#FreeCyntoiaBrown: New memoir chronicles prison, Rihanna, marriage and future plans

Cyntoia Brown-Long was on her way to her job as a teacher’s aide in a classroom at the Tennessee Prison for Women when a guard yelled her name. People were tweeting about her, he said.

She didn’t believe him. But a few hours later, in a phone call with the man she would eventually marry, she was read a tweet from Rihanna.

The pop icon had posted a picture of Brown-Long in pigtails at age 16 — when she received a life sentence for the murder of a 43-year-old Nashville man — with the hashtag #FreeCyntoiaBrown.

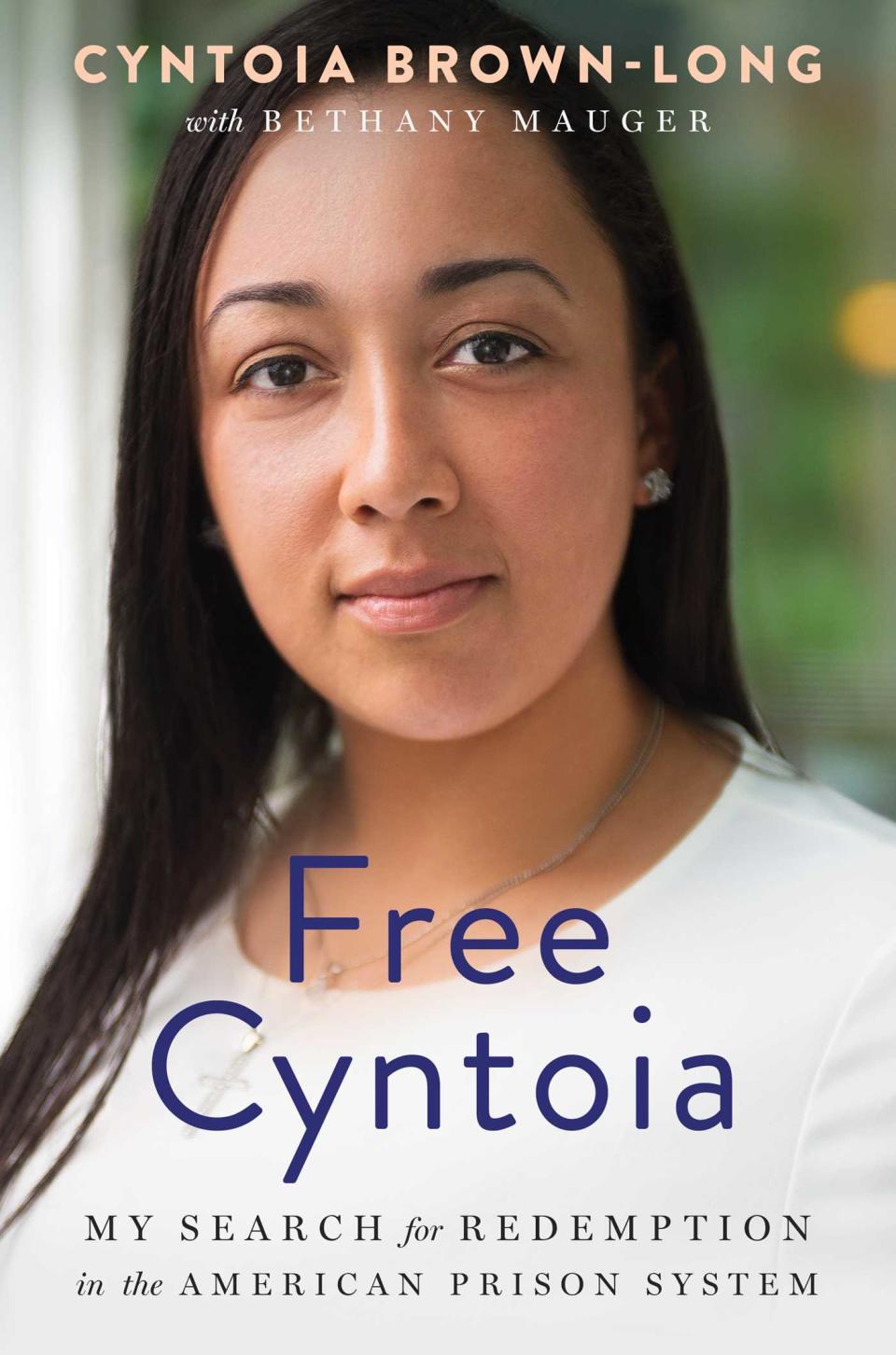

“I took a deep breath and closed my eyes,” Brown-Long writes in her new memoir, “Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System” released Tuesday.

“How many likes does it have?” she asked.

The response — “two million” — left her in shock, her legs buckling under her as she fell back onto a chair.

Less than two years later, Brown-Long was free. Former Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam took the rare step of granting Brown-Long clemency, commuting a mandatory 51 years behind bars to 15 years served. Brown was released August 7.

Cyntoia Brown's path to freedom

The memoir, begun while she was incarcerated, chronicles the 31-year-old Brown-Long’s life from her childhood to the initial days after her release from prison. On her first night of freedom, she opened a can of ravioli and took a bath by candlelight in the brick two-story Nashville home her husband had bought for her.

Brown-Long, who has pledged to be a voice for women and girls who are victims of sex trafficking, dedicated her memoir to “all the women, men and especially juveniles serving time in the American prison system."

Her early years in prison were marked by fits of unruly behavior, fighting other inmates and talking back to guards. She was sent to segregation units and, later, transferred to a Memphis prison as punishment.

When she returned to the Nashville prison, Brown-Long was more serious. She pursued an associates degree in a Lipscomb University program in Nashville that brought enrolled students inside prisons to study alongside prisoners.

Brown-Long credits the teachers and students who "smelled like Pantene and Calvin Klein Eternity" with broadening her perspective and helping her focus on what she could accomplish.

“What if I could really do something?” she wrote. “What if I could get out of this prison and help people somehow? For the first time in years, I pictured what my life could be like beyond the prison walls. I pictured myself as an advocate somewhere, helping young girls fro making stupid mistakes and winding up where I did. If these Lipscomb kids listened to me, maybe other kids would too.”

A Lipscomb professor, Preston Shipp, introduced the idea of restorative justice. It's the notion one can repair damage and reconcile the person who had done wrong to the person who was wronged.

The idea was at odds with her experience with the criminal justice system, she wrote.

“I thought back to the courtroom, seeing the mother of the man I’d killed sitting across the aisle. I wanted more than anything to tell her I was sorry for what I’d done, but my attorney, Kathy (Sinback) wasn’t having it.”

“You can’t do that,” she said. “It would tank your case.”

“I realized how truly messed up the system was," Brown-Long wrote. "Don’t we want people to feel remorse, to swallow their pride and reach out to the person they hurt? There’s no room in the criminal justice system, not the way it’s set up today. I never got to apologize to my victim’s mother. She would die before I had the chance.”

5 books not to miss: Ronan Farrow's 'Catch and Kill,' Elton John memoir, Ali Wong hilarity

Brown reflects on Johnny Allen, 'Kuttthroat' and trafficking

Brown devotes two sentences in the 301-page book to the crime that landed her in prison. In 2004, she admitted to shooting Johnny Allen, 43, as he lay in bed next to her. In court testimony, Brown said Allen had picked her up for sex and she shot him, fearing he was reaching for his own weapon.

In prison, Brown reflected on what led to that moment - the casual, demeaning and often abusive ways that adult men treated her, including the 24-year-old boyfriend nicknamed "Kutthroat" whom she said forced her to walk the streets of east Nashville looking for men who would pay her for sex - and beat her when she didn’t earn enough.

It was only later that Brown heard the term “trafficking” applied to her. It wasn’t a term she associated with her own experience. But she plunged into research, reading studies on human trafficking and brushed up on federal law that defined trafficking as involving anyone under 18 engaged in commercial sex.

Brown had started at age 15.

“My body froze as I read the words,” she wrote. “Huh, I thought. That kind of sounds like me.”

“My heart pounded as my body coursed with anger,” she wrote. “I felt a righteous anger for the girls still out there, the girls no one pays attention to...We’ve got to do something, I thought. If this problem was ever going to change, people need to be educated. And I was fixing to do it.”

More: Ronan Farrow talks about his explosive new book 'Catch and Kill'

As part of her final project for Lipscomb, she created the Glitter project. Glitter, or Grassroots Learning Initiative on Teen Trafficking, Exploitation and Rape, would draw attention to human trafficking in the way the ALS ice bucket challenge went viral on social media to draw attention to the disease. Instead of people posting videos of soaking themselves in ice water, maybe people could throw glitter bombs or paint their bodies with glitter to highlight human trafficking, she wrote. She hoped it would go viral.

Instead, Long-Brown herself went viral, with celebrities including LeBron James, Snoop Dog, Kim Kardashian highlighting her case.

Separately, a team of volunteer attorneys were appealing her case while preparing a clemency application for Haslam.

In January, Brown-Long got the news from her attorney, Charles Bone. “You go home in August,” he said.

By then, she already had plans to marry. Jaime Long had first written to her two years before, after reading a story about her. The two corresponded and talked on the phone. Long helped guide her to a deeper faith in God, she wrote. He visited her in jail twice. He bought a diamond ring and asked Long-Brown’s mother for permission to marry once Long-Brown was freed from jail.

Long-Brown didn’t want to wait, she wrote.

“If marriage was on the table, I wanted it now. For most of my life, I’d lived under someone else’s rules, under someone else’s control. This was one thing I wanted on my own terms.”

On January 28, the pair married by phone under a law allowing inmates to get married by an in-person proxy.

In an epilogue, Brown-Long describes her final moments in prison. At 1:15 a.m. on August 7, a guard shook her awake saying “it’s time to go.”

Prison officials drove her to the now-shuttered Tennessee State Prison, a detour that kept her away from waiting media outside the women's prison. There, she slipped into the back of a van next to her husband.

In her new home, with Bible verses on the walls that held special meaning to her and her husband, “I truly understood what freedom meant," she wrote.

“Until this point, I’ve been captive to so many unfulfilling roles,” she wrote. “Outcast Cyntoia, delinquent Cyntoia, convict Cyntoia, heathen Cyntoia. Now I am exactly who and what the Lord called me to be: free Cyntoia.”

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Cyntoia Brown: New memoir chronicles prison, faith and future plans