How a Group of High School Students Helped Crack the 'Redhead Murders' Cold Case Decades Later

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The victims, most of whom were unidentified, were found dumped along major highways in Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Mississippi and West Virginia

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation

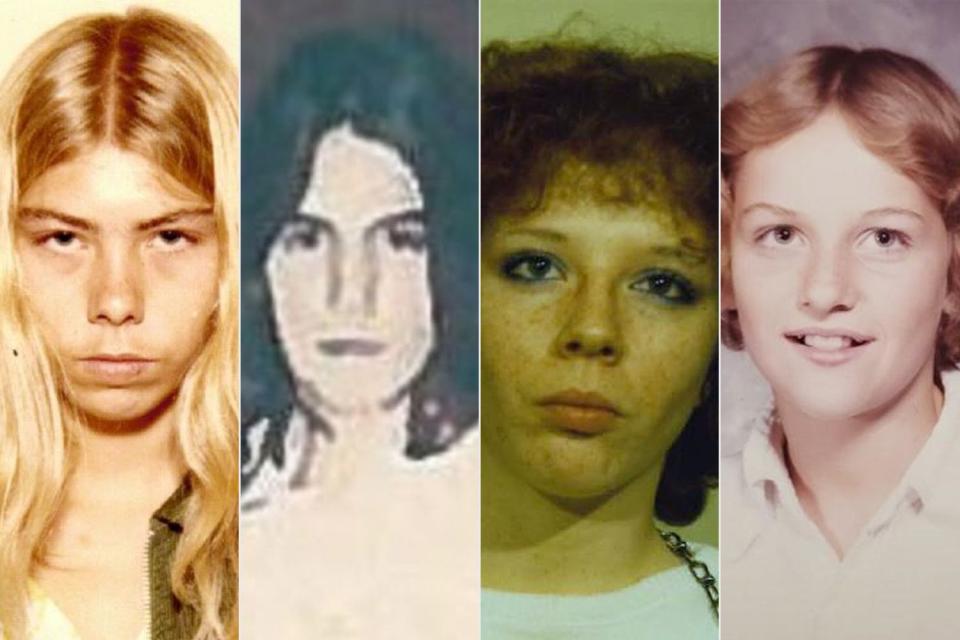

From left, Michelle Inman, Elizabeth Lamotte, Tina McKenney-Farmer, Tracy Sue WalkerA group of Tennessee high school students are bringing to light a series of cold case murders that have stumped law enforcement for more than four decades.

The murders, which were dubbed the "Redhead Murders" because all of the victims had reddish hair, began in the late 70s. The victims, most of whom were unidentified, were found dumped along major highways in Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Mississippi and West Virginia.

It was believed that the killer was probably a trucker and picked up the women at truck stops and disposed of their remains in nearby states but despite investigative efforts in mid '80s, the murders remained unsolved.

The Elizabethton High School students' work on the case, which began in the spring of 2018 as part of a sociology class, is now featured in a 10-episode podcast called Murder 101.

Teacher Alex Campbell says he brought the case to the attention of his students because he likes "projects that get the students interested, projects where we can apply what we're learning in our classes,” he tells PEOPLE. “I had never heard about the murders even though I've lived here my entire life. They had these murders, but nobody had ever come to a consensus whether there was a person responsible for more than one of them, was there a serial killer active?"

The goal for the students, he says, was to uncover whether the killings were the work of one man. They even got the assistance of former FBI agent who helped them learn how to profile a case.

Want to keep up with the latest crime coverage? Sign up for PEOPLE's free True Crime newsletter for breaking crime news, ongoing trial coverage and details of intriguing unsolved cases.

They saw a potential pattern in six of the 12 to 14 murders attributed to the spate of killings and even helped identify one of the victims, Tina McKenney-Farmer, with the help of a podcaster and a true crime buff.

McKenney-Farmer was found dead on January 1, 1985. Her strangled and bound body was discovered along Interstate 75 in Campbell County.

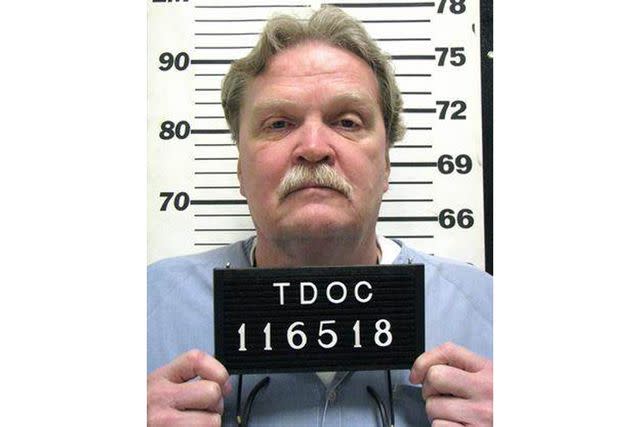

Once she was identified, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation was able to link DNA found at the McKenney-Farmer crime scene to Jerry Johns who died in prison in 2015 after being convicted in 1987 of the attempted murder of a woman he picked up, strangled and then dumped along Interstate 40.

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation

Jerry JohnsAfter pouring through investigative files and talking to former detectives, the students believe there is strong evidence to show that whoever killed McKenney-Farmer most likely killed Lisa Nichols, Michelle Inman, Elizabeth Lamotte, Tracy Walker and an unidentified Jane Doe named DeSoto County Jane Doe.

“There's plenty of evidence for it,” says Campbell.

Campbell says the students are hoping through the podcast they will bring attention to the cases and identify other potential victims.

“They want to spread the word to as many people as possible,” he says. “Get as many people calling in tips and things that they didn't say back then. New witnesses, willing to speak up, political pressure, social pressure on groups to continue the work that needs to be done on these. We've got to hold whoever — if it's Jerry Johns or somebody else — they have to be held responsible for these women. Their families deserve justice.”

About his students' work, Campbell says they "felt like these women didn't have anybody to speak for them, and that's why they were forgotten," he says. "So they wanted to speak for them, and they felt really attached. And some of them started saying, they're almost like family. So they started thinking of them as their six sisters."

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.