After Her Debilitating Stroke, Tatum O’Neal Attempts to Heal a Fractured Relationship With Dad Ryan O’Neal

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Fifty years ago, a novice child actress named Tatum O’Neal captivated the world in Paper Moon, the Great Depression-set classic about a motherless little girl (O’Neal) and a grifter — possibly her father (played by her actual father, Ryan O’Neal) — tasked with transporting her from Kansas to an aunt in Missouri.

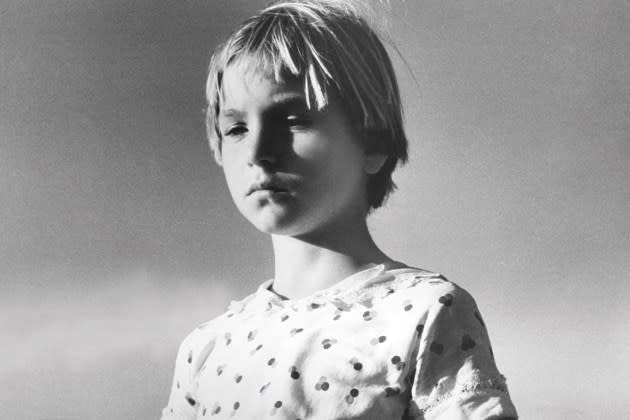

Her performance — funny, heartbreaking, assured beyond her years — won 10-year-old Tatum an Oscar for best supporting actress at the 1974 Academy Awards. Styled adorably in a tuxedo and tomboy haircut, a stunned Tatum — who was chaperoned by her grandfather (Ryan was overseas making Barry Lyndon with Stanley Kubrick at the time; her mother, ’60s TV actress Joanna Moore, was long absent, having succumbed to amphetamine addiction) — told the audience at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion: “All I really want to thank is my director, Peter Bogdanovich, and my father. Thank you.” A half-century later, she still holds the record for youngest Oscar winner.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Box Office: 'Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom' Starts With Sluggish $4.5M in Thursday Previews

Fox Pulled John Schneider Press Interviews Over Joe Biden Tweet After 'Masked Singer' Exit

'Anyone But You' Review: Sydney Sweeney and Glen Powell Can't Fake the Fizz in Strained Rom-Com

It was the stuff of Hollywood fairy tales. What ensued, however, was anything but. As chronicled on the covers of countless celebrity glossies and talk shows, in gossip columns and in tell-alls, Tatum’s journey since winning her Oscar has been one steeped in pain, loss, addiction — and an eternal need to repair her tortured relationship with her father.

By his own admission, Ryan was never up to the job. “I had this peculiar thing on Paper Moon, and that is the director insisted she wasn’t my daughter,” he said on Ryan and Tatum: The O’Neals, a 2011 OWN reality series that documented a failed attempt at reconciliation. “The director insisted that my character, Moses, never thought for a second that this was his daughter. So he wanted me to make sure that I didn’t think of her as my daughter. And maybe it never wore off.”

Tatum summons me in late March, through a mutual friend. In two days, she once again will reunite with her father, whom she hasn’t seen in years. But this time things would be very different. In May 2020, Tatum O’Neal suffered a massive stroke caused by a prescription drug overdose. The stroke left her in a coma. When she finally reawakened a month and a half later, she couldn’t remember how to speak. Every day since then has been a struggle to relearn everything, from square one. And she’s doing it. Little by little, day by day.

***

Tatum, 59, greets me with an apology. “I gained some weight. I vape. I didn’t try to make myself look pretty. I didn’t do anything,” she says. She stands out among the other residents of her current home — an upscale retirement community in the San Fernando Valley specializing in memory care. The vast majority of her neighbors are decades older than she is. She spends hours every morning in speech and memory therapy and has made miraculous strides already, capable of conversing for hours at a time, if frequently fumbling for a word. (A friend who is gay, for example, becomes “a man who loves other men.”) There were fears she might never walk again. Luckily, the stroke did not greatly affect her mobility, which already was suffering as a result of rheumatoid arthritis. She gets around on her own two feet, albeit with a limp.

O’Neal occupies a studio apartment on the second floor of the property and spends her days in a comfy chair, one leg propped on an ottoman to ease the pain of her arthritis. Her reading and writing capabilities have been severely limited since the stroke. She passes the time thumbing through her Instagram feed, filled with moments from an extraordinary life. A date night with Michael Jackson, who was disguised in a fake beard. A clip from a 1975 appearance on the variety show Cher (“When I grow another five inches and lose 10 pounds, Cher’s going to be in big trouble!” young Tatum jokes). Perched on a nearby shelf is a vintage Cremo cigar box — the kind she clutches in Paper Moon.

The stroke occurred amid the terrifying first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. O’Neal was living on a high floor of a Century City apartment tower and suffering from suicidal ideations. “I kept on wanting to fall off [the building] and die,” she recalls. She then came down with a terrible flu. “I had never been so sick. I didn’t know I had COVID.” Her condition grew so grave, she gave her beloved dog Pickle over to her daughter’s care. And then, she says, she took pills — too many pills. Painkillers, opiates and morphine. “I’ve had problems with drugs for many, many years,” O’Neal says. “But I overtook my medicine, for sure. And that’s it. I fell asleep. That’s what happened.”

She was discovered unconscious by a friend and rushed to a hospital. The stroke affected her right frontal cortex. “She also had a cardiac arrest and a number of seizures,” her eldest son, Kevin, recently told People. “There were times we didn’t think she was going to survive.” After six long weeks, O’Neal’s eyes reopened, but she was incapable of speaking. Her daughter stood vigil behind a glass partition outside her mother’s hospital room. “We would talk. But I didn’t have any…” O’Neal trails off. “I still don’t have the words for everything,” she says.

The family placed her in Silverado, another assisted living facility an hour away from this one. “I was there for about three months. COVID was everywhere. And I just wanted to leave again. I was so unhappy. I didn’t have the right words. I was in that gnarly coma. I didn’t know what to say, but I wanted to leave.” One evening, a nurse noticed that O’Neal was not in her room. She was later discovered by a security guard, limping down the road about a half of a mile from Silverado. The news, alarming as it was, somehow comforted her children. Her rebellious spirit was still intact. Somewhere inside, their mother was still there.

***

Two dresses hang on O’Neal’s window — her options for her coming rendezvous with her father. “I haven’t seen my dad in three years,” she says. “I’m going to see my dad in Malibu with my daughter and her boyfriend Tim.”

That Malibu home is the same one her father has occupied since the late 1960s. It’s the same house he shared on and off with his great love, Farrah Fawcett, who succumbed to cancer in 2009, sending him into a tailspin of grief and despair. And it’s the same spot where, in 1972, Tatum and Bogdanovich took off on a stroll down the beach — on what she didn’t realize was her Paper Moon audition.

“He loved me, but then hated me, because I won the Academy Award,” she says of her father, now 82. Her father did send Tatum a note of congratulations on her win; her mother, however, never acknowledged it at all. “Weird shit happened. It kind of went in the wrong direction to happiness,” she says. Ryan O’Neal did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

The last time she saw her father, in September 2020, she had only recently begun to emerge from her stroke ordeal and was still unable to speak. Her three children from her marriage to John McEnroe — Kevin, 37, Sean, 35, and Emily, 32 — had reunited in Los Angeles to tend to their mother. As the California wildfires raged in the distance, Sean arranged the meeting with their grandfather, whom they hadn’t seen in 17 years. Sean posted a photo commemorating the moment on his Instagram. In it, Kevin is seated in his mother’s wheelchair, Emily wraps a reassuring arm around her and Tatum extends one tattooed arm to touch her father’s hand, a cane resting against his lap.

“This is one of the most memorable photos of my life,” read Sean’s caption. “The last time we were all together was at the 30-year Paper Moon Anniversary in 2003. I could cry tears of gratitude that everyone in this photo is still alive and that we were all able to come together again after so many years of hardship. The entire West Coast is burning, but if the O’Neals can reconcile, truly anything is possible.” The photo made headlines, but Tatum’s condition was kept confidential.

This time, it was Tatum who initiated contact with her father. She needed to see him again, partly because she could speak again and also because Ryan had lost his brother in January — Tatum’s uncle Kevin O’Neal, a part-time actor. His son, Garrett O’Neal, also would be on hand for the reunion.

“My father and I are going to have a conversation,” she says. “We’re just going to talk. I hope it will work out. We’ll see. I pray that it will.”

“What are you hoping comes out of it?” I ask.

“I think he’s gotten a little bit better in his life,” she replies, peering out her window at a nursing station across the courtyard. “I mean, he’s an amazing man, my dad, and I miss him terribly.”

“Have you finally forgiven him?”

“I don’t want him to die,” she says. “I love him. I love my dad. I mean, I’ve had a hard life with my dad — but I still love him.”

***

O’Neal’s mother was a beautiful B-movie and television actress on shows like The Andy Griffith Show and Wild Wild West. In 1962, Moore met a handsome 21-year-old boxer and stuntman named Charles Patrick Ryan O’Neal. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he was the son of an actress and a screenwriter who groomed him for a life in show business. He also was seven years Moore’s junior. Sparks flew, and Moore very quickly became pregnant with Tatum. They married on April 3, 1964; Tatum was born Nov. 5; 11 months later came her little brother, Griffin.

In 1964, Ryan was cast alongside Mia Farrow (“I was obsessed with her,” Tatum recalls) on the ABC primetime soap Peyton Place. Her father’s career caught fire as Moore, who suffered from alcohol and amphetamine addiction, saw hers decline. The couple fought — loudly, angrily, bitterly. They divorced in February 1967 and Moore took the kids. But her addiction then spiraled out of control. “She had virtually abandoned me and Griffin, leaving us in squalor,” O’Neal wrote in her 2001 memoir, A Paper Life. “Starving, shoeless and ragged, as well as beaten and abused by the men in her life.”

Looking back on that nightmarish period, O’Neal is amazed she and her brother survived at all. “My mother was on stuff all the time,” she says. “I could see it bad — with her teeth and all that stuff. She got mean — really, really mean — as a drug addict. I felt like I was in this old, scary movie. It was just unbelievable.”

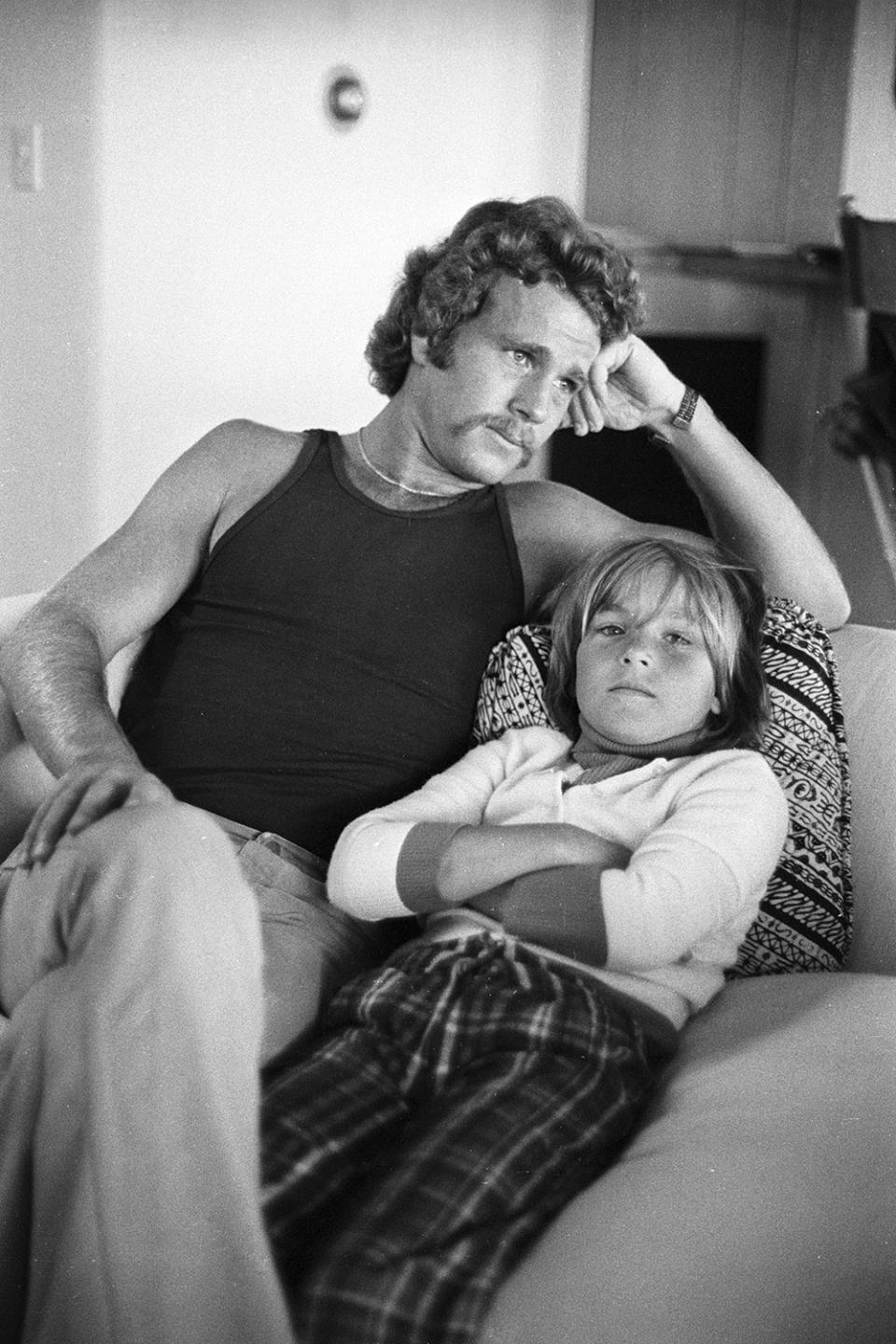

In 1970, Ryan won back custody of his children, and Tatum, then 6, and Griffin, 5, moved in with him in Malibu. It would be the same year he made the leap to movie stardom, appearing opposite Ali MacGraw in Love Story, a massive hit for Paramount that earned him a best actor Oscar nomination. “I was so excited to be in Malibu,” Tatum recalls. “I would go swimming and see friends and have fun. I was just so happy to be out of that other place with my mother.”

Ryan wrapped filming on Bogdanovich’s screwball comedy What’s Up, Doc? with Barbra Streisand, which would become the third-highest-grossing film of 1972. Movie exhibitors voted him the second-biggest box office star of 1973, behind Clint Eastwood. Paper Moon was an adaptation of the 1971 Joe David Brown novel Addie Pray. John Huston had envisioned it as a potential starring vehicle for Paul Newman and his daughter Nell Potts, but made The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean with Newman instead.

Bogdanovich’s former wife, production designer Polly Platt, recommended Brown’s book. He liked the world, but Bogdanovich wasn’t happy with the title and kept a list of alternatives, including one he’d jotted down while listening to the 1932 jazz standard “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” (His mentor, Orson Welles, urged him to rename the film Paper Moon.) But it was Platt, once again, who suggested that 8-year-old Tatum — who’d never acted before — might make a good Addie.

“I was in Malibu with Peter Bogdanovich, and we were just walking,” Tatum recalls of the directing great who died in 2022. “Walking and talking. Just on the beach hanging out. It was like, ‘Hey. What’s going on? What are you thinking?’ I was like, ‘What are you thinking? I’m just OK.’ You know what I mean? I was just glad I was still alive, that a bunch of crazy people on drugs weren’t all around me. So he said, ‘Fine. You’re done.’ I was like, ‘What happened?’ It was sort of like that.”

He never asked you to read any lines?

“Not at all,” she says. “When we started filming, it got pretty hard. People had to help me with the words.”

One of the most beloved sequences in the film is a single-take argument between Moses and Addie about Bibles — pushing the Good Book on widows is their hustle — as they drive along a mile-long stretch of road.

Bogdanovich was determined to do the scene with no cuts. “We did it 25 times the first day,” the director said in 2017. “We would get 10 lines or five lines into it and Tatum would fuck it up and we’d have to go all the way to the turnaround and come back. Ryan said, ‘I did 5,000 episodes of Peyton Place, but I’m gonna go crazy! I want to kill her!’ ”

O’Neal recalls filming the scene. “My father was like, ‘You were supposed to say this.’ And I was like, ‘Oops. Sorry.’ And then we had to drive all the way back. I remember my dad getting really mad at me. Not really mad, but sort of mad. But I love that scene, the Bible scene. I do.”

***

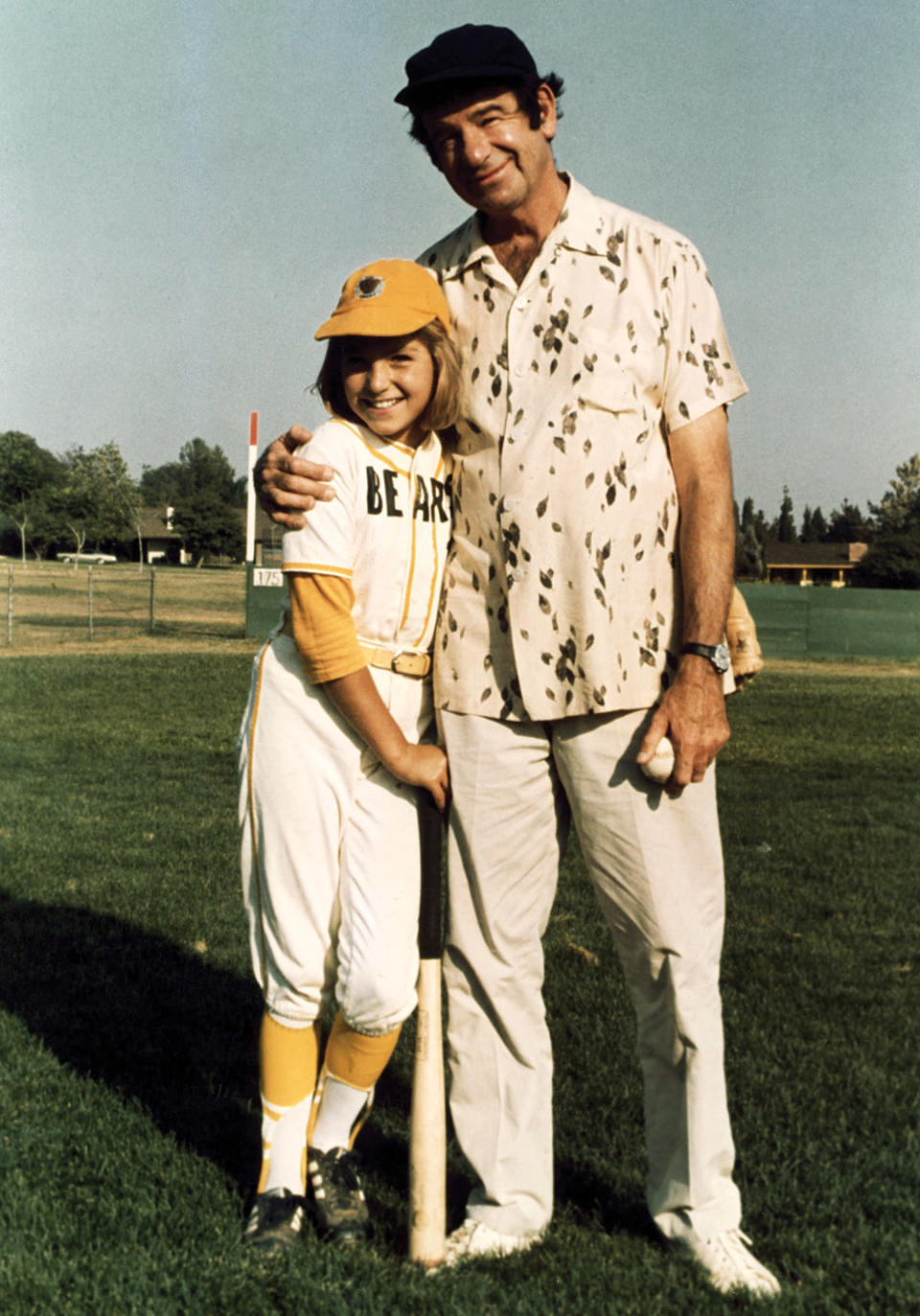

Tatum was no one-hit wonder. She followed Paper Moon with a comedy sleeper, 1976’s The Bad News Bears, in which she starred opposite Walter Matthau. In 1980, she appeared alongside Kristy McNichol — Hollywood’s other tomboy teen queen — in the summer camp sex comedy Little Darlings. (“The bet is on: Whoever loses her virginity first — wins,” read the poster tagline.)

All the while, she was set adrift in Hollywood with virtually no guidance or guidelines.

In A Paper Life — a scathing autobiography that her father repeatedly has discredited — she writes, “I remained Ryan’s companion on the Hollywood party circuit, growing inured to sex and drugs before I was in my teens.” She claims in the book that at age 12, she walked in on her father in bed with her best friend — 18-year-old Melanie Griffith, whom she met at the Playboy Mansion — and that her father invited her to sleep in the same bed with them. “I often did sleep in my father’s bed, even when he had women over,” she writes.

The book also chronicles O’Neal’s claims of multiple incidents of sexual abuse, including once at the hands of a good friend of her father; her father’s explosive temper and instances of verbal and physical abuse committed by him against both Griffin and herself; and losing custody of her own children to McEnroe after spiraling into cocaine and heroin addiction after their sensational 1994 divorce. “It felt like open season on me, on her, and especially on the two of us together,” the mercurial tennis star writes in his 2002 autobiography, You Cannot Be Serious. “Suddenly, wherever I went, it felt like a spectacle.”

For O’Neal, the wounds of that chapter have not yet healed. They likely never will. “He was very mean to me,” she says of McEnroe. “Really, really, really mean to me. Like the meanest man I’ve ever loved — besides my dad.”

In his book, McEnroe says, “It was very confusing — in our way, we were both trying to be good parents and good partners to each other, but her career was in [remission] and mine was in decline, and you need to feel reasonably good about yourself before you can be kind.”

“Do you think it’s a coincidence that you went from your dad to someone like John?” I ask.

“I think it’s a very similar situation,” she replies. “I did love being with my ex-husband. I did. But then I wanted to leave, and he didn’t want me to leave. And then when he found out that I did leave, he really hurt me in a really crazy way. In a way that I couldn’t even describe — it was awful, awful, awful. It really kicked in my drug problem in a huge way.”

Yet even in her addiction haze, when it became clear her mother was losing her battle with lung cancer, O’Neal showed up at her bedside in the Coachella Valley enclave of Indian Wells in 1997 and stayed there until her death. Not surprisingly, as she spun out into the throes of addiction and revolving-door recovery attempts, O’Neal’s acting career suffered. Like her mother before her, first came the B movies, then TV guest appearances — most memorably in a 2003 episode of Sex and the City in which her character forces Carrie Bradshaw to remove her Manolo Blahniks at a baby shower — which eventually trickled down to nothing.

“It’s been hard,” O’Neal says. “I’ve had a hard time with a lot of things. I’ve had a very hard life. Not an easy life. There’s been some amazing things and some really scary things.”

***

Five days after our first meeting, O’Neal summons me once again.

“It went really well,” she tells me. “He was really sad. Sad about his brother.”

She shows me a photo on her phone: Ryan and Tatum seated on his bed, beneath an Andy Warhol portrait of Fawcett — the same portrait Ryan won custody of in court in 2013 after the University of Texas claimed Fawcett had left it to the school in her will. They are both smiling, beaming. A frizzy lapdog is tucked beneath her arm.

“He still has a full head of hair,” I note.

“He doesn’t dye it. He has good hair. But he’s lost a lot of weight.”

“So what did you and your father talk about?”

“Not a lot,” she says. “But there was happiness. I saw he was having coffee, and I said, ‘I want some coffee.’ He was asking me things about me, and I said, ‘I have a bad back. But I’m trying so hard. I’m alive.’ But then when I tried to text him two days ago to see if I could go back, he didn’t call me back. So then it gets a little weird, unfortunately,” she says.

Three weeks later, on April 21 — her father’s 82nd birthday — Tatum posted the photo to Instagram.

“Happy birthday dad I love you,” the caption read.

This story first appeared in the July 14 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Eight Actors Who Have Played Willy Wonka in Films and on Broadway

Martin Scorsese’s 10 Best Movies Ranked, Including 'Killers of the Flower Moon'