Federal police accountability 'nearly impossible' in New England after Supreme Court case

Attorneys and civil rights advocates fear a new U.S. Supreme Court ruling will make it harder for people to sue federal law enforcement agents who violate their rights during warrantless searches.

On June 8, the court ruled against a man who had sued a U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent for excessive force, allegedly violating his Fourth and First Amendment rights.

Now, advocates say they worry, based on past Supreme Court cases, the 6-3 decision could be broadly applied to all federal agencies, not just border agents.

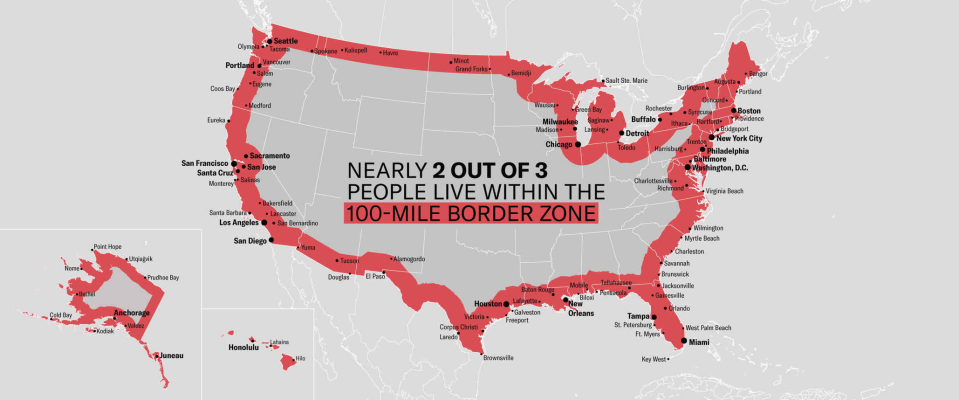

That could mean federal agents are protected from those lawsuits in nearly all of New England because the court has already held the Fourth Amendment doesn’t fully protect people against unreasonable searches and seizures within 100 miles of an international border or coastline.

Save for a southern chunk of Vermont and a small corner of northwestern Massachusetts, all of New England lies within the so-called 100-mile border enforcement zone due to the proximity to Canada and the Atlantic Ocean. About 210 million people — about two-thirds of the United States’ population — live within the zone nationwide, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

“This case really has made it nearly impossible to hold (federal officials) accountable when there’s a Fourth Amendment violation or other constitutional violations,” said ACLU of Maine Legal Director Carol Garvan.

More lawsuits: A mistake sent an asylum seeker to El Salvador. Then he was tortured, a lawsuit claims

The Fourth Amendment protects people from unreasonable search and seizure by police and other government representatives. Typically, local and state law enforcement officers must obtain a warrant signed by a judge before conducting searches.

Attorneys and advocates are also concerned about the racial implications of the Supreme Court's June 8 ruling because of the disproportionate number of civil rights violations involving people of color in lawsuits against law enforcement officials at all levels.

"I do think that will be made worse by this ruling,” said Garvan.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection is the largest federal police agency in the country and employs nearly 20,000 agents. It, along with other immigration and national security agencies, has a track record of racial discrimination, according to a two-year investigation by Georgetown University Law Center.

What the Supreme Court's border enforcement ruling does and doesn't do

The Supreme Court ruled June 8 against a man who had sued a U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent for excessive force near Washington's border with Canada. The 6-3 decision in Egbert v. Boule blocked the man’s attempts to hold federal agents accountable for allegedly violating his Fourth and First Amendment rights.

The decision doesn’t alter federal agents’ unique authority within the 100-mile border enforcement zone, nor does it gut Fourth Amendment protections.

Instead, Egbert narrows the options American citizens have to hold federal agents accountable for their actions, according to legal experts who spoke to the USA TODAY Network.

Customs and Border Protection, Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services employees are authorized under 8 U.S. Code § 1357 to “board and search for aliens” without a warrant on any “railway car, aircraft, conveyance, or vehicle” within the 100-mile zone.

The law also allows border patrol to go onto private land, but not homes, within 25 miles of the border “for the purpose of patrolling the border to prevent the illegal entry of aliens into the United States.”

America is still trying to figure out how to frame the journey of descendants of its enslaved

Americans may file civil rights lawsuits against state and local police under a Reconstruction-era federal law, but that law doesn’t apply to federal law enforcement. Claims against federal agencies are instead allowed under a Supreme Court precedent from 1971.

Lower courts have been divided since then on whether suits should be allowed against federal police in national security matters such as border patrols, among other circumstances. The debate bears similarities to debates surrounding qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that protects local police officers from liability for civil rights violations in many circumstances.

Vermont wants to ban qualified immunity: Success in other New England states is lacking.

Under Egbert, federal agents would now be similarly immune unless the circumstances of the alleged violations in the 100-mile border zone match those of previously heard cases, Garvan argued.

“Unless your claim you’re bringing now is just like one of those previous cases, then you’re out of luck,” said the ACLU of Maine legal director.

What the Supreme Court justices wrote about protecting federal agents against civil rights suits

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the 6-3 majority in the June 8 Egbert ruling, said Congress is better equipped than federal courts to authorize unreasonable search and seizure lawsuits against government employees.

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch agreed in a concurring opinion.

"Weighing the costs and benefits of new laws is the bread and butter of legislative committees," Gorsuch wrote. "It has no place in federal courts charged with deciding cases and controversies under existing law.”

Legal experts who spoke to the USA TODAY Network said this is a stark change in outlook for a court system that typically hasn't consulted with Congress before ordering damages against federal officials for rights violations.

Supreme Court Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor voiced similar concerns in a dissenting opinion on June 8. She wrote the court’s “drive-by, categorical assertion” in Egbert “closes the door” to lawsuits and "absolutely immunize(s)" border agents from liability no matter how egregious the misconduct or injury.

Maine keeps ruling shootings as justified:Experts point to one needed reform.

“This is no hypothetical: Certain (Customs and Border Protection) agents exercise broad authority to make warrantless arrests and search vehicles up to 100 miles away from the border," Sotomayor wrote. "The Court’s choice to foreclose liability for constitutional violations that occur in the course of such activities, based on even the most tenuous and hypothetical connection to the border (and thereby, to the ‘national security context’), betrays the context-specific nature of Bivens and shrinks Bivens in the core Fourth Amendment law enforcement sphere where it is needed most.”

The case Sotomayor referenced in her dissenting opinion, Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, is the 1971 federal case that authorized lawsuits against federal agents.

Federal accountability's 'death by 1,000 cuts'

Court watchers across the country described the Egbert decision as the latest progression in efforts to undermine remedies for constitutional abuses.

Patrick Jaicomo, constitutional litigator at the libertarian Institute for Justice, tweeted “courts don't need a permission slip from Congress to enforce the constitution."

Big picture, Egbert is the latest in the Court's death-by-1000-cuts approach to klling Bivens (w/o having to confront stare decisis or public outrage). What Egbert holds is that federal police *involved in immigration related functions* (about half) now have #FederalImmunity. 3/ pic.twitter.com/MbPLqHqs0W

— Patrick Jaicomo (@pjaicomo) June 10, 2022

"Big picture, Egbert is the latest in the Court's death-by-1000-cuts approach to klling (sic) Bivens (w/o having to confront stare decisis or public outrage),” Jaicomo tweeted in a June 10 thread. "What Egbert holds is that federal police *involved in immigration related functions* (about half) now have #FederalImmunity."

Carl Takei, senior staff attorney at the ACLU, tweeted Egbert is "a lawless, dangerous decision that makes the Bill of Rights a dead letter."

In plain words, the SCOTUS decision today in Egbert v. Boule immunizes border agents from liability for violating the Constitution. It also foreshadows similar immunity for all federal agents. This is a lawless, dangerous decision that makes the Bill of Rights a dead letter. /1

— Carl Takei (@carltakei) June 8, 2022

Gorsuch acknowledged how Egbert protects federal officials from legal liability in the concurring opinion he wrote in the case.

“In fairness to future litigants and our lower court colleagues, we should not hold out that kind of false hope, and in the process invite still more 'protracted litigation destined to yield nothing,’” Gorsuch wrote.

Jaicomo and Institute for Justice colleague Anya Bidwell panned Gorsuch in a USA TODAY column. Why, they asked rhetorically, pretend a remedy “still exists?”

“The Supreme Court should return to its historical and constitutionally required practice of doing law and ensuring ‘that every right, when withheld, must have a remedy, and every injury its proper redress,’” they wrote. “Public interest lawyers, like those at the Institute for Justice, will continue bringing cases to the Supreme Court to urge it to do so. But if it refuses to live up to its constitutional obligations, the court should at least have the courage of its own convictions and say federal officials can never be sued for violations of constitutional rights.”

New England ACLU chapters challenging border enforcement

ACLU’s affiliates in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont have sued Customs and Border Protection over checkpoints they’ve conducted within the 100-mile border zone.

If judges issue bad rulings and people die, should the courts pass the disciplinary gavel?

The suit, filed in New Hampshire in 2020, claims border agents have engaged in racial profiling to detain hundreds or possibly thousands of people during peak tourism seasons “without any suspicion that they have committed a crime.” It seeks changes to Border Patrol practices that could protect constitutional rights.

Even if the suit is successful in enacting changes, Garvan, the ACLU of Maine legal director, said the public should take the Supreme Court’s advice in Egbert and call on their elected officials to create defined legal remedies when a court denies a Bivens claim.

“Hopefully (increased awareness can) make people understand this is something to advocate for to their representatives so we can have a hope of Congress creating a cause of action there,” said Garvan.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: New England affected by Supreme Court case of police accountability