Grammy-Nominated Songwriters on ‘The Most Important Part of a Song’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When the Recording Academy announced the new songwriter of the year category in 2022, the move was widely praised — and considered a rare win for the songwriting community, which has faced major economic challenges in the streaming and TikTok era.

“With the visibility brought by this award comes power,” says Justin Tranter, one of the five nominees for the honor this year. “The more that people know we exist, the more we can make sure the next generation is taken care of.”

More from Billboard

Along with the new category, the academy created a new Songwriters & Composers Wing, helmed by hit-maker and Seeker Music CEO Evan Bogart, to continue expanding its outreach to the songwriter community. “The underpinning of what we do as an academy is built on songs,” Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason Jr., said when announcing the new award and wing. “I started out as a songwriter myself, so the idea of honoring someone who is truly a professional songwriter and craftsperson is special.”

Though producers and artists often play a role in the songwriting process, the songwriter of the year award has specific rules to ensure that it honors the career songwriters who spend their days working primarily on melodies and lyrics, making it the rare space that formally honors the craft.

“As a songwriter, your job is to serve the artist,” the honor’s inaugural winner, Tobias Jesso Jr., told Grammy.com after his victory. “To have this symbol of ‘Hey, you can be creative as a songwriter and just be a songwriter who doesn’t sing and doesn’t produce, and you can get this prestigious symbol of your gifts that the world will now recognize’ — I think that’s a wonderful thing.”

When Billboard convenes this year’s nominees — a remarkably diverse sampling of today’s foremost hit-makers comprising Tranter, Jessie Jo Dillon, Shane McAnally, Edgar Barrera and Theron Thomas — the five songwriters express similar sentiments to Jesso’s and have an immediate camaraderie in conversation stemming from their shared vocation. “Songwriting is the most important part of a song,” Barrera says, “and it always will be.”

Every Billboard Hot 100 hit starts with the work of songwriters and producers. Though there has been a producer of the year, non-classical award at the Grammys since 1975, songwriters didn’t have their own category until last year. Why is it important that there’s a separate category to specifically honor songwriters?

Edgar Barrera: I do a lot of production, but I start my songs on guitar, and I produce after I have the song. Having a songwriter of the year award is super important because songwriting is the most important thing. Without a song there’s no touring, there’s no production, there’s no artists. There’s nothing.

Theron Thomas: I’ve never seen anybody sing along to a beat. I’m sorry. They don’t. They sing the words. Those lyrics touch people.

Justin Tranter: People say [of] awards that “Oh, it’s just an honor to be nominated.” Sometimes I think that’s bullsh-t, but with these four other nominees, I mean it. These are some of my favorite songwriters, period. To be in this company? Holy f–k!

Have you all followed your fellow nominees’ work over the years? If so, is there anything you particularly admire?

Barrera: I’ve actually worked with Theron a lot. He’s the only one I’ve worked with from here. I wish I could work with everyone soon. I’ve been a fan of everyone here. Justin has been a huge inspiration to me, just hearing him talk about songwriters’ rights and everything. Hats off to you, Justin. You’re standing up for all of us. I wish we could all hang out. We all need to get together during Grammy week.

Thomas: Oh, we 100% have to. We got to write a song together.

Shane McAnally: That would be so amazing.

Barrera: That would be pretty interesting, having all the Grammy nominees write together. All different genres.

What moment made you feel like you had made it as a songwriter? Was this songwriter of the year nomination one of those career-defining moments?

McAnally: I don’t think I’ve had that “made it” moment. (Laughs.) I’m kidding. When I was 33, almost 20 years in at that point, I lost my house, lost my car. I was really done. Finally, I had a song recorded by Lee Ann Womack [2008’s “Last Call”], and it gave me this moment of like, “OK, I have a thread to hang on to.” But for me, I really exhaled for the first time when I won a Grammy with Kacey Musgraves [best country album and best country song for 2013’s Same Trailer Different Park and its single “Merry Go ’Round,” respectively]. I remember thinking, “How did this happen? It has fallen apart so many times.” I rode on that wave for a while, but this nomination? I mean, this is really special. This is a moment for me.

I feel so outside of things. Country music is dominating right now, but it’s the artists I don’t work with — Morgan Wallen, Luke Combs and Zach Bryan — so for this nomination to come now is a big deal. There’s a gap in political views for me, with Morgan specifically, and they’re just from a different group. I don’t want to stereotype or lump everyone together, but sometimes you just feel outside while other people are killing it, and to be acknowledged this year, when [my work] wasn’t maybe as commercially obvious as some of my past years, feels amazing. I also feel really good about the integrity of this group of [nominees]. I think I’m really good at this, and I’ve worked my ass off, but it feels really nice to be acknowledged right now.

Tranter: I’m beautifully delusional, and at 15, I was like, “I am the best,” even though that didn’t mean my songs were good; at 15, they were actually quite unlistenable. (Laughs.) But I’ve always been delusionally positive.

There was a moment when my band [Semi Precious Weapons] was ending, and I was considering going back to work in retail. I was with Tricky Stewart, the legendary producer, and he was like, “You’re a really good songwriter. I don’t think you should give up on music just yet.” I was 33, and if you’re in the music business at 33 without any success, it’s starting to look like maybe it is time to pack it up. Having someone like Tricky say that to me was a turning point. I’ll never forget when my first hit, “Centuries” by Fall Out Boy, went No. 2 on iTunes in 2014. I was like, “That’s it. I’ve made it. If this is my life and this is all the success there was, then I am OK with that.”

This year, it has been really special because I intentionally worked on newer artists and wanted to push myself and work on projects where I could really shine lyrically, which is my favorite part of songs. To see that the bulk of my submissions for songwriter of the year are very new artists that the general population is not aware of yet is special.

Jessie Jo Dillon: My dad [Dean Dillon] is a songwriter. He’s in the Country Music Hall of Fame, so I always had a huge complex about him. I was massively insecure. In my first publishing deal, I wrote with Mark Nesler, who wrote many songs I grew up loving. We were leaving the write and he said, “Hey, I just want to tell you something. You’re supposed to be doing this. You just have to trust yourself and keep doing it.” I’ll never forget him saying that. Shane is also one of the first people that told me I was any good, too, and I loved so much of his writing. It has all been other writers that made me feel like I was going to make it.

Jessie Jo, your father came up in a very different time in the music business than you. Have you ever talked about the differences in being a songwriter from his generation to yours?

Dillon: I honestly don’t know how to give advice to newer songwriters. It used to be that you’d show up to a publisher and say, “Hey, I’ve been writing these songs. What do you think?” It feels like such a different game to break into now. I worry all the time that true, blue-collar songwriters who are writing every day in Nashville are going away. My dad says the money was much better in, say, the ’90s. Now because of streaming and everything, it’s hard to make ends meet. Maybe I’m being dramatic…

Tranter: No, I think you’re completely right. For me, fighting for songwriters’ rights is so easy because it’s not about me. I’ve had songs that have hit the top five at pop radio, which means my life is fantastic. Because I’m the lucky one, I need to fight for the next generation of songwriters.

I know a few young songwriters who are so talented. Their catalogs have a couple billion streams cumulatively, but one of them is still driving Uber. One is doing OnlyFans. They are doing whatever it takes to survive. If a song doesn’t go to radio, you don’t have much of anything. I think it’s very fair to say that the middle class of songwriters is going to be decimated — and it already is.

Barrera: It is looking really bad. In Latin, there are managers who get songwriting credits [despite not contributing to the songwriting] like it’s normal. It’s disrespectful to us because we write songs as our only source of income, but managers have a lot of other sources. I know a lot of big writers are still struggling. I feel bad for the next generation. I’m 33 years old, and I’ve been looking at all of this transition. Getting a radio single is really one of the only ways to make real money.

Dillon: It makes me sad to think about the next Diane Warren or Bernie Taupin, moving to Los Angeles or Nashville or Miami or New York or wherever, and that they maybe wouldn’t even get a publishing deal or be able to sustain themselves. Sometimes it takes a writer years of development to reach their full potential.

Barrera: There should be a songwriter fee, like there is for a producer. It’s not fair that the producer is the only one to make money from day one.

Thomas: Us talking like we are right now and standing up for each other is so important. I do have some producer friends who stand up for me, too, which I appreciate. They are like, “Yo, make sure you take care of Theron.” Communicating with each other, sticking up for the next generation and setting the standard high for ourselves can make things better. I think [fear of missing out] on a big record is the reason why a lot of executives get away with giving songwriters almost nothing. A lot of us fear missing out on being in the writing room on a big song because we speak up.

Edgar, what moment made you feel like you had made it as a songwriter?

Barrera: Getting nominated for this Grammy. For me, that’s huge coming from the Latin market. Just getting to make it with Spanish songs. I was like, “What’s going on?” That’s when I realized that music almost has no language, no barriers. We’re a minority part of the music business, and we are changing the game for the Latin community. That’s why it was such an important moment.

Regional Mexican music had an especially big year in 2023, and you played a role in propelling its success. What is it like to be nominated during this pivotal year for the genre in particular, Edgar?

Barrera: I’ve worked with a lot of big names in Latin music, and this year was different because I decided to go back to my hometown [of McAllen, Texas] and support a local act, Grupo Frontera. We grew up together. Where we are from, on the border of Mexico and the U.S., being a songwriter and producer is not even a thing to be in life, you know? Getting the opportunity to support local acts and having them on a song with Bad Bunny, it just doesn’t happen every day. They’re so humble and for me, that’s what I enjoyed the most.

Before this, [Grupo Frontera’s] singer was making fences in McAllen, Texas. The accordion player was selling cows. The percussion player was selling cars. I met all those guys when they performed at a local tire shop for 20 people. Nobody was paying attention to them. They said, “We love what you write. Can you help us out?” And I said, “Of course, why not?” It has been life-changing. This is what is truly important — being part of a movement for regional Mexican with people I grew up with. It’s so full circle.

Theron, what moment made you feel like you had made it as a songwriter?

Thomas: I moved here with $35 from St. Thomas [in the U.S. Virgin Islands]. I went to Miami, slept on the floor, moved to Atlanta. I [have] never felt like I made it because I always feel like I’m one hit away from having to tell my wife and kids, “It’s over. We’re going back to our first apartment with three kids and two bedrooms.” I am doing really well and money is no issue, but you know what I mean? I don’t want to lie and make something up. I don’t know if I’ve necessarily had [that moment]. I’m just minding my business and continuously working every day.

A couple of you mentioned what an honor it is to be nominated based on true passion projects. How do you balance taking on sessions with big names with great chances at commercial success — but that may not be as creatively fulfilling — and sessions with smaller artists that bring you creativity and joy but likely won’t result in a commercial hit?

McAnally: I’ve done the years of trying to get in every commercial room, and now I really like going with something I’m passionate about. Nobody has any idea what’s going to happen with songs nowadays. New artists can go viral in seconds. Old songs can, too. You just never know.

I have always had the most fun and the most success with things that I saw through from the beginning. I was there right when Kacey Musgraves came to Nashville. I was there when Sam Hunt came to Nashville. I was so enamored with what we were making because it was new, and we didn’t know if they were ever going to have success. I’m trying to get back to that.

Tranter: I was just looking at the Instagram account @indiesleaze, which is all photos from the era my band came up in. It was punk as f–k and gay as f–k. And I thought to myself, “25-year-old me would be so embarrassed [by] half of my catalog,” but hey, I got to make music the whole world has heard and my parents got to retire. I could not be more grateful for the songs that 25-year-old me would be talking sh-t about.

I am in a place now where I want to get back to “Do I f–king love this song?” And listen, I have my hits that I am so proud of, but now I want every single song that comes out from here on out to be something 43-year-old me is proud of and 25-year-old me is proud of, too.

Barrera: I’ve always been involved with artists that are up and coming. Working with big names is enjoyable, too, but for me, giving another song to a big-name artist is not that life-changing. I try to be involved from the beginning. For example, I met Maluma way before he was famous. We started off together. I helped him mold his music. I’ve done that with Christian Nodal and Camilo. I’ve always been involved from the very beginning because I feel like I can experiment a lot more with up-and-coming artists.

You’re an extremely diverse group, hailing from different genres, nationalities, races, genders and sexual orientations. Why is writers’ room diversity important?

Tranter: I just think it’s the right thing to do for humanity, but the way to really understand how important diversity in the writers’ room is [is] to show that it’s great for business. We are trying to make music that the whole world loves. The more diverse your writing room is, the more diverse the audience is going to be that enjoys that music.

I have a rule that I don’t write songs for women without a woman writer in the room. This is not because I’m trying to be a great person; it’s because I know it’s going to be a better song when a woman is writing, capturing her real lived experiences in the world.

How will you be celebrating on Grammy night?

Barrera: I’m going, and I want to see all these guys there. It is not a matter of winning or not. That night, for me, is to meet Shane, Justin, Jessie Jo and hang out with Theron. I’m just here for fun. I think we all deserve a night of fun… or a week, maybe. (Laughs.)

McAnally: I’ll be there this year to celebrate. I bought a suit for the Tonys that wasn’t ready in time, and now I have the perfect place to wear it.

Tranter: I am going for sure. We worked so hard to get nominated. I will be there with my mom and dad. I will look unbelievable. I’m going to have a f–king blast.

Thomas: I’m definitely going. Last year, I won record of the year with Lizzo for “About Damn Time,” [but] they [had] put me in the nosebleeds. I couldn’t go up onstage. When we won, I just cried. Not because I couldn’t go up there, but because I wanted to win so badly. I was so happy, but this year? We’re going to have better seats in that thing! Don’t tell on me, but I might need to sneak a little drink in there, too.

McAnally: I mean, I hope they get us better seats.

Thomas: Honestly, I’m just looking forward to meeting everyone. Last year was the first year they had this award, and I remember saying to myself that I wanted to be in the songwriter of the year category someday. Here I am this year — I’m in it, and I’m in it with you guys. Words can’t really express how this moment feels as a songwriter. To be celebrated on one of the most important nights in music, chosen by our peers. I’m excited about that, period.

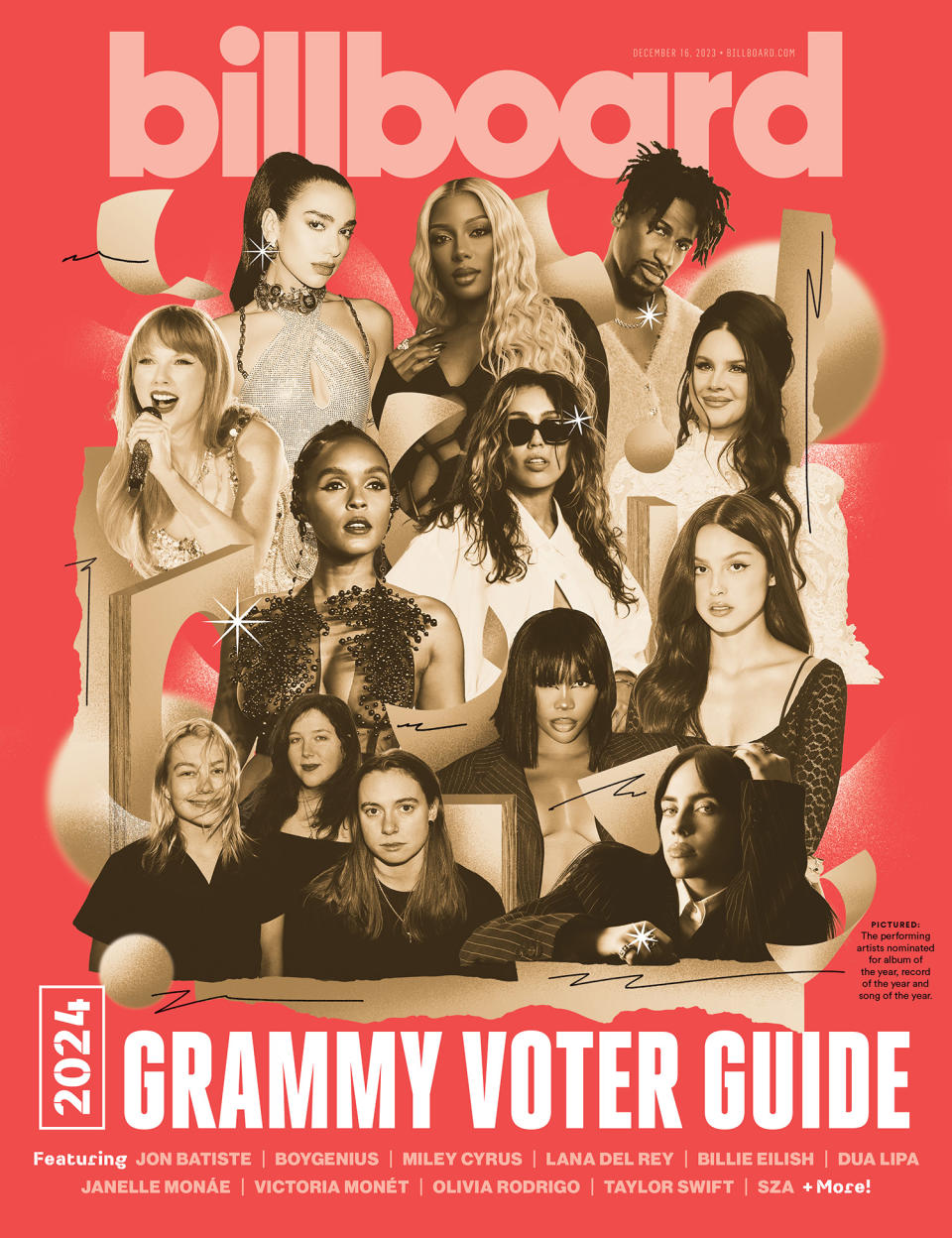

This story will appear in the Dec. 16, 2023, issue of Billboard.

Best of Billboard

H.E.R. & Chris Brown 'Come Through' to No. 1 on Adult R&B Airplay Chart

Anne Wilson's 'I Still Believe in Christmas' Crowns Christian Airplay Chart