The FBI’s Persecution of Sidney Poitier

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

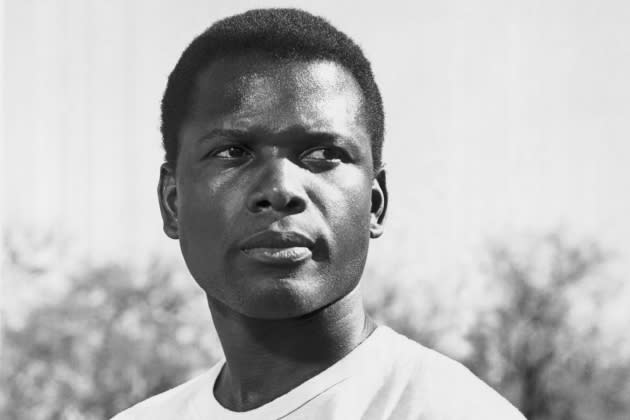

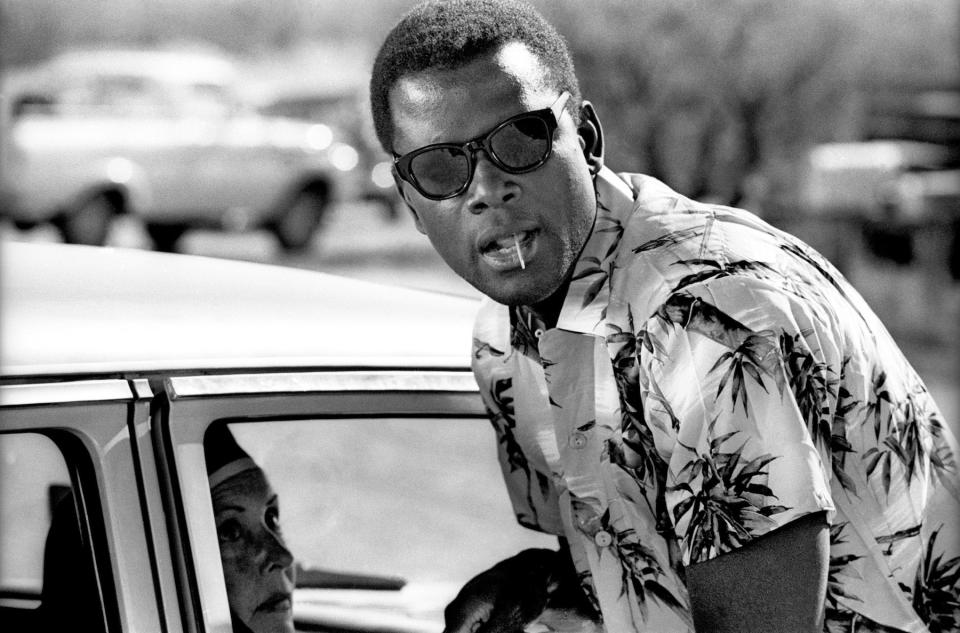

Sidney Poitier walked among kings and earned Hollywood’s highest honors, but that didn’t stop the Federal Bureau of Investigation from keeping tabs on the actor and philanthropist via informants and surveillance tactics during the civil rights era, according to documents newly obtained by Rolling Stone. Poitier, who passed away at age 94 on January 6, 2022, had a career that lasted 75 years and was surveilled by the agency at the height of his fame.

Poitier’s FBI file – requested via the Freedom of Information Act – is 13 pages long, covering 1959 to 1963, with some pages newly declassified in 2023 following Rolling Stone’s request. The documents, which are labeled Part 01, almost certainly don’t include everything the agency collected on the man who was the first Black performer to win an Academy Award for Best Actor. Yet its contents reveal an era that had the agency tracking the actor much in the way they did Aretha Franklin, as first reported by Rolling Stone.

More from Rolling Stone

James Bond Novels to Be Reprinted With Racist Language Removed

Beyond 'The Last of Us': Three Video Game Maestros Reveal Their Secrets

'The Quiet Girl' Is One of the Most Heartbreaking Movies in Ages

Focused largely on Poitier’s associations with civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., efforts to raise funds for underprivileged Black youth, pushes toward integration, and support of organizations like the NAACP and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the FBI files have many redactions and notably contain submissions by informants who had infiltrated the organizing efforts of civil rights groups.

Oscar-winning actress – famously blacklisted for 12 years by the House Un-American Activities Committee – and documentarian Lee Grant, who starred with her longtime friend Poitier in In the Heat of the Night and went on to create the PBS documentary Sidney Poitier: One Bright Light with the actor about his life, told Rolling Stone, “He didn’t come from that place of having a foot put on your neck. He came from the beach. He came from a joyous place. He was Sid-nerella,” comparing Poitier’s unassuming beginnings to the life he’d go on to live.

Grant is referring to Poitier’s childhood, which is itself cinematic. He was a Bahamian born three months prematurely in Miami, Florida, in 1927. His mother and father had been briefly in the U.S. to sell tomatoes grown on their farm in Cat Island, Bahamas. Baby Sidney wasn’t expected to survive, but his mother refused to accept that outcome and visited a soothsayer, who told her, “Don’t worry about your son. He will survive, and he will not be a sickly child… he will travel to most of the corners of the earth. He will walk with kings. He will be rich and famous. Your name will be carried all over the world. You must not worry about that child.”

He was healthy, and at age 15, he left the majority-Black Cat Island and Nassau, Bahamas, to return to his accidental birthplace of Miami. Living with his older brother, Poitier explained in Grant’s documentary that this move would be the first time he experienced racism. Away from a simple life he describes almost blissfully, he took a job as a delivery boy. He didn’t know he was supposed to feel inferior based on American society’s backward rules and delivered a package to a white woman at her front door instead of the back. Returning home to his strangely unlit brother’s house later in the night, his sister-in-law pulled him in, distressed, and demanded to know, “What did you do?” The Ku Klux Klan had visited with threats because of his “incorrect” place of delivery. Scared, Poitier took off to New York City, where he’d heard there was a vibrant Black community.

With limited education and a newfound desire to become an actor based on a classified ad he saw in a New York paper, Sidney was taught to read by a Jewish man who’d seen him struggling to do so. Lee Grant explains, “He just broke the color barrier all by himself, not knowing it and not accepting it… It’s like a Dickens story: you plop him down in another world, and he says, ‘Fuck that, I’m going to the big city.’”

Despite his passion for acting, Poitier found relatively few acting opportunities were open to him early on because of his skin color, and suffered many indignities as a man and actor over time. When working in South Africa on Cry, the Beloved Country in 1951, Poitier had to sign a paper making him the director’s indentured servant so he could legally work in the country. Separately, back home, he and others tried to raise the question of more employment opportunities for Black actors by petitioning the Actors’ Equity Association. Poitier would later say that “those of us who petitioned wound up being blacklisted. I was one of the young Black actors who became persona non grata, charged with being a troublemaker.”

In Grant’s Poitier documentary, he expanded on his involvement with activism due to his experiences, saying, “The law said, in America, you will be treated as less-than. I could never adjust to that. So, I became involved in the civil rights movement.”

The FBI took note of his movements working for justice. In 1959, the agency collected a news clipping titled, “Sidney Poitier Joins as Co-Chairman in Youth March for Integration.” In the article, Poitier said the campaign “may very well mark a turning point in the struggle for freedom of all Americans.” The event cited in the article was held on April 18, 1959, and included attendees such as Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King Jr.

An FBI document from 1960, which was declassified on January 4, 2023, shows that a repeat informant “advised that literature from the African-American Students Foundation, Inc.” was “probably getting wide dissemination in the U.S.” and may have used NAACP lists, of which Sidney Poitier was a member. The same document shows that a second and third informant were also used in gathering information and that “[REDACTED] has been advised to immediately advise [the FBI] of any additional data received concerning the African-American Students Foundation, Inc.” The second page remains heavily redacted.

In 1960, a document declassified on January 18, 2023, following Rolling Stone’s request, showcases the FBI’s use of three confidential informants, again regarding the African-American Students Foundation, Inc. and its movements to grant scholarships to young men and women from Kenya. Jackie Robinson and Sidney Poitier are signatories on a letter copied to the document where they personally pledge to donate money for the Kenyan students. The document notes that “Jackie Robinson, former major league baseball player and Sidney Poitier, actor, are prominent American Negroes, who are outspoken advocates of racial equality.”

Poitier biographer Aram Goudsouzian points out that the actor “helped fund the program along with Jackie Robinson and Harry Belafonte, providing university scholarships to Kenyan students. Institutions like the British Embassy and the U.S. State Department feared that these students would stir anti-American sentiment and cause racial unrest. Fascinatingly, the program allowed for a Kenyan named Barack Obama to attend the University of Hawaii, where he met Ann Dunham. In 1961, they sired the future president of the United States.” In 2009, then-President Obama presented Poitier with the Congressional Medal of Freedom.

Before Poitier made history by winning the Oscar for Best Actor for Lilies of the Field in 1964, a 1963 FBI document took note of a Washington, D.C. screening of the movie for the benefit of the NAACP, Congress for Racial Equality, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, noting that the screening was to raise funds for “the furtherance of the programs of these organizations.” This was, apparently, notable enough for the agency that they forwarded the information to the Metropolitan Police Department in D.C.

Despite the Poitier FBI files ending after just 13 pages, Rolling Stone reported previously on files we obtained on Aretha Franklin, which further revealed the extent of the agency’s surveillance of Poitier, including a document from 1967, declassified after our request in 2022, which is titled, “Communist Infiltration of Southern Christian Leadership Conference Internal Security,” noting, “Sidney Poitier, popular actor, will be the featured speaker at the opening banquet August 14, 1967…”

The FBI did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Retired FBI Special Agent Michael German, now a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, told Rolling Stone, “These documents, which are clearly not the totality of FBI records referencing Sidney Poitier, highlight the extent to which J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI monitored Black celebrities involved in social and racial justice issues. Hoover was an inveterate racist who considered any challenge to the existing white power structures as a threat to national security. Particularly, Hoover feared the rise of charismatic Black leaders who led the struggle for civil rights, and he directed his agents to monitor them and their organizations or, worse, to disrupt their lives with a toolbox full of dirty tricks. Anyone who has seen a Poitier film can confirm his charisma.”

There’s indication Poitier had at least some inkling he was under the watch of the FBI and more than an inkling about the threat of being blacklisted in other ways. In his book The Measure of a Man, he remarks that before production began on A Man Is Ten Feet Tall, he was called into NBC and asked to distance himself from musician and actor Paul Robeson, who was on the HUAC blacklist, and to sign a loyalty oath – the purpose of which remained unclear to Poitier.

Poitier wrote, “I went on to explain that I simply couldn’t do this… Yes, I was definitely, by then, inclined toward the left of center… I found more people like Phil Rose and David Susskind, people demonstrating a genuine willingness to receive me as an equal. This was reason enough, I suppose, for the FBI to keep an eye on me, given the fear and panic of those terrible cold war days of madness… Blacklist or no, I was determined that I was going to be an actor.”

After declining multiple requests to sign loyalty oaths, Poitier remained unsure as to why the matter was dropped.

That was the second time Poitier was asked to sign such an oath. While working on the movie Blackboard Jungle, also released in 1955, Poitier was called into the office by a studio lawyer who questioned his associations with the likes of HUAC-blacklisted Robeson and boxer Canada Lee. Recounting the tale, Poitier said, “It drove me wild that these men could see red but couldn’t see Black… I was being accused of being sympathetic toward, respectful of, even admiring of Paul Robeson and Canada Lee – men I did respect tremendously!… Here I am in a culture that denies me of my personhood… this land once declared me to be three-fifths of a human being, and that only one hundred years earlier the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court had declared people of my race to be, ‘so inferior, that they had no rights.’… every attempt I make to articulate myself as otherwise is met with resistance, and here this guy is saying to me, ‘we want you to swear your loyalty.’ To what, I wanted to know.”… There’s no way. He wants my soul… this is not something that’s for sale… and [Director] Richard Brooks looked me in the eye, and he said, ‘You know what? Fuck him.’ And we started shooting the picture.”

Longtime agent and friend Martin Baum said in a 1996 interview, “I saw the evidence of the blacklist that he was on. His crime being that he was a roommate of Canada Lee – a man that I admired greatly and that he admired greatly.”

Goudsouzian says of the blacklists of the time, “Black performers were under various forms of surveillance in the era of the early civil rights movement. There was no one “blacklist,” but rather various memos and communications that were meant to cast suspicion on Black celebrities who engaged in politics. (Various ‘graylists’ rather than one “‘blacklist.’ In 1957, the anti-communist newsletter Counterattack noted various political activities by Poitier.”

Of the FBI files on Poitier, German emphasizes, “Nothing in files suggest a hint of illegality, violence, or sedition, and the FBI had no business tracking Poitier’s First Amendment-protected activities with these groups, much less maintaining this material in its files. No American should ever have had to worry that a powerful government agency would monitor their non-violent political activism, or that it could secretly disrupt their livelihoods without due process.”

The Civil rights and Hollywood historian Emilie Raymond tells Rolling Stone, “Poitier’s, as well as [Martin Luther] King’s and [Harry] Belafonte’s, files and their connection to COINTELPRO should remind Americans that the FBI has a long track record of monitoring Americans for their supposed ‘extremism.’ But it’s the FBI itself who is defining and interpreting ‘extremism,’ so almost anyone can be swept into the agency’s radar.”

The FBI continues to raise alarms with its approach to modern civil rights groups and Black-led organizations. According to former FBI Special Agent German, “Not surprisingly, a new era of Black activist has come under scrutiny and the FBI has resurrected ‘disruption’ as a tactic. Sunlight is always the best disinfectant, so bringing these historical abuses to light is crucial to understanding how an agency with such an important mission as protecting the American people becomes a threat to them.”

Poitier was a man with many dimensions, and while his race was entwined with his experiences, he sometimes became frustrated with reporters for focusing on his race at the exclusion of everything else. In 1968, after being asked by reporters about civil unrest, he said pointedly, “I figured that question would come… I am, by definition, in opposition to violence. Particularly, violence for violence’s sake… I would like to ask you a question. Why is it that you guys are hounds for bad news?… You guys have a job to do. I’m a relatively intelligent man. There are many aspects to my personality that you can explore. I think very constructively. But you sit here and ask me such one-dimensional questions about a very tiny area of our lives. You ask me questions that fall continually within the Negro-ness of my life. You ask me questions that pertain to the narrow scope of the summer riots. I am artist, man, American, and contemporary. I am an awful lot of things, so I wish you would pay me the respect due and not simply ask me about those things.”

Hollywood continues to have its own issues with race to contend with. The 2023 Oscars are set to take place on March 12, and the Academy historically has a diversity problem, tending to undervalue Black performers. The first Black actor to be nominated for and win an Oscar was Hattie McDaniel in 1940 for her role as Mammy in Gone With the Wind. Notably, she was forced to sit at a segregated table away from her castmates and was barred from the afterparty. After McDaniel, another Black actor did not win until Sidney Poitier for his role as Homer Smith in Lilies of the Field, with the win coming 24 years later, in 1964. And another Black woman didn’t win an acting Oscar until Whoopi Goldberg a half-century after McDaniel for Ghost.

This year, two Black actresses, Viola Davis and Daniel Deadwyler, were widely expected to receive Best Actress nominations only to be snubbed. Of her snub this year for her role as Mamie Till-Mobley in Till, Deadwyler said on the Kermode & Mayo’s Take podcast that the lack of nomination was “misogynoir.” On Instagram, actress Viola Davis said of her snub for The Woman King, “Allyship = Active support for the rights of a marginalized group without being a member of it. THIS is what’s missing. Whether it be a ‘grassroots’ campaign spearheaded by peers or multi-million industry dollars backing one, we rarely are the benefactors.”

Hollywood has a way to go on equality, as does the country at large, but we have the legacy of the man who built a chapel for nuns in Lilies of the Field, showed America that love is love in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and slapped back with dignity in In the Heat of the Night to look to as a guiding light. Poitier broke down barriers he didn’t even know existed when he began his career. Lee Grant reminds us that Sidney Poitier, her dear friend, “Walked with kings, and he became one.”

Best of Rolling Stone