How Former Academy Executive Director Bruce Davis Solved the Mystery of Oscar’s Name

This story about Bruce Davis and his book, The Academy and the Award, originally appeared in the Race Begins issue of TheWrap magazine.

When Bruce Davis retired in 2011 after 20 years as executive director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, he had an idea for how he might spend the first couple of years of his retirement: researching and writing a book about the history ofthe Academy and its award. After all, he knew the organization inside and out and he could get access to the voluminous internal files that were held in the AMPAS archives. “I told a lot of people, ‘I think it’ll take six months of research and maybe a year to write it,’” he said, laughing. “It was an exercise in naivete all the way along.”It took closer to a decade, but Davis’ book, The Academy and the Award, was published by Brandeis University Press this October. When the book came out, he sat down to talk to TheWrap in the Hollywood home where he used to park his Prius with the license plate AMPAS. (When he retired, so did the plate.) Here, Davis singles out a few of the things he learned.

Bette Davis, Sidney Skolsky and Margaret Herrick did not givethe Academy Award the nickname “Oscar.”

“I was determined to try to solve the mystery of Oscar’s name,” said Davis, well aware that the arguments over who first cameup with the term had been raging for most of the last century. Over the years, the three loudest claimants were actress Bette Davis, who won an Academy Award in 1936 and said she decided his posterior reminded her of her husband, Harmon Oscar Nelson; Academy staffer Margaret Herrick, who said the figure reminded her of her Uncle Oscar; and gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky, who claimed he borrowed the name from vaudeville comics when he was filing a story in the wee hours and had trouble spelling statuette.

The problem was, it was easier to prove who didn’t coin the name than who did. Bette Davis’ eureka moment gazing at the backside of her Oscar came two years after the name had already been used in print; Herrick didn’t have an uncle named Oscar, and nobody has ever found the newspaper article in which she said a reporter conveniently hanging around the Academy office wrote about her new nickname for the award; and the first time Skolsky used the name in print, he pointed out, “To the profession these statues are called ‘Oscars,’” a sentence he would not have written if he was inventing the nickname on the spot.

“I think I pretty well shot down the three major claims,” Davis said. “So it could have been somebody else that nobody ever heard of — but oddly enough, we also have an account of Eleanore Lilleberg.” An assistant in the early days of the Academy, Lilleberg was in charge of the statuettes from the time they left the factory until the ceremony. Davis found a manuscript by Lilleberg’s brother that said his sister beganreferring to the statuette as Oscar after a Norwegian army veteran in theirChicago neighborhood who was well known for standing ramrod straight. He also found two other Academy sources from the era who told similar stories crediting Lilleberg in separate interviews. Davis eventually decided that Lilleberg was the likeliest source of the name — and then concluded his chapter on the naming with this fact: “Almost unbelievably, the word ‘Oscar’ was not registered as a copyright until 1975.”

Also Read:

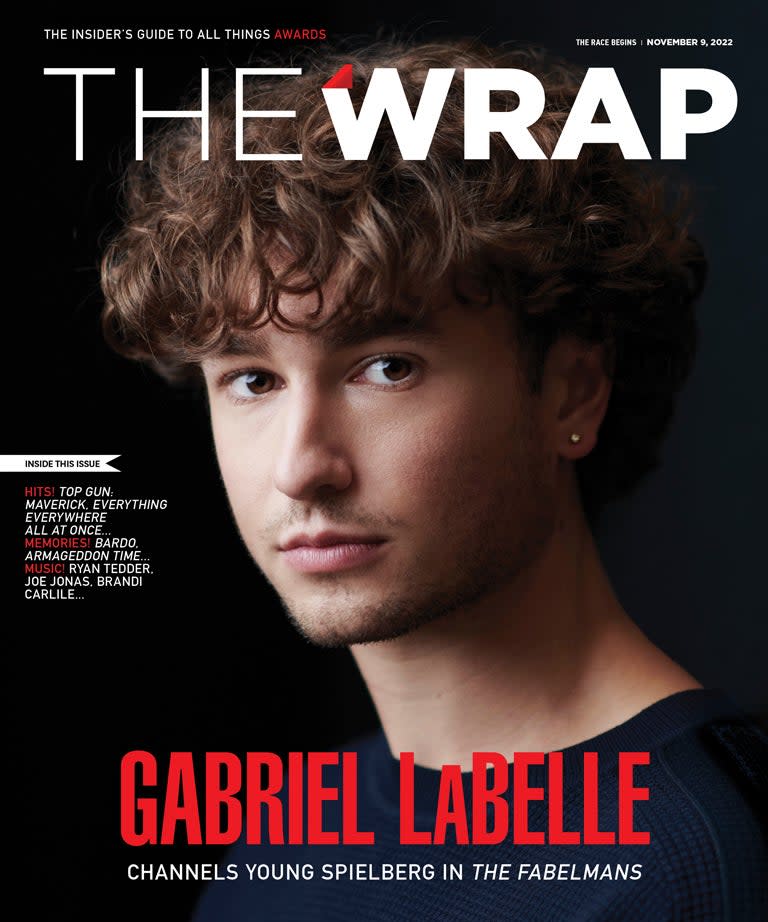

‘The Fabelmans’ Star Gabriel LaBelle on Playing Steven Spielberg and Being ‘Spoiled’

Bette Davis did not leave the Academy presidency after big fights with the Board of Governors.

Every time a woman is elected president of the Academy—this year, for instance, when Janet Yang landed the job — the time-honored tale is trotted out of how the Academy’s first female president, actress Bette Davis, clashed with the AMPAS Board of Governorsand quit the job abruptly. “I bought the idea of Bette Davis having huge fights with the board, and I started looking back through stuff,” said Bruce Davis (no relation to Bette), who had access to the complete minutes of every board meeting. “First of all, it was fascinating to realize that her presidency only lasted 50 days and was basically interrupted by Pearl Harbor.”

Davis was elected on Nov. 6, 1941 for a term beginning with a board meeting on Dec. 4. The minutes of that meeting show that Davis lobbied for a change in the rule that allowed extras to vote for the Oscars, and that the consensus in the room was, “It is preferable thatthe Academy Awards be conferred by vote of the Academy membership.” She also recommended that studios end shooting at 5 p.m. on the day of the Oscars, a proposal that was quickly adopted.

In a book she wrote in 1962, though, Davis insisted that the meeting was stormy and her ideas met with resistance. That was the only board meeting she attended; she was out of town when a Dec. 17 meeting was held to discuss what should be done about the Oscars in the wake of America’s entry into the war, although she sent a letter endorsing a plan (a ceremony but no banquet) that was adopted. And then she resigned on Dec. 20, in a letter that simply said she thought she would be more valuable working with other organizations more closely involved in the war effort.

“It’s almost like she got angrier about her treatment as the years went by,” Davis said. “At the time, it seems to have been pretty cordial. She quit because she thought there were more important things to do during a war than worry about movie awards. So God bless her.”

Also Read:

Oscars International Race Hits 92 Entries, One Short of All-Time Record

It may have plenty of money now, but the Academy was very broke for a very long time.

Even though Davis had an inside view of AMPAS finances during the decades he spent as executive director, he had no idea just how shaky the Academy was for its first 50 years. “The biggest surprise, hands down, was the financial history of the organization,” he said. “They were scraping year after year trying to get by, and there’s literally a year when they have to take up a collection to make Oscars. The only source of income was dues, and the Depression hit right after it was formed.”

It didn’t help, he added, that the Academy founders had no idea that their awards show could become a source of almost all the income they’d ever need. “Even when they started allowing the show to go on the radio, nobody says, ‘Hey, we could get some money for this.’ Andso they start this pattern of having to appeal to the producers organization over and over again. And as the guilds begin to emerge, the people in the guilds are so suspicious of the Academy because it has producers as significant members. And this huge hostility builds up.”

He shook his head. “I don’t think most people know what a hardscrabble existence the Academy led until well into the television era, actually.”

Read more from the Race Begins issue here.