How Hollywood Tried To Smash The Patriarchy in 2023

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

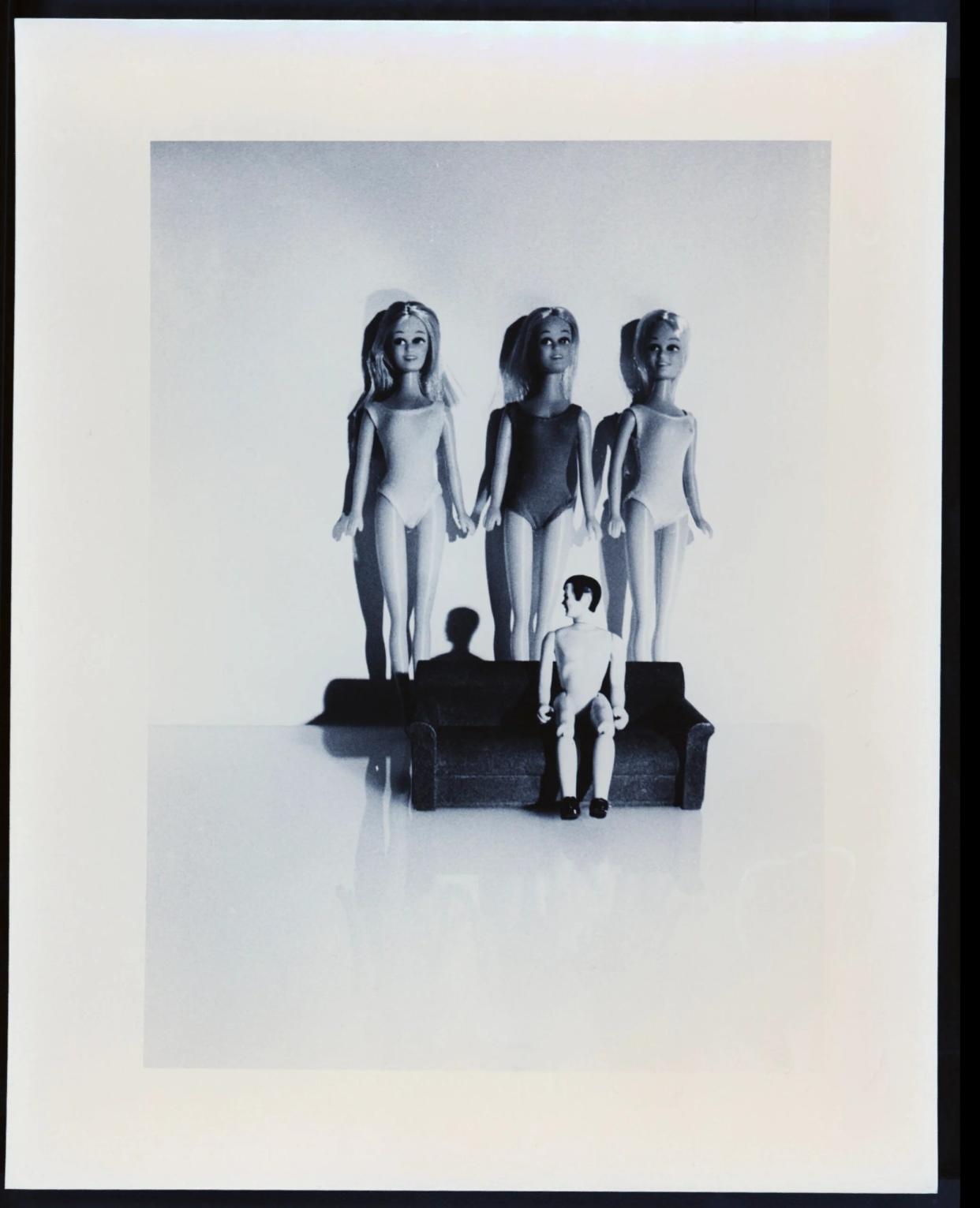

Artwork by Laurie Simmons

By Salamishah Tillet

By giving voice to the cognitive dissonance required to

be a woman under the patriarchy, you’ve robbed it of its power.”Stereotypical Barbie (2023)

As a little girl, I hated dolls. Fashioning myself as a partial nerd, I’d spend hours poring over my early chapter books and occasionally play with my stuffed animals but never partake in the elaborate doll parties that my younger sister, Scheherazade, hosted in the same bedroom. Her desire for dolls—porcelain and plastic—always outmatched my disdain for them. But, her objects of affection made more sense to my mother than my other preference. Books, she understood. My desire to play sports outside with my boy neighbors posed a different risk. So, while she encouraged my reading, she tried to curtail my gender rebellion. Thus, dolls, especially Barbie, became the first of our many battles over femininity.

Given that history, how did I, in my mid-life, end up dressing up as Barbie this past Halloween? More accurately, what made me determined to play President Barbie, don a magenta-pink jumpsuit, matching sunglasses, a white sash with blue lettering bearing my governmental title, and encourage my husband, Solomon, to be Malibu Ken? My best answer: I got caught up in the summer frenzy of Barbiemania. More specifically, I was so wrapped up in Greta Gerwig’s 2023 blockbuster, Barbie, and its promise of a feminist awakening on the big screen that I wanted to embody it in real life.

But, looking back on both the movie and my Barbie makeover, I can’t help thinking that feminism was a decoy. For as much as I appreciated the film’s deconstruction of its protagonist, Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie), I repeatedly found myself wondering and more worried about the future of her male sidekick Ken (Ryan Gosling) than I was intrigued by Barbie’s evolution. My response was, in part, a matter of screen time. Many critics have already noticed (and bemoaned) that the movie gave Ken the richer role and a more complicated character arc and also gives him and and his fellow Kens the major musical number. But he caught my eye for another reason, too.

Ken is the film’s great paradox because he is the one person who first names, then enthusiastically adopts and eventually disavows patriarchy. By doing so, he becomes both a synonym and symbol—a figure who grapples with sexism while also being the primary filter through which we understand its power. As a result, our emotions for Ken are equally contradictory, and rather than just being an indicator of how we feel about him, they also express our hopes, fears and desires for the kind of masculinity he represents. As I realized how much of our understanding of Barbie’s feminism was tied to our investment in Ken, a new question emerged. Specifically, I began to ask myself, “Was Hollywood actually trying to smash the patriarchy in 2023?”

It is hard not to see that the antagonists of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon—the sociopathic crime boss William Hale (Robert De Niro) and his homicidal nephew Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) who conspire to steal land from the Osage people in Oklahoma—as anything other than the embodiment of patriarchal violence. And though their greed, racism and blatant disregard of indigenous land rights when oil is found on Osage land is the main plot of the movie, it is through their relationship with each other and Burkhart’s marriage to his Osage wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), that Scorsese shows the deeply intimate havoc caused by male violence.

It is domestic violence when Ernest poisons Mollie, and mass violence when Hale orders the murder of more than 20 people to acquire their land. Scale is taken up even more in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, a film that doesn’t necessarily claim to be critical of patriarchy. But, like Ridley Scott’s even more controversial Napoleon, both movies depict their historical subjects, the nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) and French emperor and military leader Napoleon Bonaparte (Joaquin Phoenix), in wartime and as the chief architects of global dominance over other countries and people.

Ken is the film’s great paradox because he is the one person who first names, then enthusiastically adopts and eventually disavows patriarchy.”

In other words, these are movies that focus on the pernicious impact that systems, primarily governed by men, have had on the world: Hale and Burkhart’s attempt to wipe out entire family bloodlines in the Osage nation, Oppenheimer’s design of the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and Napoleon’s early nineteenth-century conflicts leading to the deaths of over three million people. I do not think most critics would remark on the feminist ethos of these films. But, because I watched them so closely to each other, I could not isolate them from each other. Instead, their subtexts gave us a pattern: the pain of patriarchal violence writ large.

This brings me to the Marvel movie universe. Though I am not the most avowed franchise fan, I am raising one. My tween daughter, Seneca, has somehow watched all of the Avengers films chronologically. Initially without my knowing, and then ultimately convincing me to take her to see The Marvels. Helmed by Nia DaCosta (Little Woods and Candyman), the movie departed from others in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, including the 2019 Captain Marvel, by featuring three female leads from different racial and cultural backgrounds: the white superhero Carol Danvers/Captain Marvel, (Brie Larson), the African American S.A.B.E.R. astronaut Monica Rambeau (Teyonah Parris), and the shapeshifting and cosmic-energy-toting Pakistani-American Kamala Khan/Ms. Marvel (Iman Vellani).

Once these characters realize their powers are linked and they must team up to take on the villainess Dar-Benn (Zawe Ashton) and save the world, the movie depicts shared leadership and collective action. Though the film makes no implicit political critique of patriarchy, it does offer a temporary alternative. That it had the lowest opening weekend in the MCU’s history tells us a lot, too. It neither benefited from a post-Barbie bliss nor appealed to Marvel’s mainly white, male, millennial audience fanbase in significant numbers.

Perhaps nothing fashioned itself as taking on the male gaze so forthrightly as did Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things, a movie that follows Bella (Emma Stone), a pregnant woman who commits suicide and then is resurrected when a doctor (William Dafoe) swaps her unborn baby’s brain for hers. Once revived, she then has to relearn being a woman in the world—which here means that she is unstable, randomly violent, hypersexual, infantile, curious, embattled and a constant object of male desire.

In this sense, Bella is both a child and a doll, shaping herself as various men pursue and try to control her. The result, as New York Times reporter Kyle Buchanan noted after the film’s Venice premiere, is a “Bizarro Barbie” who ups the ante on Gerwig’s feminist themes “to their R-rated extreme, interrogating gender dynamics and sexuality from nearly every angle.” And though Bella successfully fights back against the patriarchs in her life, I wanted to know if her victory was hers alone, or if it could help other women escape and own their fate, too.

For that ending, I’ve turned to The Color Purple, Blitz Bazawule’s musical reimagining of Alice Walker’s 1983-Pulitzer-winning novel and Steven Spielberg’s 1985 movie classic. Set in rural Georgia in the early twentieth century, the story is about Celie, a teenage Black girl who is repeatedly violated and twice impregnated by her pa, a man she considers her father after her mother dies. She then is forced to marry and care for the children of an older widow named Albert, who beats her and separates her from her sister, Nettie. The movie traces Celie’s (Fantasia Barrino) journey to self as she learns to speak up for herself, embraces her sexuality and desire for women, and becomes the center of her community that she has remade in her image.

While Bazawule stays true to the feminist intent of Walker’s vision, he also expands it through his emphasis on Albert’s son Harpo’s (Corey Hawkins) arc and his repairing of his relationship with his former wife, Sofia (Danielle Brooks), who left him over domestic violence. Through Harpo, we see the price of conforming to patriarchal violence and then what new freedoms are possible for all the stories when it is finally rejected.

And this is ultimately what bothered me about Barbie. Though Ken resolves his fate as a man who refutes sexism, I was unclear why Barbie had to leave her friends and the more democratic space of Barbie Land for the very messy patriarchy of the United States. She, of course, is no longer a doll, left to the whims of the children who play with her or the adults who project themselves back onto her. The movie suggests freedom in being human, even if it means being a woman who seeks out a gynecologist in a post-Dobbs America. But I wanted her to stage a rebellion—in concert with others—and either take them with her or stay behind to help them build a new vision of Barbieland, where the Kens and Barbies could both thrive. Perhaps, though, I am asking too much of Hollywood, and definitely of the Barbie doll parent company of Mattel, for that matter.

However, the movie’s political message wasn’t lost on the most vocal movie critics I know: my children. When we left the theater, my seven-year-old son, Sidney, posed in front of the Barbie sign with pink sunglasses and a cowboy hat. Soon after, my husband Solomon picked us up from the theater and asked Sidney and Seneca if they liked Barbie and what it was about.

In seconds and unison, they both replied, “Patriarchy.”

And for now, that might be enough.

SALAMISHAH TILLET

The Henry Rutgers Professor of Creative Writing and African American and African Studies and Executive Director of Express Newark, a center for socially engaged art and design at Rutgers University- Newark. Tillet won the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism for her work as a contributing critic at large for The New York Times. She is the author of In Search of the Color Purple: The Story of an American Masterpiece (Abrams, 2021), among other books. For TheWrapBook, shewrote “How Hollywood Tried to Smash the Patriarchy in 2023.”

The post How Hollywood Tried To Smash The Patriarchy in 2023 appeared first on TheWrap.