HMS Terror: Identity of sailor on doomed 1845 Franklin expedition discovered using DNA

In 1845, Sir John Franklin gathered 129 sailors on two ships and set course for the Arctic, in an attempt to find the Northwest Passage.

After three punishing years in the freezing sea, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror ran out of food and became trapped in the ice. Despite a number of desperate escape attempts, all of the men perished.

Now, the skeletal remains of one of the sailors has been identified after expert DNA testing and genealogical analysis by a team of researchers.

DNA extracted from tooth and bone samples were confirmed to be the remains of Warrant Officer John Gregory, an engineer aboard HMS Erebus.

His DNA matched a sample obtained from a direct descendant of Mr Gregory, researchers from the University of Waterloo, Lakehead University, and Trent University found.

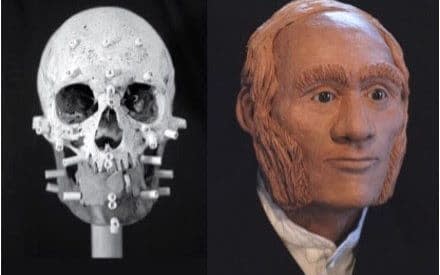

They used state-of-the-art facial reconstruction technology to ascertain what he would have looked like – blonde, with bushy eyebrows and large sideburns.

The remains of the officer were discovered on King William Island, Nunavut, a vast Canadian archipelago, in 1859 and were buried. In 2013, the grave was excavated and scientists began their search.

“We now know that John Gregory was one of three expedition personnel who died at this particular site, located at Erebus Bay on the southwest shore of King William Island,” said Douglas Stenton, adjunct professor of anthropology at Waterloo and co-author of a new paper about the discovery.

“Having John Gregory's remains being the first to be identified via genetic analysis is an incredible day for our family, as well as all those interested in the ill-fated Franklin expedition,” said Mr Gregory’s great-great-great grandson Jonathan Gregory, from Port Elizabeth, South Africa.

“The whole Gregory family is extremely grateful to the entire research team for their dedication and hard work, which is so critical in unlocking pieces of history that have been frozen in time for so long.”

The fateful voyage has been the subject of maritime intrigue for more than 150 years, but in 2014, after collaboration between scientists, divers and a local Inuit the wreckage of the HMS Erebus was discovered.

Two years later, the HMS Terror was found.

The fate of the men on the expedition has been poured over by historians, with rumours of cannibalism and evidence of sailors walking miles to try and reach Canadian outposts, but froze to death.

Even before the expedition, Sir John was known as “the man who ate his boots” because he ate his shoe leather on a previous trip to the Arctic when supplies ran out.

The skeletal remains of dozens of crew members have been found on King William Island, but until now, none had been positively identified.

“Analysis of these remains has also yielded other important information on these individuals, including their estimated age at death, stature, and health,” said Anne Keenleyside, Trent anthropology professor and co-author of the paper, which was published in the journal Polar Record.

To date, the DNA of 26 other members of the Franklin expedition have been extracted from remains found in nine archaeological sites in the area.

“We are extremely grateful to the Gregory family for sharing their family history with us and for providing DNA samples in support of our research,” added Prof Stenton.

“We’d like to encourage other descendants of members of the Franklin expedition to contact our team to see if their DNA can be used to identify the other 26 individuals.”

Prior to this DNA match, the last information about his voyage known to Mr Gregory’s family was in a letter he wrote to his wife Hannah from Greenland on July 9 1845 before the ships entered the Canadian Arctic.

This latest discovery helps to complete the story of the Franklin victims, says Robert Park, Waterloo anthropology professor and co-author. “The identification proves that Gregory survived three years locked in the ice on board HMS Erebus. But he perished 75 kilometres south at Erebus Bay.”

The remains of Mr Gregory were reburied on King William island in 2014, with a plaque marking the site.