'Honest' Farmer Remembered for Saving Crops of Japanese-Americans Sent to WWII Internment Camps

The 78th anniversary of a dark chapter in American history is being remembered on Wednesday.

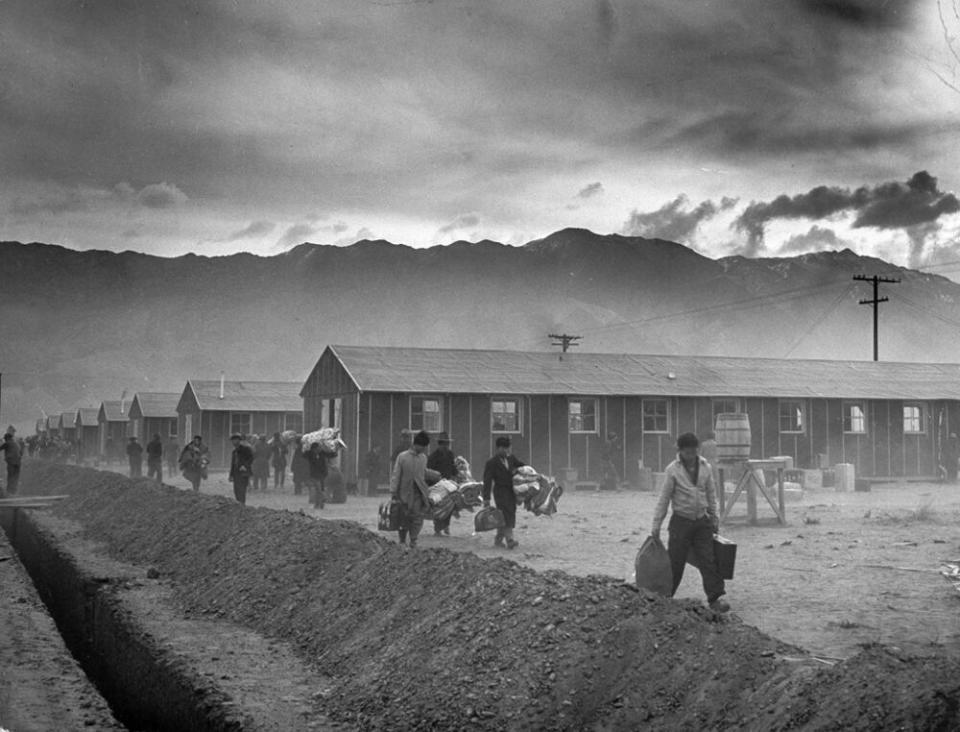

On Feb. 19, 1942 — two months after the U.S. entered World War II following the attacks on Pearl Harbor by Japan — President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which gave the military power to identify civilians they considered a security threat and imprison them in internment camps along the country.

This resulted in nearly 120,000 people of Japanese descent, many of them American citizens, being forcibly removed from their homes and jobs and incarcerated in 10 barbed-wire camps throughout California, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Arkansas and Idaho.

While Roosevelt’s order was largely initiated by fears of sabotage and spying, paranoia and racism also played a central part.

“They are a dangerous element, whether loyal or not,” John DeWitt, Army commanding general of the Western Defense Command, said at the time of people with Japanese backgrounds.

“I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp,” echoed Colonel Karl Bendetsen, then the Administrator of Wartime Civil Control Administration.

RELATED: Pediatricians Release Heartbreaking Drawings by Migrant Children While in Border Protection Custody

Thousands of Japanese Americans were sent to these camps as racial tensions permeated throughout the country. But Sacramento farmer Bob Fletcher did not give in to anti-Japanese sentiment, and instead came to the aid of his neighbors when they were forced from their homes.

According to the Washington Post, Fletcher quit his job as a state agricultural inspector and worked to save the nearby farms of his neighbors: the Nitta, Okamoto and Tsukamoto families.

Though Fletcher was taunted as a “Jap lover” and was nearly shot by a bullet that was fired into a barn, he endured through the criticism and paid the mortgages and taxes of the farms as he awaited the families’ return — whenever that would be.

RELATED: George Takei Powerfully Compares Immigration Crisis to His Time in a Japanese Internment Camp

For his efforts, Fletcher — who tended to a total of 90 acres over three farms — only took half of the profits from the crops, and turned over the rest when the families returned home three years later in 1945.

“I did know a few of them pretty well and never agreed with the evacuation,” Fletcher told the Sacramento Bee in 2010, according to the Los Angeles Times. “They were the same as anybody else. It was obvious they had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor.”

Fletcher — along with his wife of 67 years, Teresa — lived in the Sacramento area until his death on May 23, 2013. He was 101.

“He saved us,” Doris Taketa, who was 12 when Fletcher took over her family’s farm, told the New York Times.

“Few people in history exemplify the best ideals the way that Bob did,” added Marielle Tsukamoto, who was 5 when her family was interned, to the L.A. Times. “He was honest and hardworking and had integrity. Whenever you asked him about it, he just said, ‘It was the right thing to do.’ “

President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties act in 1988, which acknowledged the injustice experienced by Japanese-Americans who were relocated to the internment camps. The bill also paid out $20,000 in compensation to each surviving victim.

RELATED VIDEO: U.S. Agents Spray Migrants with Tear Gas Before Trump Threatens to Close Border ‘Permanently’

This week, California is expected to pass a resolution to offer a formal apology for its part in the internment camps.

“It’s nice, okay, but it was almost 80 years ago and most of us that were there are dead,” Paul Tomita, who was about 3 years old when his family was placed in an internment camp, told the New York Times of the pending resolution.

“Those that were really affected,” he added, “like my grandparents and parents who lost everything, their businesses, their houses, everything — they’re dead.”