Gone Girl Is Turning 10! Read a Never-Before-Seen Passage from Gillian Flynn's Book Before Anniversary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

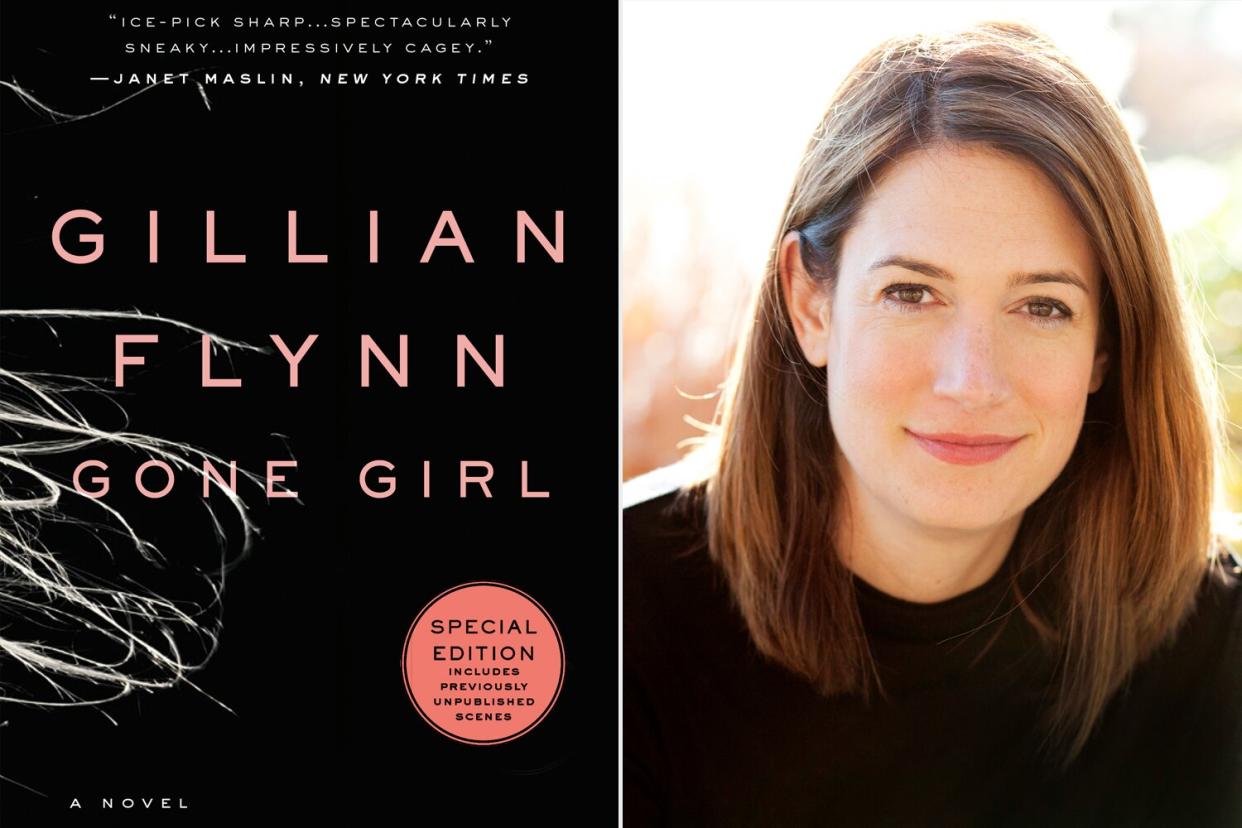

courtesy of Penguin Random House; Heidi Jo Brady

Happy 10th anniversary, Nick and Amy!

Gillian Flynn's bestselling psychological thriller Gone Girl debuted on June 5, 2012, revamping the genre with a despicably unreliable narrator and one bitingly memorable twist. The book was then made into a hit movie by director David Fincher in 2014 starring Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike.

To commemorate a decade since the release, Penguin Random House is unveiling a special anniversary edition that includes never-before-seen passages written by Flynn, PEOPLE can exclusively reveal.

"I'm really thrilled to ring in the 10-year anniversary of Gone Girl with a look at how this novel ever started — I wrote at least three books figuring out what, exactly, I was writing," Flynn said in a statement.

"I'm excited (and mildly nervous) to show readers a behind-the-scenes look at how Gone Girl evolved, and especially my early version of Amazing Amy Elliott. She's not quite the final Amy — but it's clear she has always been her acerbic, insistent and very own self."

Read on for an exclusive sneak peek of the new materials before the reissue hits shelves Tuesday, May 31, wherever books are sold.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from juicy celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

Merrick Morton/20th Century Fox/Regency/Kobal/Shutterstock Rosamund Pike as Amy Dunne in Gone Girl (2014).

AMY ELLIOTT DUNNE

I'll be the first to admit that I can be a bit needy. Clingy. Demanding, sometimes. Of course, some of that neediness is not my fault. Even Nick says my parents should take a good chunk of blame. I was raised like a little dauphiness, a sun queen, and my court, those obliged to serve me, included my mother and father and anyone else who came into range. That's not how it should have been, but that's how it was. Each morning, my parents would come in together to wake me, gently nuzzling my cheek, and when I opened my eyes, they would leap back with thrilled grins and rain-patter claps. No child should consider the mere act of waking to be laudable.

I was a child in a busy house of grown-ups: a cook, driver, gardener, nanny, and tutors and instructors for everything from French (le mieux, c'est de commencer jeune) to riding. (Unlike most girls, I never really took to horses; I found them powerful but neurotic, willful but skittish. Maybe they reminded me of me.) I was imperious with the staff but wary around other children, who apparently had not read the memo about my ascension. Children, in fact, baffled me. They could not be brought to heel. They never listened to reason. I must say, the truth is, I was simply a lot brighter than other children my age. I spoke the language of adults, of if this, then, that my cohorts had yet to learn.

I still remember my parents briefly, idealistically considered enrolling me in public school — they thought a few years with regular kids might be sort of a reverse polishing school for me. The Averagization of Amy. And, in truth, we lived north of Chicago in one of the wealthiest suburbs in the country, so the public school there wasn't exactly public school. I mention that only for context; I'm not overly impressed with my wealth. It's simply a fact, like the color of my eyes. But the story: I was getting ready to start third grade, and the local public school was testing my language skills, making sure I was at the correct level. The question was: "Complete this sentence: Double, double, toil and . . . and then a series of words that might rhyme. I didn't need them. Good little scholar that I was, I blurted out, "toil and trouble, fire burn and cauldron bubble." And I remember the teacher jumped back, like she was burned. She had to double-check a book to make sure I was right, and she pulled another teacher over and said, "Say what you just said to me," and I did, and added, "It's Shakespeare." It was just something my parents said. They are literate people, and sometimes they just throw out great lines like that. The way some couples have a special whistle or a look or whatever, my parents quote poetry.

RELATED: Gillian Flynn Says Gone Girl's Nick & Amy Would Not Have Survived Quarantine Together

A lot of people, by the way, screw that line up. After the real estate you-know-what burst, I started collecting headlines that read: Bubble, Bubble Toil and Trouble. How incredibly stupid. They're suggesting the quote goes: Bubble, bubble toil and trouble, fires burn and cauldrons bubble. I really don't think Shakespeare, the greatest writer who ever lived, would rhyme bubble with . . . bubble.

I didn't go to public school after all.

I went to an all-girls private elementary school and then to boarding school, all-girls. The elementary school, no matter how private, didn't work for me. I was still smarter, more mature, a little more . . . I don't know, can one say classy to describe fourth graders? It wasn't like I necessarily had more money — we all came from the same township, where every street features a series of stone gates, which guard ballpark lawns, which lead to Tudor mansions or French Norman manors or stately brick Georgians, all with views overlooking the expanse of Lake Michigan. It really was like growing up in a fairy tale. But it was Chicago. Even if it was the poshest zip code in the Midwest, it's still the Midwest, and the parents were more concerned about the proper clothes and cars for their children — the easy stuff — than the life of the mind, which was very much how my parents wanted me raised.

My father is a psychologist, Harvard-trained; he created the Elliott Behavioral Industrial Cognitive Test, best known as simply the Elliott Test, so he is a thinker and a goal-setter. My mother, as I mentioned, reinvented feminism. Together, they created a test that has been a proven indicator of whether a relationship will work. Designer labels don't interest them; they have bigger things going on. So in elementary school I was still different, a little apart, the most popular girl — I'm not just saying that, I was voted that — but also the loneliest. I think if the girls hadn't been swayed by my charisma and leadership skills, if they'd voted for simply whom they liked best, it would have been Jennifer Foss. She wasn't the smartest, and she was not beautiful, but she was incredibly outgoing and she never seemed self-conscious. She was just nice to everybody, and not in a puppy-dog-love-me way, but genuinely. Genuinely nice, genuinely upbeat. I always admired her, and I still think of her every now and then. Jennifer Foss. I bet she's happy. She seems like the type.

Excerpted from the book GONE GIRL by Gillian Flynn. Copyright © 2022 by Gillian Flynn. Published by Ballantine, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.