How Hollywood Hid Rock Hudson, Its Biggest Gay Movie Star

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

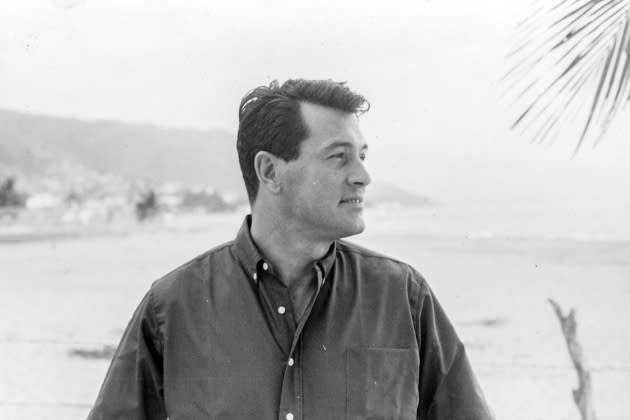

Like a lot of all-American dreamboats, Roy Harold Fitzgerald (née Scherer Jr.) made his way to Hollywood after World War II, making good on the offer to look up a friend’s brother should he ever find himself in the greater Los Angeles area. The ex-Navy mechanic had matinee-idol looks, a cornfed wholesomeness, and a lean-beefcake physique; anyone who took one look at Fitzgerald would have immediately thought, “He ought to be in pictures.” The young man had been told that acting was “sissy stuff” when he was growing up in the Midwest, and that he’d have to become a policeman or a fireman… y’know, real masculine jobs. But here he was near the edge of the Dream Factory’s assembly line, and talent scout Henry Wilson instinctively knew that the kid would be big.

The fact that Fitzgerald was gay wasn’t an issue — this was Hollywood, after all — though he’d have to make sure he kept it a secret. There were protocols in place for that, from arranged “dates” with starlets to suppressed news stories to underground clubs that catered to famous closeted clientele. The real problem, Wilson thought, was that damn name. So he rechristened him Rock Hudson. Who needs to be a cop when you have a hunky, manly name like that?

More from Rolling Stone

Legendary Concert Promoter Ron Delsener Looks Back On 60 Years of Live Music Madness

Jennifer Lawrence, A-List Actors Threaten to Strike in Letter to SAG

'My So-Called Life' and the Coming-Out Scene That Changed TV History

Two things immediately come to mind when we think of Hudson now: How he was the epitome of a studio-system leading man circa the mid-20th century, who graduated from cheap Westerns and cheaper adventure movies to Universal grade-A projects; and how did his death from an AIDS-related illness in 1985 made him both the reluctant face of the disease and forced the general public to talk about it in earnest? Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed, the new HBO documentary on the handsome man they called Rock, is less interested in his career and far more fascinated by his second, “open-secret” life. It’s intrigued by the man on the screen, but way, way more into the real Hudson. Specifically, the person who managed to keep up his masquerade as the straight guy next door while still living out loud as quietly as possible. Bring on the contradictions!

Oh, the doc gets into the origin story and the filmography a bit, giving us a quick glimpse of the gangly kid from Illinois who’d eventually become, per one of the voiceovers, “the Tom Cruise of his day.” A split-screen montage of his early work as a background and/or bit player gives you the sense that nobody knew what to do with Rock yet, other than take advantage of that to-die-for jawline. Eventually, he nabs a ridiculous comedy called Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952), which introduces him to director Douglas Sirk. The German émigré casts Hudson in a series of glamorous melodramas, starting with Magnificent Obsession (1954), and then our man is off to the A-list races. He also ends up starring in a surprising number of movies that have the actor saying a host of lines and playing scenes that, with the benefit of hindsight and a keenly honed sense of camp, now read as coded transmissions from the celluloid closet. Seriously, have you watched Pillow Talk recently?!

If you’ve seen Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, Mark Rappaport’s experimental 1991 doc that ties all of those screen moments together, then you’re familiar with these wink-nudge excavations and hidden-in-plain-sight readings. What All That Heaven Allowed has that the earlier doc doesn’t, however, are what appears to be filmmaker Stephen Kijak’s access to Hudson’s actual home movies — not to mention the benefit of a platform like HBO retelling this story to a wider, now far more receptive audience. And it’s the emphasis on the shrouded aspects of his existence in the spotlight, along with testimonials from Hudson’s many friends, lovers, friendly ex-lovers, temporary boyfriends and occasional hookups, that makes this posthumous portrait both a historical corrective and a frustratingly lopsided viewing experience. Never mind the evidence to support the claim that no one understood how “subtle” an actor Hudson was; he definitely could be, you just wouldn’t necessarily know how or why from the doc. Let’s talk about what happened behind the curtain, which feels curiously unexamined from what happened on the screen (even Seconds, which gets the most lip service, gets short shrift) and thus feels like only half the narrative.

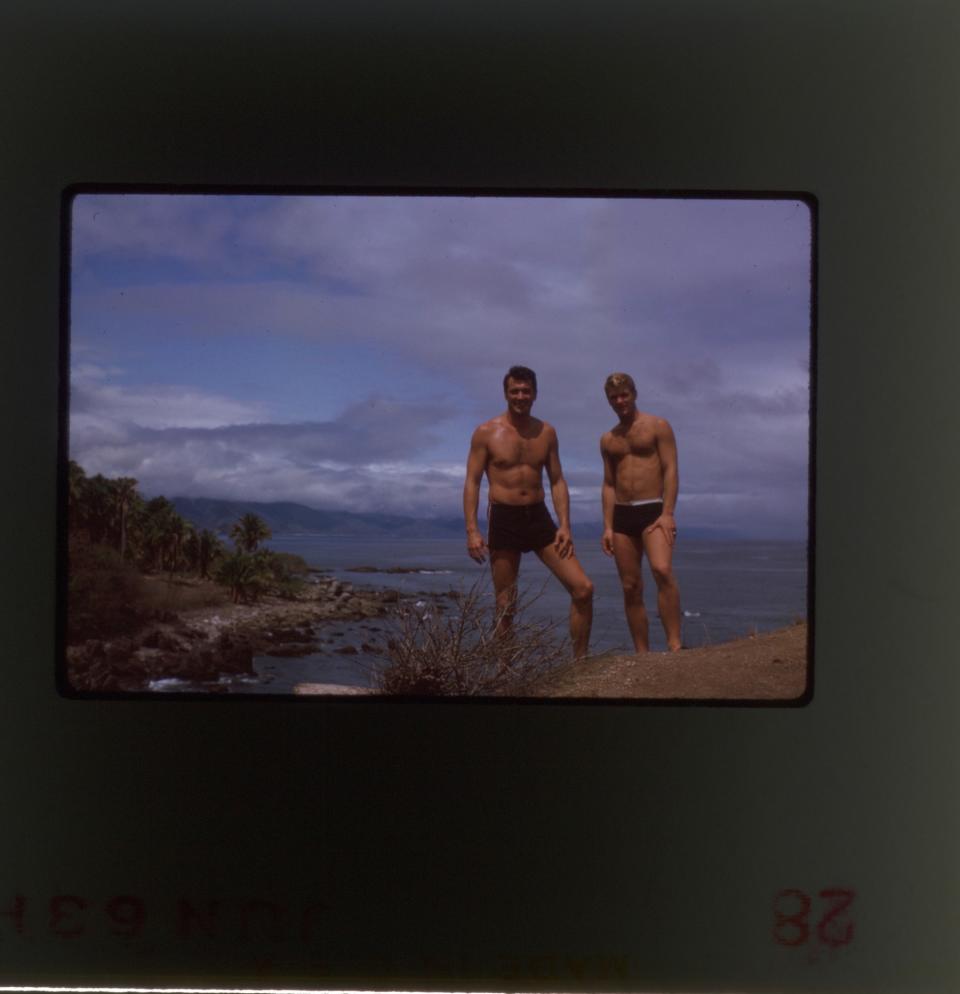

Which, look, to be fair: no one needs yet another “Hooray for Hollywood!” clips extravaganza posing as a documentary. And Hudson was, by many accounts, “a sexual gladiator” who regularly entertained pool parties and gatherings at “the Castle,” his L.A. residence that became a stop and a safe space for the industry’s gay community. So much of Hudson’s story as a gay man revolves around his death, which the last third of All That Heaven Allowed deep-dives into in the name of painting Hudson as “a reluctant activist.” The benefit of this look back is that it wants you to know what Hudson’s life as a gay man was like as well, and that is where the corrective part comes in.

You do get a picture, not to mention literal snapshots, of Hudson’s active participation in relationships, all-male vacations, one-off romantic excursions and longtime friendships through, per a voiceover, bonding over “the shared misery of the closet.” Author Armistead Maupin, who met and slept with Hudson right as Tales of the City was turning him into a literary sensation, talks about trying to convince the McMillan & Wife-era star to come out, which would be seen less as a professional death knell and more of a liberating statement. The first part is debatable, but the second isn’t — and Hudson still felt the need to be seen as the epitome of straightness. He became a mentor to other closeted performers. There’s a genuine sense that although the star was forced to lead a dual existence, it was still a happy one on the less-publicized side of the fence. And while there isn’t what you’d call bombshell news here, there’s plenty for gossip-craving fanatics. Hudson’s prodigious, ah, talents are confirmed in a unique first-person anecdote. Apparently, when you’re famous and gorgeous, heaven allows for just about anything.

Anything except telling people that you, the guy who helped turn Giant into an American cinema landmark and made all of those Doris Day rom-coms, love men instead of women to paying customers circa 1946 to 1985. Therein lies the rub. It’s best to look at All That Heaven Allowed less as a Rock doc and more as a chronicle of Hollywood’s system of subterfuge and suggestion, all built around protecting and/or punishing those who preferred the company of their own sex. Hudson was mandated a number of public appearances with actresses, and was strongly encouraged, if not shoved into a marriage with Phyllis Gates. A picture of him with another man at a bar was purchased and buried, for what you’d suspect was an extravagant but not-unusual price. Magazines like Confidential would “wonder” aloud if actors like Hudson were getting up to things the public disapproved of; it would take Wilson throwing another client, Tab Hunter, to the tabloid wolves to get them off Rock’s scent. Like countless other celebrities, Hudson had to pay a price and play the game. It was all that Hollywood, and by extension America, would allow.

Best of Rolling Stone