How George Carlin Made Us Grateful for a Life Worth Losing

Music, Movies & Moods is a regular free-form column in which Matt Melis explores the cracks between where art and daily life meet. This time, he explores how George Carlin’s recent posthumous album helps reveal the humanity behind the comedian’s darkest material.

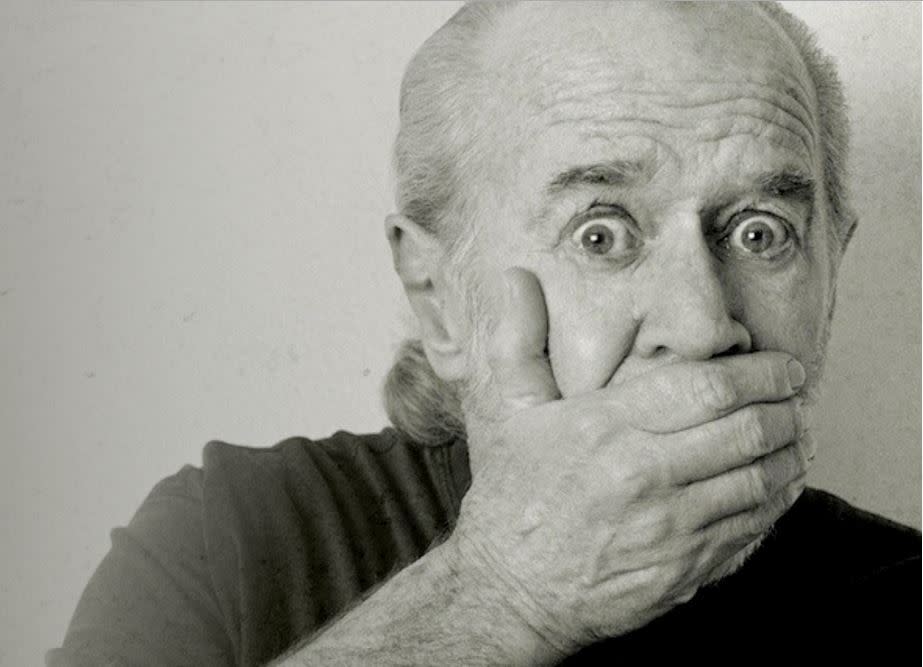

Late March 1996. The Beacon Theater in New York City. George Carlin, already a comedy legend, silver-haired and dressed entirely in black — long removed from his clean-cut beginnings and his hippy disc jockey phase — walks onstage for one of two recorded performances that will yield his Back in Town album and accompanying HBO special. He silences an ecstatic audience with a single question as only George Carlin could: “Why is it that most of the people who are against abortion are people you wouldn’t want to fuck in the first place?” He delivers the observation like a giddy child tugging at his mother’s sleeve, one who’s been repeatedly told not to interrupt the grownups but is far too excited about his latest naughty impulse to remain hushed. And just like that, Carlin ushers us across “the line.”

This slam on the sex appeal of pro-lifers came several years after Carlin had begun developing the comedic voice that would carry him through to his death in 2008. “I sort of gave up on the human race,” he told Charlie Rose in 1996. “That gave me a lot of freedom from a distant platform to watch the whole thing with a combination of wonder and pity.” It’s a stance that liberated Carlin to mine the taboo, perverse, and macabre for laughs in a way that few other comedians have ever dared. However, the goal never seemed to be shock value for its own sake but rather to subvert the political correctness that labels certain topics as out of bounds. “People bring these amorphous things called values to the theater,” he explained to Rose, “and I like to find out where their line may be and deliberately cross it … and make them glad they came.” And millions — while attending a show, watching a television special, or listening to an album — have experienced that ambivalent moment when Carlin touched a personal nerve and pushed beyond our comfort zones — maybe performing a piece on rape, suicide, or natural disasters – only to somehow have us laughing a few seconds later. Or, as he put it, glad we came.

It’s been nearly a decade since Carlin last coaxed us across that line of decency. In late September, the comedian’s estate released his first posthumous album, I Kinda Like It When a Lotta People Die. While we’ve grown accustomed to musicians releasing more records from the grave than while alive, the concept of posthumous albums sounds like something Carlin might’ve developed into five minutes. It’s easy to imagine him ranting, “You think I’ll have nothing better to do when I’m dead than tell jokes to you alive motherfuckers?” The bulk of this unreleased material comes from Vegas shows recorded on September 9th and 10th, 2001. Given the next day’s terror attacks, Carlin shelved the title and recorded mostly new material that November for Complaints and Grievances. The title got scrapped again in 2006 due to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, this time in favor of the comparatively upbeat Life Is Worth Losing. Though he’s promised there’s no afterlife and that even if there is, our dearly departed have more important shit to do than spend all day smiling down at us, part of me likes to believe Carlin knows his darkest title has finally seen daylight.

Carlin wasn’t always so dark, though. He hadn’t always made lists of people who ought to be killed, pitched albums of songs about terminal diseases, or, as he put it, indulged in “the kind of thoughts that kept [him] out of the really good schools.” At his very best, Carlin masterfully dissected, unpacked, and turned our modern language on its head as no linguist, let alone stand-up, has ever done before or since. Like many, I got introduced to his comedy by my parents. One afternoon, my father, a sports fan, called me in to watch his favorite bit, “Baseball and Football”. I’ll never forget that first time hearing Carlin practically float across the stage as he theatrically emphasized how lighthearted and carefree the lexicon of our old national pastime seems alongside that of our new one. Later, when I finally snuck a listen to “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” (shit, piss, fuck, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker, and tits, if you’re wondering), I quickly moved beyond the impish thrill of hearing those words “that’ll infect [my] soul” and marveled at how Carlin playfully plucked them, twisted them, and turned them on themselves. I may have been too young to really understand about the arbitrariness of words or how people bestow certain powers upon some of them, but I did understand that something very funny — and maybe even important — was going on.

That innate love of language never waned as Carlin turned to more esoteric and grim fare later in his career. Amid grumblings on abortion, God (or maybe Joe Pesci), and bits of things that come off your body, he continued to mix in poetic, rapid-fire pieces, such as “Advertising Lullaby” and “A Modern Man”, that call attention to the hollowness and impotence of jargon, buzz words, and modern-speak. By the time I rediscovered Carlin as a teen, he had long since made a personal target of euphemisms, “that soft language that takes the life out of life” and hides the fact that people are getting royally fucked over — often without lubrication. According to Carlin, our educational system itself admitted it was losing ground by shifting policy from “Project Head Start” to “No Child Left Behind.” It’s all right there in the lingo. And after he traced the evolution of the term “shell shock” from its post-WWI origins to its bloated, obfuscating, numbing modern form, “posttraumatic stress disorder,” it was hard not to agree with his conclusion that veterans might get looked after better if the condition was still called shell shock. To this day, I can’t so much as write an email without feeling like Carlin is looking over my shoulder ready to call bullshit.

But for all of Carlin’s enduring allegiance to pointing out the truth behind the volumes our language speaks, fails to say, or intentionally hushes, that doesn’t explain how the guy who turned the concept of “Stuff” into a classic comedy routine of my youth had graduated (deteriorated?) to programming “sweeps” month for “The All-Suicide TV Channel” by the time I was in the market to purchase my own cable package. By that point, even Carlin’s explanation of “the line” couldn’t really account for the darkness of his topics — he’d long ago blown past that original demarcation, erasing and redrawing it with each new batch of material. Shortly after Carlin died, fellow east coast stand-up Louis C.K. shed some light on the late comedian’s process. He explained that Carlin worked through a cycle where he would write jokes, develop his hour on tour, record an HBO special, and then dump all his material and start again fresh. The result is he forced himself to explore places a comedian might not otherwise go. “When you’re done telling jokes about airplanes and dogs, what’ve you got left?” C.K. explained. “You can only dig deeper. Start talking about your feelings and who you are, then your nightmares and fears, and then you just get into some weird shit.” When thinking of Carlin’s career in those terms, maybe the question isn’t how he ended up joking about teenage boys strangling themselves during masturbation to intensify orgasms. Maybe the real question becomes where the fuck would he have gone next?

I was fortunate enough to see Carlin perform twice in 2004 leading up to his Life Is Worth Losing special, once in Pittsburgh early in the tour and again several months later in Indiana. Part of the joy was seeing how his material and performance evolved over those months (for instance, seeing him read “A Modern Man” from a script in Pittsburgh and have it down pat by the time he rolled through West Lafayette). But equally interesting to me was watching a handful of people leave the theater at the same point during both shows: the suicide portion. That was a new experience for me. I had seen audience members leave films, concerts, plays, and ballgames before in response to a terrible, or even unbearable, screening or performance. But apart from maybe a parent realizing they didn’t agree with the rating on a film they had taken their child to, I had never before witnessed people leaving a theater because they were sincerely offended. I wondered if they would’ve been glad they came had they stayed a little longer, or are some subjects just not funny?

Much of Carlin’s darker period naturally raised those types of questions: what’s okay to joke about, what’s funny, and what’s alright to laugh at? After all, years before Donald Trump got in trouble for bragging about grabbing pussies, Carlin proposed harvesting them from corpses — and he knew he was miked. On his 1990 album, Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics, Carlin spoke frankly about these issues in a piece called “Rape Can Be Funny”. To his thinking, anything can be joked about given the necessary context or exaggeration. It’s why we can laugh about something as cringe-worthy and demented as “Posthumous Female Transplants” but never about, not even in a locker room with Billy Bush, a prospective President of the United States of America with a history of misogyny and male chauvinism and mounting allegations of sexual assault saying he gets away with groping women. There’s no exaggeration there — no separation from reality that allows us to find humor in an unlikely place. It’s why I wonder if people who walked out on those two Carlin shows might have actually laughed had they stayed. While Carlin used suicide as the framework, the pieces in question, “The Suicide Guy” and “The All-Suicide TV Channel”, actually turn out to be about the tedium of getting things done (could’ve been about cleaning the gutters on a house) and, on the latter, how Americans are dumb enough to watch anything on television. It’s a perfect example of bringing us warily across that line and leaving us surprisingly glad we came.

Among the treats on I Kinda Like It When a Lotta People Die is “Uncle Dave”, an earlier version of what would later appear as “Yeast Infection/Coast-to-Coast Emergency” six years later on Life Is Worth Losing. In the piece, Carlin talks about how much he enjoys massive death tolls and goes on to give a “concrete example” of the type of natural disaster he secretly roots for: a rapid-fire account that begins with a downtown water main breaking and ends with a split in the space-time continuum where the hatred and bitterness of Carlin’s dead Uncle Dave, my Uncle Dave, and all of your Uncle Daves causes another big bang that leads to a million stars, a million planets, and millions of happy Uncle Daves. Some of the details are different from the final version, but the beats are mostly the same, as is the twist that Carlin’s sick, heartless desires ultimately have good intentions behind them. However, in the 2006 version, Carlin changes the pace and tone of the piece’s climax. He slows down and grumbles as he relates Uncle Dave’s bitterness and turns sweet and avuncular as he describes the disaster’s happy aftermath. He lets the piece breathe and really sink in with the audience. This strange, escalating tour de force always had something deep to say about our ability to be better than we are, but it took Carlin several years to learn just how to say it. With these changes, “Uncle Dave” became not only Carlin’s last great performance piece, but also a glimpse at the humanity behind the man in black with all the angry complaints and disturbed notions.

Late in life, Kurt Vonnegut, arguably America’s finest satirist, wrote that he feared he might never be funny again — that a lifetime of observing human cruelty, greed, and thoughtlessness had finally done him in, stripping him of the capacity to be humorous or even acknowledge humor while digging through humanity’s rubble. Vonnegut’s sentiment has always reminded me of Carlin, not because the comedian ever talked about losing his ability to be funny or ever stopped making us laugh, but because I often sense that same tinge of disappointment in so much of his work. On numerous occasions, Carlin said, “People are just wonderful as individuals. You can see the whole universe in their eyes if you look carefully.” But, as he went on to explain, we shed our individuality to get on with the business of daily life and, in groups, often lose our innate capacity to be honest, decent, and square with each other. When I listen to the closing moments of the final version of “Uncle Dave”, that disappointment hits me like a tree trunk battering ram to the gut. The piece isn’t about natural disasters or kinda liking when a lotta people die. It’s really about what could be versus what is: kindness instead of selfishness, tolerance instead of hatred, and compassion instead of callousness. It’s a reminder that we could do better if we ever chose to, and we can go on forever plugging into that “A instead of B” formula until we finally get a world that doesn’t leave us needing someone like Carlin to make us laugh about how fucked up everything is just to get through our days with our sanity intact.

“Now, do you see why I like it when nature gets even with humans?” asks a bowing Carlin at the conclusion of Life Is Worth Losing.

Yes, George, all these years later, we get it.