Hollywood’s Labor Force Does Not Reflect California’s Diversity

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

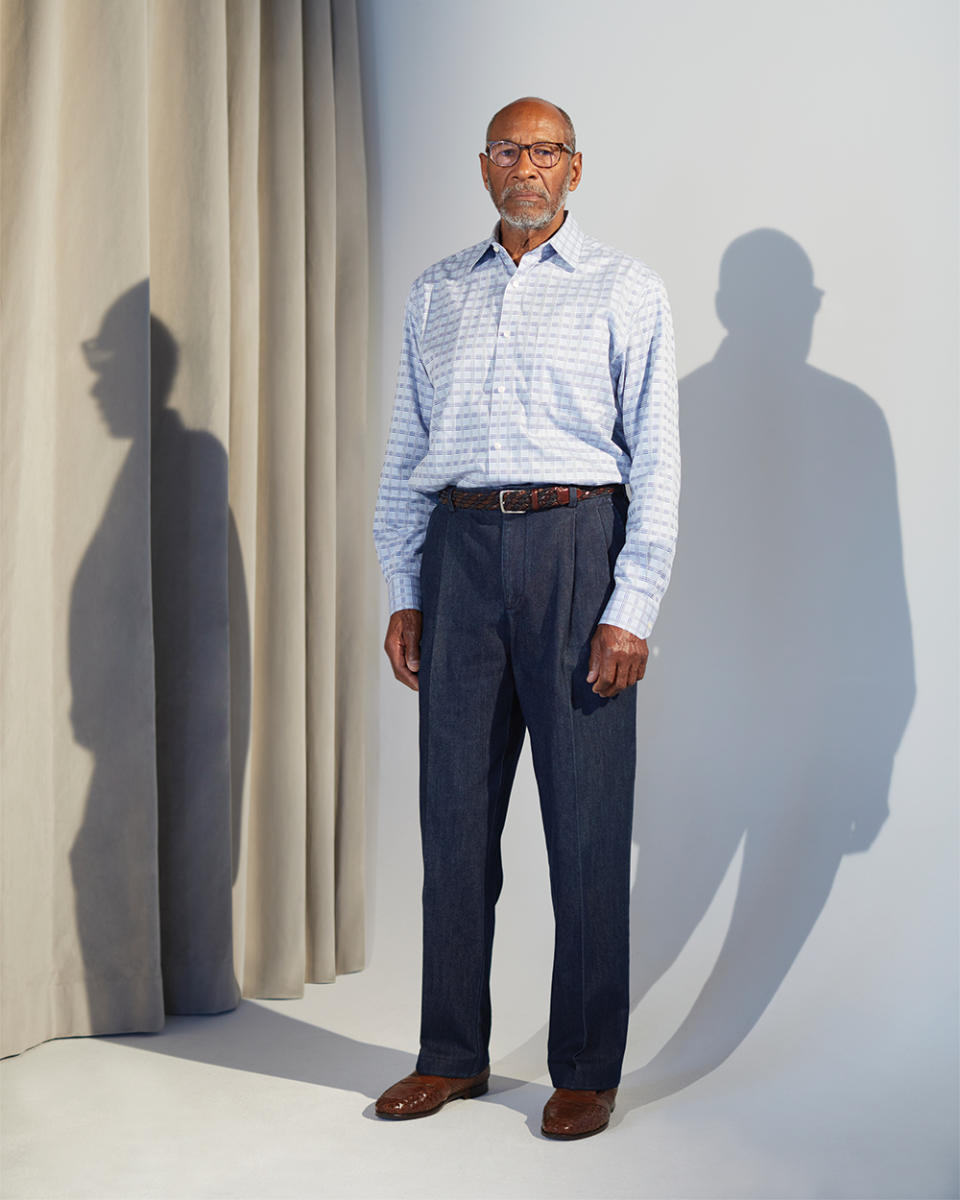

Norm Langley was one of the first Black camera operators to break into the business in the early 1970s, when the industry was facing government pressure to diversify. He had a 38-year career, working on TV shows like “The Practice” and movies including “The Color Purple” and “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.”

In his retirement, he has grown increasingly agitated that his union — IATSE Local 600 — never did more to recruit minorities. When Langley started his career, he said the goal was to bring Black membership up to 10%. Last year, in the wake of the George Floyd protests, he called the union president and asked if that target had ever been met.

More from Variety

Costume Designer Jenny Beavan's Oscar Suit Honors Guild's Pay Equity Fight

IATSE Calls Out Academy's 'Detrimental' Decision to Reformat Oscars Telecast

'West Side Story,' 'Cyrano,' 'Dune,' 'Coming 2 America' Among Costume Designers Guild Nominations

“He said, ‘I can’t give you that information,’” Langley says.

In a state that is plurality Latino and where Asian Americans are the fastest-growing group, white people still make up the vast majority of the film and TV workforce. Decades of efforts to expand opportunity for those jobs — which come with good salaries and great benefits — have not changed that fact.

The fight for diversity in Hollywood comes down to a battle over numbers. In the past decade, researchers from UCLA and USC have undertaken painstaking statistical analyses of films and TV shows, tabulating racial and gender disparities among actors, writers and directors — and fueling a movement for greater representation.

But in physical production, among the painters and hairstylists and boom operators who comprise the bulk of Hollywood’s workforce, the numbers are scarce. Most unions do not collect data on Black, Latino or Asian American membership, and other sources are spotty at best. That has left a huge gap in the debate over representation in Hollywood.

So Variety did its own study.

We compiled more than 51,000 names from union rosters and then hired Political Data Inc. to match the names against surname dictionaries. The method is not perfect. It cannot be used to estimate Black or multiracial populations. But Variety was able to estimate Latino and Asian American representation for 21 entertainment unions.

The study found that overall, 16.1% of the below-the-line workforce is Latino and 4.7% is Asian American. Both groups are dramatically underrepresented compared with their share of the state population (39.4% and 15.5%, respectively).

Variety looked for other data sources on Black representation. Three unions — Plasterers Local 755, IATSE Local 700 and IBEW Local 40 — provided their own survey data, showing Black membership of 3.5%, 4% and 5%, respectively. (The Black population of California is 6.5%.)

The state’s film commission, meanwhile, has reported that Black workers made up 7.2% of the jobs subsidized by the state tax credit program from 2015-20 — and 70% of those whose race could be determined were white. That data remains incomplete.

For Latino and Asian American representation, the Variety study provides the first comprehensive picture across Hollywood unions, and shows significant variation among them. Latinos are clustered in blue-collar trades such as laborers and plumbers, while Asian Americans are underrepresented almost everywhere except among animators.

The study found that some guilds were above the industry average with one group and below it with the other. Blue-collar positions like propmakers, painters, drivers and grips tended to skew more Latino and less Asian. Cinematographers, editors, art directors and the like tended to skew more Asian American and less Latino. In all of these jobs, both groups were underrepresented compared with the state population, but the way they were underrepresented was strikingly different.

The study comes as California and other states are trying to leverage their film and TV tax credit programs to push for greater diversity. Among lawmakers, there is growing unease that taxpayers are asked to subsidize middle-class jobs in an industry that is much whiter than the population.

“We are providing this incredible tax benefit,” says California Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo, who is leading diversity efforts in Sacramento. “It needs to be reflective of the people of the state.”

The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees is also facing pressure from its own members. Last year, in response to protests from nonwhite theater workers in New York, the union admitted it had fallen short on diversity.

“We can do better,” the union said in a statement. “We must do better. We will do better.”

But without data, nobody can say what “better” is. Which locals have done a good job? Which have not? Have some been better among some groups than others, and why?

The Variety study begins to answer those questions.

“As an industry, we have a long way to go,” says Carl Mulert, national business agent of United Scenic Artists Local 829. “We believe firmly that you can’t actually make change until you have the data.”

Clifford Alexander Jr. was another big believer in data. In the late 1960s, he was the chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In 1969 — following years of protest from the NAACP and other minority groups — he held a hearing on employment discrimination in Hollywood.

“We here at the EEOC believe in numbers,” Alexander said in 1968. “Our most valid standard is in numbers . ... The only accomplishment is when we look at all those numbers and see a vast improvement in the picture.” On March 13, 1969, Alexander called witnesses from IATSE, the major studios and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. He asked them for numbers.

Josef Bernay, representing IATSE, rattled off diversity statistics for three guilds. In Local 790, the Illustrators and Matte Artists, there were 50 members, of which one was Asian American. In Local 847, the Set Designers and Model Makers, there were 155 members. One was Black, three were Latino, four were Asian American and one was Native American. And in Local 854, the Story Analysts, there were 61 members, two of which were Black.

“We do not practice discrimination,” Bernay told the commission. “Anyone who wants to apply at any of these three locals is welcome to.”

The commission did not buy that. At the end of the day, the EEOC general counsel announced that the numbers clearly showed that Hollywood engaged in discrimination. The next day, Variety declared: “Pix Discriminate in Jobs.”

After an extensive negotiation with the Justice Department, the industry agreed to create a minority training program. Langley was one of the first to benefit. He had been a Navy photographer and was admitted to the program’s second class of recruits in 1971.

“That was the greatest program they ever had in the motion picture industry,” Langley tells Variety. “And of course you know what happened. It did not last very long.”

Michael Buckner for Variety

By the early ’70s, the Justice Department had shifted its priorities and it did not monitor the industry’s compliance. After a couple more years, the program went by the wayside. In 1982, the NAACP again complained that Hollywood wasn’t doing enough to diversify.

“They still have never got the numbers they wanted 50 years ago,” says Langley. He has experienced the recent protests with a sense of déjà vu.

“This is probably a time where the breakthrough could happen,” he says. “It definitely should be continuously monitored. Otherwise, the same thing is going to happen in each generation.”

Film industry jobs have become a rarity in an era of deindustrialization. They can provide a six-figure income, along with gold-plated benefits, to workers who may not have a college degree.

“Our guys do just swell,” says Alex Aguilar, business manager of Laborers’ Local 724. “You see these kids coming out of high school, and after five, six, seven years in the union, they’re buying a home. I hear that, and it’s like music to my ears. There’s nothing better than that.”

To get into the union, workers generally need to put in a fixed number of days on union projects. But to get those jobs as a nonmember, it often helps to know someone — preferably a family member who is in the union.

“That’s how most people have gotten in,” says Steve Dayan, secretary-treasurer of Teamsters Local 399. “Some members, as soon as their kids are out of high school, they suck them into the film industry.”

Says Aguilar: “Our industry is built on nepotism.”

Over the years, that has made it harder for Black, Latino and Asian American workers to break into the business.

“The people who get the jobs are the sons and daughters of the people who have the jobs, who tend to be white,” says Robert Cantore, a retired attorney who represented several Hollywood locals.

Krishnia Parker/Assembly Democratic Caucus

Rafael “Apache” Gonzalez heard about a job as a set dresser from his brother in 2006. His first job was on “Tenderness,” a Russell Crowe feature that was filmed in New York. From then on, he worked steadily, amassing enough hours to join IATSE Local 52, the union that represents about 3,700 below-the-line film and TV workers in New York.

But to get in, Gonzalez also had to pass a test. He repeatedly asked to take the test and was repeatedly denied. At the same time, he saw others being “walked in” to the union with less experience — including one person he supervised.

“They were just letting their friends and family in,” Gonzalez tells Variety. “The nepotism was ridiculous.”

Gonzalez complained and quickly saw his work opportunities dry up. He filed an EEOC complaint in 2011, and his attorney took the matter to the New York State Attorney General’s office, which launched an investigation.

In 2014, the A.G.’s office concluded that Local 52 “follows a policy of nepotism in its admissions process — that is, a preference for friends and family,” and that the policy “results in the exclusion of African American and Latino applicants.”

The union and the A.G.’s office agreed to an “assurance of discontinuance,” under which Local 52 admitted no wrongdoing but agreed to certain reforms in exchange for terminating the investigation. The union — which did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story — was subject to monitoring for three years and had to implement a diversity plan.

The union also paid a $475,000 fine, of which $375,000 went into a fund for 14 applicants — mostly Latino — who had been denied admission. Variety spoke with two of them, who both requested anonymity. They are still waiting to be admitted to the union.

“At the end of the day, the union does what they want,” says one of them.

The other says the local remains largely white. “There’s a lot of nepotism in this union,” he says. “I’m way, way more qualified than the assholes they sent in last time.”

Gonzalez filed a separate lawsuit and eventually settled it for nearly $500,000, though he says his attorneys took most of that. He also switched crafts, knowing he would never be admitted to Local 52. He learned graphic design and joined United Scenic Artists Local 829, where he serves on the diversity committee. He says that he recently worked on “West Side Story,” though he still faces retaliation from Local 52 members who consider him a snitch.

“An idiot on Facebook said I should be shot,” he says.

Variety was able to obtain the names of nearly 3,600 Local 52 members from the New York Production Guide. The surname analysis showed the union is 4.2% Latino and 2.1% Asian American — ranking it among the least diverse unions Variety analyzed.

“Nothing changed,” Gonzalez says.

Before Josef Bernay took his seat on March 13, 1969, the EEOC heard from Ray Martel, an actor with a few bit parts to his name who had gotten involved with the Mexican American Political Assn.

Martel came to the hearing at the urging of civil rights leader Bert Corona, and he did not hold back in his testimony, threatening at one point to “tear these studios down.”

“We have hundreds of thousands of Mexican Americans out here, and yet when you go to the studios, you never see a brown face,” he said.

He was asked if any had applied for jobs, and answered that they had all been rejected.

“In some of these unions, you practically have to inherit a job,” he said. “I think what we have here is an industry that is steeped in groupism and nepotism. ... By the time that you weed out all the people involved in nepotism and cronyism and these personal favorites, that leaves nothing for the Mexican American.”

In a recent interview, Martel says the industry never took the complaints seriously. He recalls once being in a meeting with Lew Wasserman, the late legendary power broker who represented the studios. At one point a MAPA representative said that the discussion was going nowhere, and it would be better to take the association’s complaints to the government.

“Lew Wasserman laughed out loud,” Martel recalls. “He said, ‘You want to talk to Ronald Reagan? I got his private phone number.’ It was a joke to them.”

Martel’s acting career never amounted to much, and he later worked as a liquor salesman and a sales manager in the mattress business.

Now in his 80s, he believes the EEOC hearing was a sham.

“I feel like a failure,” he says. “I feel like we got nothing done. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be talking about it 50 years later.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.