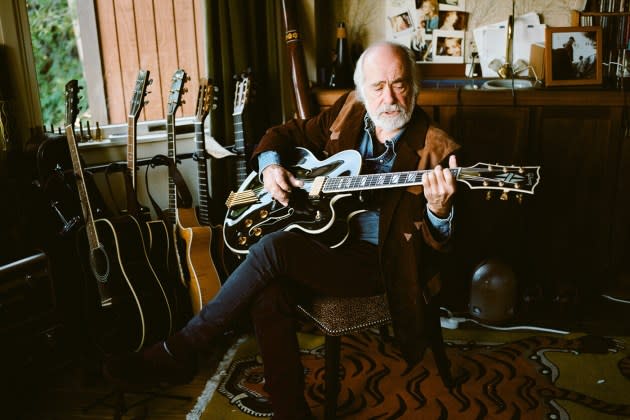

Grateful Dead’s Robert Hunter on Jerry’s Final Days: ‘We Were Brothers’

In part one of Rolling Stone‘s exclusive interview with Robert Hunter, the legendary (and fairly reclusive) Grateful Dead lyricist looked back on his early years with the band: meeting Jerry Garcia, signing on as the primary in-house poet and writing epic Dead songs from “Dark Star” through “Truckin’.” In this second and last part, Hunter, speaking at his home in Marin County, talks candidly about the rougher waters that followed. As becomes clear in the conversation, few in the Dead world were as affected by Garcia’s addiction issues as Hunter. Yet despite the troubles, the two still managed to write songs that have endured, from “Touch of Grey” and “Standing on the Moon” to “So Many Roads” and “Days Between.”

You had a legendary songwriting binge in London in 1970.

[Nods] “Ripple,” “Brokedown Palace” and “To Lay Me Down.” Everybody went away and left me alone for the afternoon with a bottle of Retsina and a beautiful London day. I’d never been in London before so it was all new to me. They had this beautiful parchment paper in the room — a stick of it that just called out for things be written on it. And that stuff just poured out…. One thing Jerry wouldn’t do is go back over and redo parts of songs. I’d written that extra verse for “Friend of the Devil” and he said, “Why the hell don’t you give me these things before I record them?” And also the same with “Rubin and Cherise.” I had some ending Orpheus and Eurydice stuff in there to complete the story. He liked it but said, “I’ve already recorded it and can’t go back and do it again.”

More from Rolling Stone

Robert Hunter on Grateful Dead's Early Days, Wild Tours, 'Sacred' Songs

Lost Robert Hunter Manuscript Chronicling Birth of the Grateful Dead to Be Released

Did you write lyrics in Jerry’s voice sometimes, things he couldn’t express or articulate?

That was never requested of me. But more from many nights of raving all night the way people do in their early twenties, he knew me real well and I knew him real well, and I remember his girlfriend at that time, she said it was hard to tell where he ended and I started up. We were brothers in that sense. I loved that band until I didn’t give a damn about ’em, I’ll say that. I really just thought they were the cat’s whiskers.

When did you stop thinking that?

I made that statement, and I should be able to justify it. It’s when cocaine took over the band, everybody talking through their hat, all the time, continuously. I had gotten done with my speed trips before I joined the band. I had no interest in coking or anything else — I had been there and hurt myself. And it just kept coming in and in — cocaine! What I did at that point [the mid-Seventies] was move to England. I spent a lot of time going back and forth and a lot of time living there. Not that I was tired of the band or the guys in the band. The whole surrounding scene was… heavy. So I did what I should’ve done, I got out. And then we moved back [to the States] because the money had run out.

People have often interpreted “Ship of Fools” as your comment on the Dead scene around that time, 1974.

I debate myself about that one. I could certainly make a case for it, and I could also say that it was a bit more universal. I’m open to questions about interpretation, but I generally skate around my answers because I don’t want to put those songs in a box. “New Speedway Boogie” is about Altamont, you know: “Please don’t dominate the rap, Jack.” Jack was [writer] Ralph J. Gleason, and why are you laying all this blame on us? It was badly conceived to move that thing from Golden Gate Park. We were going to do the show for free there, and then suddenly after the Rolling Stones were involved, San Francisco said no, so we went to Altamont. Had to do it. Now is it our fault or is it the San Francisco city council’s fault that that went down? Who’s to say, you know, so in time we may understand. That’s what the song says, and in time we may not understand.

You didn’t go to Altamont, right?

No, I didn’t, I went to see Easy Rider that day one way or another. I don’t like festivals, or I didn’t at the time. I didn’t go to Woodstock or Watkins Glen.

Was “Althea” written about Jerry?

No.

Some think some of those lines — “ain’t nobody messing with you but you/but your friends are getting most concerned” — were for Jerry, especially when hard drugs entered the scene.

Hmm… you think? You know, people think I have a lot more intention at what I do because it sounds very focused and intentional. Sometimes I just write the next line that occurs to me, and then I stand back and look at it and say, “This looks like it works.” But that does kind of sound like a message to him. There were other people messing with him.

In 1982, the Dead started playing “Keep Your Day Job,” a new song you’d written with Garcia, but it was dropped from the set soon after. Some fans thought it was a criticism of following the band around on the road.

I don’t think they were really listening to it. They didn’t like the idea. I was saying, “Keep your day job, support yourself, whether you like that gig or not.” You had to do your job while you’re lining up your long shot. That just makes good sense. It was a nice uptempo song with a catchy lyric. A couple of people reacted, and it became a thing to dislike “Keep Your Day Job.” They didn’t like the meaning, or what they perceived as the meaning.

When Jerry was busted in 1985, was it all catching up with him?

We all went over once to his house and confronted him, and he opened the door and saw what was going on and said, “Get out of here!” He was trying to shut the door and we all filed in and did the confrontation you could do. And he said he’d do something about it. That’s about all you can do, isn’t it? All I can say is that it more or less ruined everything, having Jerry be a junkie. I remember a time when “junkie” was the nastiest thing Garcia could call anybody. You had such contempt for anybody that would get involved in that.

But what are you going to do when you’re elevated the way he was? He once said, “They’re trying to crucify me, man.” And I said, “Jerry, never mistake yourself for Jesus Christ.” And he really took that advice. He took it hard and well. You’ve got to understand the whole weight of the Grateful Dead scene was on Jerry’s shoulders, to support all the families and everything as well as the audience’s expectations. There were times when I just drove him through the wall.

The time Jerry got busted in Golden Gate Park, they took his briefcase. I haven’t gone searching for it, but I happen to know that briefcase had a number of new songs he was working on. And if the police still have them, I’d like them back, please. It doesn’t seem right. A lot of those songs disappeared. I would give [Bob] Weir the only copy of a song, and he’d put it in his back pocket and he would do the wash and there would go that song. And he’d say, “Do you remember any of that song?” and I’d say, “Maybe I can remember a verse or two.” But that’s one good thing about word processors coming along — there are no more lost songs.

Then Jerry had his coma in 1986.

Jerry was diabetic, and before he had a coma, he was guzzling down fruit juice. It would’ve been better if he was guzzling down brandy. I believe that sugar put Jerry where he was. He was in terrible health — diabetic and taking immense amounts of sugar, and it did what sugar will do to a diabetic and overloaded him into a coma. I remember going in to see him when he was coming out of it, and he was saying, “Am I insane?” And I said, “No, man, you’ve been very, very ill, but you’re fine, you know, you’re coming out of it.” And he said, “I’ve seen the most amazing thing.” He’d been somewhere.

The following year, the band has its biggest hit ever with “Touch of Grey.”

“Touch of Grey” was not your everyday song. Still is startling to hear it in the supermarket. A lot of people put it down, as if it’s not right for us to be popular and all that! I was living with [my wife] Maureen in a 15th-century house on the west coast of England, and one morning I wrote that thing. Jerry and [bassist and Garcia Band member] John Kahn and I were making an album of mine that never got finished, and Jerry said, “Would you mind if I reset the music to ‘Touch of Grey’ and use it for the band?” And I said, “No, go ahead.” The line “light a candle, curse the glare” is Jerry’s addition to it. My version wasn’t that bad, but [on the Dead’s version] it was that rhythm and rather excellent chord changes, moving from E to C sharp minor and interesting things.

What inspired that song?

You know, I’ll give you the blistering truth about it. A friend brought over a hunk of very good cocaine. I stayed up all night. And at dawn I wrote that song. That was the last time I ever used cocaine. Nor had I used it for many years before that. Now I listen to it and it’s that attitude you get when you’ve been up all night speeding and you’re absolutely the dregs. I think I got it down in that song.

You went scuba diving with Jerry in Hawaii during this period. How important was that to him?

That was his natural habitat. He was at one with that, underwater. You ever scuba dive? There’s nothing like it. One of my nicest memories was coming back onto the boat with Jerry while we were diving and there was beautiful Hawaiian sunshine and dozens and dozens of dolphins were following us along. They were with us, not just following us. That whole underwater environment was good for him. Better than smack.

One of your and Garcia’s last collaborations, “Days Between,” in 1993, felt like a genuine breakthrough into a new type of song.

I’ve heard Jerry do versions of that and leave you a puddle. That is the story of what went down as far as I can see. More so than any other single song. It seemed to get my feeling about those times and our place in it. Jerry didn’t die that much… you know, a couple years after that. He had been into rehab again, and he called me up and he was out and he was going to come over and we were going to get writing again and he said some wonderful stuff that was very uncharacteristic of him. He said, “Your words never stuck in my throat.” Jerry didn’t tend to talk like that, and there was something possibly, slightly alarming about it because he was dead within a week or so after that.

Alarming in what way?

Jerry wasn’t like that — to hand out appreciation that way. It was always implicit with him. Perhaps there was a finality to it, that that was the last statement, whether or not he knew he was going to die in a week or not. Apparently he died with a smile on his face, though. Uhh! Those were the heavy times.

Was that your last conversation with him?

Yeah. He said he had to go to a party he couldn’t get out of, so he said he’d come over in a couple of days like that. But he didn’t. Both of us were hot to get down on the method we used for “Days Between.” That went way, way outside in the way of construction. Up in the pool house here is where Jerry and I wrote “Days Between.” I have a little electric piano up there and I gave him the strange first verse I’d written with very irregular lines and he was sitting there and he worked a melody out. While he was working the melody out I was the writing the second verse and I got it to him, and then he’d start working the second verse out, and then I’d do it while I was doing third verse. I’m so proud of that song. Both of us were very interested in where we could go with that kind of strange and irregular construction. I almost feel in certain respects we were just getting started. We were past one whole phase of writing, and “Days Between” signaled the next.

Did you know he was going to the rehab facility where he died?

No, I knew nothing about that. I have no idea about what went down there. That was headline news — Bill Clinton, the president, even said something. I mean, gosh, how popular was this guy? He was popular for depth rather than flash or timeliness. And my feeling is Jerry will be remembered along with a very, very select few of our age group.

Did you see his death coming?

I always saw it coming, but seeing it coming is not the same as seeing it. I didn’t get the feeling he intended to live for very long. In fact he had said as much, at one point I can remember. He was conscious that it was not going to last forever, nor did I think he wanted it to. There are things about Jerry I just don’t understand. Or maybe am not capable of knowing.

His psychology, in other words?

Yeah. There was an aspect of him that was rather deeply depressive, which people don’t know about. You think Jolly Jerry, and that’s fine when he’s singing. But that man had an agony almost that he had to fight. I suppose it had something to do with losing his dad so young, and possibly his finger getting chopped off. Who knows, but there was a decided darkness to him. But you know, what great man doesn’t have that? His bright side, his ebullient side, far seemed to outweigh [it]. The darkness came into his music a lot. And without it, what would that music have been? Hearing him sing “Days Between,” you know — an agonizing cry from the heart, the way he would sing that sometimes.

At Garcia’s memorial service in 1995, people still remember that powerful poem you wrote and read for the occasion.

I walked up to the front there and his coffin was over to the right and I was reading this stuff and I looked over at that direction. I couldn’t really see him, but I could see the black T-shirt or whatever it was. All of a sudden I got the shakes so bad. I was just reading with my hands like that. Afterwards I didn’t go up and look at him. I just couldn’t. I could not picture Garcia dead and I haven’t seen him dead.

Do you think you’ve come to terms with his death?

[Sighs] I can’t answer that. I don’t know. There are times when suddenly I realize there’s some residual grief and always will be. There was none like him. Irreplaceable. It always felt like it would never end. And then all of a sudden it was gone. It was gone with Garcia.

What are your favorite covers of songs you wrote with him?

I liked Elvis’ “Ship of Fools” a lot. And who’s that band that did “Ripple”? Jane’s Addiction. That was incredible! I almost dropped my chewing gum.

Do you keep up with new music?

My daughter made sure I listen to… what’s that guy from Nine Inch Nails? Trent Reznor. She makes sure I’m aware of everything Trent is doing. I’m not an authority on him by any means, but I appreciate what he’s doing. I watched that thing they did in Golden Gate Park on TV, and I was very impressed, somebody putting that kind of power into it.

Last fall, the Dead signed a new publishing deal with Universal Music, which, as before, gives you veto power over use of songs (with your lyrics) in commercials and soundtracks.

I don’t approve things that are in obvious bad taste. I don’t approve things that want to use the Grateful Dead specifically because of their drug-related connections. I insist the Grateful Dead stuff be treated with respect or you can take your contract and go away. If you want to treat it as some kind of joke, hell with you. I figure it’ll be 50 years from now or longer before all the ridicule the Grateful Dead have received for being hippies and druggies melts away and they can look at the material for what it is. I still feel there is something real in it because I put my effort into it, and if I allow it to be sabotaged, I’m not only sabotaging my work but the work that a great number of people have accepted into their lives and identify with. Levi’s offered half a million dollars to use “Truckin'” or something–which was a lot of money back in the early Seventies — and I said no.

My other big decision was on the back of American Beauty. They had a photograph of everybody with guns, and I said “No!” I don’t say no very often, and I don’t know who I am to say no, but I said no in a big fashion and they left it off. Can you imagine the back of American Beauty with the Grateful Dead armed to the teeth? There are some things that are just a matter of taste. I can’t say I was right or wrong, but man, you can tell now I was right about that.

Does it ever surprise you how long this music has endured?

OK, to get very egotistical about it, way back when I thought we were making music for the ages. I thought that’s what we were doing and it’s what I tried to do. It’s what Jerry was trying to do. That’s one of the reasons we based our stuff very heavily on traditional music as a continuity with that tradition. That it worked out that way and continued to survive was not a big surprise…. I look back and I’ve realized what marvelous good luck I’ve had and a lot of it has it do with the persistent loyalty of fans. That’s a blessing! I won’t play for a couple of years and I forget. Playing Grateful Dead songs to Grateful Dead fans — there’s nothing to compare to that, being up onstage and doing “Ripple” in front of people who’ve grown up with that song. They love it, and I’m able to give it to them as close to the source as you’re going to get.

Best of Rolling Stone