Geddy Lee on the Day He Was Fired From Rush

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

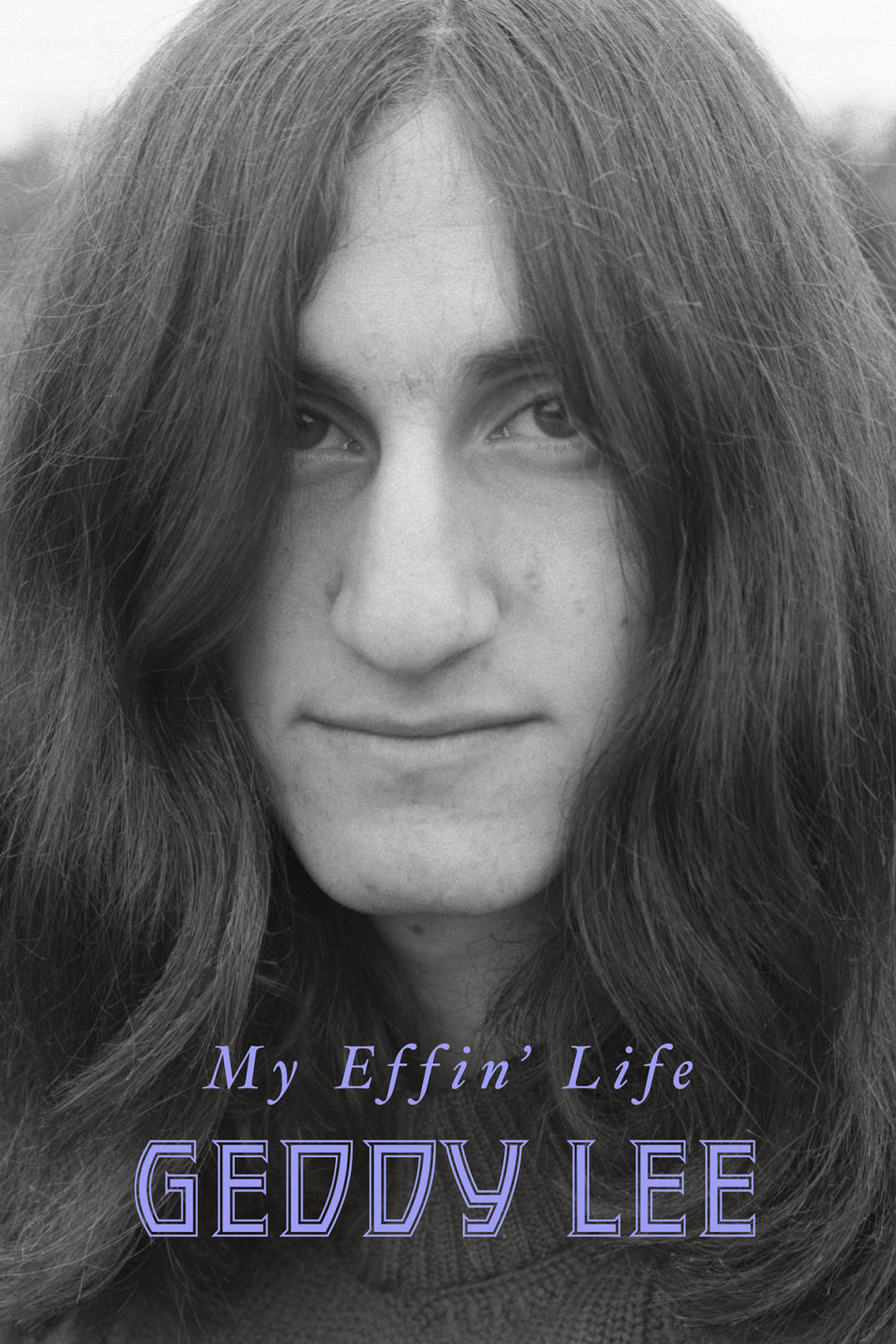

My Effin’ Life, the new memoir from Rush’s frontman and bassist, Geddy Lee, tells a tale that’s almost as epic in scale as his band’s largest-scale songs, from his upbringing as the child of two Holocaust survivors, to the rise of Rush, to the loss of drummer Neil Peart in 2020, and everything in between. In this exclusive excerpt, Lee takes us back to 1969, when an early, as-yet-unsigned lineup of Rush consisted of “Alex Lifeson, keyboardist Lindy Young, drummer John Rutsey, and me … until I am dumped.” (Lee spoke about his book and much more on our Rolling Music Now podcast; to hear the full interview with host Brian Hiatt, go here for the podcast provider of your choice, listen on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, or just press play below.)

More from Rolling Stone

'Coke Was Everywhere': Getting High During Neil Peart's Drum Solos, and More Geddy Lee Revelations

Geddy Lee Wants to Tour with Alex Lifeson: 'I Keep Working on Him'

Alex and John decided to bring on board a manager, a guy named Ray Danniels I’d seen around at various shows on the Yorkville strip and hanging around the coffeehouses. He was clean-shaven with blond shoulder-length hair that he was always playing with at the back of his head — and that he used to iron to keep straight. He’d left his home in Waterdown, Ontario, and, something of a hustler, earned his money however he could. He tried singing in a band, but that didn’t work out, so he set his sights on managing instead. When I first met him, he had his phone and his papers on the floor, which was basically his desk. His first agency was called Universal Sound, after which he formed the Music Shoppe, which in 1973 became SRO. He was ambitious, clever and a born salesman. Clearly, he saw something he liked in the band. But it wasn’t me.

So, one afternoon as I’m walking to rehearsals, I see Lindy coming towards me across the field on the way to his house, and I ask him where he’s going.

“Oh, hey, Ged,” he says, looking at the ground. “Uh, listen . . . Rehearsal is cancelled and, uh, well, the band is breaking up.”

Back home I got hold of the other guys, but they were weird and aloof on the phone. It seemed that Rush had disbanded, though I suspected I wasn’t being told the whole story. I tried not to dwell on it and started calling around to other musicians I knew, trying to get something else going, but then in May, I heard that Alex, John and Lindy had reformed as Hadrian (after the Roman emperor) with a new bass player named Joe. It was all a ruse. I’d been out-and-out lied to!

Ray had offered to manage them but made it clear he didn’t think I was right for the band. It’s important to say, however, that it turns out it wasn’t his idea in the first place. I’ve been informed some fifty years later that it was Rutsey’s. Just recently I asked Alex about that time—something I’d always wondered about but never really brought up. (Maybe I was afraid of the answer, I dunno.) He sheepishly responded that back then he was the kind of guy who just went along with things, and that the decision to replace me was driven by John, who was keen to reinvent the image of the band and wanted someone hipper . . . whatever that meant. “I didn’t want to get on John’s bad side,” he told me. “You know how he had a very strong personality. He made all the decisions. As for Ray, he was just being opportunistic.”

Whoever’s idea it was, the way they all went about it was deceitful and frankly chickenshit, and I was shocked and hurt. Still, I didn’t want to sit around and feel sorry for myself, so I said to myself, Fuck them, and resolved to start a band of my own. I’ve always pictured myself as a mousy kid, blowing with the wind and following the crowd, but the mysteries revealed when going back in time to write this book are, well, revelatory! I couldn’t have been entirely a will-o’-the-wisp or I would not have had the chutzpah to keep on keeping on. Clearly, music meant everything to me, and despite my supposed lack of confidence I instinctively knew that I had to take control of my own destiny, if only hoping that success would be a kind of revenge.

Like everyone, I suppose, I realize that over time I’ve forgotten or blocked out a lot of things. Even typing out the name Hadrian just now set a sort of fugue in motion. First my brain took me to the hike my wife and I took a few years ago from Bowness-on-Solway to Wallsend—along Hadrian’s Wall—when, trudging beside her, this memory suddenly presented itself: Hadrian was playing its debut gig at a local church, Willowdale United, and I’d been curious to hear the band. I’d gone to the show, but to do that I had to give up a pair of tickets for another, at Maple Leaf Gardens the same night. No big deal, really, it was only . . . the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Doh! What an idiot. I’d reckoned I could always catch them next time they came to town, but Jimi died sixteen months later.

Going to that Hadrian show was a mistake on another level too. It was no fun watching my former bandmates. They had a decent, fairly enthusiastic crowd, but their playing was sloppy. They didn’t really click, and Joe looked lost and struggling. Honestly, I took little pleasure in witnessing their mediocrity.

Meanwhile, I’d started a band of my own, playing songs by John Mayall, Paul Butterfield and Ten Years After. We wrote a couple of our own and got pretty good in short order (we were just a blues band, but pretty decent mimics at our young age), booking several gigs around southern Ontario throughout the late spring and early summer of ’69.

One time, about an hour before going onstage at a small club in Ancaster, bright spark that I was, I decided to drop some LSD. Launching into our set, I did my damnedest not to let myself trip—mind over surreal matter. No matter how weird the audience appeared or the band sounded to me at that moment, I had to ignore it, staring with all my might at the fingerboard of my bass and desperately trying to sing the right words in the right order. How we got through the gig I’ll never know, but luckily, it was blues not prog—so ya know, a lot of latitude there—and no one said anything untoward about the show, so I assumed with enormous relief that we had pulled it off. I wonder if Dock Ellis went through the same thing the day he pitched his no-hitter on acid. Maybe he enjoyed the ride, but I certainly did not. All I got out of it was a massive headache and a majorly important lesson: mixing psychedelics and playing, especially in front of people, is a pretty stupid idea.

Quite often I’d run into Alex and John hanging around Ray’s “office”—the apartment he shared with our friend and very first roadie, Ian Grandy. As for Alex and John, despite my being dumped by them, we were still friendly, mostly just hanging around and getting high. I refer to that period as the “Summer of Acid,” as we were so bored and restless between gigs that we’d invariably end up smoking dope or dropping a tab, then raiding Ray’s fridge and eating whatever we found in it. He would come home and start freaking out: “Who ate my salami? Who ate my salami?” while we fell about laughing.

Hadrian was failing to get much work, if any. “I took my new girlfriend, Charlene, to a gig at St. Timothy’s or something,” Alex now tells me, “and I remember how horrible it was. It was so flailing. Nobody could play. Our new singer and second guitar player sat there saying stupid things—reading aloud, I remember, with his glasses and a light on, like, ‘The fool on the hill . . .’ in a self-important voice, and I was like, oh my god, no! What is going on here? After that gig the band just fell apart.”

In the fall of ’69, Rutsey called to ask me back—feeling shame and remorse, apparently. He knew he’d fucked up and that it was now up to him to make amends. “As was so often the case with Rutsey,” Alex says, “after a month or six weeks, he’d suddenly flip. And you’re his best friend all of a sudden!”

The reason I didn’t bear a grudge for long was that I really missed playing with Alex, and still thought that Rush was a more exciting alternative to the band I’d started. I saw the potential for something heavier and more original, and the practical thinker in me was willing to drop resentments. Whatever blow to the ego I may have sustained was behind me, and I won’t deny that there’s something sweet to savour in your ex-bandmates admitting they made a mistake and confessing they need you more than you need them. In the end, the whole painful experience made the sixteen-year-old me more confident, not to mention more skeptical, which, let’s be frank, is not a bad thing to have in your toolkit—especially, as will be amply illustrated later on, when it comes to dealings in the music business.

Meanwhile, Rush was heavying up its sound. And what happened in 1969 to bring this on?

At the corner of Toronto’s Yonge Street and Davenport Road stood a venerable old building most of us had strolled past many times on our way to nearby Yorkville Village without taking much notice. It had been built as a Masonic Temple, but by 1969 that edifice of secrecy had become the coolest rock and roll club and venue in town, the Rock Pile. In February John had been one of the few attendees of a show there by an unknown band called Led Zeppelin. At that time the main draw was their guitarist, the ex-Yardbirds’ Jimmy Page, but Rutsey had been especially blown away by the drummer, John Bonham, whose style and tone were uniquely solid and powerful without ever seeming too busy. He couldn’t stop raving, so as soon as their first album was released we ran to our local Sam the Record Man, only to find that word was spreading fast and it was already out of stock. When the re-order finally came in, we grabbed one, headed home and laid it on my turntable. I can still remember the three of us sitting there on the bed in utter awe, listening to the heaviosity of “Good Times Bad Times,” the fire of “Communication Breakdown” and oh, that drum sound! Plant’s extreme vocal range and Jimmy’s guitar histrionics put this band way over the mark, and for me John Paul Jones’s emotionally moving bass lines welded perfectly to the drum parts, grounding the band and creating a rhythm section for a new age of rock. The Who were full of abandon, rockin’ hard and melodically brilliant; Jimi was musical voodoo and flamboyance incarnate; Cream was a showcase of bluesy virtuosity; but this? This was heavy, man. Zep had reforged the blues in an explosive and very English style that would speak to our generation of players like no other. For us there was Rock before Zep came along, and there was Rock after. This was our new paradigm.

We tried to learn a couple of their songs, but they were beyond us at that stage; even when we got the notes close to right, the sound was wrong. (Zep would only work its way into our set list when Rush was playing the bars, with “Living Loving Maid” from Led Zeppelin II.) Regardless, Zeppelin challenged the way we felt about our own sound: if it wasn’t heavy now, it felt just plain wimpy.

As 1969 wound down, the band went through a period of inactivity— by which I mean zero gigs. We felt ignored by Ray, who was pouring all of Universal Sound’s energies into other, more commercial bands; we were not an “easy sell,” because we insisted on inserting a lot of original material into our sets. I’m not saying we were accomplished songwriters, but we resisted playing songs that had made other bands famous. We reckoned that for us to get anywhere we’d have to write our own.

One weekend, I was at a family gathering talking to my cousin Manny (married to my father’s niece). I liked him; he was only in his thirties, a gentle sort with unkempt curly hair and a bright smile who had always been kind to me, especially after my dad passed away. He was also the only adult I knew who smoked pot, which made him the hippest member of my clan, for sure. He asked me about my band, and when I told him that we felt we were spinning our wheels, he said he knew someone who might help us out. A short while later, he came to one of our practices at Lindy’s house with a friend of his named Vince. They sat on the basement steps listening to us play, nodding their heads—not bothered at all, apparently, by the intense volume. Afterwards, Vince said he liked us and, if we were interested, could be our manager. Now that I think of it, we didn’t even ask him if he had any experience, just stupidly sort of assuming that he did. Well, we were desperate, and I did trust Manny. We decided at a band meeting that we had nothing to lose.

By this time, Lindy had rejoined Rush, but his taste in rock couldn’t compete with our burgeoning desire to be the next Zep. He was more into Procol Harum and some of the bluesier guys; he had a more varied sensibility than we did. He liked folk rock and a lot of things that demanded a four-piece ensemble. In short, it was our first encounter with the time-honoured root cause of countless bands’ breakups: “musical differences.” Shortly after the audition with Manny and Vince, he decided to leave the band for good, and we returned to the trio of John, Alex and me. Meanwhile, when Zeppelin returned for two shows at the Rock Pile that August and I had no money for a ticket, I went down to Church Street and pawned the typewriter my grandmother had bought me for my birthday. I felt super guilty about that, but that typewriter stood no more of a chance than Lindy had.

Vince said we now needed proper publicity material and set up our first real photo shoot—at what we expected to be an actual photo studio but which turned out to be just some guy’s office, all bare walls and empty space. Still, it was as close to a professional situation as we’d ever experienced; before that, we’d simply have friends take snapshots of us outdoors, in parks or anywhere else we thought was a backdrop— and where lights weren’t required.

At the makeshift studio, Vince stood at the back suggesting poses. The photographer had wrapped us in a blanket so that just our heads stuck out (was he thinking of Pink Floyd’s publicity shot from the year before, of the band shrouded in a pink sheet?), and just as he was about to take a shot, Vince said:

“Guys, make stoned eyes. Look like you’re stoned!”

Is this guy for real? I mean, how do you make “stoned” eyes? Then he directed Alex to stretch his hands out in front of his face, eyes peering between his fingers at the camera. Whatever psychedelic effect the guy was after, when we saw the shots a couple of days later, we just laughed at how goofy Alex looked.

He asked us to rendezvous with him at a second-story club on Yonge Street to meet the owner, a guy he knew named Marvin. We were at first excited by the possibility of an actual gig and said okay, but when we walked upstairs we were greeted by signs advertising a strip club called Starvin’ Marvin’s Burlesque Palace. Vince introduced us to this chubby bearded dude, who sized us up and asked us questions about our songs, and it was immediately clear that Vince had been grooming us to be the house band there, playing sets between the strippers.

We said nothing and left the club pretty downcast, indignation rising with every step we took away from the place. Every instinct in my body told me this was wrong. Finally, the guys looked at me and said, “Ged, this is fucked up. No way we’re doing this. You gotta call Manny and get us out.”

Manny was put off at first, but really had no choice. After all, we were cousins. He said he’d take care of it, and that was that. We never spoke of it afterwards, nor did I ever see Vince the hairdresser again, but “Make stoned eyes” lived on forever in the Rush lexicon, never failing to crack Alex and me up, especially in the middle of future photo sessions.

Shortly after that, someone asked if we would be interested in playing a bar mitzvah—but unlike the basement party I’d played at Anthony’s when I was fifteen, this was a big and proper dinner in a rented hall with stage, lighting and all. By then we were playing more high schools and had accumulated a little more gear but were still not gigging a ton and would take (almost) any gig that came along. We set up on the day, and everything seemed to be going just fine . . . until we cranked it up and started to play. The kids were diggin’ it, but within moments the older guests, especially the ladies with their bouffant hairdos and flounced dresses, were running for the exits with their ears covered, yelling, “Make it stop! Make it stop!” The bar mitzvah boy’s father stood in front of the stage waving his hands and shouted, “I’ll pay you, but you can’t play anymore. That’s it, show’s over!” Kinda stunned, we had no choice but to tear our gear down, even as several of those bubbies continued to complain, “Oy, givalt. This you call music?” I can still picture the poor boy watching us pack up and looking forlorn. Sorry, kid. Didn’t mean to wreck your big day.

Meanwhile, I had come to a crossroads with my education. In 1968 I’d started grade ten at Newtonbrook Secondary School, but just a year and a half later was really not into staying the course. The only thing that stopped me from quitting was knowing my mother would be heartbroken.

The looming decision was tearing me apart. All I thought about was music, listening to records and learning songs, working on my chops and trying to write my own material. At that point we were playing high school concerts and dances. Yeah, you heard me right: dances. I know it’s hard to imagine, but we most certainly did play Sadie Hawkins dances, where the girls picked the guys to dance with under a twirling mirrored disco ball, and Halloween dances with everyone in costume. To come clean, people rarely actually danced to our music at these events . . . and we weren’t even playing in 7/8 yet.

One time we were booked to play a high school near Magnetawan, Ontario, about three hundred kilometers from Toronto. We set off at the end of our school day but underestimated the travel time. We got there late, were greeted by the attendees standing out in front of the gymnasium with their arms crossed and had to load in to a chorus of jeering. The audience watched our set from the back of the room. I remember thinking as we played, Weird, don’t they know we don’t bite? Maybe they were intimidated by our volume or maybe they really hated our sound, but either way, though they did eventually warm up a bit, the gig was not a smashing success—and a message to me about priorities.

We didn’t have much gear—two amps, a guitar, a bass and a drum kit. To get to neighbourhood gigs we’d beg one of our parents to make a couple of round trips with instruments poking out of every orifice of the vehicle, but as we were taken farther and farther afield, we started leaning on the few friends we had with licences and access to a car or van. There was Gary “Doc” Cooper, a neighbour of Alex and John’s with a car of his own who’d drive us so long as we paid the gas; Larry “Label” Back was another, and a guy named Ron who had an actual VW van. For several years they helped us hump the equipment, rent a U-Haul or what have you. I can still picture myself crouching for hours atop an amplifier in the back, painfully pretzelled but happy that we were on the road.

However late we’d get back to town, it became a routine of ours to grab a bite at a 24-hour diner called Fran’s, where I’d automatically order the open-faced roast beef sandwich—a very ordinary-sounding memory that conjures up the feeling for me of camaraderie and cheating life just a bit. We ought to have been in school being groomed to become proper citizens but were pursuing our dream instead. Maybe that’s why for Rush’s entire career, having a drink alone with Alex and Neil after almost every show would be so important; it was a nightly reminder that we’d gotten away with it.

Inevitably, as my attendance dwindled and my already mediocre marks took a deeper nosedive, I was called in to see a guidance counsellor, a Mr. Woodhouse, who you could say was my first therapist. He wanted to know it all, my history, my goals and why I was struggling. After a few sessions he asked me if I smoked cigarettes, which I did (back then pretty much every kid I knew smoked). He locked the door and we lit up. It impressed the hell out of me that he was less concerned about breaking school rules than winning my trust. Sometimes we’d drive over to a nearby deli or coffee shop to smoke and talk and drink coffee. He was the first adult male since my father passed away who treated me as an equal. Clearly his primary goal was to keep me in school, but I sensed that he also wanted me to learn to make decisions for myself.

Once he grasped my dilemma, he suggested a compromise: I would be allowed to build a class schedule that would have me done by around one or two p.m. and get me on the road in time for gigs just about anywhere in the province. I chose theatre arts, screen arts and graphic arts, plus English, history and phys. ed. (if they’d had any more subjects that ended in “arts” I would have taken those instead). He pointed out that my post-secondary education options would be almost non-existent if I dropped both math and science, but since I had no intention of going to university anyway, I didn’t care. This schedule, I hoped, would keep me in school long enough for Mom to become resigned to me becoming a full-time musician.

It didn’t work out too well. I was now able to make our gigs on time but was still getting home so late that rising bleary-eyed for an 8:45 class was nigh on impossible, and after a couple of months I was back at the crossroads. Never had Robert Johnson’s words “Believe I’m sinkin’ down” meant so much to me. I knew how much anguish I’d be causing my mother, but I had to leave. Naturally Mr. Woodhouse was disappointed, but he promised to help explain my decision to her, and when he did just that a few days later, sure enough, she broke down in tears. I felt terrible but was undeterred and cleared out my locker. I was now a musician all right, but also a high school dropout, barely eking out a few bucks a week. I was scared but resolute. I had to conjure a proper living now from nothing but a dream and a band (one that had already kicked me out once), if for no other reason than to justify what I was putting my mother through. When I got home, she wouldn’t talk to me. It’s a standard quip to say that Jewish parents want you to become a doctor or a lawyer, but she really thought I was insane. The music and the culture were utterly alien to her. She figured it was a one-way road to drug addiction, at best the equivalent of running away to join the circus.

Thinking back on that critical juncture in my life, I’m struck by what a different person I’d become from the one I’d been as a little kid. For years I’d been chronically indecisive, a procrastinator, vague and aimless, possessed of few opinions. Neither parents nor teachers had ever really encouraged me to make up my own mind about anything. I was sheltered. I was a blank page. Mom and Dad simply told me to do what I was told, and I obeyed. The only helpful thing my mother ever said to me in that regard was after she’d been watching me play with a bunch of kids on my street and saw that anything they did, I did. That’s when she pulled me aside and said, “Garshon. Be a leader, not a follower.” Even though she’d never taught me in my early life how to be a leader—on the contrary, in fact—she apparently expected me to be one. I have to imagine that her memories of the war—with an entire race of people following one another into the gas chambers—had taught her this in the hardest of all possible ways.

That phrase in her voice would reverberate in my brain throughout my life. As I grew, I made conscious efforts to formulate opinions, to educate myself so that I could participate in conversation and examine my own feelings about any given subject. I expended a lot of internal energy trying to grow myself in such a way that allowed me to actually have interests; to absorb things; to react to things and then analyse those reactions—in the end, to form opinions, which after all is what makes a person a personality. And one result of developing a personality was that I became more decisive. Still, it’s funny: she gave me the right advice, but as I did start to become a leader, not a follower, and my decisions went against her ethos—leaving school, joining a band— really it was “Be a leader, don’t be a follower—so long as you agree with me”! After I quit school, between us it was—for want of a better term—cold war.

But boy, was Mr. Woodhouse ever what one could hope for in a counsellor. After all the success I’d later enjoy, I sometimes wondered if he was aware of just how profound an influence he’d had on my life. More than once I’ve thought of looking him up but got cold feet. Is it ever too late to say thank you?

From the book My Effin’ Life by Geddy Lee. Copyright 2023 by Geddy Lee. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Best of Rolling Stone