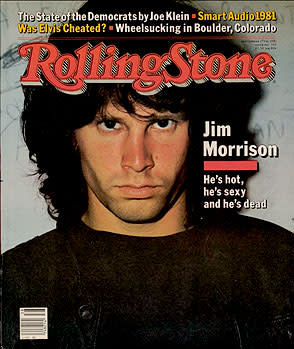

He's Hot, He's Sexy, He's Dead: Rolling Stone's 1981 Jim Morrison Cover Story

Jim Morrison, 1981: Renew My Subscription to the Resurrection

by Rosemary Breslin

Kelly's mother picked up the phone for the fifth time that night. It was for sixteen-year-old Kelly.

"Who's speaking?" the mother asked.

"Eddie," the boy answered.

"I've got it," Kelly shouted.

When Kelly hung up the phone, her mother inquired, "Who's Eddie?"

"A friend," Kelly replied.

"Where's he from?" She didn't like the sound of the accent.

"Oh, I think he's from Spain," Kelly said and slid out of the den.

Puerto Rican, the mother worried. Just what she wanted for her blond-haired, green-eyed daughter. The next day, she was cleaning Kelly's room. In a small wooden frame on the bureau was a picture of a young man. His hair was long and curly. He wore no shirt. His arms were spread out as if he were being crucified.

When Kelly arrived at her Long Island home that afternoon, her mother confronted her with the picture, "Is this the animal you're going out with?" she asked.

The 100 Greatest Singers of All Time: Jim Morrison

Kelly glanced at the picture and laughed. "Mom, that's Jim Morrison. From the Doors. A band," she said, tripping upstairs to her room. "And he's dead anyway," Kelly continued as her mother stood in the door-way, still waving the picture. Kelly was relieved that she hadn't noticed the other pictures of Morrison on her fireplace mantle.

Kelly will tell anyone who asks that her favorite group is the Doors. She even bought Eddie-from-Spain a black T-shirt with her favorite picture of Morrison on the front. Kelly can't always name any of the Doors' songs, but if you sing one, she'll know it.

Just why Kelly's into Jim Morrison is difficult to explain, but there's no doubt that she and most of her friends can recite, in great detail, the story of his life. Their talk centers on the drinking, the drugs, the performances that ended in near riots. An arrest in Las Vegas for a fight with a cop. Trouble on an airplane bound for Phoenix, resulting with Morrison in hand-cuffs. An onstage bus in New Haven for rapping about a backstage confrontation with police. And the most famous bust of all, his arrest after a show in Miami on several counts of indecent exposure and lewd and lascivious behavior. Most of these teenagers couldn't care less whether Morrison actually exposed himself or not; they simply adore the fact he would even think of doing it. The new generation of Doors fans, many of whom were in kindergarten when the band peaked in the late Sixties, is attracted to Morrison's unabashed sexiness, the lure of his voice and the hot, ornery lyrics. A song like "The End," in which Morrison, in an Oedipal rage, screams, "Father, I want to kill you/Mother, I want to fuck you," is heady stuff for a seventeen-year-old. To these kids, Morrison's mystique is simply that whatever he did, it was something they've been told is wrong. And for that they love him.

The extraordinary distance between his life, his stardom and their own youth likely fuels the worship: maybe if these kids saw Morrison today, they wouldn't be so certain all his activities were godlike. But in death, he remains their ageless hero, the biggest of them all.

"It's amazing," says Bryn Bridenthal, vice-president of public relations for Elektra/Asylum Records, the Doors' label. "The group is bigger now than when Morrison was alive. We've sold more Doors records this year than in any year since they were first released."

Video: Watch a Clip From Doors' Documentary 'When You're Strange'

The statistics are impressive. Every album in the Doors catalog, for instance, doubled or tripled its sales in 1980 over the previous year. Aided by Elektra's decision to drop the list price of The Doors, Waiting for the Sun and The Soft Parade from $8.98 to $5.98, kids all over America began scooping up the old records. In fact, of twelve Doors albums, ten have now been certified gold or platinum.

"The Doors' catalog is an amazing success," affirms Joe Smith, chairman of Elektra Records. "No group that isn't around anymore has sold that well for us."

The Morrison revival began about three years ago and has grown from a modest renaissance into a landslide. Though the roots of this posthumous popularity are not perfectly clear, music-industry executives tend to trace its origins to the 1979 release of Francis Coppola's Apocalypse Now, which prominently featured "The End." This unexpected bit of reexposure was soon followed by the appearance of An American Prayer, an album of Morrison reading his own poetry (recorded in 1971) with instrumental backing added years later by the remaining Doors. Though sales were poor, it stirred further interest in this disembodied voice, this done from the past. But the big push came with the publication of a Morrison biography. No One Here Gets Out Alive, by Daniel Sugerman and Jerry Hopkins. To date, 740,000 trade and mass-market-paper-back copies have been printed, and the book made the best-seller lists. Its last chapter, which raises numerous questions about the circumstances of Morrison's death and the disposition of his remains, is just the sort of dark, eerie, mysterious tale that tends to set impressionable minds dreaming.

Soon, FM stations were sneaking the Doors back onto their playlists. Together, the renewed airplay and the lowered LP prices had the kids buying Doors discs in sufficient quantity to put three of them on the charts again. A phenomenon was reborn.

The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time: The Doors

"It's a whole new audience," says Bob Gelms, music director of WXRT in Chicago. His station, along with many other FM rock outlets, is playing Doors songs with the frequency of many current popular bands. As Ted Edwards, music director at WCOZ in Boston, points out, many younger kids are hearing the Doors for the first time.

"The Doors sound perfect next to Van Halen," says Hugh Surratt, music director of KMET in Los Angeles. "We treat them as a very viable part of our programming. It's amazing a band like that has gone on for so long. It's as if they're still recording. It says something for their durability and for the cyclical nature of things. Everything comes back around."

Yet all this chronology, all these facts and figures pall beside the most important aspect of Morrison Resurrectus: the need today for kids — perhaps for us all — to have an idol who isn't squeaky clean. Someone rebellious, someone with a smirk that's more cynical than mean, someone whose sexiness is based on steamy eroticism, not all-American good looks. James Dean, not Shaun Cassidy; handsome with problems gets them always.

Photos: Break on Through: The Lasting Legacy of the Doors

When Gloria Stavers worked at 16 Magazine during the Sixties, she championed the Doors and once or twice even managed to slip Jim Morrison into a publication that counted as its top attractions the likes of Bobby Sherman, the Mod Squad's Michael Cole and the Monkees. "Morrison was never one of our big draws," says Stavers. But things have changed. "Now I get calls from my fourteen-year-old godson to send him pictures of Morrison," Stavers says. "A friend's sixteen-year-old daughter in the suburbs has pictures of Morrison on her wall. She's gone on Morrison and the Doors."

John Densmore, the Doors drummer, is amazed by the fact that he's asked for autographs wherever he goes these days — mainly by fifteen-year-olds far too young to have ever heard the band perform. "About three years ago, my nieces in Boston — who were about thirteen — told me that their classmates were into the Doors," says Densmore. "It isn't like it stopped for ten years, but in the last few years, it's a big business again." In fact, some of Densmore's friends have begun asking him to sign their old Doors records. As one told him: "Shit, your guys are famous again."

There has been some spillover from the younger listeners to a slightly more adult crowd, but it seems largely caused by proximity rather than taste. A trickle-up theory, you might say. "A few kids at school listen to the Doors," says one Brown University student, "but nothing like the little kids. Everywhere I go this summer, I hear the Doors. You can't help it. And my girlfriend just bought an old album; she'd never listened to them before at all."

"I think it's fifty-fifty with kids," suggests Gloria Stavers. "Half of it is their fascination with the music, half is with Jim. Talk about the living dead." Or, you might say, his identifiable, aspirational aura. The common lore about Morrison's life is full of the sorts of things that kids imagine could only have happened in the Sixties. And they wish they'd been there.

Morrison was born in 1943, the eldest of three children of a naval officer. As is common in military families, the Morrisons moved around quite a bit. Jim attended three colleges, ending up at UCLA, where he studied film. By the time he graduated, he had more verve than direction. He drifted to the beach at Venice, California, where he took a lot of drugs, slept where he could and wrote lyrics under the Pacific Coast sun. There, he ran into Ray Manzarek, a keyboard player and fellow film student at UCLA, and they discussed forming a band. Morrison told Manzarek that this wouldn't be just any band; they were going to be big. Manzarek didn't know whether to believe him or not — "Jim was just a guy like the rest of us," he says — but what the hell, there was nothing to lose. And so the Doors were born.

Within a few years, the Doors got all the success Morrison had predicted. But he soon discovered he wanted more. He became disenchanted with his Lizard King image, that of the beautiful delinquent in black-leather pants whose audience screamed for "Light My Fire" every time he bounded onstage. Morrison hadn't even written the lyrics to that trademark song; they'd come from Robby Krieger, the group's guitarist. It was the scene, the milieu of outrage, that the fans would come to witness. And Morrison ultimately rejected it, undertaking a self-destructive path, as if to mock his strange glory. He really wanted words and theater. He wanted to be recognized as a poet. Maybe he would have been, had he not quietly died in a bathtub in Paris that July night ten years ago. Of the two experimental films Morrison made, Feast of Friends was generally panned and Hwy, a movie about hitchhiking, was considered an incomplete work. Morrison's one published book of poetry, The Lords and the New Creatures, was issued in 1970 by Simon and Schuster. More than 5000 copies remain in stock.

Though Morrison's life is prehistory to Kelly and her cohorts, they discuss it with great interest. They'll talk about the Doors' songs, too, though with varying degrees of familiarity. "I really do listen to the music," Kelly said. "An old boyfriend got me into it last year. We'd listen to it at his house. The music knocks you out when you're high. Oh yeah, I know 'Light My Fire' and 'The End' best."

Kelly is also heavily into Doors paraphernalia. Buttons that cost two dollars ("We steal them from the mall"). T-shirts and denim jackets emblazoned with Morrison's face. Posters for their bedrooms. Bumper-stickers for cars they don't yet have.

Most of the girls say they love Jim Morrison, but they have no idea why. Yet when Kelly and her friends tick off the names of the other groups they listen to, it becomes clearer why they're so into Morrison.

"Oh, the Who, the Stones, Styx, REO Speedwagon," Kelly said. With the newer bands especially, most kids don't, and many can't, name an individual member; no one personality sticks out from the pack. Even when Mick Jagger's name is mentioned, it's obvious he doesn't appeal to teenage girls today like he did a decade ago. The band might be as big as ever, but Jagger isn't, and that's the point. Mick Jagger, at thirty-six, is too old for them; his nine-year-old daughter, Jade, is just a few years younger than some of Kelly's friends. Jagger himself is as old as some kids' parents. Not Morrison. The Jim Morrison the girls fall in love with, the one in the pictures, is about twenty-five and always will be.

After the attraction of a face that spells pure sex and the sultry voice that goes with it, there's the air of mystery that surrounds Morrison. "You know, nobody saw his body," Kelly said. She glanced out the window of the bus as it rolled toward the beach and then turned to her friend Harry. "I heard that Morrison might be living in Brazil. Or maybe it was in Africa."

"When I want to play games with someone's head, I tell them that Morrison might not be dead," said seventeen-year-old Harry, who was wearing a worn white T-shirt with a picture of Morrison and the words Morrison Lives! written in red.

"Yeah," added Harry, "only Pamela saw the body." To these kids, it is a great thing that nobody close to Morrison, aside from Pamela, his wife, saw the body. It makes for a very good story.

Furthermore, "Pamela O Ded three years after Jim died," Harry noted. "So now there's no one alive who saw his body."

"Harry knows everything about the Doors," Kelly said. She lowered her voice: "I broke his heart in eighth grade."

"He's probably over it," a friend said.

"I don't think so," Kelly answered, shooting a glance at Harry.

"Ray Manzarek said if anyone could pull off disappearing, Morrison could," Harry continued. After he'd carefully arranged his beach blanket, Harry took a snapshot out of his beach bag. "I took this picture of Manzarek at Rock Ages, a rock & roll flea market." Kelly grabbed the photo. It was clear from the impatient look on her face that she had no idea who the guy was.

"I have a picture of Morrison's grave at home," Kelly said. "My sister's friend, Leslie, visited it last summer."

At Pére La Chaise, one of Paris' most famed cemeteries, Leslie was looking at the graves of Edith Piaf, Oscar Wilde, Balzac and Chopin when she saw "Jim" spray-painted on a tombstone from the early 1700s. Leslie followed the arrow underneath the name to another grave, where another spray-painted arrow pointed her to the plot where Jim Morrison rests. A little past Morrison's grave was one more arrow and the words YOU PASSED IT. GO BACK.

"The graves in the background of Morrison's looked like a subway wall," said Leslie, an international law student. On one grave was a dome-shaped piece of concrete with a pair of fancy, made-up eyes and big red lips painted on it. Beneath it was written L.A. WOMAN. On another tombstone, a picture of Morrison had been spray-painted through a stencil. Another bore the legend KILL PEOPLE OVER THIRTY.

At Morrison's grave, four fans stood smoking cigarettes and reading the words on the other graves. Pills, wet from the rain, were scattered on his burial site, along with cigarette butts. So were an old pair of brown boots and empty bottles. The scene compelled Leslie to return more than once. "People came to party at Morrison's grave. From going there, I realized people were starting to trip again. And everybody could find significance in every little thing around the grave."

Leslie's friend, also a law student, went to pick up guys at Morrison's grave. "Aside from lots of Americans, she met Germans. The Germans loved Morrison. Lots of the graffiti was in German." said Leslie. "Some of it was even in Latin. She met one German guy there and they went away together.

"I thought the grave was an example of how there is an eternal flame for Jim Morrison. Most of them came only to see his grave. They didn't know that anyone else of importance was buried in Pere La Chaise. Me, I was wondering how Morrison had gotten into the place."

I saw some better pictures of Morrison's grave than the one Leslie gave me," Kelly said. "In a book of rock stars' graves." She turned and inspected her muscular legs. "I have to watch out for my hips.

"Hi, Claude," Kelly said to a boy who walked past.

"Quaaludes and beer," Claude said.

"No," Kelly said and turned away. Kelly put her unfinished Coke back into Harry's cooler. "I only smoke a little pot."

Inside the cooler were Kelly's three Cokes and forty-eight bottles of Schmidt's beer. Harry took one out of the cooler and walked over to his $200 JVC radio-cassette player. He was only playing the radio this afternoon because his batteries were almost gone and eight size-Ds cost eight dollars. Besides, "they play so much Doors on the radio, you don't even need the cassette."

"And they don't play New Wave," Kelly said of their favorite station. She scrunched her face as if she were chewing aspiring aspirin. That's about how much she likes New Wave. She'll listen to Frank Sinatra's rendition of "New York, New York," and Harry even likes Anne Murray, his religious mother's favorite. But forget New Wave. It doesn't even get a first chance with a lot of kids. Only Harry showed even a little interest in X, the band Ray Manzarek now produces.

But the kids do love rock. Last year, the Doors' Greatest Hits package sold almost a million copies. "It was basically an album that had been released already, but we remastered, remixed and cleaned it up,"says Joe Smith. All totaled, the Doors sold 2.5 million albums in 1980.

According to Ray Manzarek, the worst years for Doors record sales were 1974 through 1976. "Everything was swept away by disco. I think Saturday Night Fever sold 26 million records," Manzarek says. By comparison, the Doors catalog averaged about 100,000 a year. But, as Manzarek points out, "Disco dissipated; the Doors are still here."

Aside from buying the records, kids love merchandise, which is Danny Sugerman's department. Sugerman, coauthor of No One Here Gets Out Alive, manages Ray Manzarek's career and runs a management-public relations firm in Los Angeles. Now twenty-five, he started out handling Jim Morrison's fan mail at age thirteen. He was paid ten cents for each letter he answered. "He gave me hope. He was my hero, my friend," Sugerman says.

Addressing the recent Doors boom, Sugerman contends, "No one is selling the Doors. Business is great. We don't need to take advantage of anything." Sugerman initiated an official Doors fan club because of the demand for product, and because "we want to keep the quality and class. There's an incredible amount of bootlegging." Among the legitimate offerings, a shiny, French-design T-shirt with an airbrushed picture of the Doors. A cable-TV documentary about Morrison and the Doors will soon be aired. A live album is planned, using tapes that have surfaced of Doors performances on the Isle of Wight and in Amsterdam. And there's been persistent talk concerning a featurelength movie about Morrison. Sugerman throws out the names of David Essex, Roger Daltrey and John Travolta as among those who won't play the singer. Sugerman's already at work on a new book about Morrison — coffee-table size — with 30,000 words and lots of pictures. "He's bigger in death than in life," says Sugarman. "My dream was to manage Jim, and this is as close as I could get. I do everything with a lot of concern and responsibility. What Jim would want."

At the time of Morrison's death, his estate was estimated to be worth about $30,000. The Doors' music is owned by the three surviving Doors and the Jim Morrison estate, which is administered by Morrison's deceased wife's parents and by his own mother and father. Pamela Courson Morrison's dad is a retired high-school principal, Jim's father a retired admiral. "They buy condos and cars," Sugerman says. "Jim would have given it to Andy." Andy is Morrison's younger brother. However, Sugerman and most others associated with the band prefer not to discuss monetary matters. When asked how much in royalties is presently coming in, Sugerman says. "I don't like to talk about money."

"A promoter offered us ten or twenty grand to play in some arena. Without Jim," says John Densmore. "He didn't care who sang. Just that he could advertise the Doors. I'm worried. I'm waiting for some backlash. Will it get saturated? Is this going to turn against us?"

When "riders on the storm" came on the radio, five young boys laying on beach blankets began singing in out-of-tune voices. Only Kelly didn't know every word of the song, but she gave it her best shot. "Most girls think they're into the Doors, but all they listen to is Greatest Hits," said Harry disparagingly. He's been into the Doors for three years now, ever since he shared a room with his older brother. "My brother's in the marines now. Morrison got him through boot camp. He'd go to sleep singing Doors."

Harry listens to about three Doors albums each day. On July 4th, Harry's best friend, Jim, said that Led Zeppelin was the best rock group ever and "Stairway to Heaven" the best song. Harry has not spoken to him since. Harry's father once ventured to listen to the Doors, but he left the room after quickly deciding that Morrison was a crazy man. Harry's favorite baseball player is Jim Morrison, a third baseman for the Chicago White Sox.

Harry was seven when Jim Morrison died. He was three when "Light My Fire" reached Number One in Billboard magazine. The closest anyone he knows has come to seeing the Doors is a "tribute band" called Crystal Ship. They're just one of at least four such groups cashing in on the revival. In Detroit, there's Pendragon. In L.A., There's Strange Daze. "I just had a great time listening to Strange Daze." John Densmore says." They had every lick, every drum beat down. The singer even had some of Jim's rap down. Every note was copied exactly. They're making a living. They usually play clubs, but now I hear they're going to play a thousand seater in the valley."

Harry couldn't have picked a safer idol than Morrison. That's the greatest thing about the guy: he's not going to change. He's not going to go Christian on you. He's not going to preach against liquor and drugs. Morrison is going to stay twenty-eight and keep saying the things he always did, the things that teenagers like to hear. If Morrison's death is a hoax, which few kids actually believe, the best thing he could do is remain dead. He'd be thirty-eight now. Probably out of shape and with a burnt-out voice. For Jim Morrison, there's nothing quite like being dead to keep him popular.

With kids, Morrison hits home in a lot of ways."He was always rebellious," said Harry. "He hated school. He hated cops." What more do you need? Rebellion is a very popular word when you're growing up. Even if you've never had an encounter with a cop, at seventeen you've got to say you hate them.

"You know, Morrison could drink a quart of Jack Daniel's," said Harry. "He must have had some stomach. And drugs. He could get unbelievably wasted and still write. He was a genius. He read books."

"The lyrics are really the thing," Kelly said. "I can understand the words when I hear them. When I listen to the Stones, I can only make out a word here or there. You know how you listen to a record and you think they're saying one thing, but when you see the words on the cover, they're not what you thought? You feel really stupid. Well, I usually understand Morrison's words."

"You can listen to the words and relate to them," Harry said.

To be honest, most kids can't articulate what it is about the lyrics that they "relate" to. But that doesn't mean they ought to be written off as losers. At seventeen, it's just that you still haven't figured out a way to get what's in your brain out of your mouth. So you end up sounding a little ignorant, and everybody else talks about you as going nowhere.

"I think the kids are getting the message. I think they understand the words and the music," Ray Manzarek says. "I'm very proud of them. They're not a bunch of little idiots. All hope is not lost.

"Morrison introduced them to a bit of literature. Obviously, he was a poet. They might want to know what he read. Maybe from the popularized account of a wild poet, a crazy guy, they might go buy Jack Kerouac's On the Road or pick up William Blake. One of them might even read Nietzsche. Hope is in the kids."

Next: Jim Morrison is Alive and Well All Over the Place

Jim Morrison is Alive and Well All Over the Place

by Jerry Hopkins

The telephone operator asked, "Will you accept a collect call from Jim Morrison?"

I wasn't sure what to say. As far as I knew, Jim had been dead for years, yet this was the third such call in a couple of months. Finally, I shrugged and said what the hell, why not? It was an interesting conversation, but it wasn't Jim. At least not the Jim I remembered.

As the coauthor of Jim's biography, No One Here Gets Out Alive, I've grown used to phone calls and letters from fans who want to know if Jim is really dead. Some of the more interesting communications are from those who answer the question themselves with a resounding, if unconvincing, no. In fact, many of these people claim they are Jim Morrison. Living one's life vicariously through that of a stranger is one thing; instant reincarnation is another.

What seems amazing is just how many people are willing to believe such claims. Whenever the three surviving Doors performed after Jim's demise in Paris in 1971, their concerts would take on the feelings of a seance. Many in the audience honestly believed that Jim would appear any minute and grab the microphone. Sometimes, Ray Manzarek would fuel the fire by calling out to Jim, or announce that he knew Morrison was in the hall somewhere. And remember that single by "the Phantom"? Surely that was Jim Morrison, said the devoted.

I suppose I'm as responsible for this sort of thing as anyone. After all, the final chapter of our book, which deals with the circumstances of Morrison's death, is rather ambiguous. However, I take no credit for any of the reincarnated Lizard Kings I have met or heard from in recent years.

The first one I encountered was a beaut. He surfaced in San Francisco shortly after Jim's reported death and began cashing checks in Morrison's name. He wasn't writing bad checks, mind you; it was his money he was spending. It was just that he dressed as Jim did in his leather period, and that he told everyone he was indeed the singer.

Our conversations were unsettling. He told me he wanted to go to Paris and dig up Jim's grave to prove he wasn't there. "But you have to have permission from twelve Catholic cardinals to do that," he said. A visit to his home was more jarring. There, one end of a large room had been converted into a Morrison shrine — posters, fresh flowers, religious icons, the works.

Meanwhile, there were at least two other Jim Morrisons alive and well in Louisiana. I don't know why so many seem to have settled, or arisen from, there. Perhaps it's because the Doors' final performance as a quartet was in New Orleans, a concert at which Jim tried to beat the stage to death.

The first of these "Morrisons" wrote and published a book called The Bank of America of Louisiana. It begins with the words, "This is the story of the reappearance on earth of a dead Hollywood rock star as superhippie, disguised as a mild-minded Louisiana banker." The 200 pages of prose that followed were described accurately by one of the few book reviewers who paid it any attention as "either prenatal or post-Quaalude." Nonetheless, several thousand copies of the book were sold, largely by mail.

Another Southern-fried Jim Morrison was reportedly seen by "Donny" of Baton Rouge, who recently wrote me about an incident he says happened in 1978. A good friend of his, Larry, had high hopes of succeeding as a rock musician in those days, Donny said. But he abandoned them after meeting a man who lived in a mansion with a bunch of small, naked children.

"I remember Larry telling of one whole wall of a room with nothing but shelves of books all across it," Danny wrote. "Every one of the books was about Satan or had something to do with him. He also told me of a large chair that looked like a throne on which this man sat and watched over his nude children running around. Now, this will really freak you out. Larry stumbled onto some letters from major rock bands and artists, such as Led Zeppelin, Rush and others. Larry became frightened and decided to get the hell out of there, and fast! Today, Larry is one of the best Christians I know of. After his experience at that mansion, he decided he wanted nothing to do with becoming a rock & roll star. I guess you probably have guessed who this kindly, weird old man is — JIM MORRISON, THE LIZARD KING IN ALL HIS GLORY!"

A somewhat less likely but more bizarre Jim Morrison was introduced to me by someone claiming to be his "cosmic mate." "This is to let you know," she wrote, "that Jim Morrison is living, incognito, with his cosmic mate, Rhea, and four-year-old son, Jesse Blue James, in Staten Island. His initial rising was in May 1979. Jim has evolved into a state of pure energy and can materialize and dematerialize. Jim and I are the first human examples of cosmic mate neutralization (a mental and physical process). We are part of a Divine Plan and are under Divine Direction. Jim and I can communicate telepathically/electromagnetically. You are the first, Jerry, to hear from us. We'll get in touch with you again, soon, and give you a way to reach us (if you want to). I, Rhea, am writing this letter under Jim's direction. I am his Ambassadress-Wife."

You might give me a call, Rhea. I'm in the telephone book. But please, don't call collect.

Next: Music Without the Myth

Music Without the Myth

by Paul Williams

Pop music, in and of itself, has no meaning. We put meaning into it. The Doors never equaled their superb first album, but they did create a respectable body of work and, of course, a legend. Leaving the legend aside for a moment, the body of work can be most readily apprehended by looking at four tracks: "Light My Fire," "The End," "When the Music's Over" and "Riders on the Storm." When I was nineteen, I thought this was the greatest stuff I'd ever heard, and I see no reason why any present-day nineteen- or fifteen-year-old shouldn't feel the same enthusiasm for it.

"Strange days have found us." At the time, this seemed the perfect evocation of 1967. It may have been, and it may be perfect in 1981 as well, but it also evokes the way the world feels at a certain moment in any young life. Like so much good pop music, from "At the Hop" to "Double Dutch Bus," the Doors' opus is essentially the work of amateurs. One result is that what's good about it is fresh and actually stays fresh for decades, as long as it's heard with fresh ears.

"Light My Fire" is simple — but quite sophisticated in its simplicity. The closest thing I can think of to its instrumental build-up is the long version of the Who's "Won't Get Fooled Again." Certainly, it was an inspiration for Cream's "Spoonful," out of which grew a whole generation of British blues-rock raveups. But no one has ever made it feel so Dionysian, yet look so Apollonian, as the Doors did in this, their signature tune. The place where music and sex come together is explored effectively, thoroughly, joyously; how could such a song fail to be eternally popular with the postpuberty age group?

In its day, "The End" established Jim Morrison as something other than this band's pretty lead singer. Today, Morrison's identity is a priori established — legendary dead famous prophetic crazy man, heard about from somebody whose friend read part of the best-selling book — and "The End" is the song that fulfills the myth. It does so very well. Listened to with fresh ears, and with the knowledge that it is a creation from another place, another time, it seems no more out of date than Baudelaire or Weill. The group functions very much as a unit, and as a result, this is one of the rare instances of recorded rock theatricality that works. A mood is evoked, a soliloquy set in motion and supported, sustained, built upon and carried through. Opportunities for the listener to insert meaning are everywhere. Surely this LSD-soaked confection is as irresistible today as it was the last time we were free to take it seriously. Take your Walkman down to the river, and try not to throw yourself in.

I still like the drums, the organ, the guitar, the vocals very much. Notice how you can hear each instrument. This, plus the pseudo blackness of the themes, ties in well with the punk/New Wave current of reaction against the twenty-four-track sound. But on their successful tracks, the Doors never seem to be taking a stance (whereas they do appear to be posturing on such postsuccess failures as "Five to One" and "The Unknown Soldier"). They assume a total confidence and authority within the mysterious world of their own projection. This is comforting, emboldening, ultimately attractive. And more palatable from a mythical artifact than if attempted by a present-day band.

"When the Music's Over" still sounds best on headphones at extremely high volume — blast away confusion, frustration and loneliness, dance and shout and scream. This song, which seemed like the totality to its admirers back in the Sixties, is at best just a totality now, but there's been a lot of music over the dam since then. For the fastidious, there's probably more dignity and a better illusion of real evil or nihilism in "Gimme Shelter" or "Sister Ray" or "Holidays in the Sun." Love's "Revelation," recorded at the same time, was more outrageous and just as perfect. But just as my sentimentality, a favoring kind of prejudice, probably causes me to continue to rate "When the Music's Over" as high as I do, so also a disfavoring kind of prejudice is operating in those who disdain the song because Morrison seemed so shallow later, a pseudo-pop prince, a buffoon capable of recording empty bombast, not worthy to carry the black flag.

This prejudice for and against will continue to rage as those turned on by the reborn myth and those revolted by it continue to perceive the best and worst even in the respective worst and best of what the Doors actually achieved. Nothing special in this. Rock & roll loves contexts, loves to let its listeners wrap it up tight in meanings created of that moment and then given historical significance by memory, the second most important component of pop after immediacy (so much more important than lyrics, music or a pretty face).

Finally, "Riders on the Storm," dismissible as Muzak and different in sound from anything else the Doors recorded, washes over and touches this listener and offers enduring proof that there always was something real behind the pretense, and that the heart of it lay in the identity of the four as a group, not in the riddle of the charismatic individual. In other words, I like the music here enough to overcome my prejudice against its cocktail-piano roots, and am set free to put into it all kinds of delicious meanings. "Like a dog without a bone, an actor out on loan" sounds stupid to me, but I don't care.

By the time this song came out, I was much, much older, had almost forgotten about the Doors, and, of course, knew that my old hero and sometime acquaintance was dead. But already back in 1968, my projection had died — no chance I'd ever hear them perform "Gloria" as an all-inclusive hymn to the end and beginning of the world again. So by 1971, the sweet oceanic gentle oblivion-hawking and -mocking of "Riders on the Storm" seemed not only appropriate but positively welcome as the acknowledgment and proud banner of the romanticism that had always been the essence of our mutual pretense that none of us would make it out of the concert hall or even to the end of the record alive.

And the legend of Morrison, exaggerated as it is and always was, does not serve to distort the music. If the new Doors fans were really mere seekers of the legend, An American Prayer would be the best-selling Doors album now instead of The Doors. The myth is only a platform for and convenient introduction to the music. The relationship of the listener to the music is completely private. It has no meaning outside its own intensity. No meaning at all.

This story is from Rolling Stone issue 352.

Related

• The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time: The Doors

• The 100 Greatest Singers of All Time: Jim Morrison

• Photos: Break on Through: The Lasting Legacy of the Doors

• Video: Watch a Clip From Doors' Documentary 'When You're Strange'