‘His head swelled up to about five times normal size’: The horrific car crash that almost killed Stevie Wonder, 50 years on

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Well, pardon my French but who the hell is Stevie Wonder?” asked veteran crime reporter Ralph Miller, when a police contact rang on the afternoon of 6 August 1973 with a tip-off that 23-year-old musician Wonder was in a coma at the local Rowan Memorial Hospital in North Carolina. Wonder was fighting for his life after a horrific crash on Interstate 85.

It didn’t take long for Miller and the staff at the hospital to realise they had a superstar in their care. The Jackson 5, who, by happenstance, were due to play a gig in North Carolina the following day, offered their private jet for any necessary hospital transfers. Nurses were besieged by the media and took calls and telegrams from around the world, including from Paul McCartney and Roberta Flack. Everyone wanted an update on the condition of the man who had taken the pop charts by storm that year with global hits “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” and “Superstition”.

Wonder’s crash happened 50 years ago today. It was a momentous day for the future of music, with Wonder happily escaping death on the roads – a fate that ended the lives of so many great musicians, including Bessie Smith, Duane Allman and Marc Bolan. It was a sultry, dry Monday afternoon, just three days after the release of his magnificent album Innervisions; Wonder had performed at a concert in Greenville, South Carolina, the night before. The singer-songwriter, who had been blind since birth, was in the passenger seat of a 1973 Mercury Monarch sedan, a rental car from Hertz, driven by his 24-year-old cousin John Wesley Harris. They were on the way to do a benefit gig for WAFR – America’s first public, community-based Black radio station – in Durham, North Carolina, when the crash happened near Salisbury.

Wonder – who was born Stevland Hardaway Judkins on 13 May 1950, in Saginaw, Michigan, and whose stage name was given to him by Motown boss Berry Gordy – was asleep, having dozed off while listening to a two-track mix of Innervisions on his headphones. Harris, distracted, failed to notice a Dodge flatbed farm truck ahead, driven by 23-year-old Charlie Shepherd, and the two vehicles collided.

One myth that took hold was that a giant pine log had crashed through the windshield of the Mercury and smashed into Wonder’s head. This version was repeated by Wonder’s mother in her 2002 biography Blind Faith: The Miraculous Journey of Lula Hardaway. “There was a great, grinding screech as metal hit metal and, then, impossibly, as if in some lavishly produced Hollywood action movie, one of the great logs disencumbered itself of the truck and came crashing through the windshield, spearing Stevie square in the forehead,” she claimed.

Three years later, when Variety magazine reported on Wonder’s $1.5m (£1.2m) civil suit over the near-fatal crash, the musician’s evidence included an account detailing how the bed of Shepherd’s truck had careered through the windshield and hit him on the forehead with “great force”. The impact left him unconscious and bleeding profusely from a head wound. Shepherd’s truck then overturned, leaving the rural worker with two broken ankles and a severed upper lip.

Lula’s account doesn’t square with the fact that Shepherd had already delivered his load of logs to a town called China Grove, just south of Salisbury, well before the collision. The images taken at the crash scene by Salisbury Post photographer Bob Bailey, and notes from highway patrol trooper Don Moran, show that the truck was carrying only small pieces of wood and broken boards.

Members of the band, who were travelling in cars behind, rushed the unresponsive singer to the nearest hospital. Shepherd, who went later by ambulance, was placed next to Wonder in the hospital’s emergency room. Shepherd had no idea of Wonder’s fame, and neither did assistant nursing director DJ Whitfield, nor surgeon Dr Harold H Newman Jr, who later told his awestruck family, “I had to sew him up.”

Wonder’s head injuries were sufficiently grave for him to be transferred that evening to the intensive care unit at North Carolina Baptist Hospital, 40 miles away in Winston-Salem. Courtland Davis, president of the Neurological Society of America, performed “life-saving surgery” on Wonder, treating a “bruise on the brain”. Davis was shocked by the incessant requests for comments and medical updates from the world’s media. After he died, aged 97, in October 2018, his daughter Jean Kutzschbach told the Winston-Salem Journal: “I remember the phone ringing off the wall at home. Not long ago we were talking about that experience, and Dad just chuckled and said, ‘I was so glad when Stevie recovered enough to where he could go back to LA, where they knew how to handle the publicity.’”

Friends and colleagues who visited Wonder were shocked by his appearance in intensive care. Ira Tucker Jr, Wonder’s chief of staff, told Esquire magazine in April 1974: “When I got to the hospital... man, I couldn’t even recognise him. His head was swollen up to about five times normal size. And nobody could get through to him.”

Stevie Wonder told doctors to leave one scar on the right side of his forehead, as a reminder of what he had been through

Tucker was convinced that the power of music had brought Wonder back from the brink. “I knew that he likes to listen to music really loud, and I thought maybe if I shouted in his ear it might reach him. The doctor told me to go ahead and try, it couldn’t hurt,” he recalled. “The first time I didn’t get any response, but the next day I went back and I got right down in his ear and sang ‘Higher Ground’. His hand was resting on my arm, and after a while his fingers started going in time with the song. I said, ‘Yeah! Yeeaah! This dude is gonna make it!’”

Wonder spent two weeks in Winston-Salem. He befriended a hospital security guard named Larry Woolard, and later attended his wedding. When doctors suggested plastic surgery to remove the marks left by the crash, Wonder told them to leave the scar on the right side of his forehead as a reminder of what he had been through.

Wonder left Winston-Salem on 20 August to convalesce at a medical centre in Los Angeles. He had lost his sense of smell and taste and was still on strong medication. For the next year, he would suffer from severe headaches and fatigue. Tucker was again a motivating force in his recovery. Wonder was a talented multi-instrumentalist – as well as providing vocals, he had performed on Fender Rhodes electric piano, drums, Moog bass, synthesiser and Clavinet on Innervisions – and was deeply worried that he would not be able to play his instruments again. Tucker took a Clavinet to the medical centre and recalled the musician’s “panic” as he looked at the instrument. “Finally, he touched it – man, you could only see happiness spread over him. I will never forget it,” said Tucker.

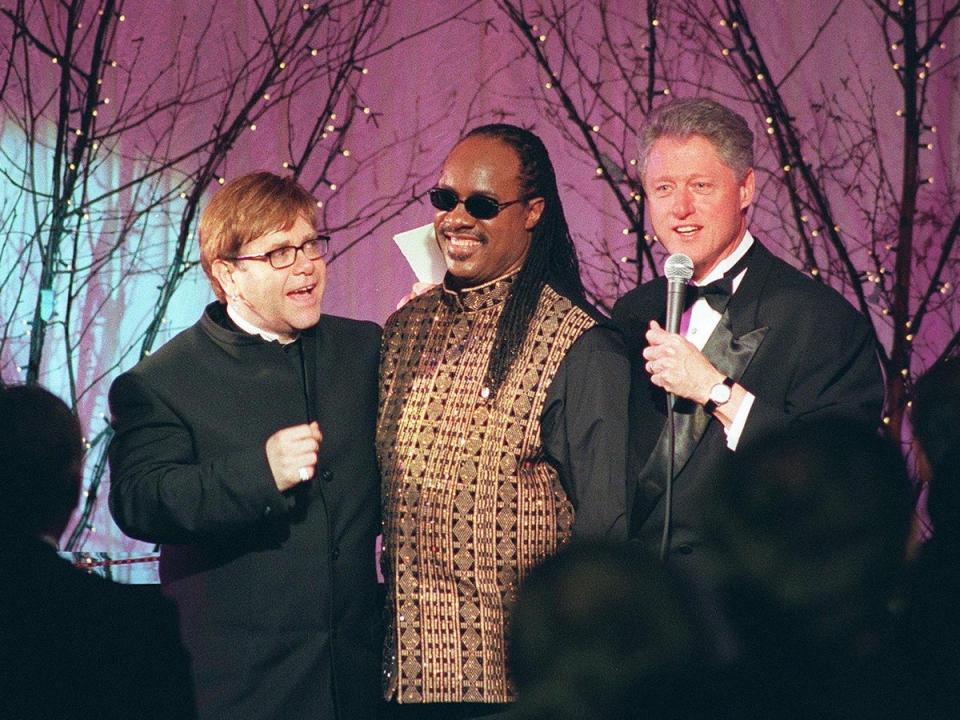

The doctors insisted that Wonder cancel his 20-city Innervisions tour, which had been scheduled to begin at the end of 1973. The hiatus caused him to become extremely nervous about performing live again. His first steps back onto a stage were helped by his friend Elton John, whom he’d known since 1971, when John went to meet Wonder at Heathrow airport and was greeted by the Motown star singing “Your Song”. Two years later, just seven weeks after the crash, Wonder was on board John’s tour jet, flying from New York to Boston for a gig on 25 September 1973. Relaxed and joyful on the flight, Wonder played a medley of John’s hits, including “Crocodile Rock”.

At the Boston Gardens show, John paused his set to say, “A friend of mine is here tonight, he was badly hurt in an accident some time ago...” The 15,000-strong audience went wild, realising Wonder was in attendance. An electric keyboard was brought out and the pair jammed on a version of The Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women” and Wonder’s own “Superstition”. Wonder later described the impromptu performance as the beginning of his public recovery. Still troubled by painful headaches and tiredness, he played one more charity show for a Black college in 1973 and then delayed his next gigs until January 1974, starting with a set in France and a two-shows-an-evening, five-night residency at London’s Rainbow Theatre.

Wonder gradually began to believe that the crash had been destined, because the aftermath took him to “a much better spiritual place that made me aware of a lot of things that concern my life and my future”. Wonder, who was not into drugs, and only drank the occasional beer or glass of Mateus Rosé wine, said after the accident: “I don’t even drink, man.” Forty years after the crash, he still regarded the date as remarkable: “It was on 6 August that I almost died in that car accident. It was also on 6 August – 1988 – that my son Kwame was born. Life is funny.”

Within three years of the crash, Wonder released three albums – Fulfillingness’ First Finale (1974), Songs in the Key of Life (1976), and Journey Through ‘The Secret Life of Plants’ (1979) – which comprise one of the finest bodies of work by any modern musician. His song “Higher Ground”, about redemption and judgement, remains an inspirational masterpiece. And getting into automobiles again doesn’t seem to have posed a problem for the musician. As he told Oprah Winfrey in 2004: “What’s amazing is that I can get in a car, fall asleep, and wake up when I know I’m home.”

Asked once whether the crash had been a defining event in his life, Wonder replied: “It is significant, but I was blessed to come out of it. God gave me life to continue to do things that I would never have done.” Fifty years and 25 Grammys on from that fateful afternoon, we can all be thankful that a musical genius survived a crash on the highway.