“How the Hell Can Walt Run a Studio Without Us?”: Behind the Disney Animation Revolt of 1941

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

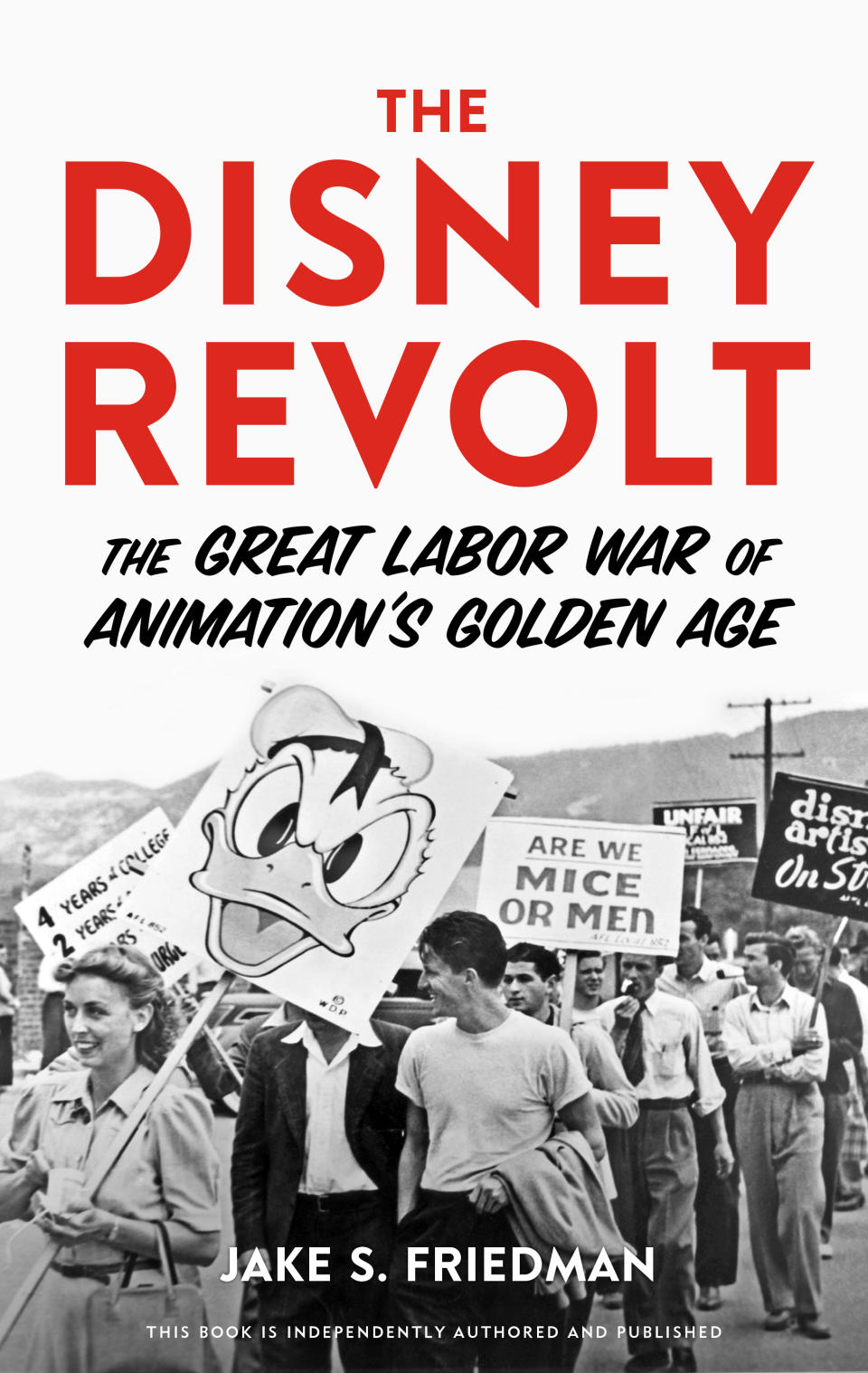

Soon after the birth of Mickey Mouse, one animator raised Walt Disney Productions far beyond Walt’s expectations. That animator also led a union war that almost destroyed the company. Art Babbitt worked for the Disney studio throughout the 1930s and up to 1941, years in which he and Walt were driven to elevate animation as an art form, as seen in Snow White, Pinocchio, and Fantasia. But as America emerged from the Great Depression, labor unions spread across Hollywood. Disney fought the unions while Babbitt embraced them. Soon, angry Disney cartoon characters graced picket signs as hundreds of artists went out on strike…

The press called them “Loyalists.” But there were many reasons why hundreds of nonstriking Disney artists drove to work the morning of May 28, 1941. Dumbo and Bambi would not be completed without them. They also shared a gratitude toward Walt, who not only hired them during the Depression but also provided them with an opulent new studio. Besides, what kind of tyrant insisted on being addressed by his first name?

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Ten Years After the SAG-AFTRA Merger: Lessons for the Union's Future

"TV - That's Where Movies Go When They Die": Rewatching the First Televised Oscars

How the Great Depression Reshaped Hollywood Studios' Ties With Workers

The first thing they noticed was a seemingly endless line of cars parked by the curb leading to the studio. What they saw at the Disney gate was a spectacle they had not anticipated.

About five hundred men and women were on their feet, walking in a large circle in front of the entrance. Nearly one in ten carried a wooden picket sign, all painted with cartoon characters.

“It’s Not Cricket to Pass a Picket,” warned Jiminy Cricket.

“I’d Rather Be a Dog Than a Scab,” chided Pluto.

“I Sign Your Drawings / You Sign Your Lives,” taunted a caricature of Walt.

“Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Rubens, Rembrandt All Belonged to Guilds.”

The number 600 showed up a few times, too, referring to the number of total artists. A strike handout reported that one sign read, “One Genius Against 600 Guinea Pigs.” Another had, “Snow White and the 600 Dwarfs.”

Traffic entering the studio slowed to a crawl. As each car inched through, the strikers hooted and hollered, calling each strike-breaker a “scab” and a “fink.” A sound truck was parked nearby, providing a portable PA system to the person at the microphone. Bystanders and non-strikers were handed flyers titled “An Appeal to Reason” — its title borrowed from the Socialist periodical that Walt’s father used to read.

“The salaries of the Disney artists average less than those of house painters,” read a press bulletin. “The Disney girl inkers and painters receive between $16 and $20 a week. On Snow White, the much-publicized bonuses did not even compensate the artists for the two years of overtime they worked. Snow White made the highest box office gross in history—over $10,000,000.00. All the other major cartoon studios in Hollywood have Screen Cartoon Guild contracts. The Disney Studio is the only non-union studio in Hollywood.” The union demanded a 10 percent wage increase across the board, a 25 percent wage increase for the lower bracketed artists, and the reinstatement of the nineteen animators who they argued were fired for union activity—including Babbitt.

The Disney carpenters, machinists, teamsters, and culinary workers refused to cross the picket line. Electricians, cameramen, sound men, and film editors also refused. One striker photographed each “scab” who drove through. Atop a hill in the eucalyptus knoll across the street, a striker in a beret and smock stood at an easel painting a landscape of the ordeal. On the ground, there were “guys pouring their individual speeches into the ears of those on the fence,” wrote one non-striker that day. “I was struck with the magnitude of it all.”

“The average age was less than 25,” said Herb Sorrell in 1948. “They became the most enthusiastic strikers I have ever seen in my life.” Some strikers leaped atop the car bumpers; other rocked the cars side to side. Once through the gates, the cars were greeted by the nonstriking inkers and painters clapping and cheering — a welcoming committee.

The strikers had each been given two- or three-hour shifts, ensuring a twenty-four-hour picket line. They were mostly comprised of inbetweeners, animation assistants, inkers, and painters, but among them were also story artists, effects artists, background painters, and animators. Bill Tytla and Art Babbitt stood out as the highest paid on strike.

The previous night, the Guild voted to include supervising animators among its membership. This made not only Babbitt and Tytla eligible to strike but also all other top animators. Babbitt was on his feet rallying alongside the other strikers, shouting to non-strikers by name, including Ward Kimball. “I felt terrible,” Kimball journaled that day. “Friends on the inside waving to me to come in. Friends on the outside pleading with me to stay out; Jeezus. I was on the spot!”

Inside the studio, the loyalists were worried. “How the hell can Walt run a studio without us?” asked Norm Ferguson. On their way inside, the strikers warned them that once the union won, it would fine them the amount equal to their salary, plus $5 per day, plus a $100 penalty. Ferguson told his fellow non-strikers, “Any agreement made will have to involve protection for you guys or Walt wouldn’t sign, so stay on and receive your salary!” With nearly all the assistants and inbetweeners outside, the animators pitched in to do those jobs for each other. If the films weren’t completed, the Bank of America might foreclose. Right now, everything was riding on Dumbo, the studio’s B picture.

Relationships were severed. It was the end of Babbitt’s friendships with nonstriking animators Les Clark and Fred Moore. He was also dating a blonde secretary named Nora Cochran before the strike; she unsympathetically stayed in.

The strike took its toll on those who couldn’t choose a side. Novice animator Walt Kelly (future creator of the comic strip Pogo) had friends on both sides, and he packed up and left altogether. He claimed it was to care for his ill sister, but privately he left his friends this note:

For years I have reached for the moon

But the business now is in roon

So I don’t hesitate

To state that my fate

Is to take a fug of a scroon!

After 10:00 am, the strikers dispersed to the adjacent eucalyptus knoll. Sorrell recalled that “from 10 to 11 or 11:30, we would talk to them on a loud speaker system, and of course they could hear in Disney’s what we were saying across the street.”

Every emphatic slur and enthusiastic cheer that erupted from the PA system echoed in the Burbank studio. Yet, Walt was seen smiling at lunchtime. “I’m going to see this to the end,” he said. “I told ’em I’m willing to hold an election, but they refuse, it’s their funeral!”

Chicago Review Press

Jake S. Friedman is an author and animation historian. This article is edited and excerpted from Friedman’s The Disney Revolt: The Great Labor War of Animation’s Golden Age (Chicago Review Press, July 5), which uses never-before-seen research from previously lost records, including conversation transcripts from within the studio walls to illuminate the labor dispute that changed animation.