Hanya Yanagihara's Paradise found

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sophia Evans/eyevine Hanya Yanagihara in the American Bar at The Savoy, The Strand, London. Yanagihara is an American novelist and travel writer of Hawaiian ancestry. Her first novel, The People in the Trees, based on the real-life case of the virologist Daniel Carleton Gajdusek, was praised as one of the best novels of 2013. © Sophia Evans / eyevine Contact eyevine for more information about using this image: T: +44 (0) 20 8709 8709 E: info@eyevine.com http:///www.eyevine.com

Lispenard Street is precious to Hanya Yanagihara fans. Though it's just two blocks long, the abbreviated thoroughfare along the border of New York City's Tribeca, SoHo, and Chinatown neighborhoods is the site of pilgrimage for dedicated readers of 2015's A Little Life, the author's sleeper-hit second novel. They come to see where protagonist Jude spends the formative, troubled years of his early adulthood. The entire story is so deeply rooted in place, and those places are the sites of such soul-crushing tragedies, that it's impossible to divorce Yanagihara, 47, from her infamous streets. It's one of the first things this reporter tells her when arriving at her apartment — architecturally stunning, meticulously decorated, stuffed with books, of course — which sits in another of her book's symbolic locations in downtown Manhattan. I also relay that yesterday, after finishing A Little Life for the second time and while under the impairment of a sob-induced haze, I took a wrong turn out of the subway and accidentally alighted on Lispenard Street itself.

I'm a bit desperate for her to see a significance there. "That's amazing," she says breathlessly. "It has to mean something." But, she adds, there is no hidden significance behind her geographical decisions. "I don't even like New York," she says with a laugh. She moved here in 1995 and has stayed all these years because it's where her friends live, and she writes her books here because it's what she knows now.

Yanagihara never sought out literary stardom. She has a big day job — editor in chief of T: The New York Times Style Magazine — and A Little Life, which followed her modest-selling debut, The People in the Trees (2013), by all accounts should not have been very popular. It's 720 pages long, and at least 700 of those pages (un-scientifically speaking) are devastatingly sad. It follows four best friends who move to New York after college (two of them to an illegal sublet in a dilapidated Lispenard Street building). As they build careers and go to dinner and meet lovers, the author reveals the devastating backstory for the main character Jude. What was once a social novel crumbles into a grief gospel, with Jude's trauma leaking through every paragraph. But the book was an unlikely success story: After an initial slow burn, it sold more than 2.5 million copies, and was a finalist for the National Book Award and Booker Prize. Yanagihara wasn't sure she would write another novel, but then an idea came to her that felt urgent, and like a story only she could tell. "It was shortly after the Trump inauguration, and during the announcement of the Muslim ban," she says. "I started thinking about the idea of paradise: America as a paradise, and whether we've been interpreting and billing America correctly all this time."

To Paradise’s cover uses a painting by Hubert Vos.

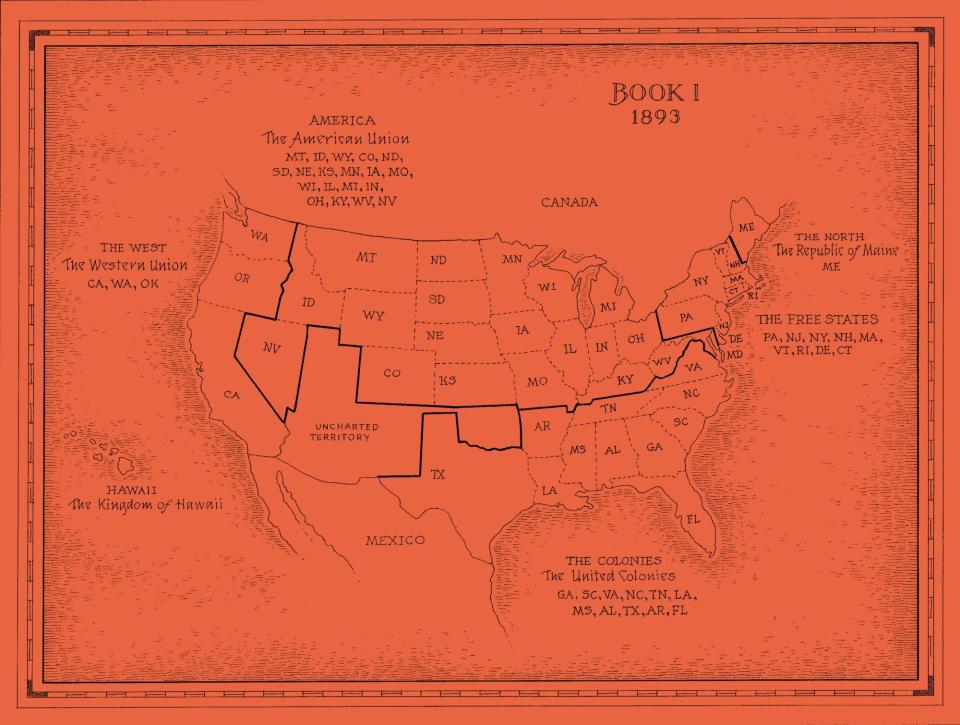

To Paradise is another meaty, emotionally-charged tale — albeit entirely different in plot from its predecessor. It comprises three books, each centered on the same house in Greenwich Village (13 Washington Square North, which is an NYU faculty building), with characters of the same name, but spread across three vastly different and highly fictionalized eras. Book 1 offers an origin story for the novel's version of America: It's 1893 and New York City is part of the Free States, which have seceded from Britain and the Southern states and where gay marriage is not only legal but the norm. Book 2, in 1993, flashes between NYC, where the (unnamed) AIDS epidemic is taking hold, and Hawaii, which has regained independence from the U.S. Book 3 jumps ahead to 2093 — the country is under totalitarian rule, born out of attempts to control multiple pandemic surges and climate change, and Manhattan is divided into strict governing zones. It's a highly realized, deeply imaginative world, but Paradise isn't science fiction so much as another intimate character study.

Each section uses the same names, and many similar identifiers, for its protagonists — David Bingham is the delicate heir to a Free State founding family who questions whether to give up the comfort of life with his grandfather, Charles, to pursue a life with a poor musician, and then a young paralegal living with his older lover (also named Charles, also at 13 Washington Square North), and then the radical activist son of a government scientist. The scientist is Charles, who is eventually arrested, and his granddaughter Charlie is slowly coming to the realization that America is no longer safe. Yanagihara went to work on the novel pondering topics like freedom, self-possession, and the role of traditional family structures — "In A Little Life I did a lot of exploration of friendship; here, I'm exploring what, whether [it's] genetics, law, or something else, comprises a family" — and came out of the writing struck by the ways that climate change and the pandemic have become intertwined with our recent bouts of totalitarian government.

"At what point does an individual stop thinking about society and the way we're all linked?" she posits. "And when we stop, what does it allow a strongman to step in and do?"

EW A map of the reimagined United States in To Paradise

She enters this publication period as a well-known entity; Paradise is easily the most anticipated book of the new year. On the day of this interview, Yanagihara is marked with a famous-author battle wound: While perched on her living-room couch alongside designer throw pillows, she fiddles with a tendonitis brace, the ramifications of completing signatures for the first batch (some 16,000 copies, with more awaiting her pen) of tip-ins, an insert that goes into special-edition books. "And then my mother had me fold 500 wonton, so things really went downhill after that," she says, laughing. It's expected that her latest novel will be as much of a sensation, if not more, than Life.

For this next chapter, the author will repeat some of her well-proven marketing tactics. Back in 2015, she wrangled a friend and magazine colleague — a photo editor she was working with at Condé Nast Traveler —to help with the social media promotion ("It sounds crazy, but Instagram was not really a place where people promoted books at the time," she says), and they've teamed up again on the @toparadisenovel Instagram account. She was also one of the first people to tap into the power of merchandise in the literary space.

Before the current proliferation of status galleys, status totes, and even status bucket hats (thank Sally Rooney's marketing team at Farrar, Straus and Giroux for that one), she used her own money to print a run of tote bags with the characters' names (Jude&JB&Willem&Malcolm) screen-printed across one side. She borrowed the services of T's creative director Patrick Li to elevate Paradise's branded line. She describes the totes as "sort of a Supreme vibe," referencing the cult streetwear brand's signature brightly-hued block logo. "A certain kind of reader — those who consider being a reader to be a key part of their identity — is looking for a more immersive and intimate relationship with a book," she says of her strategy, which was inspired more by her wanting to thank dedicated fans than to boost sales. "If you can provide them with that, it makes things more meaningful. Plus, it's just very fun to come up with different products and projects."

instagram The Status Tote of the 2022 book world.

Yanagihara is clearly savvy, but also claims a bit of detachment from the other by-products of book fame: "I don't read reviews, I don't read any coverage, and I don't really care about specifics on a book's success." Her day job offers a financial buffer — she doesn't rely on her writing career for money, allowing her to focus more on simply making the book she wants to make — and she looks at her marketing strategy as a distraction from the discourse. "Once a book is released, it's not yours anymore, it's the readers'," says the author. "What you can control is how involved you are in the selling of it, and it gives you back a bit of that sense of ownership."

But that doesn't mean she derives no deep pleasure from the simple fact of people all over the world reading — and obsessing over — her work. Even all these years later she appears genuinely humbled and thrilled by what A Little Life has become, and by the prospect of those readers discovering the joys and emotional layers of To Paradise.

Yanagihara embarks on a global tour this month and is looking forward to fielding questions and feedback on the novel's hot-button issues. (It's a good time to note that she'd already conceived of, and was mostly finished writing, the book's pandemic storylines when COVID hit; any similarities between the lockdowns that the 2093 versions of the characters describe and the ones we all went through off the page are coincidence.) And while she revels in the ways fan culture has evolved over the years — her place as a trending topic on TikTok is "remarkable, but also completely confounding." There is one piece of constructive criticism that feels pertinent, however. "My social media manager told me not to say this, but I'm disappointed that no one's stolen the Lispenard Street sign," she says. "Because it seems fairly easy to do. I guess I have a bunch of very law-abiding fans."

Related content: