A Hero’s Ending: Why Robert Redford Didn’t Strike Out

This feature originally ran in April 2015. It’s being reposted for Opening Day!

Page to Screen is a recurring column in which Matt Melis explores how either a classic or contemporary work of literature made the sometimes triumphant, often disastrous leap from prose to film. This time, he embraces the beginning of the baseball season with a comparison of book and film versions of Roy Hobbs.

“There goes Roy Hobbs, the best there ever was in the game.” – Roy Hobbs, The Natural

Literature rarely lends itself to the feel-good endings of traditional Hollywood fare. Yes, William Golding’s plane-wrecked boys do get rescued, but their innocence has been bashed like flotsam against the rocky shoreline of that island. Similarly, Harper Lee’s enigmatic Boo Radley may save Scout and Jem from Bob Ewell, but her novel’s other mockingbird, Tom Robinson, meets a bullet-riddled fate. Even when the boy does get the girl in Charles Webb’s The Graduate, the thrill of conquest fades quickly as all of life’s uncertainties await the runaways when they finally exit that bus. Simply put, Hollywood historically tends to bank on “happily ever after,” while literature – and the films that draw faithfully from it – reminds us that life is never that simple.

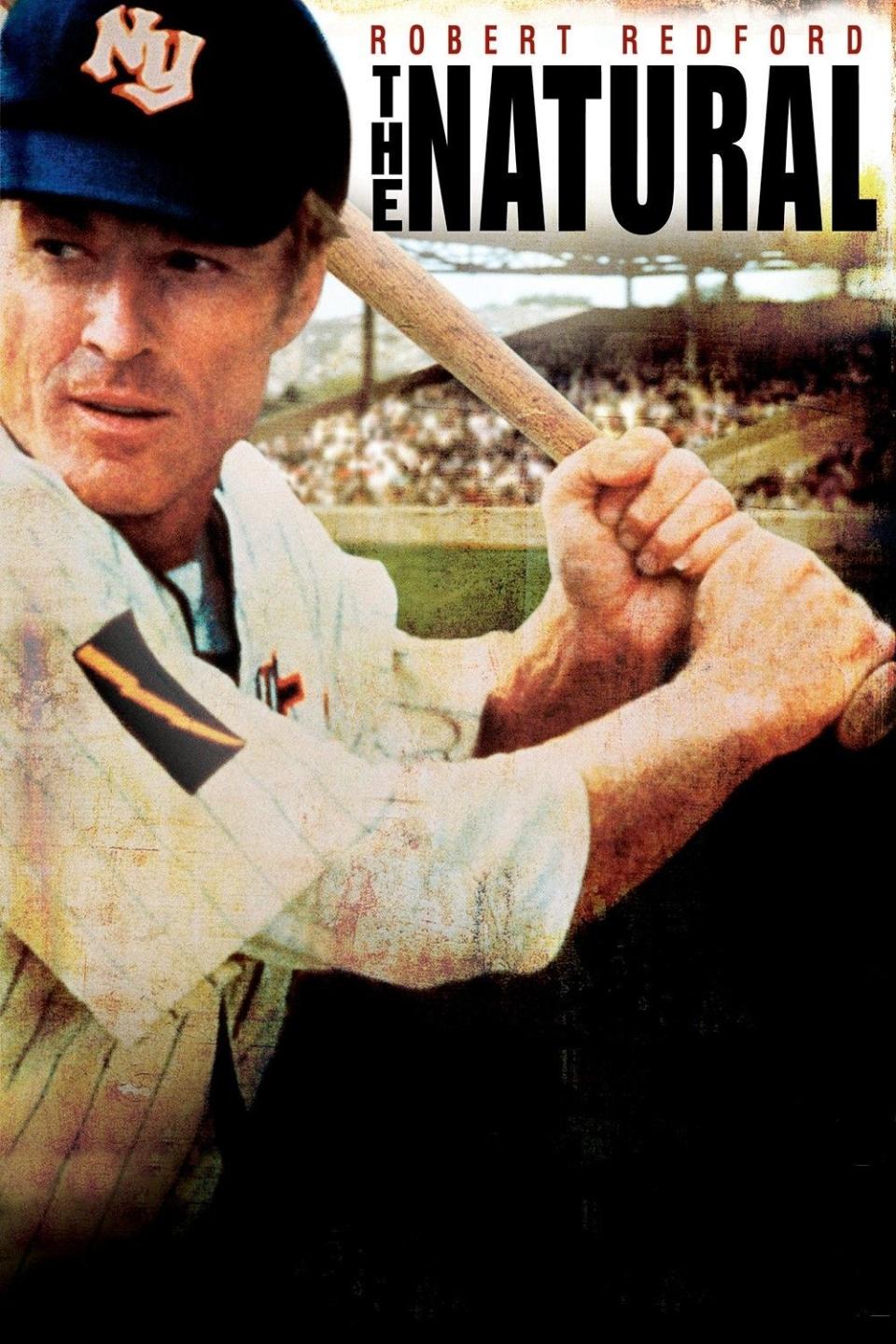

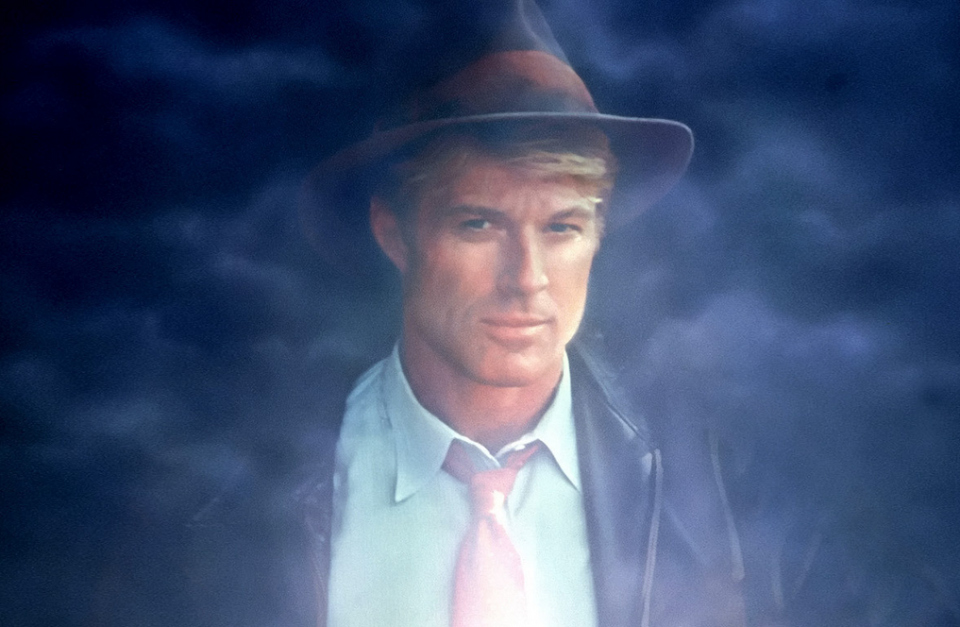

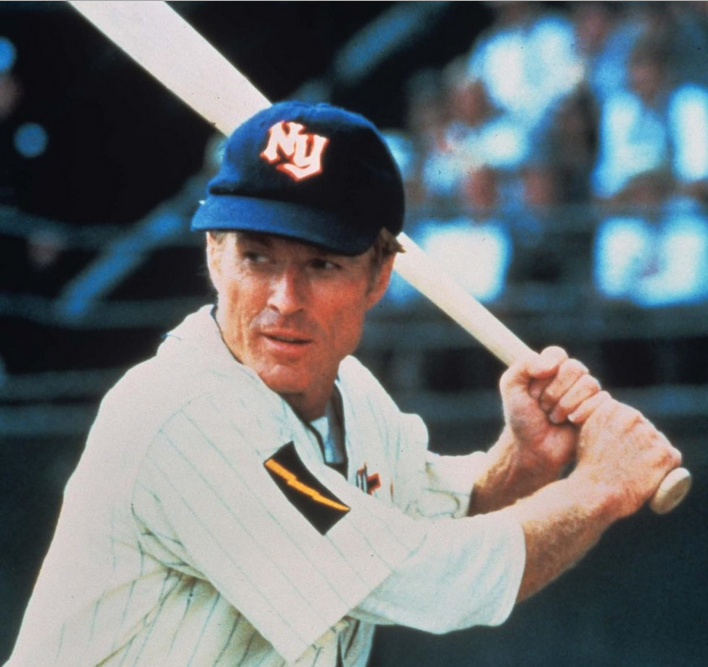

The conclusion of director Barry Levinson’s 1984 film The Natural is the epitome of a feel-good Hollywood ending. Aging and ailing superstar Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford), at the peril of his life, clouts a pennant-winning home run that shatters the grandstand lights of New York Knights Stadium and heroically trots around the bases as sparks pour down all around him like glowing baseballs. We then follow the flight of the ball to Hobbs back home on the farm, playing catch with his carbon-copy blonde son as Iris (Glenn Close), presumably now his wife, affectionately looks on. Roy smiles, finally content. In his second chance at life, he gets the glory, the girl, and the family. Any father or son watching this final scene pretends to have a bit of dust in his eye.

Bernard Malamud, author of The Natural, imagined a much different fate for Hobbs. In Malamud’s novel, the mighty home run is an equally thunderous whiff for strike three, and Hobbs, after violently confronting Judge Banner, Gus Sands, and Memo Paris, discovers his grisly past exposed in the papers alongside allegations that he threw the big game. The novel ends with Roy crying bitter tears after a paperboy inquires, “Say it ain’t true, Roy.”

Many critics of Levinson’s film, which was adapted for the screen by Roger Towne and Phil Dusenberry, cite the storybook ending as an abomination — a watering down or flat-out massacre of Malamud’s intention. Roger Ebert went so far as to call it “idolatry on behalf of Robert Redford.” Malamud’s ending undoubtedly stands as the more compelling conclusion (and more true to experience); however, I cannot imagine people lining up at the box office to see Roy Hobbs strike out and the movie end with Pop Fisher (Wilford Brimley), Red Blow (Richard Farnsworth), and Bobby Savoy huddled in tears in the dugout. No, my concern isn’t that Levinson took drastic liberties with his source material. Far more interesting is that the film veers from the book drastically enough that Roy actually earns this perfect hero’s ending.

Malamud’s The Natural leans heavily on mythology and, at times, an almost supernatural sensibility. Look no further than a few of the main players: a black-veiled siren who slays with silver bullets (Harriet Bird); a glowing demon couched in darkness who speaks forebodingly in parables and maxims (The Judge); a one-eyed soothsayer (Gus); and a magical weapon (“Wonderboy”). Levinson preserves these characters and some of the novel’s mythical aspects, but opts for a far more accessible and familiar framework for moviegoers: the father-son story.

Levinson’s Natural begins and ends with a father and son playing catch and paints Roy as always trying to fulfill his father’s dreams of him becoming a major leaguer. When manager Pop Fisher says that his mother told him to be a farmer, Roy responds: “My father wanted me to be a ballplayer.” Conversely, Malamud’s novel only mentions Roy’s father in passing. Levinson’s Hobbs also finds himself assuming various other father-son roles throughout the film. In many ways, his loyalty towards Pop, barely discernible in the novel, makes a father figure out of the weary, old skipper. And whether it be the endless camera closeups of boys in the stands when Roy comes to the plate or the way he takes bat boy Bobby Savoy (not a character in the novel) under his cannon-like arm, the slugger can frequently be seen adopting a father-like role, a disposition entirely absent in Malamud’s Hobbs. Most importantly in the film, we see Roy pool his strength when he finally learns that he has a grown son; he finds one last majestic swing because he knows his son is watching from the stands. Having largely abandoned Malamud’s complex mythology, Levinson frees himself to depict the much more relatable passage from boyhood to fatherhood.

In a way, Levinson remains far more faithful to Malamud’s antiquated ideas of women existing purely as destroyers or saviors. Both the book and film version of Harriet (Barbara Hershey), of course, aim to strike down Roy, and whether you view Memo Paris (Kim Basinger) as the film’s conflicted secret agent doing Gus’ bidding or the book’s more ambiguous destructive force eternally hung up on the late Bump Bailey, there can be no doubt that she spells trouble. In contrast, we have Roy’s prospective savior, Iris. In the novel, Malamud depicts Iris as dressed in red and having black hair, the exact opposite of Memo’s red hair and perpetually black mourning attire. Levinson even less subtly chooses to dress Iris in pure, angelic white and always lights her brightly. In either case, we’re being clearly shown that one woman offers doom and the other salvation.

However, while Iris acts as a savior type in both book and film, Levinson changes her story quite a bit. In the novel, Iris is a complete stranger who Malamud introduces at a game in Chicago during Roy’s brutal slump. She stands up in the crowd when Roy is at bat and restores his confidence. When they take a drive and go swimming after the game, Roy gets her pregnant. In the film, Iris is a high school sweetheart who Roy impregnates the evening before leaving on his doomed train ride for a tryout in Chicago. He has no contact with Iris — nor does he know about his teenage son — until their paths cross again some 16 years later. Again, giving Hobbs a grown son fits the father-son structure that Levinson relies upon, but at the same time, the director and his writers had to be concerned about the peculiar way Malamud draws Iris. After all, would a modern movie audience buy the notion of a woman supporting a stranger simply because she hates the idea of seeing a hero fail? It’s fair to guess, probably not.

In both the book and film, Iris delivers the line that goes furthest towards explaining Malamud’s strange tale. She tells the slugger, “We have two lives, Roy: the life we learn with and the life we live with after that. Suffering is what brings us toward happiness … It teaches us to want the right things.” At the most basic level, Malamud’s Hobbs can be viewed as a man who never learned what he needed to in that first life, while Levinson’s incarnation manages to live a second life that narrowly avoids the mistakes of the first — hence the hero’s ending. As it turns out, the book and the film, more than anything, are really a tale of two different Roy Hobbs.

Malamud’s Hobbs can be viewed as a tragic hero — a character who possesses a flaw that ultimately leads to his downfall. Roy’s flaw is a misguided sense of ambition, one that drives him towards greatness but never allows him to feel satisfaction. He cannot be just a great ballpayer; he must be the greatest ever. A pretty girl is not enough; he needs the most gorgeous creature in town. It’s this flaw that steers him towards Memo, a woman who leaves him weak in the knees, rather than Iris, a woman who stood up for him when nobody else dared to. His desire to have and keep Memo ultimately leads him to accept a bribe from The Judge and Gus to fix the big game — yes, Malamud’s Hobbs agrees to toss the biggest game of his life. It isn’t until Roy strikes Iris with a foul ball (talk about can’t-miss symbolism) mid-game that he learns that she is pregnant with his son and attempts to win the game. But the change in Roy comes too late to save him.

Levinson’s Hobbs is far more likable, far less chauvinistic, comfortably assumes father and son roles, and strikes us as someone who continues to suffer for a single mistake he made as a teen. “Some mistakes I guess we never stop paying for,” Roy tells Iris from his hospital bed. This isn’t a character we wish additional suffering upon. What’s more, he has grown wiser from that ghastly hotel encounter with Harriet Bird 16 years ago. Drawn as he may be to the alluring Memo, he recognizes her as a destroyer, another Harriet, before it’s too late. And due to Roy’s pure love for baseball and the internal promises he’s made to his own father and Pop, as well as the responsibilities he feels towards his young fans, he turns down the bribe and plays to win from the first pitch. So, when Roy Hobbs takes to the plate in that final at bat of the film, instead of the burden of his poor choices causing the sweet spot of his bat to drag through the hitting zone, we find an ill man — now knowingly a father — who has earned a moment of redemption, a chance to trot off into the proverbial sunset touching four last bases as he goes.

Clearly, the feel-good ending isn’t everyone’s cup of crackerjack. It’s all too perfect, but again, we’re in the realm of movies and not literature at this point. As Wonderboy surrogate the Savoy Special delivers that final blow, our hero glides around the base paths, and the fireworks and film score strike up, there’s only one thing left to say: Welcome to Hollywood, Mr. Hobbs.