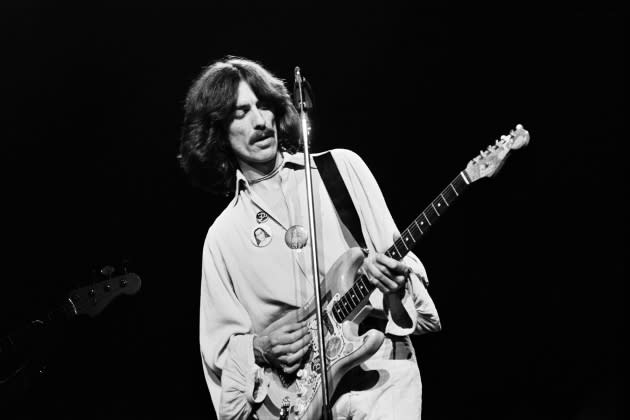

How George Harrison’s 1973 Album ‘Living in the Material World’ Went From Reviled Dud To Sleeper Masterpiece

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1973, the world saw George Harrison as the Beatle who was winning the break-up. He became a solo superstar with All Things Must Pass, his big triple-vinyl extravaganza, then his noble and star-sudded Concert For Bangla Desh. He’d finally broken free of the Fabs and gotten everything he’d ever wanted. Right? Well, not exactly. George stripped it all down for his sleeper masterpiece: Living In The Material World, released 50 years ago at the end of May 1973. It’s the most profoundly weird album of his life.

Over the years, Living in the Material World got a bad reputation as a preach-and-screech mess. Like Paul McCartney’s Ram, which was universally despised for decades, Material World was sitting on the rubbish heap until modern indie-rock hipsters discovered it and realized it was genius. Time has finally caught up with it.

More from Rolling Stone

How Robbie McIntosh Became a Go-To Guitarist for Paul McCartney, John Mayer, and Others

Dolly Parton's 'Rockstar' Has a Feature by Literally Every Rock Star

Paul McCartney, Noel Gallagher Remember Artwork 'Golden Age' in 'Story of Hipgnosis' Trailer

It doesn’t have the uplifting appeal of All Things but that’s the point. All Things is an Ex-Beatle making a Big Spiritual Statement. Material World is the album of a very confused, prematurely bitter, slightly deranged dude about to turn 30, wondering why his life is no fun after his success. He sees betrayal and paranoia all around him. No wonder it sounds realer than ever in 2023.

George turns his spiritual crises into candid, conflicted, totally self-contradictory songs. It’s got some of his least likable moments, along with some of his most beautiful. He never sounded like such a paradox. And he never sounded so unguarded, revealing himself in ways he never did before and never would again. His brash confidence has taken a beating. (But look on the bright side—at least he’s got his wife Pattie Boyd, and his best friend Eric Clapton. What could go wrong?)

George steps back from the epic scale of All Things Must Pass. It’s a band album, with the second-best band he ever had. It’s just a core of trusted mates: Klaus Voorman on bass, Jim Keltner on drums, Nicky Hopkins on piano, Gary Wright on organ. The sound is intimate, human-scale, with the gorgeous simplicity of “Be Here Now,” “Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long,” and the Number One hit ““Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth).”

George produced himself for the first time, stretching out on slide. He even went back to the sitar, the instrument that started him down his spiritual path, but one he hadn’t played in years. It’s his proto-indie-rock singer-songwriter album—it says a lot that the most famous remake of these tunes is Elliott Smith’s version of “Give Me Love,” which nails the melancholy spirit. “The Day The World Gets ‘Round” has a weirdly specific Pavement vibe, evoking Wowee Zowee or Brighten The Corners.

The heart of the album is “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth),” one of the most beautiful songs any of the Beatles ever wrote, before or after the break-up. This is the tune that distills all George Harrison’s genius, all his torment, all his profound yearning and disenchantment and hope, into a few sparkling minutes. And he elevates everyone in the room. Did Klaus Voorman ever sound so transported on bass? Did Nicky Hopkins ever sound so blissed-out? Did any guitar ever sound so happy to be in George Harrison’s hands? George had special affection for “Give Me Love” in his memoir I Me Mine. He wrote, “This song is a prayer and personal statement between me, the Lord, and whoever likes it.”

But it’s easy to hear how Material World went on to become infamous. George can’t knock it off with the cosmic bullshit. It’s full of preachy pomp and coked-out hypocrisy, side by side with moments of human warmth. George hectors fans to be more considerate of God’s feelings, but he makes his version of God sound ridiculously cheap and petty, like a Real Housewife whose pills are wearing off. (“The Lord Loves The One That Loves The Lord”? What are you, Lord—twelve?)

George was in low spirits at this point. For all his religious moralizing, his private life was sex-and-drugs chaos. After his hard work for the refugees of Bangla Desh, he felt betrayed. The funds got bungled by the money men he’d trusted, leaving him on the hook for a million pounds in taxes. Then there was his never-ending Beatles legal mess, which inspired “Sue Me, Sue You Blues.”

But on the most personal level, his beloved mother Louise died in July 1970. She got cancer at the same time the Beatles were falling apart. He never mentions her name here, but you can hear her loss all over the music, especially “Be Here Now,” the sound of a grief-ravaged son, mourning with the simple mantra, “It’s not like it was before.” Like John in “Julia” or Paul in “Let It Be,” he made some of his most soulful music out of maternal loss, in his hour of darkness.

Note: In 1970, the year Mrs. Harrison died, the Beatles released “Let It Be,” John released “Mother,” and Ringo released Sentimental Journey, a album of the alive-and-well Elsie Starkey’s favorite oldies, explaining, “I did it for me mum.” These boys were always brothers, even when breaking up.

But George gets a spiritual boost from his band, especially piano man Nicky Hopkins. If George Martin was the Fifth Beatle, Hopkins was the Fifth Solo Beatle, the session guy who played with all four of them, turning so many good songs into great ones. He’s an essential teammate all over Imagine, Ringo, and Material World, playing his trademark “diamond tiaras,” as Mick Jagger called them.

“Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long” is a dazzling gem—George might have been done with his Phil Spector era, but this is the most Phil Spector thing he ever did, a classic piece of Sixties girl-group pop worthy of the Crystals or the Ronettes. He lovingly nails every detail: those dramatic drums in the chorus, the harpsichord, even the “Be My Baby” castanets. George was always a devout worshipper of the girl-group queens—what people missed about “My Sweet Lord” was that there was nothing accidental about his riff on the Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine,” because George’s belief in the Chiffons was as intense as his other spiritual beliefs. It’s the album’s purest love song.

Ronnie Spector’s spirit is also in “Try Some Buy Some,” a beautifully bizarre waltz he originally wrote for her 1971 comeback single. As Ronnie wrote in her memoir Be My Baby, she told him, “I don’t understand a word of it.” He replied, “That’s okay. I don’t either.” One of the song’s biggest fans: David Bowie, who sang it on his 2003 album Reality, hearing it as an allegory of drug addiction and recovery.

“Be Here Now” is the kind of title that might make you suspect the worst, but it aims for the heart with minimal lyrics, the song that feels most like an elegy for Louise Harrison. His sitar adds a haunting Indian drone effect, but it’s also a Southern California song, with the folk-rock vibe of “Blue Jay Way” or “Long, Long, Long.” He wrote it in the Hollywood Hills, with a tinge of Neil Young in the guitar.

As a wonderfully comic postscript, “Be Here Now” turned into the title of one of the druggiest rock albums ever made, the 1997 Oasis mega-flop that did for cocaine what this album did for Krishna. Even funnier, Noel Gallagher had the gall to credit the title to John Lennon, a claim designed to keep George far away from joining Paul in any Noel photo opps. (George got it from Baba Ram Dass’ book.) But it was fitting, since Noel named Oasis’ greatest hit after George’s 1968 film soundtrack: Wonderwall Music.

In another piece of pop irony that George must have appreciated, “Living in the Material World” became most famous as the hook for one of Madonna’s most iconic Eighties hits, right before George produced her 1985 movie Shanghai Surprise. “Material Girl” had a very Beatles spirit of cheeky humor—the narrator could be the girl from “Drive My Car.” But Madonna ended up on her own George-like spiritual journey, going from “Material Girl” to Ray of Light in 13 years, the same timespan George took from Hamburg to Material World. All things must pass, indeed.

Yet “Material World” is George confessing he feels like a prisoner in his own life. “Can’t say what I’m doing here / But I hope to see much clearer,” he sings, with no hope in his voice and not even an attempt to fake it. He vows he’s “trying to get a message through,” even though his only message is that he’s desperately looking for a message. But his only human connection is—surprisingly—his old Beatle buddies. He sings, “Met them all here in the material world / John and Paul here in the material world / Though we started out quite poor / We got Richie on a tour.” There’s something vulnerable about how he calls Ringo by his childhood name “Richie,” especially with Ringo right there playing drums.

The delightful B-side “Miss O’Dell” should have made the album. George gossips about his old friend and Apple comrade Chris O’Dell, laughing too hard to sing the second verse, over Jim Keltner’s cowbell hook. In one take, he casually drops the phone number “Garston 6922,” which happened to be Paul’s old number from back home in Liverpool. It’s the closest this album could have come to the breezy rock & roll fun of “Apple Scruffs” or “Wah Way.” But it was too light-hearted for what George saw as his mission.

But George’s mystique took tumble a year later with Dark Horse. You could make a case it was the worst solo Beatles album up to that point—at least John and Yoko’s Wedding Album can make harmless background listening for doing the dishes. Dark Horse was just a boozy pity party, recorded while he had a nasty case of laryngitis. He was also suffering from “Layla”-itis, since Pattie finally left him for Clapton. George was civilized in public, telling a press conference, “I’d rather she was with him than with some dope.” But he was in no shape to make music, as he sadly showed in his hyped 1974 solo tour. It wiped out the good will he’d won before, and Material World became collateral damage.

Over the years, it got overshadowed by All Things. Even hardcore Beatle fans came to shy away from this one. The critic Robert Christgau summed it up the case against it with typically acerbic wit: “Harrison sings as if he’s doing sitar impressions, and four different people, including a little man in my head who I never noticed before, have expressed intense gratitude when I turned the damned thing off during ‘Be Here Now.’”

So much light and life came back into his music after he met his wife Olivia Arias. He crafted some of his best tunes in the 1970s—“Oooh Baby (You Know That I Love You)” on Extra Texture, “Blow Away” and “Here Comes The Moon” on George Harrison, (especially) “Pure Smokey” on Thirty Three and a Third. When his career rebounded in the late Eighties, people were so grateful to have George back, they decided to forgive and forget most of his 1970s output after All Things Must Pass. But that meant sleeping on some great music. And Living in the Material World is full of George Harrison moments worth rediscovering.

Best of Rolling Stone