“It’s Going to Take Hip-Hop to Save Us”: Allen Hughes on Menace II Society, Tupac, and Racism

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The post “It’s Going to Take Hip-Hop to Save Us”: Allen Hughes on Menace II Society, Tupac, and Racism appeared first on Consequence.

The 50th anniversary of hip-hop may have technically passed (August 11th, 2023), but we’re commemorating the landmark all month long. Today, we speak with Allen Hughes, an early pioneer in the world of hip-hop and film. Keep an eye out for all our Hip-Hop 50 content throughout the month, and check out our exclusive merch featuring our Hip-Hop 50 design at the Consequence Shop. A portion of proceeds from sales benefits Chance the Rapper’s SocialWorks.

Director Allen Hughes has a lot of faith in the power of hip-hop. “Without hip-hop, we clearly don’t get Barack Obama,” he tells Consequence via Zoom. “We clearly don’t get Black Panther — because John Singleton was trying to make Black Panther 30 years ago and couldn’t get it off the ground. Without hip-hop, there’s a lot that doesn’t happen, but it’s going to take hip-hop to save us from these degenerate pieces of shit that are trying to make racism pop again.”

He says it’s up to hip-hop artists to “wake up and say something,” as he’s afraid creators of all sorts have strayed away from vocal activism in recent years. “You could say what you will about Tupac’s last 11 months with Death Row, but at least his first 24 years, he was saying something and he stood for something,” Hughes says. “Right now, outside of Kendrick Lamar and a handful of others, there’s no one’s really saying anything or standing for anything. And by the way, I mean that of our celebrities in general. You see what’s going on again with Roe v. Wade. You see what’s going on with voting rights. You’re like, where are the leaders in the celebrity space? No one stands for anything anymore, and everyone’s scared.”

It’s a comment that comes towards the end of a lengthy conversation about Hughes’ history as a filmmaker as well as his most recent project, FX’s Dear Mama (available to stream now on Hulu). The Emmy-nominated docuseries chronicles the life of Tupac Shakur, with whom Hughes has a complicated backstory — but the end result is a tribute to a legend, from an artist whose history with both hip-hop and film goes back a long time.

“You Can’t Be Something You’re Not”

Hughes tells the story of when he and his twin brother, Albert Hughes, discovered the power of film with the flair of an accomplished storyteller. “Me and my brother were 10, and our babysitter took us to see this movie, this period piece, with her boyfriend. We were kicking and screaming, like, we don’t want to see the fucking period piece… and when that boulder rolled down and chased after Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark in 1981, we were like, holy fuck, what? That was the moment we wanted to become filmmakers.”

Right away, he says, “we would take Polaroid cameras and act like we were making movies. And then when my mother started making some money, she bought us a camera when we were 12, and that was all she wrote. That’s all we did, was learn how to make movies.”

The Hughes’ rising interest in film happened to coincide with how hip-hop, in 1984, was starting to break through with artists like Run-D.M.C. and LL Cool J. “Some of my earliest movies, even in high school… because it was video, we didn’t do serious stuff back then. We would take like something like Miami Vice and we would do a send-up on it and call it Compton Vice and completely make it hip-hop. So hip-hop was always there, and film was there from the beginning.”

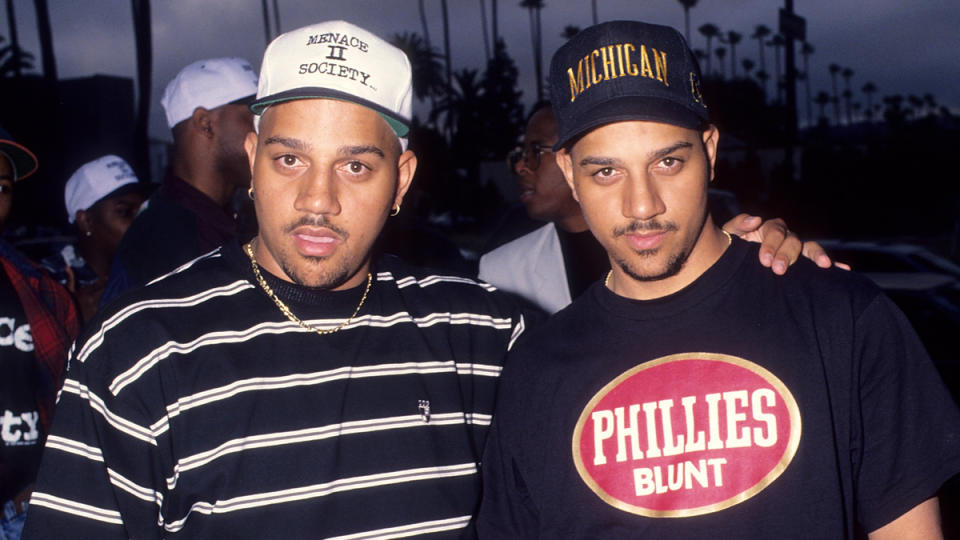

Allen Hughes Albert Hughes at the Menace II Society Premiere, photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

It was Allen who focused on the music of the Hughes Brothers’ films, assembling hip-hop soundtracks that went multi-platinum. “Even when we did American Pimp [a 1999 documentary about underground pimp culture], it was chock full of all those classic R&B hits that hip-hop samples. It’s just who you are. You can’t be something you’re not. It’s just who you are. It was never a conscious thought.”

Hughes points out that starting in the early 1970s, Black films like Superfly, Shaft, and Trouble Man were bringing R&B to their soundtracks. “Marvin Gaye is literally rapping on [the Trouble Man theme],” he says, paraphrasing his way through the lyrics. “I’ve been to places, I’ve seen some places… I can’t do the lyrics, but that’s hip-hop. He’s rapping, right? That’s 1972.”

From Hughes’ perspective, hip-hop and Black films are thoroughly entwined, though he does note that in the 1990s, movies like Waiting to Exhale “weren’t talking about bitches and the hoes and fucking and sucking and R&B songs. Let’s call it sexy R&B Black film. And then hip-hop did something that no other medium and art form in the history of mankind and womankind did, which is it completely consumed everything in its path. Completely consumed it. It became the number one selling genre music because it literally envelops everything in its path. Nothing can survive hip-hop’s path, because it just adopts it. So R&B became hip-hop. Rock became hip-hop. Country became hip-hop. You can’t compete with that.”

Menace II Society, and “Hip-Hop Energy”

As a directing team, the Hughes Brothers moved up the ladder similarly to other filmmakers of the era: short films, followed by music videos for Tone Loc and Tupac Shakur (we’ll get to that), which led to their feature debut.

Hughes considers himself grateful that he and his brother only worked in music video for less than a year, because “if you stay in music videos, you develop a tremendous amount of bad habits that won’t help you in long-form narrative. It’s like taking a sprinter who’s been running and making them a marathon runner. It’s two different things. So we were blessed enough to be given an opportunity in hip-hop music videos and the urgency that came with that back in ’91, where there were still stories in the music. And then we were fortunate enough to get out after only a year of doing it — because we never saw music videos as the destination. That was like a means to an end. We always wanted to do feature films.”

That said, looking back on the brothers’ theatrical debut, Hughes admits, “We have a lot of problems with it. We never liked the film. You could see what worked about the film — that’s hip-hop energy. And it’s probably the first time in the history of major motion pictures that the lunatics were running the asylum as well, because we’re 19 and 20 directing a film about 19 and 20-year-olds. There is no filter, and it’s hectic.”

Menace II Society, which turns 30 this year, is told from the point-of-view of Caine (Tyrin Turner) as he and his friends descend into a life of crime and violence in South Central Los Angeles. The movie made a huge splash upon its premiere, bringing the Hughes Brothers to both the Cannes Film Festival and the attention of Hollywood, and opening the eyes of white audiences

Hughes says, in fact, that white audiences are who the film was made for. “We said that back then, because I remember Siskel and Ebert gave Spike Lee a funny review, and Spike’s response was appropriate — he goes, ‘I don’t make my films for you guys.’ I thought that was incredible, but by the time we got to Menace, the whole reason why we made it was we knew that other people outside of the Black community didn’t understand why these kids got like this. They just saw them as animals. That’s the way the media treated Black people — Cops every week. So we were like, ‘Wow, if we can get white people to understand that this is actually a child, this is actually a human being that, because of a set of circumstances, has done these things, then that’s a win for us.'”

And sure enough, it worked. “When that movie came out, so many white people would grab me and go, ‘I just didn’t understand.’ Me and my brother may have problems with Menace, but the result was exactly what we wanted. People really did feel it. They really did understand things they didn’t understand before. So that was really rewarding in that regard.”

Speaking His Truth About Tupac

Hughes is currently an Emmy nominee for Dear Mama, his five-part FX docuseries about the life of Tupac Shakur, in which Hughes himself is also a minor character… reluctantly. In 1993, Hughes was assaulted by the rapper and others following a dispute over Shakur not being cast in Menace II Society — Shakur was convicted of assault and battery for the incident, and the two men never reconnected despite a public apology.

“For the record, Tupac didn’t beat me up; ten other motherfuckers beat me up,” Hughes clarifies off-screen to Snoop Dogg during a Dear Mama interview.

Hughes says his fellow producers pushed him to go on camera to discuss those events, because while he knew the series would have to deal with it, “I kept saying, I’m not doing it, I can’t cross that line. I don’t like when filmmakers put themselves in the film. I don’t want to be thinking about the filmmaker — what I like about her or him, or not like about her or him. That just gets in the way. And quite frankly, I don’t want to be famous. I had a little bit of that early in my career with my brother, when we came out with Menace II Society — it was like, I don’t want to be that guy. And you want to focus on the subject. You want to focus on the filmmaking.”

In the series, you see his reluctance plain as day when he’s interviewed about those events, and he says that he blacked out while that footage was being filmed. “I’m just speaking my truth, and I don’t remember what I said. I had to recuse myself from that part of the edit.”

He instead focused on exploring Shakur’s story, especially how the circumstances of his early life affected him. “I didn’t realize the abject poverty, and what it does to the psyche and how it affects a young child, no matter how talented you are. And to see how that lingered with Tupac, and was like the albatross that he was always grappling with… The paranoia, I thought, came from just being a young Black male and smoking weed and getting persecuted by the cops. But to see that the feds were after his family from the moment he came out, the moment he was born, and what the FBI COINTELPRO program did to his entire family… The poverty plus the persecution and the FBI just dismantling his whole family was a complete surprise to me.”

Why Hip-Hop May Never Get Its Due

Having observed the rise of hip-hop from its earliest days, Hughes has a “massive problem” with the way it’s perceived in our culture. “I think white people look at jazz and that’s the medium where they go, ‘Oh, what an artist. We can only hope that we can play with them someday,’ or whatever. I think hip-hop will always be the red-headed stepchild. Always. I don’t care. Even though it’s the number-one-selling art form in the world right now, just like our voting rights and the right to choose and affirmative action, there’s never a moment where you’ve actually arrived. It’s always going to be undermined somehow.”

Continues Hughes, “I hate to sound pessimistic. I think the exciting thing is there’s never been more opportunity for people of color and film and television. And there’s never been so many shows and films out there. And I don’t think that’s going to go away like it did in the ’90s.”

Plus, Hughes notes, recent years have seen the end of a long-standing perception that Black films might be successful in the United States, but won’t be as successful internationally. “You see it literally in the case where you sit the Black character at the Marvel franchise table — it does a billion dollars when you give it the same resources. So you can’t say [‘Black doesn’t travel’] anymore.”

That said, he adds, “There’s this thing in our country and it just is what it is — good ol’ fashioned racism. It’s why I made Dear Mama. It’s always going to be here in some form. Unfortunately for us all, there’s a large group of people trying to erase the fact that slavery even happened. So you’re like, wow, we barely were getting to the point of just having a conversation and the come-to-Jesus moment, which is 400 plus years in the making — and we can’t have that conversation.”

Hughes says that “I love when white kids and Asian kids and Indian kids take hip-hop on, because it’s meant for everyone. That’s wonderful.” However, he continues, “Do I think a uniquely Black art form, that some consider the last great art form of the 20th century, is ever going to get its just due? Fuck no. And by the way, that’s what makes it punk rock. No matter how popular it is. The thing that’s gonna keep it and make it always be true to what it is, is that it’ll always be treated like a stepchild. And a stepchild will always be trying to overachieve — and will overachieve.”

FX’s Dear Mama is streaming now on Hulu, and new subscribers can get a free 30-day trial by signing up here.

“It’s Going to Take Hip-Hop to Save Us”: Allen Hughes on Menace II Society, Tupac, and Racism

Liz Shannon Miller

Popular Posts