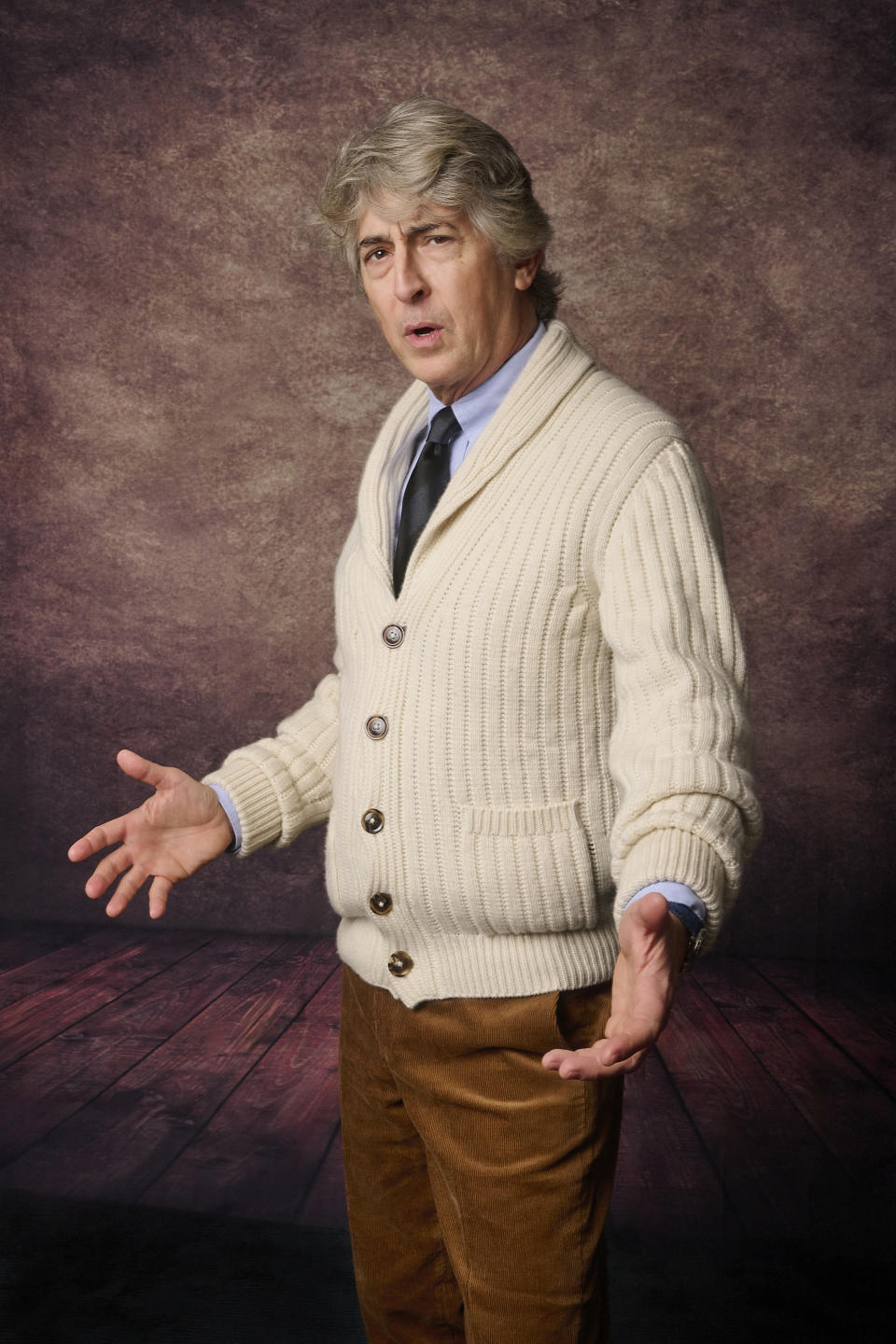

‘The Holdovers’: Alexander Payne Goes Back To School With Paul Giamatti, Da’Vine Joy Randolph And Newcomer Dominic Sessa

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Back in 2004, during a press tour for Sideways — Alexander Payne’s wine-soaked buddy movie starring Paul Giamatti as a depressive divorcé — the filmmaker and the actor were in Omaha in front of an audience.

In a moment of showmanship, Payne whipped out a local phone book, declaring Giamatti so skilled, he could make even that sound interesting. And sure enough, as Giamatti recited the listings, he brought the house down. “Thanks for rolling with that stunt,” Payne tells Giamatti now, some 20 years later, in a New York City hotel room, where they are, once again, on a press tour.

More from Deadline

‘The Holdovers’: Read The Screenplay That Helped Get Alexander Payne Back Behind The Camera

Indie Film's Breakout Year: Good Movies Gain Traction Amid Strikes & Superhero Fatigue

The film reuniting them is The Holdovers and Payne designed Giamatti’s role just for him. Paul Hunham is a beleaguered Classics professor at Barton Academy, a New England boarding school steeped in history and privilege. Like Giamatti’s Sideways character, Hunham also likes a drink (more on that later), but the other throughline is a theme Payne’s films have often favored — something The Holdovers screenwriter David Hemingson calls “quiet heroism.”

Nobody likes the wall-eyed and odiferous Hunham, yet on he soldiers, railing against his pupils’ entitlement, a curmudgeonly Scrooge doling out homework for the Christmas break. He believes in his teaching mission and will get it done, regardless the effect on his own popularity.

Payne recalls his own version of Hunham from childhood — a “prick Latin teacher” from his Jesuit school. “Father Michael Hindelang. A magnificent Saint Prick. He made kids cry in class. It was a centuries-old method of, how do you say the word? Pedagogy?”

Payne thought of him often during filming. “The moment class was over, and you talked to him, he was the nicest guy. So, it was, ‘You’re willing to be f*cking hated in order to instill this discipline in us?’ The willingness to be disliked. In fact, welcoming it.”

“That’s definitely in the movie,” Giamatti says.

An early scene shows this exact characteristic in Hunham. Barton’s headmaster Dr. Hardy Woodrup — who is, in fact, a former pupil of Hunham’s — sits behind his stately desk, basking in the glow of a gifted bottle of Louis XIII cognac (retailing today at around $4,000). He berates Hunham for failing a pupil whose parents have deep pockets. But Hunham will not bend. He tells Woodrup: “Our one true purpose is to produce young men of good character, and we cannot sacrifice our integrity on the altar of their entitlement.”

And then Hunham is landed with his worst nightmare: the task of caretaking ‘the holdovers’ — those kids who will remain in school over the holidays. That group will eventually be whittled down to one boy — the insolent Angus Tully, played by newcomer Dominic Sessa — and together with Mary, Da’Vine Joy Randolph’s recently-bereaved school cook, Hunham will attempt to be in loco parentis.

The trio make a motley sort of crew, but it turns out that each has something to teach the other. In the hands of another director, that message, along with the Christmassy, ye olde East Coast setting, might devolve into syrup. Instead, The Holdovers goes after the twisted humor and painful truth of the repressed and lonely: Tully, the privileged pupil whose parents don’t want him at Christmas; Hunham, the hated teacher with no family, and Mary, the low-income employee mourning her beloved son. All three know what it is to be left behind.

Hunham is both a sympathetic figure for his awkward solitude, and his own worst enemy for his pedantry — peppering his speech with incomprehensible Latin, and even taking a man dressed as Santa to task for his historical inaccuracy. And it is clear that Barton, which is also his alma mater, is all he has.

It was always Payne’s wish to work with Giamatti again, it was just a case of timing and the right project. So, when Payne read David Hemingson’s television pilot, loosely based on his own boarding school experience, an idea for a movie began to form. And, as Payne and Hemingson batted ideas back and forth, the director imagined Giamatti in the professor role, and called him up to tell him as much.

“I was like, ‘Fine, where do you want me to show up?’” Giamatti recalls.

Payne later told his longtime editor Kevin Tent that he and Giamatti were both “just giddy” to be working together again. “I think there’s just deep, deep mutual respect for each other,” Tent says. “And they’re both so good at what they do, and they both just have enormous respect for each other and they’re so collaborative.”

When Giamatti read the script, he felt its authenticity, and he has a particularly gimlet eye for this stuff since he himself went to an East Coast boarding school — Choate, a rival school to Deerfield Academy, where among several other schools, the movie would be shot.

“He gets this stuff really right,” Giamatti says of Payne. “Oftentimes, classroom stuff bothers me in movies because I don’t believe it.”

“Like what, for example?” Payne cuts in.

“I mean, offhand, I just often feel like it just isn’t convincing. It’s like I don’t believe this is a real classroom. I don’t believe this is really a teacher. It just is all too simplistic-seeming and sounding. But this actually felt… I believed all the details, even in the script. I was like, ‘I buy this.’”

Hemingson came up with the character of Mary the school cook, and Payne had admired Randolph’s work in Dolemite Is My Name. Randolph herself instantly related to the story’s setting and theme. “I studied at prep schools my entire primary school education, and then went to Yale,” she says. “I also know what it feels like to feel othered as an outsider.”

Once she was cast, Payne mailed her a carton of cigarettes as a sort of invitation. Mary is a smoker and Randolph is not, but she would learn to make it real. And she dove deep into understanding the mindset of a woman who has lost her only son.

“I tried to chart her from the start of the movie to the end of the movie, to go through all the stages of grief,” Randolph says. “I quickly understood, while I was doing it, but also in my research from reading the DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders] and certain psychological novels, that this whole ‘stages of grief’ and the order that they put it in, I don’t know who came up with that, but a lot of times it’s false. Sometimes it happens out of that projected order. And you could be here, and then jump back to anger or denial.”

She also started to feel out Mary’s long spaces of silence in Hemingson’s script. “David, beautifully, wrote almost like it would turn into a novel. He would just write in prose the environment. And I had to fill three pages, which usually translated as 20 to 30 minutes of me being on camera, just being in my room doing a puzzle and smoking a cigarette. And from that, I had to create a whole world for myself.”

The choice to shoot at various

Massachusetts prep schools would provoke in Giamatti a “triggering” memory of freezing cold bus rides for swim meets. It would also be where they would find the actor to play Tully.

Casting director Susan Shopmaker, empty-handed after so many actor auditions, had begun searching school drama departments, and at Deerfield, she finally found Sessa.

After several meetings with Payne and Giamatti separately, Sessa realized they were actually serious about casting him. He had previously only known Payne’s film The Descendants — “We studied the book in eighth grade,” he says. During what would be a final audition, Sessa and Giamatti read through the entire script for Payne.

“[Payne] didn’t say anything about what we had read or what we had done. There weren’t really any acting notes,” Sessa says. “We finished. It was silent for five to 10 seconds, and he was just like, ‘OK, come be in my movie.’”

If shooting at Deerfield felt surreal for former prep school pupil Giamatti, it was “the twilight zone” for the 18-year-old Sessa, who would be shooting scenes in his regular, real-life classrooms.

In The Holdovers, the year is 1970, an era Payne chose partly for practical reasons, he says. “We knew it couldn’t be a contemporary story, because there are no more single-sex boarding schools. Somehow Hemingson said, ‘What about 1970?’ And it just felt like an unusual year in which to set a movie. And then just for screenwriting tools, it gave him higher stakes for the characters, the sword of Damocles hanging over the kids’ heads.”

Mary’s son Curtis — a recent graduate of Barton — has recently been killed in Vietnam, so the era brought in “the war’s impact on her, giving mournfulness and poignancy to her life,” Payne says.

He went all in, having ’70s title cards created for Focus Features — before the studio even existed — complete with all the scratches and pops of a well-worn cinema reel.

And then there’s the soundtrack. Along with editor Tent and music editor Richard Ford, Payne selected a mixture of ’70s-era artists and contemporary music with a throwback sound. He also set his heart on one particular song, “The Wind” by Cat Stevens, which, following negotiations with the singer, ultimately ate up a hefty chunk of budget.

“All I know is if we ever meet for lunch, when the check comes, I’m going to the bathroom,” Payne says.

Ahead of the shoot, Payne set about showing some films to Sessa. “Just ones I like that more or less straddled 1970,” he says. “Dominic had never seen The Graduate, so you had a sense of the alienated young person with an anti-authoritarian streak. That was a common kind of archetype prototype of the period. So, we screened that, three Hal Ashby pictures, The Landlord, Harold and Maude, The Last Detail and Paper Moon — one of my favorites from that period. I watch that about once a year. And then, I think All the President’s Men maybe. Not that any single one of those films was to be the influence on the film, but just so my colleagues and me were splashing around in those same waters.”

Once they were gathered on location, Giamatti felt “it was kind of nice to go back to that world. As rough as it was, you’ve got to love all that. The old wood and the leather. That stuff is really seductive. The old dining halls… and the guy I’m playing loves the fantasy of that stuff.”

Randolph also found a sense of recognition in Giamatti, both having studied drama at Yale.

“The only way I can describe it for me would be me being in Tokyo and being like, ‘I’m struggling. I don’t know what you’re saying,’” says Randolph, “And being in a mass of people and having one person speaking English and being like, ‘My person!’ And then I was like, ‘Oh, we’re going to be good.’”

Sessa had never done any acting on screen before, only on the school stage, as he says, “The process, the bulk of it, was beating out the performative aspects that I guess become natural when you do a lot of stage acting. You really are bringing that performance through the space to an audience.”

But his newness to film was in Randolph’s mind hugely helpful.

“With Dominic, it was just, similarly for myself, when I went to Yale, I hadn’t had much prior training at all, actually, maybe a year of acting, whatever that means at an undergrad, non-conservatory level. And so, something that I saw in him and that I tried to help foster and facilitate, what he had at his advantage, was that he didn’t have so much inundated practices already. Like a baby, and I say that in the best sense, when a baby is young, you can throw them in the water and innately they’re doing breaststroke and they’re swimming. So similarly, we threw him in this situation, and he quickly caught on, adapted, threw the ball back at us, you know what I mean?

“I think if we had a child star or a Disney star, I’m telling you right now, they could have been lovely, but it would’ve been a different experience because they would’ve come into it with their own things. By him being so open and generous and willing to learn, it just afforded us a much more, in my opinion, fruitful experience.”

And Giamatti found Sessa’s lack of training personally inspiring. “He would advocate for his character in a way that I’d kind of forgotten about. I’m more adept and professional and whatever. But sometimes he would step back and go, ‘I don’t know. Was that…?’ Because I’ll just be like, ‘What do you want me to do? Where do you want me to go? Sure.’ You know what I mean? It’s like I’m a dog in some ways that’s been trained. And without all of that stuff, there was a really great freshness to that thing. It was really great sometimes. It made me step back and slow down and think things through.”

“It’s so nice when actors bring you little gifts,” Payne says, citing Sessa’s own decision to push two beds together for his character. “I never would’ve thought of that. Dom said, ‘Well, that’s what I would’ve done. I would’ve pushed two of the beds together.’ [I thought] Thank god you’re here. I can’t think of all that sh*t myself, I’m just the gatekeeper.”

“But you have no idea how much that doesn’t happen, how rare that is,” Giamatti tells him.

When I later repeat this to Sessa and Randolph, Sessa tells her it was actually she who taught him to advocate for himself. “When I saw you asking questions about your character, it’s like, ‘Maybe I can ask questions about my character?’”

Payne is nothing if not open to suggestions from his cast and crew. He recalls shooting a scene where Hunham and Tully walk through a Boston park, and in the background, a woman feeds a squirrel. He was determined to get this squirrel thing squared away and handed the woman a handful of nuts the dolly grip happened to have in his pocket. In the film, we see her in the corner of the screen for a second, the squirrel finally taking a nut from her hand.

So, I have to ask, why the squirrel?

“Because who doesn’t want to see a squirrel?”

“That poor woman,” says Giamatti.

It took about 10 takes and was the “best shot in the movie”, Payne says. But the reason he is telling this story is to credit the key grip for his expert input. “I had to move the camera, and the key grip whispers in my ear, ‘What if you just do it here?’ I go, ‘Oh, my god! Thank god you’re here!’”

Randolph brings up this aspect of Payne’s direction too. “I’m just so grateful to have worked with creatives that were so collaborative and open. Alexander didn’t have to be like that, as decorated a director as he is.”

One big takeaway for Sessa was Payne’s instruction to show less on camera.

“The great Jean-Louis Trintignant used to say that the best film actors are those who feel the most, but show the least,” Payne says. “The camera’s going to smell it on you. The big schnozzola of the camera smells it.”

And Payne is right up there with the camera. “He’s literally five feet away from you,” says Sessa, “he is literally the camera. He’s right there.”

“His face is up against the camera,” adds Randolph. There’s no video village. Now that, I’ve never experienced, even in the jobs I’ve done before, I’ve never heard of that. And I remember the first week I was like, ‘So Paul, does he leave at some point?’ And he says, ‘No.’

“In a way, at first it was daunting, it was different. I was like, ‘I feel like he’s invading my space a little bit.’ And then very quickly, it grew to be a comfort for me. I would look for him, like, ‘Where’s he going?’ I would wait for him.”

I tell Payne and Giamatti my favorite scene takes place in a Boston liquor store. Hunham and Tully have gone to Boston against school orders, because Mary has pushed Hunham to be kinder to the boy. And Hunham, forced into connection, begins to reveal he is not a simple Scrooge at all. He is, in fact, a little like Tully — a thread Payne will gently tug when we see they have been prescribed the same anti-depressant.

After a painfully revealing run-in with a former Harvard classmate, Hunham needs a drink. As he searches the liquor store shelves, Tully pushes him to explain why his Harvard roommate caused him to be kicked out of college.

Tully: You got kicked out of Harvard for cheating?

Hunham: No, I got kicked out of Harvard for hitting him.

Tully: You hit him? What, like punched him out?

Hunham: No. I hit him with a car.

The scene was a long walk-and-talk around the store caught in a single shot.

“I kept screwing my lines up terribly,” Giamatti says. “But it was great because it was one shot and you really wanted to do it like that, which is great, but I just kept blowing it.”

“A cook is only as good as the ingredients,” counters Payne, “so, if a pianist could play Liszt, give him Liszt to play. If you have actors who can sustain four pages at a crack, take advantage of it.”

But this is not Giamatti’s favorite scene. He prefers one with no dialogue at all: Hunham has taken Tully to an ice-skating rink, and as the boy careens around on the ice, the usually bah-humbug Hunham watches, smiling.

“That was something on the page I really liked,” Giamatti says. “And then to actually shoot it, I really enjoyed it because I was actually watching that kid Dom enjoy himself skating. And it was really, really nice to do.”

“It worked out nicely in the construction of the film,” Payne says, “because what precedes it is the professor being told [by Tully], ‘Everyone hates you, even your colleagues.’ And then watching the boy skate gives the audience a moment to sink into that feeling with the character. And then, who has given him this thing? That boy who’s now onto something else, which is a moment of joy. I mean, for me, that wordless ice-skating scene is the love scene. There’s love in that scene.”

That undercutting of deep sadness, the quick-switch to humor or joy — a Payne hallmark — is there even when Mary is alone on her couch, smoking, clearly desolate without her son. Payne won’t let us linger there even a beat too long. Instead, he switches to a genuinely funny TV show she’s watching. Then Hunham appears and she simply hands him a coffee cup of whiskey.

And here at the end comes Payne’s master stroke. It’s the kind of ending where we feel held but not patronized, satisfied but not mollified. Hunham has sacrificed his job, his entire life at Barton, to save Tully’s future. And, despite his old adage of “Barton men don’t lie”, he has indeed lied to protect the boy.

As Hunham throws the last of his things into a U-Haul, the pupils stare, gleefully whispering about their most-hated teacher’s departure. But Tully ignores them and approaches. He has only a vague idea of what Hunham has done for him, and he has no idea at all of what he himself has done for Hunham — a man who both needed to care about someone and to be pushed out of his rut in equal measure. As they stand there, with all that they understand about each other, they make only small talk. And it is the saddest and best of scenes.

“They don’t need to hug. It’s in their eyes,” Payne says.

And once again, in the midst of poignancy, Payne makes us laugh out loud. As Hunham drives away, he pulls a gleaming bottle from his bag — the Cognac from the headmaster’s desk. Taking a swig, he spits what must be about $200-worth out of the window.

“The old setup and payoff,” Payne says, smiling. “The smoking gun.”

Best of Deadline

TV Cancellations Photo Gallery: Series Ending In 2024 & Beyond

Hollywood & Media Deaths In 2024: Photo Gallery & Obituaries

2024 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.