The Gamble of Francis Ford Coppola’s Career (Exclusive Excerpt)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

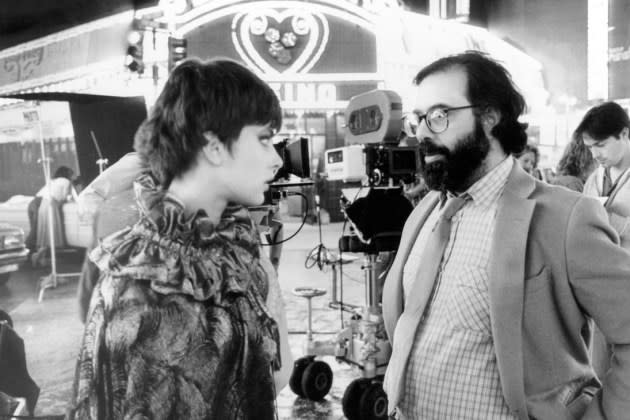

Francis Ford Coppola has been thinking about utopia his whole career. His upcoming, self-financed epic Megalopolis is about just that. But his first experiment with utopia climaxed in 1980 with the creation of Zoetrope Studios, which he imagined would be its own top-to-bottom, all-encompassing, soul-enriching creative ecosystem free of Hollywood dysfunction. Its initial project was to be the hugely ambitious musical romantic drama One From the Heart, starring Teri Garr, Frederic Forrest and Raul Julia. The 1981 film may have bombed at the box office, but the story of its creation is far brighter, revealing how Coppola’s cast and crew came to believe in his grand vision, and helped him overcome financial disaster. As a new director’s cut of the film comes to New York’s IFC Center on Jan. 19 and L.A.’s Cinemathèque on Jan. 26, the following excerpt from Sam Wasson’s new book The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story describes the gamble of the director’s life, and the show of genuine solidarity — unheard of in Hollywood before or since — that brought him to tears: “Hell, yes, I’d work for him for nothing, and so will a lot of the rest of us.”

Below, The Hollywood Reporter shares an excerpt.

***

In 1980, fresh off the hard-earned success of Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola bought the Hollywood lot formerly occupied by General Service Studios and established Zoetrope Studios, which he hoped would revolutionize how films were made. Coppola had grand dreams: he would build at least six parks around Zoetrope. He would develop a training program for underrepresented Zoetrope employees of the future. He would rent out space with no overhead charge to producers. He would offer two acting tracks, one for contracted actors in his repertory company, the other for freelance talent. He would do the same for writers and directors. Instead of giving out percentage points in individual films, he would give his contract players a share in the profits of the entire studio. Should they want to work elsewhere while under contract, he would, within reason, encourage them. For Zoetrope workers and their families, he would enlist Hollywood professionals to lead free studio workshops in the art of filmmaking. He would open a Zoetrope Studios restaurant, several restaurants, so employees and their families would eat—and for free. He would open a library. He would screen, night and day, favorite films. He would sign directors emeritus to serve as artists in residence. While at Zoetrope Studios, they would develop their own dream projects and act as ubiquitous mentors to Zoetrope artists. He would open the lot to the greater community, like a museum or public park, and host film festivals, dance festivals, and drive-ins. He would lease the Pilot Light Theatre, on nearby Santa Monica Boulevard, for Zoetrope rehearsals and auditions by day and ticketed performances by night. He would expand to New York and develop a Zoetrope theater division. He would oversee fifteen modestly budgeted films a year. His name and reputation would earn him a healthy line of credit from Chase Manhattan; European and domestic distributors would provide the rest. He would devote a staggering 50 percent of Zoetrope’s profits to research and development. He would have parties. He would keep his bungalow door open, even while he worked. He would nurture a creative ecosystem that would keep everyone happily employed forever. No one would have to go to the jungle again.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Zoetrope’s first major project, its proof of concept, was One from the Heart. MGM had brought him the script, by Armyan Bernstein. It was a love story. Hank and Frannie, regular folks, reach a dull patch in their relationship. They split, find the lovers of their dreams — or so it seems — and in the end, reunite. Fantasy is only a fling, the story says; the real thing is forever. Coppola wanted to turn it into an epic musical, complete with full-size recreations of several Las Vegas streets.

As One from the Heart approached its first day of filming the little love story that became, first, a $15 million musical had now increased in size and spectacle to the tune of nine soundstages, not the intended two, and at a cost of $23 million.

For Coppola, who had bet big and scored big on Apocalypse Now, the additional millions were the cost of doing artistic business. With the new budget backed by Chase Manhattan and certain foreign presales, he could safely say his investors agreed. But in December 1980, only weeks before cameras were set to roll on One from the Heart, Coppola was notified that $8 million of that the film’s foreign investment had been unexpectedly withdrawn. Instantly, panic set in.

Eight million dollars—gone.

There was no recourse. “If that occurred in a [Twentieth] Century–Fox or Paramount, they would reallocate eight million from someplace else and solve the problem,” Zoetrope’s then president Bob Spiotta explained. But Zoetrope, being a private corporation, 100 percent owned by Francis Coppola, there was no “someplace else.” The timing simply could not have been worse; had the eight million dollars been withdrawn earlier, before set construction began, Coppola would have sought new financing or reconsidered the late-in-the-day addition to his studio’s multimillion-dollar replica of the Las Vegas Strip and its surroundings. At such a late stage, however, Coppola couldn’t pause the film to raise additional funds; he had cast and crew schedules to account for. Nor was MGM, who had paid Coppola his $3 million directing fee in exchange for a piece of One from the Heart’s gross, willing to swoop in to lend a hand.

Coppola had no more distribution rights to offer any new financier. Instead, he offered to exchange a piece of his gross percentage for money up front, but at its $23 million price tag, One from the Heart’s break-even point was already too high, it seemed, to make further investments worthwhile. Zeotrope’s head of production Lucy Fisher put it simply: “We had too many bed partners.”

Coppola had, then, two choices: he could either fold up his tent or, seriously in debt, figure out a way to proceed, as planned, with One from the Heart, which now represented—more than Apocalypse, far more than any love affair—the gamble of his life.

He chose to proceed.

“Anyone in this business with any kind of experience has got to evaluate that as being at least reckless,” Spiotta said, “because we didn’t have the funding to last one week.” Zoetrope did have nonliquid assets of $55 million, but they were tied up in studio real estate and equipment. How could he sell off his studio as he went into production at his studio? They couldn’t shoot the film without sets and cameras.

Coppola shifted into action. He put up $1 million of his real estate holdings in San Francisco as collateral against a loan from Security Pacific Bank set at 21 percent interest — high. And he knew it would not end there. “To get through each week of shooting,” he told the press, “I will have to put up $1 million week by week from the real-estate package that represents all my personal assets, until I’ve put up the $8 million.”

February 2, 1981— the first day of production. “We had so much light,” Gray Frederickson said (by one estimate, $300,000 worth of neon alone), “that, when we turned it on for the first day of shooting, it browned out Hollywood.”

When at last they made the first shot, Coppola gave the signal, and champagne was passed around for all. Coppola held up his glass. “We’ve begun!” He then disappeared back to where he had come from: his Image and Sound Control vehicle.

The next day, he was forced to lay off Zoetrope’s entire story department. “Basically,” Lucy Fisher told the press, “we are changing our orientation from that of a financing organization to a production entity that will concentrate on the pictures we already have in development, so we may not be able to support a large staff of story editors and readers.” They would now hire development personnel on a picture-by-picture basis.

But without an influx of capital immediately, it would not be possible, Coppola realized, to proceed with One from the Heart.

Days after the press conference, Zoetrope couldn’t make payroll. Vulture-like, Paramount landed on Coppola’s shoulder, sniffing the air around his assets. They were interested in the script for Interface, a sci-fi feature script that experimental filmmaker Scott Bartlett was to direct for Zoetrope Studios. Paramount made an offer of $500,000 and threw in another $500,000 loan to Coppola, an advance against One from the Heart. But Coppola did not want a partner, let alone a corporate influence such as Paramount, in a project as transgressive as Interface. But of all the scripts in his bank, none was further along. The picture could even begin shooting at Zoetrope Studios (renting facilities to Paramount) in two months’ time. “Francis shouldn’t be shut down,” Paramount’s Barry Diller proclaimed with dubious magnanimity. “He is a national resource.”

A national resource without resources, Coppola accepted Diller’s offer. It bought Zoetrope two weeks of paychecks — one for the week outstanding, the other for the week upon them, February 10, 1981. What would they do then?

They had been shooting One from the Heart for only one week.

Following a period of extensive deliberation, the decision was made to have Spiotta deliver the message —that living from hand to mouth, they would invariably run out of money again (and again . . . ) — to the cast and crew and all remaining Zoetrope Studios personnel, “because,” Spiotta explained, “Francis being the emotional guy and dedicated guy, and sometimes impetuous, might get involved in saying, ‘Hey, I guarantee all of you people and your children’s education and everything,’ and that would have been a disaster.” Spiotta would do it in three meetings.

He would be direct. “I simply told them what the situation was,” Spiotta said. Sweating, he faced the 155 Zoetrope Studios staff people who had gathered in the screening room. “Imagine a lifeboat,” Spiotta explained to them, “and it’s full of people, and there’s x amount of bread. We’re going to go on half rations.” Some would be laid off, he said, beginning with those not essential to the production of One from the Heart. “Rather than lay off a great number of people and shut this down and make this production impossible, our attitude was we would try and trim as few people as possible.” Worst-case scenario, they’d work for two weeks at half pay. That’s what he was asking. Would they be willing?

To Spiotta’s astonishment, they would be. Francis had bet so much; why shouldn’t they? “The mood here is one of hope,” said one Zoetrope worker after the meeting. “We’re all behind him. We all support him. People with all their hearts want it to go. The studio is a baby, and it’s going to take nurturing and care before it’s going to blossom.”

One meeting, two to go.

Spiotta faced the Zoetrope Studios construction staff: tough guys, mostly. They had come to “Fremont Street,” Stage 9, to hear the bad news. Just how many there were — several hundred, Spiotta guessed — was a terrible surprise to him, and “all of them had mortgages to pay and car payments and whatever else people do with their money.” As briefly as he could, Spiotta tried to explain how Zoetrope had gotten into this situation. He said that while it might look like Francis was being irresponsible, he was doing what he had been doing all along, what he believed was best for all of them, as artist and businessman, the 100 percent owner of the company and studio. “The bad news,” he proceeded, trying to hide his embarrassment, “is that a comprehensive package resolving this has not been put together. It’s still alive, but it has not been put together. The good news — good for us and bad for Francis — is that Francis went out and, by hook or by crook, bummed some more bucks . . . Essentially, Francis borrowed more money. Enough to cover the payroll for last week . . .”

They — all these union guys — listened quietly. That in itself was a shock to Spiotta. He had expected a vengeful scene out of On the Waterfront. And then, “almost in unison,” Spiotta recalled, “they responded in an incredibly supportive way.” He wasn’t sure if they were being sarcastic. But then they started asking questions. Some, Spiotta said, were even “saying kind of corny, non-jaded things that you don’t expect to be said in this town” . . .

“Can we help?” was one question.

“Maybe we can chip in,” said someone else. “Can we invest?”

“How about everybody putting in a hundred bucks?” “We’ll work anyway.”

There was applause, a round of applause . . . it grew . . . “We’ll keep working . . .”

Spiotta was amazed. This isn’t Waterfront, he thought; it’s The Pajama Game.

Looking around the room, he began to cry. All these faces, suddenly all in agreement. “What they simply said is that they would be patient,” he explained, “and ‘Get us the dough as quickly as you can.’ And then, just as the meeting ended, somebody came in and said the union called and they are willing to support whatever the people want to do, and the support is 100%.” Some approached Spiotta after the meeting, hats in hand: “We really appreciate what Zoetrope and Francis are trying to do. We’re proud of it and we want to help you.” Said Al Price, business agent for Local 44, “If a man’s a friend and he gets in trouble, you don’t kick him when he’s down. Mr. Coppola came to this town. He bought a dilapidated studio, rebuilt it, and extended a hand of friendship. As a goodwill gesture on our part, I asked our members to stay on the job, and I think it was the proper thing to do.” Construction foreman Al Roundy said, “Coppola has treated us right, like human beings. The union gives us a 30-minute lunch break. Coppola gives us 45 minutes. Hell, yes, I’d work for him for nothing, and so will a lot of the rest of us. He’s a hell of an improvement over any of the other studios.”

It was a Thursday. Union officials permitted members to continue working on One from the Heart with the understanding that the production’s cash problems would be resolved over the weekend, by Monday. “Francis was literally in tears when I told him about it,” Spiotta said.

Dan Attias was the one to knock on Coppola’s bungalow door before the third and final meeting, this one for the cast and crew of One from the Heart.

“Are they ready?”

“Yeah.”

Inside projection room one, Coppola stood by quietly—few, if any, had seen him silent before—as Spiotta carefully reiterated, one last time, what most already knew: Zoetrope had come up short both on its $600,000 payroll and on the $600,000 due to outside vendors. Unions were prepared to grant them a waiver through Monday; until then, he and Coppola would be meeting with bankers and financiers around the clock . . . But then, wrote the Herald-Examiner, reporting on the scene, “something that has never happened before in the history of Hollywood movie-making occurred”: instead of walking off the job, all present agreed to forgo salaries and stay on until Coppola got the money. “I’ve never seen anything like what happened,” Frederic Forrest said. “As in a scene from a Frank Capra film,” film critic Todd McCarthy wrote, “over 500 employees at Zoetrope Studios yesterday afternoon voted unanimously to continue working without pay after being told that management would not be able to meet this week’s payroll.” The decision, wrote Dale Pollock in the Los Angeles Times, “is virtually unprecedented in Hollywood labor annals.” “This type of loyalty has no price,” echoed Gerald Smith, business representative for the cameraman’s local. “It hasn’t existed in this town for years.” Zoetrope publicist Max Bercutt went further still: “Never in forty years in the business have I known employees to come to bat like this for a troubled producer. This is a first.” When at last it came time for Coppola to speak, he managed only a few words. His voice cracked. He looked at the floor. McCarthy reported, “Coppola was unable to restrain his emotions, crying openly in the wake of an action unprecedented in the memory of industry vets.” Bernie Gersten would write, “What was interesting was that all of us seemed to share — at least at that moment — a common belief in the work we were engaged in and the conviction that somehow the film and the company would pull through.” The crowd broke into hugs and cheers, and Teri Garr said, “Time isn’t money anymore. Time is just time.” Kenny Ortega would speak for most: “For those of us that were, like, really month to month, like myself, it was, like, I don’t care. I’ll sleep in my car rather than not be where I am today.” Carpenters, painters, electricians, dancers, stars, executives — they, not just Coppola, were all gambling together now.

From the book THE PATH TO PARADISE: A Francis Ford Coppola Story by Sam Wasson Copyright © 2023 by Sam Wasson. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter