Not businessman Andrew Yang. Not Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard. Not former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick.

As a result, there is now virtually no chance the Democratic nominee will be a person of color — something considered plausible, indeed likely, at the start of a contest with a historically diverse lineup that came to include multiple black contenders and the first major Latino and Asian-American candidates in U.S. history.

The question that Democrats are asking now, on the eve of the first all-white debate of the cycle, is why? Why did two high-profile black senators (Booker and California Sen. Kamala Harris) drop out before Iowa? Why didn’t Julián Castro, America’s most prominent Latino politician, ever crack 2 percent in the national polls? Why are all four of the remaining front-runners — Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg — white?

Is race the reason? The answer is complicated. But the available data suggest that yes, race had a lot to do with it.

The first thing to note is that candidates of color faced an uphill climb from the beginning. This is partly because of the “electability” factor — the idea that Democratic voters, nervous after fielding a losing female nominee in 2016 and obsessed with finding a standard-bearer who will beat Donald Trump, were worried that other voters might shy away from a candidate of color.

The more fundamental problem was that representation wasn’t enough. It never is. Voters of color are sick of being used as props, and they tend to respond, regardless of race, to candidates who show up early and often, tailoring their campaigns to the community’s specific needs. This isn’t a secret: Black voters warned as much after the last presidential election. In a November 2016 interview with the New York Times, some black voters from Wisconsin, perhaps the key swing state, said they decided to stay home on Election Day because both Clinton and Trump struck them as all talk and no action. Trump wound up winning the state by 23,000 votes after the black turnout rate dropped from 79 percent in 2012 to 47 percent in 2016, the lowest in the state’s recorded history.

“Milwaukee is tired,” said barber Cedric Fleming. “Both of them were terrible. They never do anything for us anyway.”

This time around, two well-known candidates managed to make early inroads with the all-important black electorate: Biden with older black voters and Sanders with younger black voters. In fact, a new Washington Post-Ipsos poll shows that these two septuagenarian white men command support from 68 percent of black Democratic voters, who made up 24 percent of the primary electorate in 2016 and likely more in 2020. Biden leads with 48 percent overall; Sanders leads 42 percent to 30 percent among black Democrats ages 18 to 34. Their near-universal name recognition and ideological clarity gave them an immediate leg up with key black constituencies, and that made life a lot harder for Booker, Harris and others. Building a base by appealing to black voters is one thing; building a base by peeling off black voters from candidates they’ve already liked for years is another.

An overcrowded field further complicated matters. In October 2007, Hillary Clinton led Barack Obama by 24 points among black voters; after Obama won Iowa the following January, the black vote shifted to him by a wide margin. Experts have long attributed that shift to Obama’s success in dispelling doubts in the African-American community that he could win in largely white states.

Yet by January 2008, Obama was Clinton’s only real competitor. This cycle, there were literally dozens of candidates competing for the anti-Biden mantle, and thus no single, obvious rival for the support of voters of color. That’s part of the reason Biden’s stumbles on race never seemed to affect his poll numbers. With several rivals dividing the rest of the Democratic pie — and never really cracking five percent because of it — no one else ever looked particularly viable. It wasn’t clear where else voters of color should go.

The rules didn’t help. To qualify for the debates, candidates had to clear specific polling thresholds, either nationally or in the early-voting states. This created two problems. First, it’s usually more difficult to get accurate polling results from underrepresented communities, for a host of reasons; second, the first two states to vote are the sixth whitest (Iowa) and fourth whitest (New Hampshire) in the union. These challenges may have contributed to a vicious cycle of sorts. Candidates of color initially polled lower than more familiar faces, especially in Iowa and New Hampshire. Voters saw those surveys and started to doubt whether candidates of color could win, further suppressing their poll numbers. Candidates of color then failed to qualify for subsequent debates. Lacking visibility, they never quite recovered.

The Democratic National Committee maintains that the rules, which took into account both state and national polls, gave every contender a fair shot.

“We’ve been as inclusive as possible to allow as many people as possible to have that debate stage and speak their message,” said DNC communications director Xochitl Hinojosa in an interview with Yahoo News before December’s debate, the first to feature no black candidates.

Some candidates of color are not convinced. Yang, who is currently polling at 4 percent nationally and may be trending upward in Iowa, recently described the small number of qualifying polls as a barrier to “a diverse set of candidates” and pleaded for more, according to a leaked memo sent to DNC chair Tom Perez. The DNC did not budge.

Finally, it’s worth considering whether the political media ever really treated Booker, Harris and Castro the same as, say, Buttigieg, the only low-profile candidate who did manage to break through. Part of Buttigieg’s success was the element of surprise: the way a 37-year-old gay mayor of Indiana’s fourth-largest city seemed to come out of nowhere and, sterling résumé in hand, sound like a plausible president.

Yet Booker was also a youngish former Rhodes scholar, who once ran a city nearly triple the size of South Bend and often earned strong reviews from viewers for his eloquent debate performances. Why didn’t he have a moment? Was it because “he’d had so many moments before,” appearing “on magazine covers and [as] the subject of glowing profiles since the mid-2000s,” as New York magazine’s Olivia Nuzzi argued on Twitter? Was it because “the media regarded him as though they (we) had been there and done that already,” so he could never be “the shiny, new thing like Pete Buttigieg?” Or, like other black Americans, did Booker also have to work twice as hard to get half as far?

These aren’t either/or propositions. They’re both/and. And so Tuesday’s all-white debate stage will serve as a reminder of the role race still plays in American politics. Did Booker, Harris and Castro fail to catch fire simply because they were candidates of color? No. Is that the only reason Yang, Gabbard and Patrick won’t be debating in Des Moines? Hardly. But even in a party that nominated the man who went on to become America’s first black president — a party that prides itself on its plans to combat systemic racism — the color of their skin didn’t help. Quite the opposite.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Did the U.S. 'assassinate' Iranian general or just kill him? Why it matters

Saudis warn of new destructive cyberattack that experts tie to Iran

Your Democratic primary cheat sheet: In the run-up to Iowa, who's still in the race?

PHOTOS: Ukraine International Airlines plane crashes in Iran killing all on board