First person: Memories, and generational truths, uncovered in work to clear parents' home

“Mom, why do you have a tree branch in your kitchen drawer?”

“You never know when you’re going to need a good tree branch,” she said. Made perfect sense — to her. She and Dad grew up during the Great Depression — and hard lessons are never forgotten.

That was about a dozen years ago. She and Dad are both gone now.

With the return of the holidays, memories come flooding back. Memories of Mom. Memories of Dad. Memories of gifts given and received — and sometimes memories of memories that roared back to life as I sorted through all the stuff they left behind.

More from Janet: First person: How I moved from grief and guilt to holiday healing

After each passing, the job of distinguishing trash from treasure fell to me. Another rite of passage, I guess. As a teacher and occasional writer, I’ve contemplated the lessons to be learned — about the histories, the boundaries, the mystery of who collects those bags set at the curb.

Lessons for those of us who are still here, amassing our own piles of stuff.

Lifetime habits developed by lean early years

But to understand those lessons, we must start at the beginning.

Born in Cuba in 1930, Mom and her family had no running water or electricity, and their kitchen floor consisted of dirt. They raised cows, donkeys, horses, sheep, chickens, turkeys, lambs, and pigs. Grew corn and beans, made their own butter and cheese, fished, and managed beehives.

Born in Indiana in 1929, Dad and his family raised goats, chickens, and rabbits. His dad, a minister, was sometimes paid with a bushel of corn or potatoes.

The depression eventually faded into their rearview mirrors, but decades later it was still in their DNA.

Even though by the 1970s we were living comfortably on Dad’s income as a West Palm Beach optometrist, Mom kept everything that might one day come in handy:

Wrappers from our daily Palm Beach Post, twist ties from loaves of bread, rubber bands from broccoli bunches. Used Ziploc bags, tin foil, cooking oil, wrapping paper, gift bags, shopping bags, and boxes. Jars, containers, scraps of fabric, every vase ever given to her, the elastic from Dad’s worn-out underwear, even the cloth from his underwear — to be deployed as dust rags.

For his part, Dad wouldn’t part with newspaper clippings, books, magazines, or VHS tapes. Hundreds stuffed his drawers and shelves.

As a teenager, I didn’t understand their Depression-era mentality. In fact, it annoyed me — so much so that whenever they went out of town, I filled a heavy-duty trash bag with whatever I considered to be garbage. I figured I was doing them a favor: If they couldn’t bring themselves to part with anything, I would help them by spiriting it away in their absence.

But my crime was always discovered. I apologized.

Lesson: I needed to respect their property and choices and work on squashing my impulse to declutter. (Confession: I continued to make old and expired food disappear.)

After my brothers and I moved out, Mom and Dad’s capacity to hold on to things expanded. They filled every empty closet, drawer, shelf, corner — every nook and cranny.

When Mom, a former hairdresser, became a grandmother, she even saved the hair from the haircuts she gave her grandchildren.

One Christmas, my then 20-year-old nephew Zach received a wrapped Ziploc bag filled with his curly hair — and a pair of shorts with a yellow Ty Beanie Baby duck sewed onto the rear end: Mom was finding uses for the stuffed toys that had reneged on their promise to pay for my brothers’ and my college education.

(Every family needs a jokester. Zach is ours. We still laugh about his most memorable presents.)

Decluttering is also opportunity to share memories

The few times Mom relented and let me help her declutter, I wanted her to make snap decisions. She wanted to reminisce. No wonder she started declining my help.

“I’m not dead yet,” she said. “When I die, you can have a big garage sale.”

Lesson: I wish I wouldn’t have seen her things as just things and would’ve listened more carefully to her stories — to the nostalgia (people, thoughts, emotions, time periods) associated with her memorabilia.

My patience and compassion for my parents did increase; especially as their bodies wore out, they became more and more dependent on me, and all six of their siblings and numerous friends died. But also as I matured and experienced losses of my own.

I came to understand why my parents’ home and possessions comforted them, even though that comfort sometimes came at a price.

When they put $10,000 down on an assisted living place in Delray, Mom seemed at peace with a bit of downsizing and offered up the contents of her four china cabinets — yes, four — to family.

But when moving day came, Dad had a panic attack. So, they stayed — even though doing so meant they lost their deposit. The door to culling their possession-filled home also slammed shut.

When Mom died in March 2020, my 90-year-old Dad wanted to stay in the Lake Clarke Shores home they had bought in 1967 (for $20,500!). He needed attention, so a caregiver stayed with him weekdays. I got to be with him on weekends.

As long as his caregiver and I gave him the sports section of the newspaper, fed him (especially ice cream), and put his favorite shows on TV, the happy tunes he whistled during commercials let me know he was content.

If Dad had died first, Mom wouldn’t have let me help her clean out, but Dad didn’t care.

So, while he watched "Andy Griffith," "Lawrence Welk," "I Dream of Jeannie," "Bewitched," or football, I began to sort through the rooms, closets and crannies. Whenever I walked by with a big trash bag, he’d ask, “What’s in that one?”

“Garbage. Want to look through it?”

“Oh, no, no, no.”

Out it went. I put piles and piles by the road. Sometimes, the bags disappeared overnight. Whoever took them must have been disappointed, but I wouldn’t be my parents’ daughter if I had thrown away anything of much value or use.

Getting rid of years' worth of 'stuff'

I spent days shredding ancient paperwork — FPL bills from 1968 and tire receipts from 1971. I recycled endless heaps of cardboard, paper, plastic, and glass.

I became the family archivist, lifting pictures from photo albums and scanning them for my children, brothers, nieces, nephew, and cousins.

A testament to the hoarding a mother will engage in: Mom saved our baby teeth. (Yes, I kept mine, and, yes, I have my children’s, too.)

Pawing through my parents’ possessions felt intrusive, but I loved seeing what they cared about and reading what they had written or read: from the inscriptions in their yearbooks to the love poem Dad wrote Mom when they were dating. Stories and five books Dad wrote by hand or typed on a typewriter. Cards and letters, including mine from college, when long-distance phone calls weren’t in my budget.

These forgotten treasures took Dad back to happier times. In one of the last cards to Mom, he wrote, “To Anna, my lovely wife of 62 years, you have always been my dream girl. I have always cherished you and always will. Thank you for putting up with me. Love, your loving husband, Spencer.”

I’m hoping that made up for the time he gave her a “recycled” card: “Happy birthday to a great guy.”

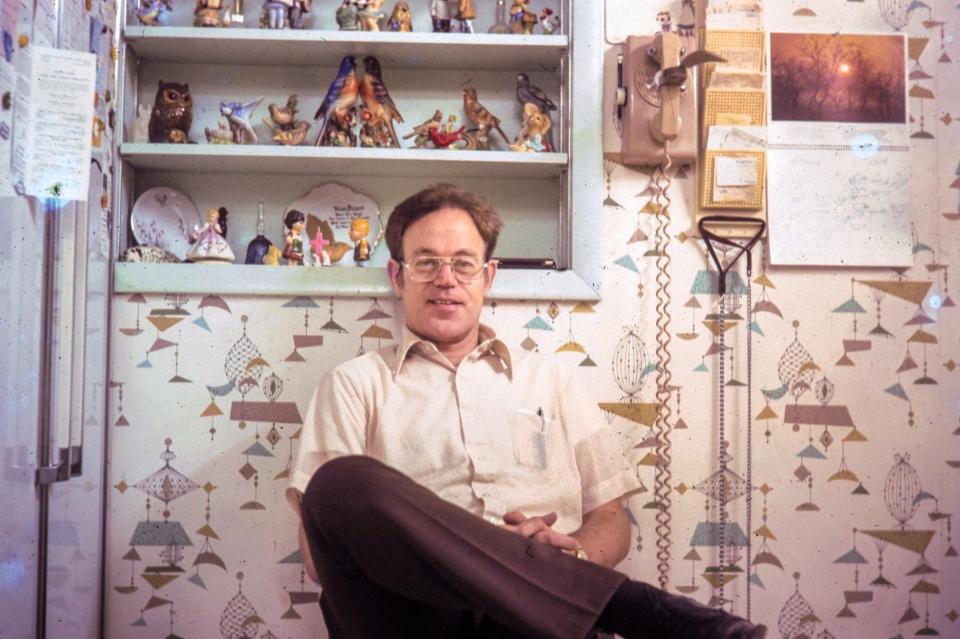

My excavation turned up a thousand or so 35mm slides. Using one of three projectors I found, Dad and I had our own slideshow before sending our favorites to Kodak to be digitized.

I made Dad look through everything — 18 decades worth of possessions — to make sure he didn’t want anything. He never did.

You’d think one lesson here would be not to hold on so tightly to the material, but suffice it to say, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

My brothers and I keep too much, too. We are collectors — which left little room to house our parents’ stuff.

Tough calls had to be made. Old items found new owners. I knew Mom would be pleased that her possessions were finding good homes.

(Things that didn’t land with family or friends were sold online or at yard sales — I had three. There were also multiple trips to Goodwill.)

With age, the gift of time is the most precious

I learned that when parents tell us they don’t want gifts, they mean it. What they want and need is our time.

Nineteen months after Mom died, she and Dad were reunited.

My parents’ generation looks at mine and asks, “Why don’t you want this?” Just as my children’s generation asks, “Why are you keeping that?” Both have a point.

When I look around my house, I realize my children won’t want much of what I have, so the only reason to keep anything is if I use it or it gives me pleasure.

We all know “we can’t take anything with us,” but my parents’ deaths drove that point home.

What we can do is declutter the space that is ours and cherish the limited time we have with our loved ones.

Instead of collecting things and stuff, we can collect relationships.

My parents’ few remaining friends have become more precious to me since my parents’ deaths. I’ve had a dinner party for several, taken knitting lessons from one, and helped our family's Santa sort through his piles when they've gotten too high. I've also become penpals with one of Mom's best friends, who wrote, “As long as I have you, I still have Ann.”

Those friends are all in their 90s and won't live forever, just as I won't. But our relationships with loved ones live on in our hearts and memories.

In November, I spent a good part of 10 days in my parents' home, cleaning, repairing, and painting in preparation for new tenants. Even though every drawer, cabinet, cupboard, closet, and room was devoid of all the stuff that once lived there, my heart was filled with love, and my mind danced with memories.

Janet Meckstroth Alessi has been teaching at John I. Leonard High School since 1983 and is a frequent contributor to Accent. She can be reached at jlmalessi@aol.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Janet Alessi on the bittersweet job of clearing out her parents' home