The Greatest Biopics Ever Made — IndieWire Critics Survey

Every week, IndieWire asks a select handful of film critics two questions and publishes the results on Monday. (The answer to the second, “What is the best film in theaters right now?”, can be found at the end of this post.)

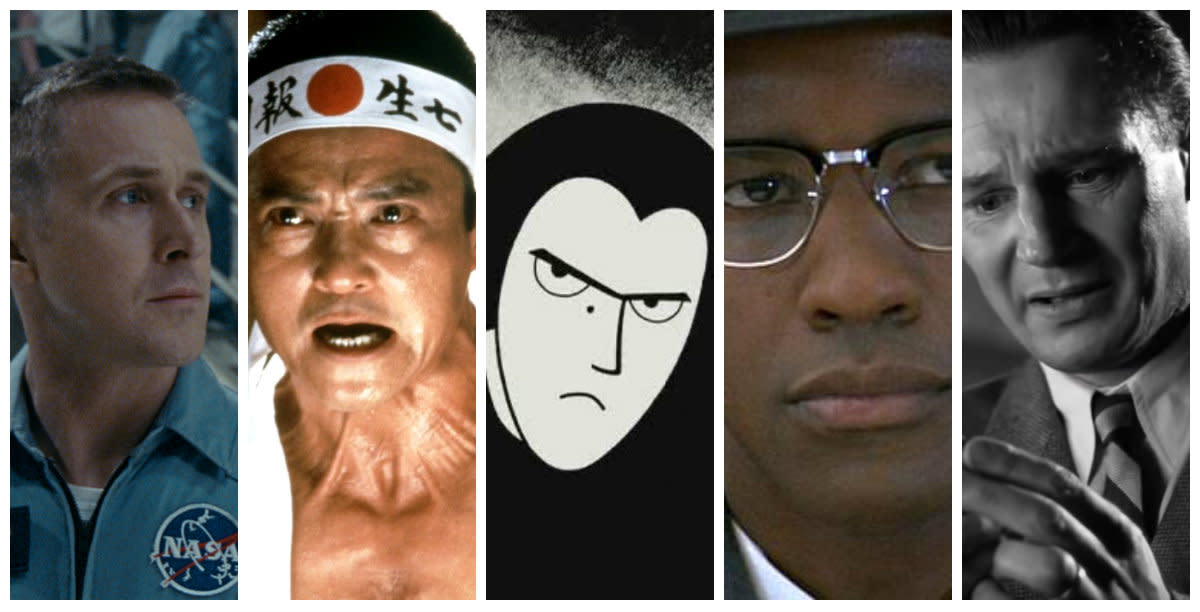

This week’s question: In honor of “First Man,” which is now playing in theaters, what is the greatest biopic of all time?

Matt Zoller Seitz (@mattzollerseitz), RogerEbert.com

The best biographical movie I’ve ever seen was “32 Short Films About Glenn Gould,” because it gets the furthest away from traditional biographical movie structures and has a constant sense of surprise.

Sarah Marrs (@Cinesnark), LaineyGossip.com, Freelance

I’m giving this one to “Amadeus”. It’s not 100% accurate — no biopic is — but where “Amadeus” fudges details it does so in service of its theme. This movie has more to say about competition and rivalry than most sports movies, and it’s one of the only Great Man biopics to observe its subject from the outside. By centering on Salieri, a master in his own right, “Amadeus” shows what it’s like not be a genius, but to be the one cast into the shade of the genius’s burning light. “Amadeus” is a gorgeous film about gorgeous music, and it perfectly captures how much it sucks to be working in the same field as a true genius. Great Man biopics usually show us a world that revolves around the Great Man, but “Amadeus” reminds us how disruptive, and even destructive, Great Men can be to everyone in their orbit.

Alonso Duralde (@aduralde), TheWrap, Linoleum Knife, Who Shot Ya?

So very many choices in this category, but I’ve always loved “American Splendor,” one of the few films that passes the sniff test enough to have its actual subject (comics writer and legendary curmudgeon Harvey Pekar) walk in and out of the movie. (This year’s “American Animals” takes a fairly valiant stab at this in its own way.) Paul Giamatti gives a GOAT performance as Pekar, expressing his working-class blues, his need for creative expression and his lovely romance with fellow comics creator Joyce Brabner (played wonderfully here by Hope Davis). It’s a film that feels lived-in and organic, even with such larger-than-life personalities like Robert Crumb (James Urbaniak) and Toby Radloff (Judah Friedlander) weaving their way in and out of the story. I don’t know why more people aren’t always talking about this modern classic.

Joanna Langfield (@Joannalangfield), The Movie Minute

Perhaps the film biography that made the greatest impression on me, maybe in part because I was such a young, impressionable kid when I first saw it, is “Bonnie and Clyde”. Arthur Penn’s stunning tale of the notorious bandits was evocative, groundbreaking and sexy. Now I recognize the influences of the French Wave directors, the boldness of the romance and violence mix, the unforgettable graphics of the final death scene. Then, I probably just responded to how sexy it was. But then and now, it is still a truly great film.

Christy Lemire, @christylemire, RogerEbert.com, What the Flick?! Podcast

“Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Michael Apted’s film is the gold standard for all biopics but especially music biopics, of which there are so many, they have their own brilliant parody in “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story.” In telling the story of country legend Loretta Lynn, “Coal Miner’s Daughter” created the mold, intimately and thrillingly. All the highs and lows are there that you expect by now in depicting a famous person’s life: the humble beginnings, the rise up the charts, the jealousy and loneliness, the infidelity and — of course — the substance abuse to pump up, wind down and ease the pain. It all sounds like a cliche now, of course. Back then, though, it wasn’t. And much of the reason “Coal Miner’s Daughter” still holds up decades later is because of its powerful, visceral performances from Sissy Spacek and Tommy Lee Jones. Spacek deservedly won the best-actress Oscar for her vibrant portrayal of Lynn over many decades, from childhood through superstardom, and did all her own singing to boot. She also shares lovely chemistry with Beverly D’Angelo as Patsy Cline. Just talking about it makes me want to watch again right now — and I’ve already seen it a million times.

Lindsey Romain (@lindseyromain), Freelance for /Film, Thrillist, and Vulture

I have a real soft spot for “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Sissy Spacek is wonderful in everything but she excels as Loretta Lynn, putting her real singing voice on display and fully inhabiting that high-fluff hair.

Ethan Warren (@ethanrawarren), Bright Wall/Dark Room

I’m not a huge fan of traditional biopics; real lives so rarely conform to anything resembling a satisfying narrative. So from my perspective, the more nontraditional the approach to biography the better, which makes the obvious choice Todd Haynes’ “I’m Not There.” Haynes takes a cubist approach to Bob Dylan’s life and legend, and then (because apparently prismatizing one man into six different characters wasn’t ambitious enough) makes each thread an overt tribute to a specific film or filmmaker, so Dylan’s Greenwich Village years become at times a word-for-word remake of Godard’s “Masculin Féminin,” and the part where Dylan’s spirit is represented by a world-weary Richard Gere in what might be the late 19th century is an overt nod to Sam Peckinpah. It’s decidedly not everyone’s cup of tea, but if you’re an equal fan of Bob Dylan and the Criterion Collection, it’s a one-of-a-kind treat.

Richard Brody (@tnyfrontrow), The New Yorker

The bio-pic is a fascinating genre: because of its inherent relationship to documentable facts, to truth or truthishness or myth, it’s a political genre, one that automatically engages in a dialectical relationship with history. The best bio-pics are ones in which the engagement with politics is self-conscious, in which an idea of history is realized along with the dramatic portraiture. The best directors of bio-pics are the great political filmmakers, and the greatest bio-pic of all is one that realizes character and action on a scale as psychologically colossal and physically vast as the one historical spectrum it depicts and the other that it allegorizes, and with an inventive audacity to match: Eisenstein’s “Ivan the Terrible,” parts I and II.

Oralia Torres (@oraleia), Cinescopia

Although it doesn’t follow a classic biopic structure, “Jackie” is my pick. With Natalie Portman’s mesmerizing performance and a detailed direction, the film presents the perspective of one of the most iconic women in US’s cultural and political history, Jacqueline Kennedy, during her husband’s presidency and right after his sudden death. The film is also about a woman’s lifelong desire and struggle to control her image, deeply tied to her identity, and her family’s legacy. The non-linear approach, the haunting soundtrack, and the carefully detailed production elevates it to one of the best biopics of the century.

Roxana Hadadi (@roxana_hadadi), Pajiba, Chesapeake Family magazine, Punch Drunk Critics

The best biopic of all time is also one of the best films of all time: David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia.”

Lean’s filmography remains, decades after he won two Best Director Oscars within five years for “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and “Lawrence of Arabia,” insane. With those two films, released in 1957 and 1962, respectively, and “Doctor Zhivago,” released in 1965, Lean helmed a series of cinematic classics that will be studied in film classes and adored by movie buffs for years to come. They’re titanic achievements, and even among such greatness, “Lawrence of Arabia” is the zenith, the pinnacle, the almighty. Peter O’Toole has never been better than as the twitchy, peculiar, almost zealous T. E. Lawrence, the man whose involvement in the Arab National Council was alternately sympathetic and patronizing, whose enigmatic personality and mysterious reputation hid a man who felt deeply but tried desperately not to, who didn’t mind burning his fingers or disrupting tenuous political alliances to prove a point.

The movie is heavily fictionalized, yes, but it’s also thoroughly engrossing, with gorgeous cinematography from F. A. Young, a beautiful score from Maurice Jarre, and a performance from Omar Sharif that signified the man was going to be a huge star. No other biopic has left as long a shadow or as powerful an impression of “Lawrence of Arabia,” and even now, thinking about the first few seconds of that dramatic, sweeping score makes me a little teary.

Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@chrisreedfilm), Hammer to Nail, Film Festival Today

I like films that teach us something new about well-known figures, or that turn lesser-known souls into compelling cinematic characters. In the former category, I would pick Bill Pohlad’s 2014 “Love & Mercy,” in which both Paul Dano and John Cusack incarnate Beach Boys frontman Brian Wilson at two different stages of his life. Both actors deliver moving, committed performances, and the scenes of the young Wilson hard at work in the studio show the process of creation in a way few other films get truly right.

Christina Newland (@christinalefou), Freelance for Sight & Sound, Little White Lies, VICE

Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X.”

Mike McGranaghan (@AisleSeat), The Aisle Seat, Screen Rant

No biopic has ever moved me the way Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X” did. At three hours and twenty-two minutes, the film really had the time to take us through Malcolm’s life, exploring how he developed his perspectives and showing how his position evolved over the years. That would not have felt organic with a traditional 120-minute running time. Not many movies can sustain such length, but this one made great use of it. Nothing felt left out, everything felt thoroughly explained. Of course, Denzel Washington’s world-class performance helped immensely. He practically became Malcolm. It was magic.

Andrea Thompson (@areelofonesown), Freelance for The Young Folks, Chicago Reader

The story of how “Malcolm X” finally made it to the screen after decades of false starts is almost as complicated as its subject. But in this case, all the delays feel like pieces of a puzzle that only fell into place when the perfect players arrived to bring the story of the controversial icon to breathtaking life. Any fears that director Spike Lee would try to soften this story vanish from the start, as an American flag burns while we hear Malcolm giving a fiery speech. But rather than heading straight to the civil rights work he’d become known for, Lee takes his time, delving into Malcolm’s early life and his activist parents, his time as a small-time criminal and his subsequent arrest and imprisonment where he converted to Islam and eventually became the man many revere, but so few understand. I knew so little about Malcolm X before I watched Lee’s epic, and the movie made me want to learn more. It triumphs not just due to Denzel Washington’s brilliant, daring performance, but because he and Lee always keep the very complex man, not the icon, front and center.

Gus Edgar-Chan (@edgarreviews), Film Inquiry, Outline Norwich

There are two types of people in this world: those who think “”Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” – a kaleidoscopic character study of author-turned-nationalist Yukio Mishima – is the greatest biopic of all time, and those who haven’t seen it. Schrader’s film gloriously dismisses the genre’s foundations, paints a delirious portrait of its controversial Japanese figure, and directly transmits his flamboyant and flamboyantly contradictory psyche into its viewers via lucid dream.

Read More:‘I, Tonya’ Director Reveals Tonya Harding’s Reaction to the Breakout Biopic — TIFF

Biopics rarely escape the trappings of their forced objectivity. Schrader makes it look easy. Retelling a character’s life is simple enough, but to evoke that figure, along with his ideals and obsessions, is something else entirely. And so we begin not with our protagonist at their deathbed and the promise of a decade-spanning flashback, a structure of the genre defined by “Citizen Kane” and rigidly adhered to since, but with the cryptic image of a black slate of sea and grass, and a red dot threatening to breach the skyline.

By the end of the film, that red dot — a sublime symbol of Japanese tradition — makes its appearance. For Yukio Mishima to reach that point, where “the bright disc of his sun soared up behind his eyelids and exploded”, he has to soar himself: through greens and golds, rotating noodle parlours and a walled set that caves in on itself. Every single facet, from set design to Philip Glass’ stirring score, is pushed to the extreme, the blatant artifice obscuring the conviction of his ideals. There’s nothing quite like “Mishima”, and there may never be again. Schrader has turned the man’s life into a line of poetry written in a splash of blood.

Robert Daniels (@812filmreviews), Freelance

“My Left Foot” immediately springs to mind. Few biopics have had better lead performances than the one by Daniel Day-Lewis. In many respects, it’s peerless.

The trope of alcoholic, troubled, and disabled genius has become almost comical, especially in the sense of John C. Reilly’s “Walk Hard: the Dewey Cox Story.” But Day-Lewis’s performance as Christy Brown doesn’t fall into the clutches of what has made other films inauthentic. It’s a full commitment not only to inhabit the subject’s disability, but to elicit sympathy in a way that doesn’t demean Brown or pander to audiences. He plays the man first, and the disability second, rather than making his performance solely reliant on said disability.

Many films that examine disability start from the stand point of using it as the scope of the person and not a component. The performance and biopic then tends to lack nuance, which nearly happens at the conclusion of “My Left Foot” with an overly optimistic ending, which has in itself become a cliche of the genre. However, in terms of the sum total of the subject, Day-Lewis finds every bit of nuance in every sporadic movement of Brown and emotes emotion with such conviction that we’re convinced he is Christy Brown and will forever be. He elicits inspiration in a film where there should be none, considering the alcoholic and acidic personality of the subject. But much like Brown’s disability, he portrays the alcholism and Brown’s crass tendencies as components of the character, creating a full and complete representation of the man.

“My Left Foot” has been swept up by a genre that’s become all too much of an Oscar click-bait, but much like Brown, it’s so much more than that. It’s Christy Brown’s story.

Ray Pride (@raypride), Newcity

“Once.” Heart on its sleeve, true story embellished, made lavishly musical.

Joel Mayward (@JoelMayward), Cinemayward.com, Freelance

With over 50 movies already made about her life, St Joan of Arc is is second only to Jesus as a religious figure depicted within film. The best of these St Joan biopics is Carl Th. Dreyer’s 1928 “The Passion of Joan of Arc.” Both historically informed–Dreyer used the actual trial proceedings for the script–and revolutionary in its expressionistic transcendental aesthetic, there’s not much more I can add beyond what I wrote for Bright Wall/Dark Room about this cinematic saint. Dreyer’s film is simply a masterpiece.

Carlos Aguilar (@Carlos_Film), The Wrap, MovieMaker Magazine, Remezcla

Appealing to the audiences’ previous knowledge or inherent interest on a subject, biopics are often reserved for emblematic figures. Under these parameters, Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud’s daring animated feature “Persepolis” is an anomaly.

Rather than a biopic in the traditional sense, the film is Satrapi’s auto-biopic based on her own graphic novel by the same name recounting her life growing up in cosmopolitan Iran prior to the revolution in the late 1970s, adjusting to the oppressive mandates of the new Islamic Republic, and eventually relocating to France pursue her artistic interests and escape the hazardous consequences for women with her aspirations in her homeland.

Thanks to the use of hand-drawn, black-and-white animation, what could have been a solemn journey if done in live-action becomes a whirlwind of ideas and observations expressed through visceral, expressionistic, darkly humorous art. Satrapi’s candidness about her young self and her pained yearning for a country she used to know are superbly translated from the original material into the animated medium.

“Persepolis” is a rare first-hand biographical movie where the individual herself comes to terms with her past without a middleman deciphering what the crucial moments of that life were. It’s nothing short of a cinematic self-portrait.

Don Shanahan (@casablancadon), Every Movie Has a Lesson

In this very populated sub-genre field, the best has to be “Raging Bull” for me (and I’m sure I’m not alone). The technical, artistic, and narrative heights of Martin Scorsese’s opus have become the stuff of legend. The stressful and risky tale of Scorsese landing this after a drug overdose and several refusals to save his career with a “swan song” film to leave the filmmaking business is a wild tale in and of itself before the gloriously daring final product would validate careers and the entire art form for its decade and onward.

Viewing Michael Chapman’s stark black-and-white cinematography and his then-revolutionary POV set-up of boxing camerawork through Thelma Schoonmaker’s historically perfect editing, is an absolute marvel to behold with each viewing. After working uncredited with Scorsese to add pulp and muscle to the mash of Paul Schrader’s rewrite of Mardik Martin’s original screenplay, Robert DeNiro’s ferocious Oscar-winning in-ring and out-of-ring performance earned every bit of that second career Academy Award. Physically and emotionally, his transformation into Jake LaMotta is brazenly courageous. His towering lead bolstered two unknowns in Cathy Moriarty and Joe Pesci, who can thank their careers for this film. “Raging Bull” hasn’t weakened a bit with dozens of contemporaries and imitators in nearly 40 years since its debut. For this movie to come out four years after Rocky and a year after its automatic triumphant sequel to stun audiences and critics alike with a completely opposite tonal and visceral experience is something brilliant and miraculous.

Q.V. Hough (@QVHough), Vague Visages

As a collective piece of filmmaking, Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull” triumphs over formulaic biopics.

Depicting the rise and fall of Italian-American boxer Jake La Motta, “Raging Bull” succeeds because of the visual aesthetic, as Scorsese stylizes the boxing sequences and utilizes a stripped-down approach outside of the ring. Just the direction itself makes “Raging Bull’ one of the most polished biopics ever made, and cinephiles can argue all days about whether De Niro’s Method approach outweighs his actual performance. The fact remains that Scorsese and company brilliantly executed their vision.

“Raging Bull” challenges viewers with its domestic violence sequences. Incidentally, many people “don’t relate” to the main character, thus missing the point while dismissing the film as a whole. But Scorsese’s depiction of violence doesn’t glorify male machismo and old school mentalities, just like “The Wolf of Wall Street” doesn’t promote good ol’ behavior and financial excess.

In 2018, “Raging Bull” holds up because of the subtext, the attention to detail and the masked satire; the directorial finesse and the raw performances.

Candice Frederick (@ReelTalker), Freelance for Harper’s Bazaar, The Week, Slash Film

“Ray.” This one immediately springs to mind because it objectively yet compassionately explores the life of a deeply flawed man, a revered musical genius. Though Ray Charles’ life and story is centered and wonderfully portrayed, it still leaves room to highlight amazing performances from the women in his life who had a major influence on him — from his mother Aretha Robinson (Sharon Warren), wife Della Bea Robinson (Kerry Washington), and mistress Margie Hendricks (Regina King). It’s truly astounding.

Anne McCarthy @annemitchmcc Teen Vogue, Ms. Magazine, Bonjour Paris

Hands down, best biopic: “Ray.” That movie, and Jamie Foxx’s performance in it, gave me chills. It was so damn good. You know a movie is good when it stays with you long after you’ve left the theater. Weeks after seeing “Ray,” the performances in it – as well as the songs – were still popping up in my mind. This led me to buy the soundtrack, which led me to become a Ray Charles fan, which led me to have a new favorite song in “Georgia on my Mind.” That’s the power of great film, isn’t it? That ripple effect. It’s how a movie can unexpectedly touch different parts of your life, and change the way you see the world.

Ken Bakely (@kbake_99), Freelance for Film Pulse

Generally speaking, I’ve never considered the biopic to be my favorite genre, but perhaps I’m just averse to the meandering, whole life story format that usually feels so formulaic and contrived, as if it’s telling the story of someone so immediately important that the entire planet stopped and cooperated to foster their success from birth.

Consequently, the best biopics shun this bubble. They hardly feel like biopics at all, because they’re not just zeroed in on a single, isolated person: they seek to understand one human through a broader study of how they exist within the difficult nature of humanity, and vice versa. Using that criteria, it’s hard to top “Schindler’s List,” with its powerful depiction of Oskar Schindler’s redemption and virtue during some of humanity’s darkest days. Despite its focus on his journey from indifferent beneficiary of the Nazi regime to saving over a thousand people from that very same regime, it never feels like it’s under-serving the victims of the Holocaust, nor does it feel as if its dramatic structuring is somehow arbitrary. It’s both deeply specific in its awareness of a responsibility in depicting history, and undeniably cognizant of the universal themes that are observed from its message.

Rob Thomas (@robt77), Madison Capital Times

I have to confess that I’m often bored by conventional biographies. There’s something about the full arc of a human life that more often than not just does not lend itself to a narrative, and every time I read about what a famous person’s childhood was like, my eyes start glazing over. Get to the good part!

So I’m much more partial to biopics that focus on a small but essential part of a person’s life, a part that explains the whole. Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” does this better than any movie I can think of, using the details of the Selma march to give us insight into the fullness of Martin Luther King, Jr. – the stirring speaker, sure, but also the brilliant political tactician, and the human being wrestling with the risks and the cost to his family. He’s all these things, and they all exist on a continuum – the man we knew and the man we never knew. Rather than explain or glorify King, the film simply presents him in all his complexity.

Brianna Zigler (@briannazigs), Screen Queens

“The Social Network” includes the line “You’re gonna go through life thinking that girls don’t like you because you’re a nerd and I want you to know from the bottom of my heart that that won’t be true, it’ll be because you’re an asshole.” So, does this question even need to be asked?

Luke Hicks (@lou_kicks), Film School Rejects, Birth.Movies.Death., Bright Wall/Dark Room

David Fincher’s “The Social Network”. It’s an absolute blast from start to finish, so full of energy it’s practically moving at light speed. You blink, it’s over, and you want to watch it again immediately. It’s the supremely cast story of young tech/social media tycoon Mark Zuckerberg. Jesse Eisenberg (in the biopic’d role), Andrew Garfield, Rooney Mara, Justin Timberlake, Armie Hammer(s), Dakota Johnson, Rashida Jones, Max Minghella, and Brenda Song form an ensemble that could not have been less expected and more apt. Aaron Sorkin’s screenplay is as sharp as they come, providing the groundwork for Fincher’s sensational directorial tricks and perfect pacing.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross blew everyone’s mind with a stunning score none of us could have imagined coming from the Nine Inch Nails duo. Jeff Cronenweth’s cinematography is a godsend. The greatness of this movie runs so deep, even the tagline is unforgettable. And, to top it off, we figured out (sort of) how Facebook happened, which these days is relevant for negative reasons, but relevant all the same! No matter where Facebook ends up in the annals of history (probably on the wrong side, let’s face it), it certainly won’t be forgotten. As of right now, it can’t be. It won’t stop spamming us. We all have Zuckerberg in his ass hole, genius, Harvard-dropout ways to thank for that. And any movie that can make us empathize with someone responsible for such a malignant social atrocity should be eternally lauded.

Dewey Singleton, (@mrsingleton), eatbreathewatch.com, insessionfilm.com, and cc2konline.com

“Straight Outta Compton” is a highly underrated biopic which captures the essence of a culture which revolutionized music. The movie should garnered more attention during awards season due to any number of fantastic performances.

Danielle Solzman (@DanielleSATM), Solzy at the Movies / Freelance

I’m partial to “Walk the Line.” It wasn’t only that Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon were amazing in this film, but also that they put in the effort to learn these songs. I’m personally a fan of the films in which the actors are singing live-to-tape rather than lip syncing the songs. There’s something about Cash’s music that made for a soundtrack that one can listen to on repeat. The renditions in the film are their own, but they don’t step on the Cashs’ legacy. And without this film, we don’t get the pure joy that is “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story.”

The Best Movie Currently in Theaters: “First Man”

Related stories

'First Man' Struggles to Place Third; 'Venom' Still No. 1, but 'A Star Is Born' Stays Strong